Quiet desperation is, by definition, not always easy to detect, but at this point, it’s been pretty well documented—in and out of comics. Into this tradition of desperation art comes Beverly, the debut collection of cartoonist Nick Drnaso. The book presents a series of vignettes about a frustrated, fatigued Middle America. Its stories are economical, painful, and—for better or for worse—familiar.

Drnaso begins Beverly with “The Grassy Knoll”, a concise, spare bit piece of cartooning about Sal, a roadside cleanup worker who alienates everyone around him, told from the perspective of a young colleague who can’t get away from the guy fast enough. Later stories include “The Lil’ King”, which sees a family vacation derailed by a moment of confused teenage sexuality, “Pudding”, in which estranged childhood friends fail to reconnect at a party, and others. Each entry contains a number of perversely effective formal choices.

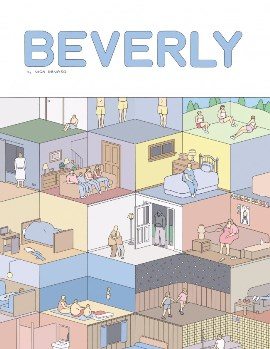

Drnaso works in something akin to the ligne claire style, never opting to vary the width of his thin, tidy linework, yet his pages don’t pursue the dynamism of clear-line masters like Hergé or Joost Swarte. Even moments that could be depicted as fluid sequences typically appear as montages instead, with minute shifts in location or perspective between panels. The decision does as much as any plot beat to convey Drnaso’s vision of a lethargic Midwest. We’re not in Europe anymore.

Beverly features a pastel palette, but in wide-enough swaths and with enough muted beiges, browns, and creams to preclude a sense of lightness. Even when Drnaso shifts from a twelve- to a sixteen-panel grid, or from sixteen panels to twenty-four, a reader finds not the expected uptick in pacing but a subsumption of the grid to the book’s foot-dragging gait. Every element works together in the kind of theoretically straightforward arrangement that only the best cartoonists actually pull off.

Beverly features a pastel palette, but in wide-enough swaths and with enough muted beiges, browns, and creams to preclude a sense of lightness. Even when Drnaso shifts from a twelve- to a sixteen-panel grid, or from sixteen panels to twenty-four, a reader finds not the expected uptick in pacing but a subsumption of the grid to the book’s foot-dragging gait. Every element works together in the kind of theoretically straightforward arrangement that only the best cartoonists actually pull off.

And Drnaso’s elders have noticed. A cover blurb from Chris Ware reads: “A debut book by a young writer-artist who has not only absorbed but also advanced beyond the comics which have preceded him. Beverly is the finest and most electrically complex graphic novel I’ve read in years.” This is an effusive endorsement from one of the greatest cartooning talents living or dead, and damning in its own way. What book could live up to those words, from that artist?

At minimum, Beverly is a work that many of Chris Ware’s readers will warm to, in part because it shares the cool temperament of Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan and Rusty Brown stories. And although Beverly doesn’t have the symphonic qualities of those works or the sheer technical virtuosity, that’s not really the point. If Ware weaves a tapestry of despair for his readers, Drnaso has opted to smother them with a gloom pillow. It’s a valid, effective approach, though it leaves Beverly open to similar critiques. Douglas Wolk’s knock on Ware—“an emotional range of one note”—has become less apt as Ware has expanded that range in Building Stories and other recent projects, but it comes to mind while reading Beverly, and Drnaso has fewer formal diversions to offer.

The tonal monotony of Beverly is also, of course, a kind of tonal coherence, the kind many of Drnaso’s peers are still reaching for. If it’s a problem, it’s a good problem to have. The book is consistent and uncompromising, the product of obvious control. But it nonetheless brings to mind the words of another of Drnaso’s predecessors: “Is that all there is?”

The tonal monotony of Beverly is also, of course, a kind of tonal coherence, the kind many of Drnaso’s peers are still reaching for. If it’s a problem, it’s a good problem to have. The book is consistent and uncompromising, the product of obvious control. But it nonetheless brings to mind the words of another of Drnaso’s predecessors: “Is that all there is?”

Another way of putting it: Beverly is so accomplished in its execution—the how—that it invites larger questions about the why. As quaint as it sounds, what does art like this do for a reader? It certainly doesn't expose Middle America as a land of diminished hopes and isolated people—Americans are comfortable enough with this concept that an absurd crypto-fascist can run for office while selling them “Make America Great Again” baseball caps. The fatigue of Beverly is mainstream, the desperation louder than ever, even if Nick Drnaso’s politics are presumably miles away from those of Donald Trump. So what truths in Drnaso’s comics might elude readers without the benefit of his work?

Art for art’s sake is one thing. Beauty is an end in itself. Yet the various aesthetic effects in Beverly work—in no small way—in service of the narrative content, and in service of a specific understanding of contemporary American life. Drnaso’s exploring not merely the comics form but also a time and a place. And his comics stop short of articulating a critique of this time and place that reads as wholly new or unavailable elsewhere. That, of course, is a shortcoming only by the largest-possible measuring stick. As a debut, Beverly is rare in its assurance and precision, a feat of obvious commitment and craft. Like any window, the book has its limitations, but the view is chilling nonetheless.