From the very first Aleš Kot’s Bloodborne side-story seems hell-bent on convincing fans of the videogame that Kot is of their kind. While more a prequel to than an adaptation of the game’s story, the setting is still the Gothic metropolis of Yharnam on one of the fabled “nights of the hunt” that finds the protagonist and their colleagues in the clandestine order of Hunters taking to the city streets to beat back a rash of plague-infested citizens morphing into nightmarish beasts; while there is exposition enough to allow new readers in, it is clearly made to appeal to those already in the know. Kot is careful to trace a journey not too dissimilar from the one the player might make in a campaign – beating a path from the chapels of Old Yharnam to the Forbidden Woods all the way to the fishing hamlet that closed out the Old Hunters expansion pack – and equally careful to people these locales with a number of unmissable cameos. The first hunter Gehrman, the doctor Iosefka, and retired Djura all play instrumental roles in our protagonist’s quest to save a peculiar, wizened child from the beast hounding him, and are all of them obligated to repeat some of their more memorable lines from the game when they aren’t cribbing their dialogue from item descriptions. Stylistic and aesthetic markers likewise abound to reassure any doubting Thomas that this is Gospel, not some heretical scripture. A brawl at the beginning of the story between a cadre of hunters and horde of beasts functions as much as a showcase of the game’s iconic suite of weapons as it does the narrative and thematic impetus for the nameless hunter’s journey; manifold references are made to the larger lore with everything from explicit intrusions by the Moon Presence to more oblique nods towards entities such as the Orphan of Kos. Even the themes seek to recall the game’s own preoccupation with cycles of violence, parentage, legacy and transcendence by throwing the nameless protagonist into an endless cycle of death and rebirth that threatens to degenerate into eternal, pointless bloodshed...unless they discover the elusive paleblood that promises an escape from it all.

Frankly, it’s an exhausting tack to take: when every reference is so conspicuous, so announced – one panel is nothing but a perfect replication of the game’s infamous game over screen, blood red letters against a black background declaring YOU DIED with taunting superiority – it quickly grows to feel as if this is not so much a story as it is an Easter Egg hunt laid by Kot to distract from the fact that his interest in the game’s world and philosophical preoccupations is passing, if it is anything at all. The result is something deeply uncertain, a book supposedly about the dangers of choosing fear and violence over empathy that is itself so frightened of offending its choosier readers or of facing down the conclusions offered by its inspiration that it opts for a mishmash of styles and ideas add up to nothing but confusion. There are aesthetic clues early on that suggest as much, not least among them Piotr Kowalski’s pencils and Brad Simpson’s colors. Bloodborne’s world is a grim one, yes, and brutal, but it is also grand, cribbing for visual isnpirations as easily from mannerist architecture and Renaissance painting as it does from an H.R. Giger design or Cronenberg movie, something neither Kowalski’s cartoonish sketches nor Simpson’s plain palette do anything to capture. The former has no eye for action. While the hunter talks ceaselessly of how they are ”blood, in movement, dancing with blood,” their fights do not flow as a dance (let alone one manifest in the medium of blood) might. How could they, when half of the time Kowalski relies on a tool as clumsy as speed-lines to portray motion? There is strange, wooden stagedness to the proceedings so pronounced that a decapitated head supposedly flying through the air instead appears to dangle from strings. Perhaps that has to do with the character designs which play at realism but verge on the cartoonish, the eyes of monsters all agoggle as if taken from the sketch pad of a carnival caricaturist, the forms of the humans rigid and unbending as if they only existed in two dimensions. Nothing here is as strange or wild or bizarre as it needs to be.

