Gilbert Hernandez nails his title character's emotional essence in the very first panel of Bumperhead, the prolific cartoonist's hormonally overdriven anatomy of adolescence. Fatefully named and thoroughly pissed off, a preadolescent Bobby Numbly stares defiantly at the reader as childish taunts – "There's a bump bump bumperhead here! Thumpin' bumpin' bumper! El Bumpo!" – join background clouds in a perfectly weighted composition filling two-thirds of the page. His tormentors are a couple of neighborhood boys in Oxnard, California – Los Bros Hernandez's own hometown. Presumably less "semi-autobiographical" than last year's bittersweet Marble Season, Bumperhead looks at sex, drugs, and rock with as much knowing sympathy as its predecessor explored childhood mysteries, obsessions, friendships, and disappointments.

While the Urban Dictionary defines "bumper head" as "A person who copies everything they see others doing," Bobby's damage is apparently the shape of his noggin, which, I gotta say, doesn't look markedly larger than any other illustrated Oxnardian drawn in Hernandez's form of cartoony naturalism. (As opposed to, say, his new Fatima series, which is about blood-geysering heads and little else.) But that's just one minor oddity in a book that punctuates a remarkably accurate portrait of a certain type of adolescence with much larger disturbances of the field. The most prominent of these is the "iPad" Bobby's best friend uses to see into the future. "Now when evil men die, we'll get to see it!" enthuses Lalo. The device neatly allegorizes Beto's omniscient authority. The "spaceship lights" the community never quite manages to see while assembling outside their suburban homes, however, remain a head scratcher.

Bumperhead is to Hernandez's post-Palomar genre fixations as Richard Linklater's Boyhood is to Sin City: A Dame to Kill For. The bulk of Bumperhead's 120 pages are devoted to Bobby's adolescence and post-high school life following his icy and depressed mother's suicide. Bumperhead arrives amid a half-dozen other 2014 Hernandez projects – is any other artist of his caliber matching either his page counts or range? – with no slowdown in sight. Bumperhead finds Hernandez at his most humane and personal, and, given all the criticism he's taken for his genre work, it's not unlike Quentin Tarantino deciding to make a small, personal film.

If Marble Season is rooted in Hank Ketcham's Dennis the Menace, Bumperhead is once again in Bob Bolling territory, with all requisite blondes and brunettes at hand. A third of the book takes place during Bobby's high-school years. Unlike his friends, Bobby has an easy way with the ladies. "When you can talk to a beautiful woman about stupid shit like UFOs, then you know life is good," he says. Bobby blazes through a series of relationships while staying high and cultivating cultural connoisseurship as a prog- and glitter-rock aficionado who'd rather listen to the Osmond Brothers than the Allman Brothers. "Still listening to your glitter rock, Bobby?" asks a schoolmate. "Still listening to your hippy corpse Grateful Dead music, Duane?" he replies.

The (literal) dark cloud hovering over much of his childhood begins to reappear as high school winds down. One girlfriend has become a born-again Christian, which makes her father cry; one of his childhood tormentors experiences an ego-obliterating acid trip; and Bobby drinks a lot, sometimes with his depressed father, who still doesn't speak English after decades north of the border. Eschewing college for a crappy janitorial job, Bobby bulks up, discovers speed, and has a heart-attack scare. Beto covers a lot of narrative ground, using jump-cuts liberally to get inside a single character's head – as dark as that place is – more than he ever has in the past. Bumperhead is somewhat reminiscent of Julio's Day in its attempt to capture a life's marrow.

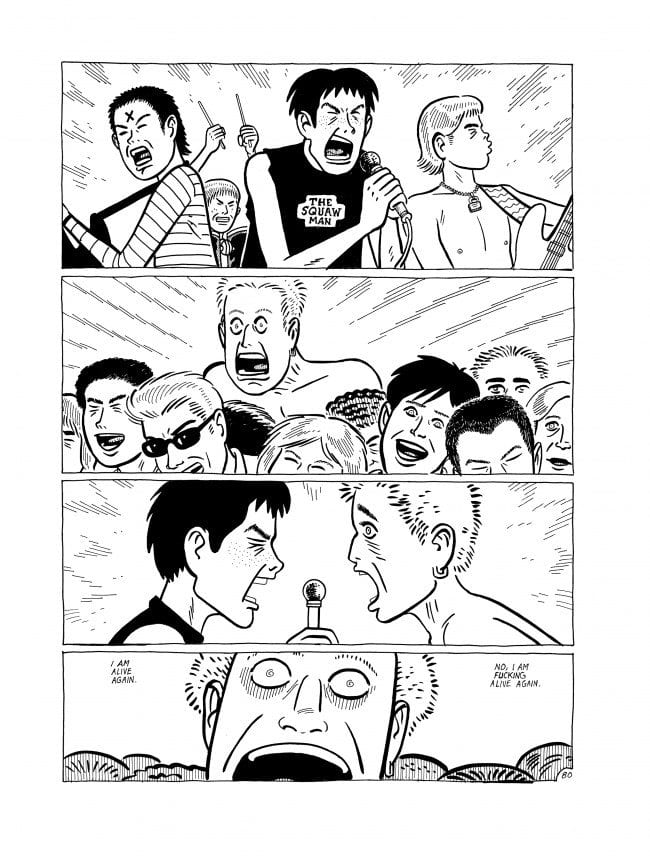

"I am fucking alive again," declares Bobby when he discovers punk rock, whose exhilarating excesses Hernandez captures in a few bracing and exhausting frames.

Even better is an emotionally complex scene in which Bobby take his jazzbo pal Barton to a performance by Los Angeles punk icons X. Hernandez provides Barton with unexpected gravitas, suggesting that the artists sees something in him that Bobby is just too young to grasp.

Even better is an emotionally complex scene in which Bobby take his jazzbo pal Barton to a performance by Los Angeles punk icons X. Hernandez provides Barton with unexpected gravitas, suggesting that the artists sees something in him that Bobby is just too young to grasp.

Bobby is, however, savvy enough to wonder if punk rock is "just an excuse to stay angry all the time." The affirmative answer becomes apparent when he falls in love with Chili, the volatile little sister of the childhood crush who still haunts him. Time, and Chili, march on, however. When Bobby's father returns from Mexico with news about a second family, Bobby checks out from everything, dramatically. There's a sense of a life turned to dust, as Lalo's "iPad" did.

Bumperhead's conclusion is more Six Feet Under than The Sopranos. In the book's final pages, a middle-aged Bobby re-encounters significant figures in his life during a dreamy walk through the woods.

Everyone's the same, only older, and Bobby is little more than a passive listener. That is, until Hernandez's art suddenly blanches out and Bobby confronts his secretive father one last time, satisfaction not guaranteed. Bumperhead's final panel beautifully echoes its first, although Hernandez provides no evidence to bolster Bobby's claim to have lived a "good life." In fact, whether he recognizes it or not, the abyss always gets the last laugh. Perhaps it's not that different from a bullet in the head after all.