“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina’s epigrammatic first line might have been written about Alison Bechdel’s first book, Fun Home, which nimbly portrays her family’s daily negotiations with her angry, closeted father alongside a retelling of her coming out as a lesbian. Tolstoy’s focus on family as the seat of profound individual conflict immediately preceded Freud’s positing of the family as the nexus of experience and development. The latter’s theories make brief, unnamed appearances throughout the book. So do a number of works of literature: if not Tolstoy, then Fitzgerald, Colette, Proust, and Shakespeare. This is, in fact, one of Bechdel’s most appealing qualities as a nonfiction writer: she wends her way through personal experiences using literature as a guide, enacting close readings of both and illuminating knotty relationships in the process. (In this regard, her writing strongly reminds me of Elif Batuman’s essays in The Possessed.) Her narrative—both stylistically and literally, as comics—becomes, as she says in Fun Home, a “novel fusion of word and deed.”

But if Fun Home is a riveting Tolstoyan family tale—sophisticated and nuanced in its depictions and movement—then Bechdel’s new book, Are You My Mother?, is decidedly Freudian in its language and methods: keenly analytic, explanatory, and often clinical. In short, it’s little fun to read. There is none of the poetry one finds in really good writing, none of the storytelling magic that is everywhere in Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun Home.

In a recent interview, Bechdel thumbnails the difference between her two memoirs. Donald Winnicott, the nineteenth-century object-relations-theory pioneer who dominates Mother, wrote, Bechdel notes, "that the mother must be dismantled whereas the father can be murdered. And I feel like somehow I murdered my dad, and that was really a walk in the park. That was so much easier than dismantling my mother.” The distinct method of approaching each parent is evident in the structures of the two books. Fun Home comprises a straightforward narrative that leads, by way of a discernible timeline, to a resolution with her father; Are You My Mother? is a jumble of parts that aren’t always arranged in a way that makes visible the whole body of the story.

Where Bechdel sought in Fun Home an understanding with her deceased father, in Mother she seeks to do the same with her mother. Even the best mother-daughter relationships are fraught, and theirs is far from easy. There is more for Bechdel to wrestle with here, too, because her mother is still alive: there is no neat time period, as there is with Fun Home, and the lives and problems on the page extend beyond the book’s temporal borders. Mother’s complexity stems in part from the peculiar displacement of maternal affection and solicitude that gives the book its searching title. It revisits some of the childhood scenes from Fun Home, spinning out the details of then-minor moments into occasions of consequence, and Bechdel again employs literature in her quest—excellent readings of Adrienne Rich and Virginia Woolf, in particular—but therapy and psychoanalysis, namely, Winnicott's writings, govern the book’s themes and structure.

Memoirs, even if they’re meant to describe the life of a person other than the author, are necessarily in part about the author—the story is, after all, from his or her perspective. Though Fun Home thoroughly traces her father’s life and works to show his interior life, the must haves and probablys Bechdel uses in imagining things he might have said or done make her the subject as much as her father; it is every bit about endeavoring to know a man she felt she may not have fully known. Mother, however, reveals little about its ostensible subject. There are too few details about her relations with her mother—we revisit some of the same events, each time with a new set of tools (courtesy Winnicott) with which to dissect the moment, to peer deeper into its inner workings, its dark corners. The results are sometimes fascinating—such as the multiple viewings of the same play at different points in the timeline—but it’s unfair to the potential richness of the narrative (and to the relationship) to make a handful of scenes stand in for five decades of mothering and daughtering.

