They have brushes for the buffalo and shears for the goat. They won’t trim a Mahar’s [untouchable’s] hair—they’d rather cut his throat.

Early in Bhimayana, a boy named Bhim experiences the world through violence. Bhim is a Mahar, an untouchable. He knows it’s no fun being one. His gentle face and Bambi eyes in the comic’s version are nobody’s idea of a kickass superhero, but when he grows up Bhim will become exactly that.

Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar (1891-1956) was a leading champion of affirmative action, his labours anchored to the colossus of caste, though often he is only blandly credited with designing India’s constitution. Beginning in the 1920s, he became the country’s most vociferous conscience, criticising Hindu society’s oppression of women and dalits (formerly untouchables) as being inherently anti-democratic. Armed with the liberal crux of reformers such as J.S. Mill, John Dewey, and Booker T. Washington, Ambedkar developed a model of social justice that was widely vilified by nationalists and even by Gandhi, whose own esteemed mandate of freedom comes away looking like the political charter of a posh boy fraternity. Bhimayana (2011) is a graphic account of Ambedkar’s crusade to eradicate untouchability.

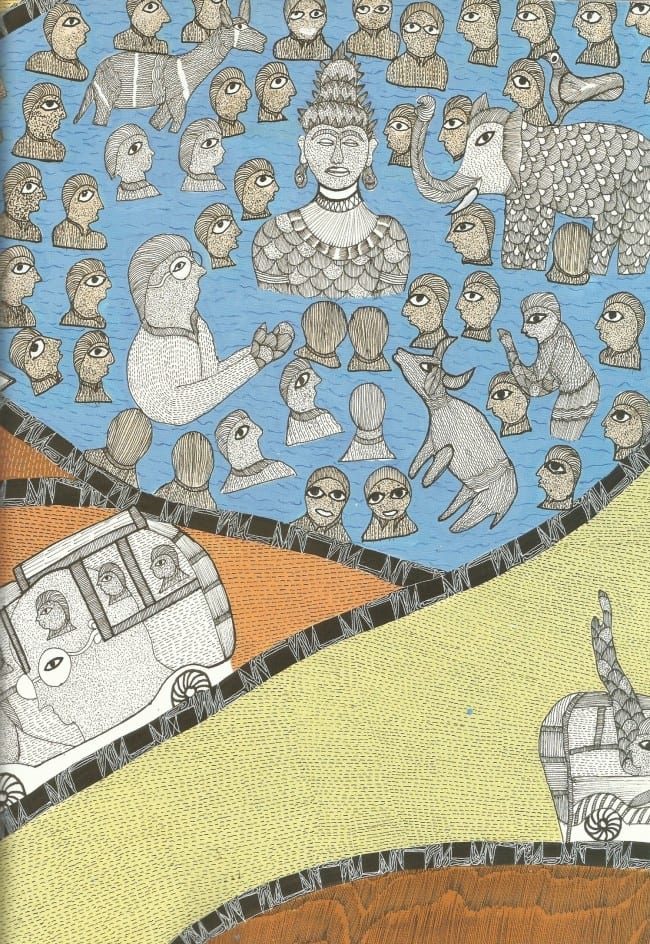

Frankly written and drawn in the mnemonic idiom of modern Gond art (as practiced by the central Indian tribal politic called Gond), the book ends up beautiful, punchy, and always readable. Bhimayana brings together writers Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand and Pardhan Gond artists Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam. Along with dalits, the Gond and other tribal civics are India’s protected peoples called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SC/STs). Bhimayana was published by Navayana Publishing, a niche press founded in 2006 that focuses on the history and politics of caste in India. S. Anand, one of the book’s writers, is Navayana’s founder-editor.

Mainly two-dimensional and rich in natural motif, Gond drawing tells stories through visual aide-mémoires that artists once applied exclusively to domestic architecture. It’s vibrant in imagery but only tentatively narrative. Yet, recent exponents, like Bhimayana’s artists, owe their ken to artist Jangarh Singh Shyam (represented on the dedication page), who in the 1990s, urged to go professional, substituted multi-coloured clays with paints and ink used on canvas and single-sheet paper.