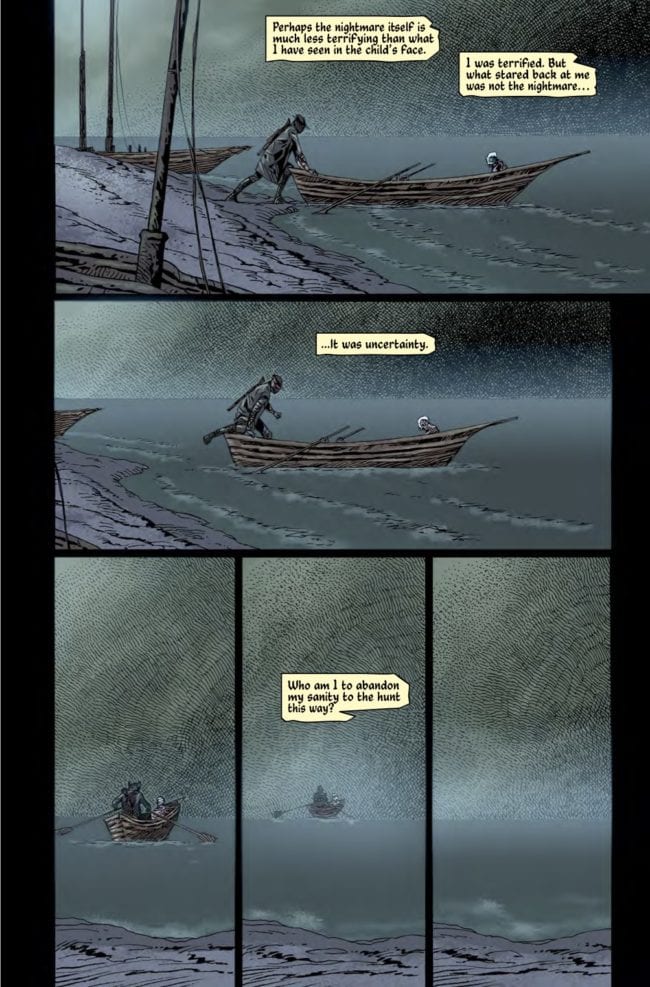

Frankly, it’s an exhausting tack to take: when every reference is so conspicuous, so announced – one panel is nothing but a perfect replication of the game’s infamous game over screen, blood red letters against a black background declaring YOU DIED with taunting superiority – it quickly grows to feel as if this is not so much a story as it is an Easter Egg hunt laid by Kot to distract from the fact that his interest in the game’s world and philosophical preoccupations is passing, if it is anything at all. The result is something deeply uncertain, a book supposedly about the dangers of choosing fear and violence over empathy that is itself so frightened of offending its choosier readers or of facing down the conclusions offered by its inspiration that it opts for a mishmash of styles and ideas add up to nothing but confusion. There are aesthetic clues early on that suggest as much, not least among them Piotr Kowalski’s pencils and Brad Simpson’s colors. Bloodborne’s world is a grim one, yes, and brutal, but it is also grand, cribbing for visual isnpirations as easily from mannerist architecture and Renaissance painting as it does from an H.R. Giger design or Cronenberg movie, something neither Kowalski’s cartoonish sketches nor Simpson’s plain palette do anything to capture. The former has no eye for action. While the hunter talks ceaselessly of how they are ”blood, in movement, dancing with blood,” their fights do not flow as a dance (let alone one manifest in the medium of blood) might. How could they, when half of the time Kowalski relies on a tool as clumsy as speed-lines to portray motion? There is strange, wooden stagedness to the proceedings so pronounced that a decapitated head supposedly flying through the air instead appears to dangle from strings. Perhaps that has to do with the character designs which play at realism but verge on the cartoonish, the eyes of monsters all agoggle as if taken from the sketch pad of a carnival caricaturist, the forms of the humans rigid and unbending as if they only existed in two dimensions. Nothing here is as strange or wild or bizarre as it needs to be.

Simpson, meanwhile, has no eye for light or detail. There is little sense of dimension in these environments owing to the lurid color scheme that relies almost exclusively on a limited palette of fiery reds, royal rich blues and drab browns to fulfill every possible role.

