In his autobiography, Stravinsky wrote about the importance of observing the movements of the players while listening to a composition, avowing that the “fullness” of the music could only be comprehended through witnessing its performance. It’s an unfit metaphor for comics, which aren’t thought of as a “performed” art, but in her new book of collaged stories, Carpet Sweeper Tales, Julie Doucet asks that we read the book’s dialogue out loud; in addition to looking at pictures and reading words, she insists we add voice.

The trouble is that the dialogue is nonsense: “Drape is aise free,” a man says, to which his companion replies, “Aft arns kind ine tic.” Doucet snipped the books’ pictures from sixties Italian fumetti, but these otherwise straightforward photographic images of men and women (they could just as easily be stills from Days of Our Lives) take on a perplexing, and sometimes sinister, hue when paired with the graphemes Doucet cleaved from American domestic magazines. The experience is a bit like taking in a foreign film without subtitles. And reading the dialogue aloud feels at first like speaking in tongues. But the glossolalia passes when the reader endows the sounds with emphasis using the images as cues—a process that wouldn’t take place if Doucet hadn’t instructed us to voice the dialogue. It you don’t read it aloud, it won’t come to life.

It’s fun to try to make sense out of the nonsense. The energized sentences that result are unique to each reader, their sounds and meanings derived in part from our own individual experiences with language. Doucet doesn’t explicitly tell us what to think about her characters, requiring instead that we be active readers. The stories imagine conflicted relationships between men and women. Action is minimal at best, and most frequently the situations resemble those of soap operas, in which pairs or small groups of people converse and stalk around. Tone, then, is hinted at in the way characters look at, away from, or past one another. It comes, too, in Doucet’s skillful and subtle choices of font: uppercase, lowercase, italic, and underline but also punctuation and glyphs.  In one story, a blonde named Mrs. Jones seeks counsel from a nun. “YOU CAN EAD for CHR THO KS far better VIRTUE BRAS,” the nun advises. In the next panel, Mrs. Jones slumps forward, her face slack and unhappy. “Virtue ME BOO OVER. ME this be,” she complains. Doucet has chosen an italic cursive for Mrs. Jones’s use of virtue, and it serves to accentuate the word, suggesting that Mrs. Jones, who is repeating the nun’s use of the word, pronounces it acidly. The nun, who stands behind her, then replies, “you needn’t be ch R”—and “needn’t be ch” is also set in an italic cursive so that her tone is chastising.

In one story, a blonde named Mrs. Jones seeks counsel from a nun. “YOU CAN EAD for CHR THO KS far better VIRTUE BRAS,” the nun advises. In the next panel, Mrs. Jones slumps forward, her face slack and unhappy. “Virtue ME BOO OVER. ME this be,” she complains. Doucet has chosen an italic cursive for Mrs. Jones’s use of virtue, and it serves to accentuate the word, suggesting that Mrs. Jones, who is repeating the nun’s use of the word, pronounces it acidly. The nun, who stands behind her, then replies, “you needn’t be ch R”—and “needn’t be ch” is also set in an italic cursive so that her tone is chastising.

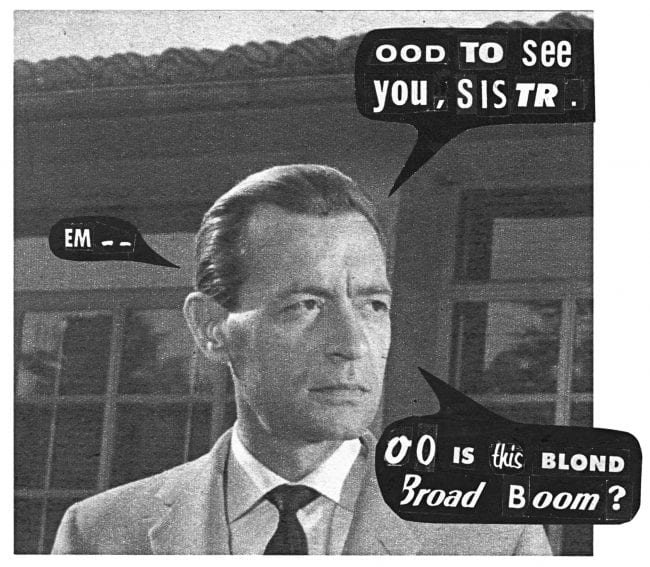

When a man, named Buick, enters the scene, Doucet conveys immediate tension between Buick and the nun. “OOD to see you, sistr,” Buick says, pinching the words good and sister. His face is a mask, and his greeting is displayed in a dispassionate, blocky san-serif. Yet when he inquires after Mrs. Jones—“OO is this BLOND Broad Boom?”—Doucet mixes roman and italic, upper and lowercase type, as well as suggestive alliteration, to indicate his ardent interest. The nun, however, responds disapprovingly: “Mrs. JONES IS OO,” she says unsmilingly, her words rendered in very vertical uppercase letters, with the “OO” in heavy, commanding type; her tone is clarion. For her part, Mrs. Jones is intrigued by Buick. Up to this point in the conversation, her only response has been to stare at him and emit a typographic ornament that resembles a coiled spring, sometimes with exclamation marks. She is speechless but clearly intrigued; “BR,” she finally mumbles.