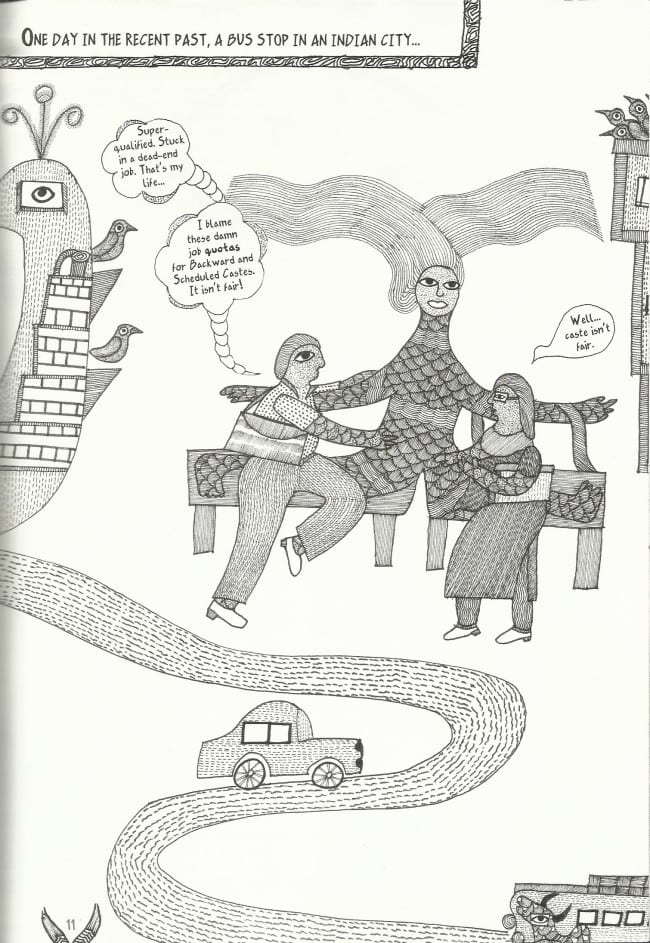

Beyond this graphic pedigree, the book is also unusually germane for being grounded in present-day journalism. Its two interlocking strands join Ambedkar’s biography with a string of thumbnails about present day caste prejudice, violently pervasive in villages, though all but invisible to most urban Indians. The barbed but seductive quality of this double narrative, the fact that yuppie ignorance is sometimes too easily mocked, makes it that much more impossible to resist second and third readings. This robust exposé about caste is not afraid to tell it like it is—that if you think caste is dead, think again.

§

Former untouchables were outcasts flushed outside the four-level Hindu caste structure topped by brahmins (priests) that was codified about 1500 years ago. They were described as impure and relegated to the rank of those who should not be touched. In reaction, Jotirao Phule, a 19th century anti-caste theorist and reformer, was first to refer to untouchables as ‘dalit,’ which means ‘broken people.’ Ambedkar typically used ‘Depressed Classes’. Meanwhile, Gandhi popularised ‘harijan’ or ‘children of Hari,’ Hari being is the name of a central Hindu god.

But after 1974, when a militant anti-caste movement led by the Dalit Panthers (inspired by the Black Panthers) was crushed by right-wing Hindu political parties working for the state, dalits ditched Gandhi’s benevolent jargon. For being linked to a Hindu god meant only more Hindu bondage. They went with ‘dalit’ to oppositely assert reconstitution and, presumably, also give the finger to its real meaning.

Historically, dalits were reduced to performing jobs caste Hindus found polluting. They handled dead people and animals, soil, and waste respectively as cremators, cobblers, potters, gardeners, sweepers, and scavengers. Those who farmed were landless and indentured.

Penury was common, though Ambedkar’s family, like some others from western India drafted into the British army, managed to feint utter poverty. Yet, all untouchables were denied basic civic necessities. Grocery shops were open to limited access. Primary schooling became available only because of British law. Using wells and temples and building imperishable houses was entirely off-limits. Verbal humiliations, thrashings, and fatal threats were givens.

In seeking to reclaim what he called “human personality,” Ambedkar’s call to “educate, organize, and agitate” became a rallying point in his movement for social justice. The first big push came after 1924, when the Bombay Legislative Council’s decree requiring untouchables to be granted access to all public utilities was universally disobeyed.

Collaborating with various progressives, Ambedkar became a leading voice in slowly organising dalits until finally, in 1927, a protest march of 3000 walked peacefully to a town called Mahad where they drank from a tank so far reserved for caste Hindus. This event is known as the First Mahad Satyagraha of 1927. Symbolic but momentous, Ambedkar compared its potential to that of 1789 French National Assembly that abolished aristocracy and liberated the poor. Later that year, he led 10,000 dalits in the Second Mahad Satyagraha. There he burned a copy of the Manusmriti (Laws of Manu), a Hindu text that apparently records the words of the universe’s founder Manu who advises torturing untouchables, forcing them into poverty, and subjugating women.