Other elements of style attempt to rein in these more lurid elements, but to no avail. Characters speak with an elevated diction designed to lend every utterance a significance and portentousness that suggests these characters live perpetually on the edge of some grand metaphysical revelation that will send them over the brink. “I am not one to assign certainty to patterns which escape the wholeness of perception,” the nameless hunter at the story’s center mutters when asked a question they cannot – or do not dare – answer, while Gehrman punctuates a letter with the Socratic-derived maxim that “I only remember I truly do not know anything at all.” Over-wrought boxes of narration riddle what feels like every panel with glimpses into the mind of a protagonist given endlessly to musing in tortured prose about the futility of “the Hunt” (here a metaphor for violent conflict). It’s not unfitting given the language used in the game, or that both game and comic draw liberally from the style of classic cosmic horror authors like Lovecraft who favored exactly such an antiquated writing style, but the conceit is at odds with the narrative here presented. But at least in the game there might be hours between lines of dialogue; the remainder of the time left alone in the world and so perfect prey for feelings of paranoia, atomization. At least in pure prose the narrator’s voice trapped you in their anguished perspective, isolating you from the rest of the world the better to frighten you with the sense that perhaps they were right to live in such fear. Here, though, in this fast-paced action story, there is no time for silence or meditative lingering on the literal and spiritual emptiness of these environs. Not when the protagonist cannot stop rambling about “Dying and returning, forever a circle, an inescapable, bleeding hollow in the side of the world.” And so there is little chance for the horrors to come creeping in. It’s too noisy for doubts that there’s something very, very wrong with this world to be heard; in what silence could subtle insinuations make themselves known? It’s too bright, too lively for the monsters to make their home; out of what unlit corner might they come crawling? And what threat worse than dismemberment could they offer?

Other elements of style attempt to rein in these more lurid elements, but to no avail. Characters speak with an elevated diction designed to lend every utterance a significance and portentousness that suggests these characters live perpetually on the edge of some grand metaphysical revelation that will send them over the brink. “I am not one to assign certainty to patterns which escape the wholeness of perception,” the nameless hunter at the story’s center mutters when asked a question they cannot – or do not dare – answer, while Gehrman punctuates a letter with the Socratic-derived maxim that “I only remember I truly do not know anything at all.” Over-wrought boxes of narration riddle what feels like every panel with glimpses into the mind of a protagonist given endlessly to musing in tortured prose about the futility of “the Hunt” (here a metaphor for violent conflict). It’s not unfitting given the language used in the game, or that both game and comic draw liberally from the style of classic cosmic horror authors like Lovecraft who favored exactly such an antiquated writing style, but the conceit is at odds with the narrative here presented. But at least in the game there might be hours between lines of dialogue; the remainder of the time left alone in the world and so perfect prey for feelings of paranoia, atomization. At least in pure prose the narrator’s voice trapped you in their anguished perspective, isolating you from the rest of the world the better to frighten you with the sense that perhaps they were right to live in such fear. Here, though, in this fast-paced action story, there is no time for silence or meditative lingering on the literal and spiritual emptiness of these environs. Not when the protagonist cannot stop rambling about “Dying and returning, forever a circle, an inescapable, bleeding hollow in the side of the world.” And so there is little chance for the horrors to come creeping in. It’s too noisy for doubts that there’s something very, very wrong with this world to be heard; in what silence could subtle insinuations make themselves known? It’s too bright, too lively for the monsters to make their home; out of what unlit corner might they come crawling? And what threat worse than dismemberment could they offer?

All this assumes Kot was ever interested in telling a horror story at all, though. For all the endless reliance on the iconography and imagery of Bloodborne – a cosmic horror story as accomplished as any example of the genre – The Death of Sleep is less concerned with exposing characters to their insignificance and the pettiness of their every attempt at constructing meaning or control in an indifferent universe than it is in offering a reassuring fable that human morality and effort are inherently valuable. The nameless hunter’s quest to protect their young charge from their own doppleganger functions as a bald metaphor for their quest to shepherd their remaining scraps of humanity towards some kind of enlightenment lest they succumb to their animal instinct for violence, while their final decision to spare the grotesquely transformed child they’ve invested so much in proves that they have learned it is not bloodshed but empathy that will free them from their own existence as a kind of Asura locked in a hell of perpetual battle. It’s a reassuring tale built to offer warmhearted assurance of escape couched in the most superficial of Bloodborne’s trappings, wherein the “pale blood” so often mentioned in game as a medium for transcendence ends up here allowing for a very literal and pat moral salvation.

But to think that all these simple signifiers added up to the whole of Bloodborne and of director Hidetaka Miyazaki’s preoccupations is to misinterpret them entirely. There was as much talk in the game as here of cycles, of spirals, of eternally recurrence and the desperate attempt of all stripes of characters to transcend the same, but it was always telling that of the game’s three endings only one offered an escape from the patterns that defined the world, and then only through transcendence into a form alien and incomprehensible. Rising above the hell of this world was achieved not through embracing one’s better angels, no; no matter how many NPCs you spared or quest lines you resolved with mercy, your final choices remained the same. And if the Old Hunters expansion packed allowed players a chance to discover the root cause of these patterns – to address the original sin that tainted this universe to begin with– it ultimately allowed them only an act of brutal mercy that granted Gehrman no absolution greater than one peaceful night of symbolically meaningful slumber.

