Despite the terrific influence Japanese comics have had on small-press and online-focused cartoonists here in the English-speaking west, it's still pretty rare to encounter the Japanese equivalents of those none-too-mainstream artists in translation. Much of what is presented as 'manga' to overseas readers is very much commercial entertainment - because Japan's industry of comics is comparatively very healthy, there are many more professional working cartoonists, and a wider net can thus be cast into the stream of popular genres and topics; it's more akin to cable television than anything familiar to English-language comics. As a result, even if you stick to the biggest publishers and the more formulaic titles, 'manga' will appear to be more diverse. But smaller manga do sometimes get through. Just last month, the Tokyo bookstore and art gallery Popotame put out an English-translated selection of comics titled Popocomi, for release at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. This follows a 2016 English edition of the Japanese indie manga anthology USCA from Diorama Books, and 2018's š! #32, a Latvian-assembled showcase for Japanese artists. Among larger publishers, we must not forget that Kabi Nagata's hugely-acclaimed memoir My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness (published in English by Seven Seas) began its life as a personal webcomic, or that the popular ESPer mayhem series Mob Psycho 100 (published in English by Dark Horse) is from an artist, ONE, who made his name doing similarly lo-fi online work.

Into this scene drops An Invitation from a Crab, a year-one release for the new manga-in-English publisher Denpa, as translated by Ko Ransom. The collection itself is not a small-press item; it was first released in Japanese in 2014 by Hakusensha, the same publisher that handles Berserk, and parts of it appeared beforehand via Rakuen, a mainline comics magazine marketed to women. However, the artist, panpanya, has deep roots in Japanese small- and self-publishing, particularly as it relates to Comitia, a seasonal convention dedicated to original works (as opposed to the fanfiction-heavy tables of the larger Comiket). Considerable domestic acclaim followed the 2013 release of Ashizuri Aquarium, a first-ever arrangement of the artist's theretofore self-published comics, as released by January and July, a book publisher-cum-anime goods merchant; An Invitation from a Crab is thus panpanya's wider-release sophomore collection - a major-label second album, albeit the first to appear in English.

I'm going to use the images above as a sort of synecdoche for panpanya's artistic approach. The talking fish the protagonist hesitates to cut is a blatant cartoon: it's just an oval with a dot and a few lines. But when the fish's whimsical flesh is sliced away, and its funny voice silenced, we see that its guts are realistic, full of tight hatching and solid blacks, as is the room in which the main character stands. That character, however, is themself a cartoon. Later in the story, having completed a day's work of cutting up talking fish, they will return to their apartment and set eyes upon the cartoon fish they keep as a pet in a tank. The fish welcomes them home, and they ask the fish if it too is just appealing to human emotions for survival: "Are they just words to you too?" The fish replies, in human speech, that yes, they are just words.

The protagonist in each of the 18 comics collected in An Invitation from a Crab is always the same: an unnamed character with shoulder-length hair, of variable age, with no specified gender (at least, not in translation). Sometimes the character is an adult, living with a partner. Sometimes the character is a school student - sometimes wearing a skirt, sometimes wearing trousers. But they always look exactly the same, which is an old manga trait: if we know nothing else, we know of Osamu Tezuka's tendency to 'cast' the same character designs over and over as different characters. Similarly, this very cartooned figure, with their Harold Gray circle eyes and three-or-four-vertical-line bangs, is frequently set against backgrounds as intensely worked-over as anything from the heyday of the Shigeru Mizuki studio. But panpanya is not doing this merely as a gesture toward tradition; rather, the drive of their art -- the publisher employs gender-neutral pronouns when referring to the artist, and I will follow suit -- is the shifts in perception native to any individual's observation of the world around them: the person, and their environment, as separate and mutable beings, therefore drawn distinctly by the artist.

