In 1933 a newspaper columnist described Otto Soglow as “a great cutup” who “clowns all over the place” at parties, livening up the scene with magic tricks and jokes. This convivial portrait of Soglow as a merry prankster is reinforced by the photos that adorn Jared Gardner’s introduction to the new collection Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow and The Little King. One photo shows Soglow cheerfully parading his legs in a mock all-male chorus line made up of members of the National Cartoonists Society. In another snapshot Soglow wears a broad grin as he displays the power of a waterproof pen by drawing his signature character the Little King on swimming trunks worn by a zaftig model.

Soglow clearly belonged to the tribe of tricksters, so it is entirely fitting that he earned a sly tribute from one of the great harlequins of literature, Vladimir Nabokov. In his memoir Speak, Memory (original edition 1951), the novelist describes his younger self surveying his early literary production: “The ranks of words I reviewed were again so glowing, with their puffed-out little chests and trim uniforms....” In a later edition to the book, Nabokov called attention to this sentence and rather kittenishly lamented that not one reviewer discovered that it contained “the name of a great cartoonist and a tribute to him.” To turn Soglow into “so glowing” is a bit of a strained pun but the sentence as a whole is a nifty encapsulation of the cartoonist’s work, which is rife with shimmering parades of soldiers and guards neatly arrayed in their dapper uniforms with their balloon-like little chests sticking out.

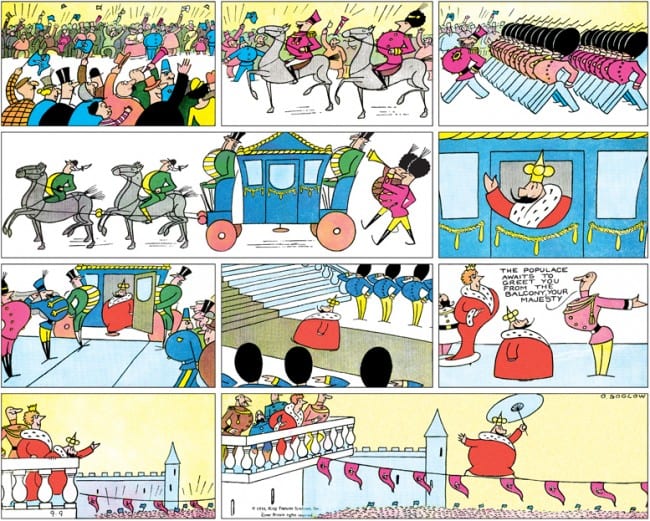

Nabokov’s tip-of-the-hat to Soglow offers a clue to the cartoonist’s appeal. Like the author of Lolita and Pale Fire, Soglow specialized in the comedy of the unexpected, the humor of surprise, the mirth of looking at the world from an unexpected angle. The Little King was a long-lived strip -- it started as a recurring feature in The New Yorker in 1930 and was syndicated in newspapers as a weekly feature from 1934 until Soglow’s death in 1975. Despite its longevity, The Little King relied on variations of one joke: the King is surrounded by courtiers and subjects who diligently obey the rules of high state which the sovereign playfully subverts.

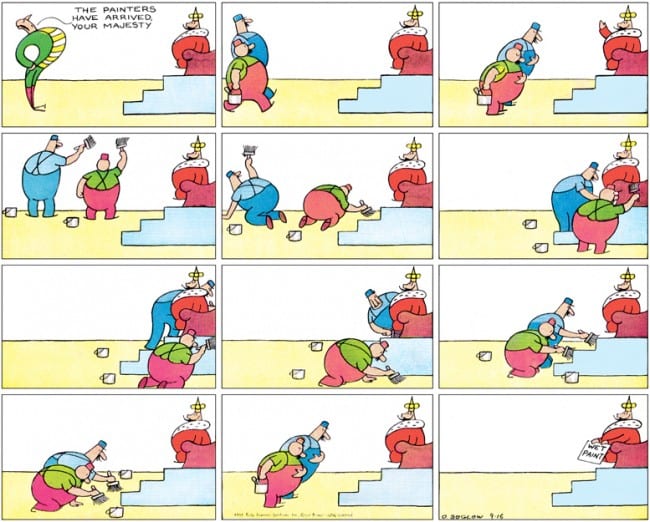

The Little King is the court jester in his own castle. Here is a rundown of the King’s actions in the first few strips: he uses a banner stretched out before his balcony as a tightrope; he holds up a wet paint sign after his throne room is painted; he parachutes off a plane while seated in his throne; he uses a cardboard cut-up of himself to take over the tedious job of watching soldiers march; he tries to calm his wailing princeling by having the butler push him and the baby in circles in a go-cart.

The essence of the carnival, Mikhail Bakhtin has taught us, involves turning the world upside-down, with kings are reduced to beggars and beggars are showered with gifts. In that sense, The Little King is a profoundly carnivalesque strip.

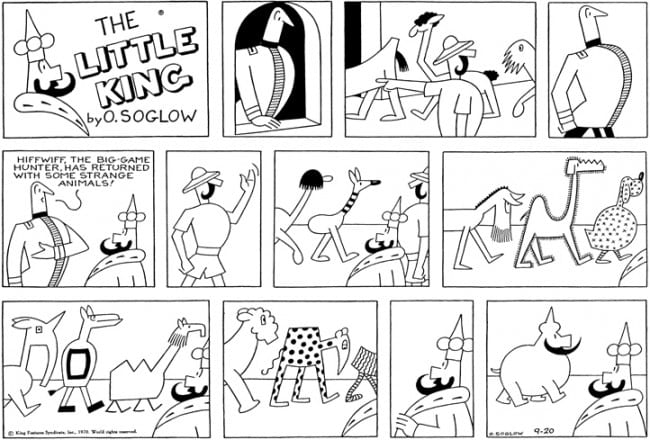

These strips set the tone for the entire run of The Little King. Occasionally Soglow will make a nod in the direction of the daily news, as in 1940 when he introduced Ookle the Dictator, a recurring character for the next few years or in the post-war strips about UFOs. But such topical strips are the exception and Soglow’s focus rarely shifts from the central comedy of the Little King’s carnivalesque upturning of the social order. Soglow’s monarch is a very democratic ruler, a problem-solver with a talent for finding unconventional solutions, a lord who is not afraid of getting his hands dirty and indeed consorts with such lowly subjects as hobos and sewer workers.