Almost instantaneously, Ambedkar’s decisive segue to dalit political representation put him out of favor with the nationalist elite who called his demands for equality divisive and thus detrimental to India’s struggle for self-rule. In 1932, Gandhi, the holy cow of the Indian freedom movement, went on an indefinite hunger strike, forcing the British to reconsider granting untouchables separate electorates. For Ambedkar, the schism exposed the nationalist Congress party’s doublespeak on caste. Gandhi, who was the Congress’s spokesperson, sought Indian freedom at the cost of silencing minorities; Ambedkar envisioned India first freed from itself, or from Brahminism, which he classed with “the negation of liberty, equality, and fraternity,” a doctrine that became a crucial punching bag in his best-selling Annihilation of Caste (1936).

Over the next fifteen years, Ambedkar spoke and published widely on various issues impacting dalits, such as water policy, agriculture, military reform, labour rights, and Buddhism. Meanwhile, his unabated resistance to the skewed politics of the freedom movement ended in a book released on the eve of India’s independence. His damning critique in What Gandhi and the Congress have done to the Untouchables (1946) leaps off the title page with a quote by Thucydides: “It may be in your interest to be our master, but how can it be ours to be your slaves?”

Despite this, Ambedkar’s polymathic abilities were sought after for the highest privilege. In 1947, the Congress party heading the new government invited him to serve as independent India’s first Law Minister. He became Chairman of the Drafting Committee of India’s constitution and later drafted the Hindu Code Bill, which sought to confer property and divorce rights on women, legalise monogamy, and introduce gender equity. For Ambedkar, it was the country’s most crucial reform, but after a long wait, the Constituent Assembly rejected the bill in a majority vote.

Ambedkar snapped. In 1951, he resigned from the Cabinet with strong words for Jawaharlal Nehru, the Prime Minister, and his peers’ perceived betrayal of comprehensive democracy. His parting speech called inequality the very soul of Hindu society that if left untouched was “to make a farce of the Constitution and to build a palace on a dung heap.”

Within five years, Ambedkar lived up to his old promise to reject Hinduism for an ethically sound religion. In October 1956, about six weeks before he died, he converted to Buddhism along with an approximate 500,000 followers. Considered to be the largest single conversion in human history, it inspired many dalits to voluntarily seek monotheistic faiths. They became Christians, Muslims, and Sikhs, though conversion did little to dissolve the stigma of untouchability.

§

Aptly, Bhimayana’s central character is not Ambedkar alone but also the degrading grind of dalit life among the 60 million in Ambedkar’s time. Both are selectively based on his speeches and the little-known Waiting for a Visa (c.1935-36), a brief autobiographical text in which Ambedkar charts his political education through a litany of life-altering episodes. Hence, the title Bhimayana, which could be a cheeky send-up on the Ramayana, a pivotal Hindu text that recounts the high-caste mythical god prince Ram’s exile from everyday royal luxuries. Bhimayana’s account of everyday expulsions from ordinary civic dignities — water, shelter, and travel — presents an alternative epic of heroism.

The narrative begins with a socially-literate woman and a blinkered man discussing affirmative action in education and jobs, the most common peeve against dalits. The man finds setting quotas aside for dalits unfair. “Oh yeah?” says the woman, and instead refers him to the September 29, 2006 massacre of dalits in Khairlanji, a small village in Ambedkar’s native state of Maharashtra, an alleged bastion of contemporary dalit activism.

For two hours before being dumped into a canal, four members of a dalit family called Bhotmange were variously mutilated, raped, and bludgeoned to an audience of forty village residents. The events were suppressed for over a month. Dalits, mainly lead by women, did not break out into mass protests until a month after the event when a popular blog described the event, suggested state complicity in a cover-up, and encouraged agitation. Predictably, the government suppressed the protests under the charge of waging war against the Indian state.