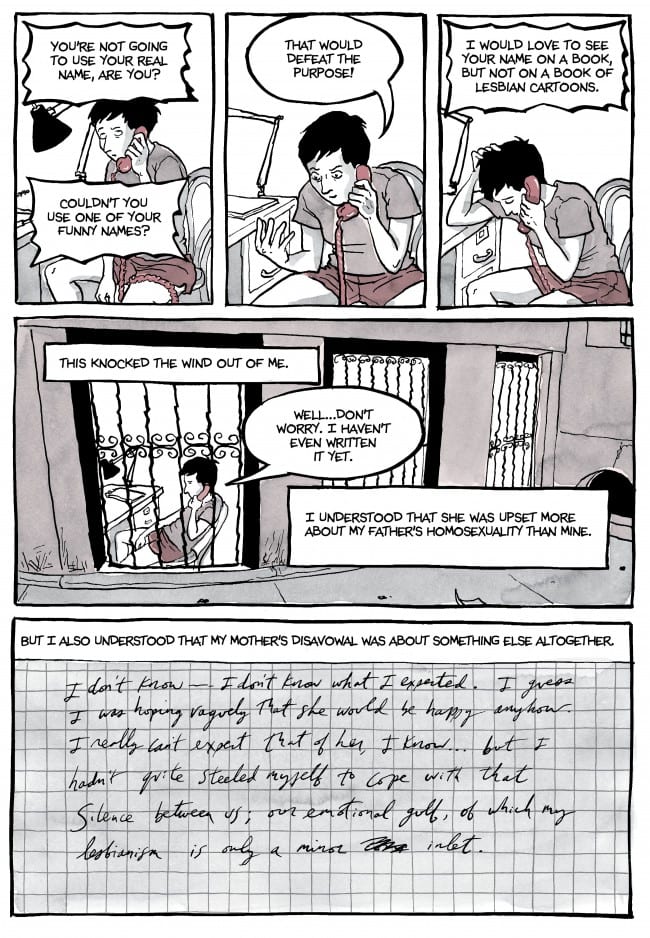

Even the matter of the book’s subject is up for debate. It is presented as a memoir of her relationship with her mother—a parallel to Fun Home—but midway through, Bechdel describes the book as being about her mother and Winnicott. And, indeed, so prominent is Winnicott in the narrative that Bechdel seems more fascinated by the way in which his theories dovetail with and spell out the details of her maternal quandary than she is in fleshing out her emotional life or her mother’s. Where in Fun Home she wound her story round and into her father’s, here she weaves it into Winnicott’s, and this framework, relying heavily on quotations from Winnicott’s writing and on analytic lingo, is inorganic. Likewise, her images are less about conveying action and furthering the narrative than illustrating the slow progress of her self-analysis. There seem to be many, many pages of Bechdel in therapy, on the phone with her mother, and in conversation, as well as any number of panels containing transcribed texts. Nearly every panel contains a caption; too few use dialogue.

In broaching the subject of Winnicott to her mother, Bechdel inserts him—his theories and experiences—into their relationship. The psychoanalysis serves as a thick layer between Bechdel and her mother, and that distance makes it oddly impersonal. Nothing is quite what it seems. “Instead of playing a character, I’m playing myself,” Bechdel writes; and elsewhere: “I employ these allusions to James and Fitzgerald not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms.” Wary of taking a trip with her mother to the theater, the adult Bechdel notes, “I suppose it only makes sense that I feel closest to my mother with not just a play between us, but a play about acting. A self-reflexive mis-en-abîme.” Like the relationship itself, the telling of it is predicated on proxies—psychology, Winnicott, literature, acting (Bechdel draws from photographs of herself that she snaps with a camera timer, occasionally miming the emotions she needs to capture). What’s lost in this series of proxies is, as Bechdel says of the translation of Proust’s title A les Recherches du Temps Perdu, is the “complexity of loss itself”—in this case, not only what is lost but also the complexity of what she has gained by book’s end.

Of the diary of one of his patients, Winnicott observes, “The meaning of the diary now became clear—it was a projection of her mental apparatus, and not a picture of her true self.” Bechdel’s book is based heavily on her diaries, as she shows throughout Mother. She also internalized Winnicott’s writing, recording significant passages in the book itself, as though it—the memoir—has become a new diary. We don’t frequently enough see her working through her problems, but are told often by way of these and other quotations from outside sources how the solutions came about. As such, there is little for the reader to do, other than follow the progress of her therapy.

Still, unlike so many memoirs, Bechdel is never clever for cleverness’s sake. Ideas and emotions are her primary material, and she works with them far more honestly than the majority of memoirists publishing today. She seeks to explore personal emotion in an unabashedly intellectual way, and reading—and thinking about—her efforts is consistently rewarding.