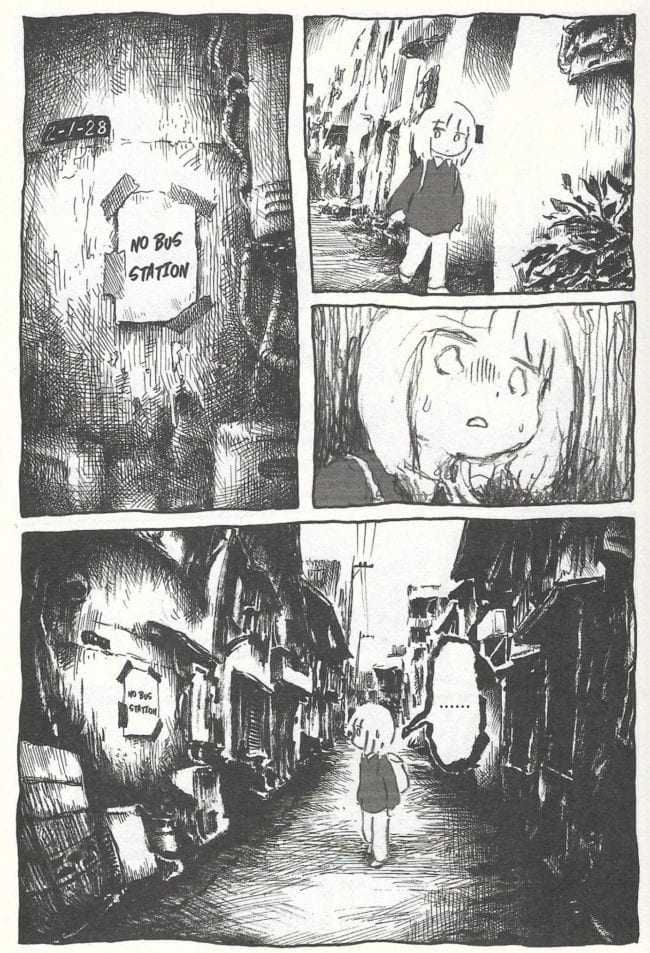

The above image is from "Wandering, Wondering", one of the longer stories in the book, in which panpanya draws the main character in pencil, and composits them against ink backgrounds, so that they seem to dimly glow. (As evidenced by this interview, panpanya's self-published works employed further, hand-fashioned tactile techniques, which could not transition to mass-production comics.) The story, appropriately enough, is a tale of supernatural displacement, finding the character woken from a nap and exiting their train at the wrong stop, only to discover that they've been startled out of their body, and are now a ghost wandering unfamiliar streets. Several minor adventures occur, in which companions are met and quests completed, until order is restored. Later, the protagonist, in the waking world, passes by the same stop on the train, but feels no desire to exit to a place where they are not going.

This is less a folktale than a daydream; an adventure intuited from gazing upon fast-passing places on a late afternoon commute. Every so often, the comics in this book are separated by short, LiveJournalesque text pieces, in which panpanya ponders questions of observation: rain falls from clouds as drops, but we perceive it as lines, and if a thousand frames of movement could be compressed into one second of perception, wouldn't a rational phenomenon like that be ascertained as magic? Or: to observe an airplane in the sky at night is to understand that its blinking light represents dozens of human lives, and that the lights seen from the plane are similar abstractions of human activity, seen as still images but understood to represent lives and movement. Right?

These are not revelatory pieces of writing, but they illustrate the concerns of panpanya's comics, which intuit low-key mythologies to enliven simple quirks of observation. If the lead character cannot remember how pineapples are grown, for example, you can be sure a journey will result, in which seemingly nobody in Japan knows the answer, though some have constructed elaborate industrial workarounds for their natural ignorance. These whimsies are sometimes presented as explicit recollections of dreams, and sometimes they become melancholic allegories. One of the best of the very short stories, the five-page "Incomprehensible Memories", has the protagonist recall several visits with their grandmother, in which their grandmother would always present them with a toy. Year after year, the toys grow increasingly complex, their mechanisms obscure, so that the maturing protagonist is alienated from these affections. Finally, the grandmother dies, and the protagonist finds a letter addressed to them, but the calligraphy in the letter is too complex for them to read; they wonder if they will ever grow to the point where they understand what this older person has been telling them.

The drawing is very good throughout; panpanya apparently works from memory sometimes in doing the backgrounds, and I can't tell which images are drawn from memory and which are drawn from photographs, as all of their images are very lively and emphatic, giving a rare sense of subjectivity to the narrow streets and stacked housing familiar to readers of urban manga. This is important, because sometimes the drawing has to hold the reader's interest as the artist's narrative concerns lead them into preciousness. Another of the longer stories sees the protagonist so obsessed with preparing themselves for a day off, they wind up preparing right through the day and missing all the fun; this sort of plot does sync up with panpanya's thematic concerns, but I'm certain I've seen it done multiple times in children's entertainment, and what keeps my adult attention from fleeing at the prospect of 30 pages of that is not the artist's entirely straightforward recitation of the message, but a prolonged intermission in which the protagonist wanders through their wobbly neighborhood, which seems to inhale and exhale, tightening into heavy black tree leaves and bicycle silhouettes, then loosening into ballpoint doodles of roofs and tree trunks around steps in a park.