The gleeful mood of the strip would be impossible without Soglow’s art. As Ivan Brunetti notes in his sharp foreword to this book, “The Little King wouldn’t be funny unless there was some sense that dignity and decorum exist within the strip’s universe. The sleek and concentrated drawing creates a background of rigidity, rules, convention, and correctness, which the titular character impishly circumvents and happily, without malice, violates.”

The puffed-out chests that Nabokov called attention to are a clue as to the way Soglow’s drawings create a clash between hide-bound propriety and irrepressible mischief-making. The puffed-out chests all belong to courtiers, soldiers, guards, and other figures who have their noses in the air as they carry out their appointed rounds. The monarch that they serve, by contrast, is a much earthier figure with his beach-ball belly hanging low to the ground. Since we always see him in profile, the Little King is very close to being a playing-card monarch (and indeed in one strip serves as a model for a playing card). He’s a marvel of character design, with his jutting half-rectangular nose, canoe-shaped beard, and emblematic crown (a triangle and three circles: a nice example of Soglow’s tendency to reduce images to Euclidian geometric purity).

Otto Soglow was one of the major stylists in the history of comics. Along with a handful of other artist — Hergé, Gluyas Williams, Rea Irvin — he was a central instigator in the stylistic revolution of the late 1920s and early 1930s that created the clear line style. Of course, early Art Deco-influenced cartoonists like George McManus had laid the groundwork for the clear line, but Soglow and his contemporaries purged Deco of any ornamentalism and developed a cartooning language that united elegance with minimal but forceful line work.

One of the great strengths of Cartoon Monarch is that it gives us a very generous sample of Soglow’s work from many facets of his career so that we can see that the clear line style was a hard won victory for the cartoonist. Rather surprisingly, Soglow started off as a student of such Ash Can School masters as Robert Henri, George Luks, and John French Sloan. Like them, he specialized in charcoal-dark representations of urban squalor (some of which appeared in radical publications like The New Masses).

Soglow’s move to the clear line wasn’t a complete break from his earlier art since he continued to do anecdotal art about urban life, but his art started to become more line-focused and less shadowy as he became a fixture in The New Yorker, where the Little King first appeared in 1930. I’d speculate that Rea Irwin was an influence. Contractual wrangling with the New Yorker seems to have prevented Soglow from immediately moving the monarch to newspapers when the Hearst Syndicate hired him in 1933. As a stop-gap measure, Soglow created The Ambassador, who was the Little King in everything except title and facial features (the Ambassador had a bulbous nose and a walrus moustache).

Cartoon Monarch gives us samples of Soglow in his various styles and modes: as a young radical doing proletarian realism, as a cosmopolitan New Yorker artist, as the fixture of mid-century American book illustration and advertising, and finally as the celebrated comic strip maestro behind The Little King (with The Ambassador as an appetizer and a top strip called Sentinel Louis as desert). Deceptively simple as Soglow’s art might seem, the book makes clear how hard he worked to achieve his distilled style. The Ambassador and the early Little King strips even look a little cluttered and bloated compared to the pared down, rapier sharp cartooning that Soglow achieved in his peak years (which to my eyes ran from the late 1930s to the early 1960s).

To create a style where every line counts, where nothing is included in the picture plane that doesn’t need to be there, where words only show up when absolutely necessary while pictures do the heavy lifting of carrying the narrative: that’s what Soglow achieved in The Little King. It’s a legacy that continues to inform the work of many our best cartoonists – notably the aforementioned Brunetti but also Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, Mark Newgarden, and Richard McGuire.

Cartoon Monarch is in every way a topnotch book: elegantly designed, offering a satisfying tour of Soglow’s long and complex career, adorned with a smart foreword and an eye-opening introduction. Gardner’s essay on Soglow expertly links the biography to the art, and is rich in insight. My only complaint is that it doesn’t give much of a sense of Soglow’s private life, but I suspect that the reason for this is the dearth of sources.

It’s now a cliché to say that we’re living in the golden age of comics reprints. That’s true enough, and many of us are so spoiled that we might take a book like Cartoon Monarch for granted. But the further point needs to be made that the most valuable books in this golden age aren’t the ones that give us more complete editions of the masters we’re already familiar with. Those books are important but they don’t change how we see history. The really crucial books are the ones that recover the cartoonists who have been nearly forgotten or are remembered hazily. I’m thinking here of Dean Mullaney’s earlier book on Jack Kent (with Bruce Canwell’s fine introduction), or the Denys Wortman collection edited by James Sturm and Brandon Elston, or Paul Karasik’s books on Fletcher Hanks. Such recoveries and excavations imperfectly appreciated cartoonists force us to redraw our mental maps of comics history.

Otto Soglow was one of the central cartoonists of mid-century America. He’s never been completely forgotten. Any roll call of the major New Yorker cartoonists usually includes his name and most history of comic strips allot a paragraph or two to The Little King. Still, until this book it was hard to get a handle on why Soglow was so important. With Cartoon Monarch, we can finally begin to gauge his achievement.