In using the word Brahminism for such vicious conventions during his time Ambedkar was of course defining more than Brahmins discriminating against untouchables. For him, Brahminism was the very pathology of Indian bigotry ingrained even in non-Hindus, including Muslims, Christians, and Parsis that he foresaw migrating poisonously in low-caste Hindus who history allowing would assume the role of Brahmins. He was right. At Khairlanji, it was low-caste Hindus, not Brahmins, who lynched the dalit Bhotmanges. Note especially why the Bhotmanges were lynched: They were being punished for educating their only daughter, protecting their land from encroachers, and living with the maximum poise their finances would allow, basically exactly what Manu forbids untouchables to covet in the Manusmriti (Laws of Manu).

Bhimayana uses Khairlanji (not exceptional, but emblematic of caste in India) to set off a domino-like chain of news items about dalit lynchings that thematically intercut the three main events of the Ambedkar story and his various political feats, including the Mahad Satyagraha, Ambedkar’s differences with Gandhi, the Constitution, and the Hindu Code Bill.

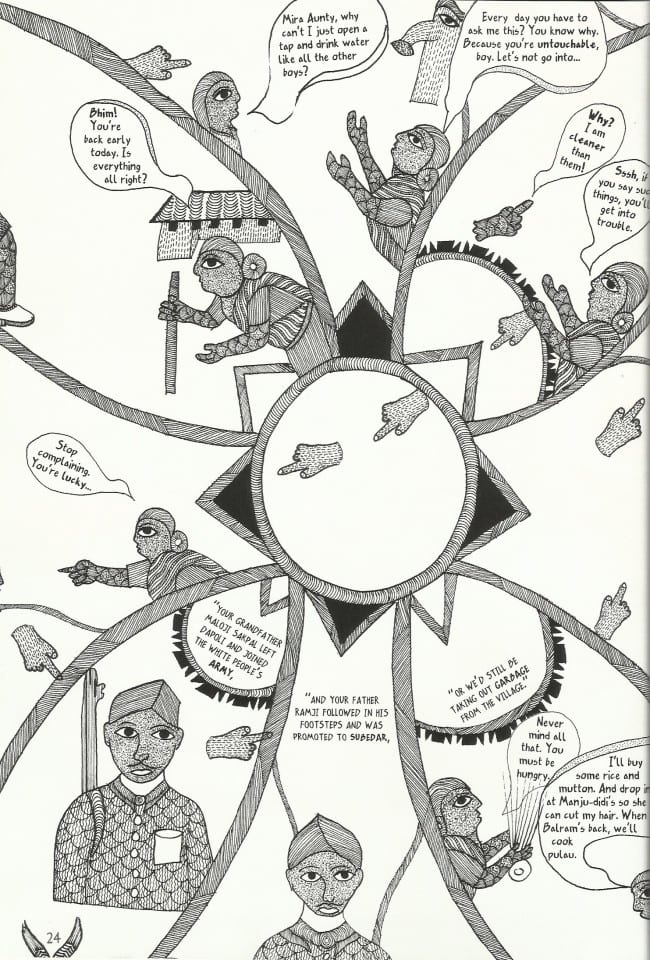

Book 1: Water is set in 1901, a landmark year in Indian education as Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, is initiating educational reforms to help Indian students find better jobs. This is fantastic news for the rich, who can afford higher education.

But back in Satara, Bhim is set apart at play and in the classroom. He’s also having a tough time just getting a glass of water. From the school water pump to the village trough, untouchables are denied access at every turn. At one point, a teacher farcically blames Bhim’s thirst on his long hair. The child himself would love a trim, but from whom exactly? Barbers won’t touch untouchables. Through such gentle ironies Bhim’s confusion at caste inequality expresses the wrench in simply being dalit: “Animals enjoy more freedom”.

Book 2: Shelter jumps to Ambedkar’s thwarted efforts to put a roof over his head. It’s 1918. He is en route to work for the Maharaja of Baroda who had sponsored his education at Columbia University, New York. In Baroda, unable to lodge at a Hindu hotel (because he might be found out and killed), Ambedkar suffers a dungeon-like room at a Parsi inn, though even this ends in threats to his life. For almost a fortnight he is compelled to hide in public spaces after work. Broken and disillusioned, Ambedkar quits his job and returns to Bombay.

Book 3: Travel is set in 1934. Ambedkar is 43 and a recognized dalit leader with various agitations behind him. Now he is on bus tour with a contingent of political workers. Initially thrilling, the journey ends disastrously when the bullock cart transporting him to his destination in the dalit village meets with a serious accident. The man driving the cart is an unskilled man because no regular driver would risk being polluted by the untouchable Ambedkar.

Continued