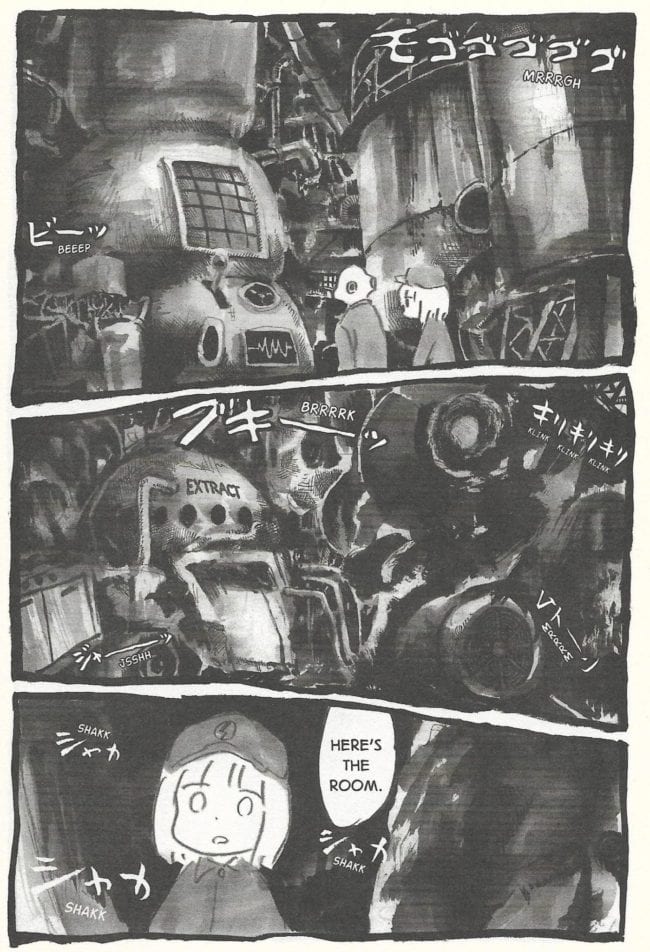

It is not always a kind place. The most striking of the stories, "innovation", hones in sharply on the topic of work. The protagonist never seems to be very well-to-do in An Invitation from a Crab, but here they're an exhausted student laborer in a power plant, where all they do is smash coconuts; their exhaustion is relieved temporarily by drinking sweet coconut juice ("This stuff tastes so good, I almost feel like it's what I'm working for"), but they still wind up sleeping through class. Eventually, a school assignment leads them to devising a means of automating their job so that they can rest a bit, but this only inspires their boss to similarly automate the line, eliminating the protagonist's position and driving them deeper into the ink wash bowels of the plant, where they discover that they were never producing coconut power at all: they were only ever producing the coconut juice, which serves as a stimulant for a massive corps of yet-more-exhausted laborers racing all day on fixed bicycles to power the region. Education is of no help to the protagonist, because their teacher back at school doesn't understand; the educator can only think in theoretical terms about the situation, suggesting more and more fanciful means of powering the world with coconuts as the workers race and race and race.

I don't know the circumstances of panpanya's life. They've released four books with Hakusensha since this one, which is almost one per year; I presume they work on their comics pretty consistently, but you nonetheless get the feeling that this is an artist who still recalls what it's like to work a day job. The perspective is a little different from what you see in so many Japanese comics that present workplaces as a stage for comedy and drama. But panpanya is not a revolutionary; their protagonist is an observer and a consumer, always delighted to return to their normal life. If they are not a conformist, that's no fault of their own. If I were to grasp for a comparison in big-time manga, it would be Taiyō Matsumoto's graphic novel GoGo Monster, in which children reject the absorbing world of imagination to grow up happily among peers in society. The twist panpanya offers is that while life goes on in the waking world, so does life continue in the imaginary, a living place somewhere in the backdrop, where the artist's unchanging hero cannot fully integrate themselves, because there is something... something they see, always, in the corner of their eye.