When a man, named Buick, enters the scene, Doucet conveys immediate tension between Buick and the nun. “OOD to see you, sistr,” Buick says, pinching the words good and sister. His face is a mask, and his greeting is displayed in a dispassionate, blocky san-serif. Yet when he inquires after Mrs. Jones—“OO is this BLOND Broad Boom?”—Doucet mixes roman and italic, upper and lowercase type, as well as suggestive alliteration, to indicate his ardent interest. The nun, however, responds disapprovingly: “Mrs. JONES IS OO,” she says unsmilingly, her words rendered in very vertical uppercase letters, with the “OO” in heavy, commanding type; her tone is clarion. For her part, Mrs. Jones is intrigued by Buick. Up to this point in the conversation, her only response has been to stare at him and emit a typographic ornament that resembles a coiled spring, sometimes with exclamation marks. She is speechless but clearly intrigued; “BR,” she finally mumbles.

Just as many of the panels shift back and forth between the same faces—both within and between stories—so, too, does the dialogue frequently rely on patterns of sound: “Co co cou co cool cold” and “Duco cou you co” and “so do me boo too.” Some longer examples achieve a musicality: “of of of to to to or so for with with a that’s they you to to when” and “in a in an at at at” and “make m making s – make it / make m making s – to make free.” A near-wordless five-page story midway through the book experiments with rhythm by replacing alphabetic sounds with pure punctuation. On the opening page are the words “Better Quicker”—instructions, perhaps, considering that what follows are patterns of single and double quotation marks (some of which may be commas or apostrophes) and ellipses. Together, the marks constitute a kind of beat. In the first panel, a man looks intently at the woman sitting next to him in a car, while she looks away from him. Neither has opened their mouths to speak, so the pattern of marks in the two speech balloons could be the sound of their breathing. In the remaining four panels, the man and woman, and then the man alone, are smiling broadly and openmouthed; the corresponding marks seem to describe the cadence of their laughter.

With the exception of the opening page in this story, each panel also features a caption that contains long lines of single and double quote marks. These lines don’t contain additional typography (no exclamation points, for instance) and so appear comparatively dispassionate. The marks are also smaller than those of the balloons and are fairly uniform in size. Their staccato sequencing resembles Morse code, and like Morse code, which allows for the transmission of meaning through both visual and audible means, these tick marks are visual (marks on a page) and auditory (representing a beat or rhythm). In fact, all of Doucet’s language in this book enacts some form of transformation: between image (words in a magazine), text (bits of written dialogue), and speech (dialogue read aloud). In other cases, as with the punctuation, the visual becomes auditory as a system of marks, like musical notation.

Doucet’s fragmented and reconstituted sound-language echoes Kurt Schwitter’s Dada “sound-poems” and the zaum, or transrational poetry, of Russian Futurist Aleksei Kruchenykh. Both Schwitter and Kruchenykh abstracted words in order to liberate language from meaning: their letterforms are descriptive rather than prescriptive. In Schwitter’s “Ursonate,” which roughly translates to “sonata in primordial sounds,” the four movements are interspersed with a coda that comprises the German alphabet read backward; each of the three iterations is meant to be read aloud with a different pitch and tempo. Much of the poem relies on the repetition of sounds—“Lanke trr gll / Ziiuu lenn trll? / Lümpff tümpff trll.” Kruchenykh’s “Hum of Hillclimbing Locomotive” is a collection of sounds that approximate not just the noise of a train engine but also, importantly, its laboring momentum: “boro / choro / two / one / hubb / sham / ga / gish! / boro sorko ba.” In the same way, Doucet’s collection of sounds and patterns isn’t an unruly mess: she harnesses the constructed ejections and exclamations together, and they accrue a syntax.

The handmade, low-fi quality of the book—bits of cutout paper welded together, the pulpy newsprint on which it is printed—is sympathetic to the title’s reference to a manual mechanism that has been superseded by a more technologically advanced version, the vacuum cleaner. That notion of irrelevance plays out in the stories in the various ways men behave toward women. In one story, a man pursues a woman’s affections; she demurs, uncertain of his proposal. “I am Dust-Resistance for you. Me Clean ‘Magic’ carpet love,” he purrs. “When a woman Carpet Sweeper,” she sighs, trailing off. And later (and elsewhere in the book), she exclaims, “Ford you sweepmaster!” In the language of domesticity and commodities Doucet employs, this becomes an ultimate statement: a man can be a sweepmaster, but women regularly are made to feel like carpet sweepers. (The phrase carpet sweeper and its shabby connotations reminds me of Bashmachkin, the bullied clerk of Gogol’s “The Overcoat,” whose name means “carpet slipper.”)