But to think that all these simple signifiers added up to the whole of Bloodborne and of director Hidetaka Miyazaki’s preoccupations is to misinterpret them entirely. There was as much talk in the game as here of cycles, of spirals, of eternally recurrence and the desperate attempt of all stripes of characters to transcend the same, but it was always telling that of the game’s three endings only one offered an escape from the patterns that defined the world, and then only through transcendence into a form alien and incomprehensible. Rising above the hell of this world was achieved not through embracing one’s better angels, no; no matter how many NPCs you spared or quest lines you resolved with mercy, your final choices remained the same. And if the Old Hunters expansion packed allowed players a chance to discover the root cause of these patterns – to address the original sin that tainted this universe to begin with– it ultimately allowed them only an act of brutal mercy that granted Gehrman no absolution greater than one peaceful night of symbolically meaningful slumber.

It was no wonder that things should end this way: the world of Bloodborne is a fallen one that contrasts the iconography and ritual of Catholicism against the nihilistic imagery and philosophies of cosmic horror to expose the lie of escape in a material universe. One can seek spiritual ascension and healing through a church that offers holy communion literally derived from the flesh of higher existences, but no matter how strange it is the flesh is still simply flesh, the salvation it offers nothing but a temporary cure for your fallen condition. Blinding oneself to this horrific knowledge is no escape; it’s no coincidence that to a one the blindfolded characters encountered throughout the game eventually transform into the vilest of beasts. Yet neither was trying to adjust as a human to this horrible truth any more fruitful; more often than not those who pursued the route of enlightenment through knowledge were left as gibbering and broken as the protagonist of any classic cosmic horror story. Only by moving into spaces both biologically and morally and philosophically alien could one escape the reality that kindness, nobility, and all mortal striving offer no escape from the inevitable in a universe inherently antagonistic to all fleshly life. To offer a simplistic parable that suggests our best nature will eventually help us overcome our worst (and literal) demons is a mission entirely at odds with Bloodborne’s most prominent themes.

It’s almost too telling that Kot chose to set the conclusion of his story in the same fishing hamlet that wraps the original game’s expansion pack. In lore it’s a location that has been lost to time, a piece of the hunter’s collective history now hidden in dreams because it reveals the unholy nature of their origins and the moral bankruptcy of their actions. In a world where secret knowledge is guarded jealously it is the greatest of secrets and so most jealousy guarded. In Kot’s vision it is a location in the physical world well known enough that the protagonist mentions it off-hand and the doctor Iosefka hands out maps that lead directly to it. It not only makes no sense that knowledge of the hamlet’s location and history would be well known; it actively undermines its purpose. Harping on such a discrepancy must sound like the pedantic whining of a jilted super fan (Musn’t there be an actual fishing village the one in dreams is based on? Why not end the story there for a clever bit of echoing?) but Kot’s decision to finish his story with a misused reference to the game betrays not a lack of reverence for the source material so much as a lack of interest in its structure and themes.

So then The Death of Sleep does not fail because it does not stoop to simply retelling the narrative of Bloodborne itself. No. It does not fail because it tries to do something brave and new with a beloved property at the risk of upsetting its fans. It fails because it does nothing to convincingly build off of its supposed inspiration. It fails because it seems to care so little for anything but the most superficial elements of its inspiration that at times it appears actively frightened of its conclusions and swerves away in fear of becoming the same. If its tale had been one of a minor but cutting humanity meant to skewer the moral shallowness of cosmic horror’s central nihilism, if it had demonstrated that such a philosophy’s power is limited in contrast to a deeply moving story about individuals coming to find purpose and companionship even in the face of such horrors, if it had simply bothered to argue how Miyazaki’s visions of a fallen material condition are themselves rooted in a warped kind of Cartesianism that creates rather than reveals the horror of our experience, even that would have been worthy. No, Bloodborne: The Death of Sleep does not fail because it deviates too far from the source material or because it will not dare deviate. It fails because it does not uphold the same standard of unflinching honesty that its inspiration did. It fails because it is a horror story afraid of nothing so much as itself.