Doucet’s decision to forego semantics clears the way for a fresh kind of meaning. Words relating to women are singled out and shown up as complex terms that bear a range of meanings, depending on the context and the speaker. A sequence in the latter half of the book follows a group of leather jacketed men who are so overcome by womanhood that they stutter over and again through the words girls, dolls, females, and maids. This is followed by a sequence in which a similar-looking group of men engage in what appears to be a thoughtful conversation using only the language of women’s sanitary products: feminine napkins, Tampax, Kotex, Carefree, Modess. Finally, in a third sequence, the men encircle a lone woman and harangue her with caveman-like stutters of baby, girls, woman, and mouse; she cowers before finally confronting them and declaring, “stop it you apes me no banana,” a comparatively eloquent statement that is met by a chorus of question marks.

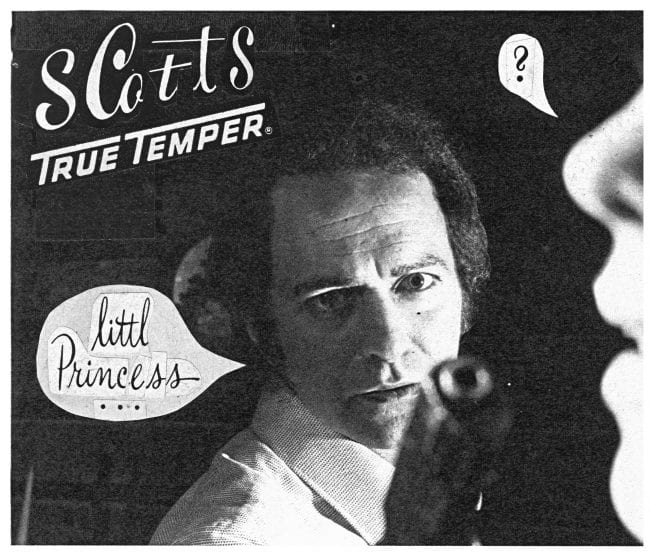

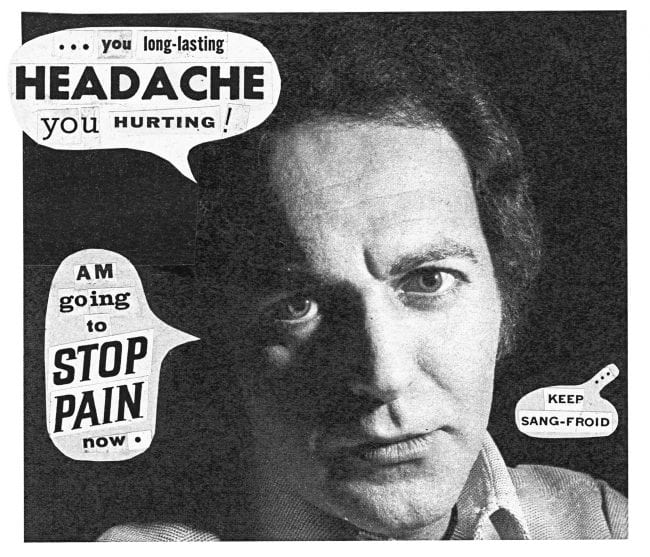

Doucet has called these “lightheartedly absurd stories” and says that she had nothing “special to tell.” And yet the book’s most well-turned story, “Scott’s True Temper,” concerns abuse, self-defense, and empowerment using borrowed terms from analgesic ads. As the story opens, the titular character is menacing a woman. “Littl Princess…,” he says, pointing a gun at her, “you long-lasting HEADACHE you HURTING! Am going to STOP PAIN now.” “Keep sang-froid,” she warns meekly, in a sort of small-cap lettering. Over the next two panels, he batters her. Suddenly, she blocks his fist with a cry of “KUKLA-OLLIE!” Control is now hers. In the penultimate panel, he reaches across the floor for his gun; “Cinderella… YOU NEURALGIA!!!” he sneers slangily. She stands over him, only her legs in view: “Me am no sleeping beauty,” she declares, passive no more. “Migraine!” he peeps, his headache from the opening not only worsened but now recursive.

Doucet has called these “lightheartedly absurd stories” and says that she had nothing “special to tell.” And yet the book’s most well-turned story, “Scott’s True Temper,” concerns abuse, self-defense, and empowerment using borrowed terms from analgesic ads. As the story opens, the titular character is menacing a woman. “Littl Princess…,” he says, pointing a gun at her, “you long-lasting HEADACHE you HURTING! Am going to STOP PAIN now.” “Keep sang-froid,” she warns meekly, in a sort of small-cap lettering. Over the next two panels, he batters her. Suddenly, she blocks his fist with a cry of “KUKLA-OLLIE!” Control is now hers. In the penultimate panel, he reaches across the floor for his gun; “Cinderella… YOU NEURALGIA!!!” he sneers slangily. She stands over him, only her legs in view: “Me am no sleeping beauty,” she declares, passive no more. “Migraine!” he peeps, his headache from the opening not only worsened but now recursive.

Carpet Sweeper is an exceptional book. Though Doucet stopped drawing comics more than a decade ago, these collages function as comics in the best possible sense: images and text so reliant on each other that one cannot operate fully without the other; and out of that interworking, narrative is born. Amid a kind of stuttering bewilderment, Doucet’s stories make sense. “I have always had a horror of listening to music with my eyes shut, with nothing for them to do,” Stravinsky wrote. Thankfully, Doucet has given the reader much to do.