The latest in a strong and growing catalog from NYRC, William Gropper's Alay-Oop is another important stepping-stone in the development of the graphic novel..

Though the term "graphic novel" didn’t exist until decades later, the concept was pursued by American publishers in the first half of the 20th century, with such artists as Lynn Ward, Milt Gross and Frans Masereel exploring the concept of telling stories in visual form. Like silent films, these graphic narratives didn’t have dialogue. Text, if at all present, is purely for the sake of story information. Ward and Masereel depicted their works in Expressionist woodcuts.

Milt Gross parodied Ward with his 1930 He Done Her Wrong, which he drew in his aggressive, lively scrawl. That year, William Gropper bridged the gap between Gross’ lampoon and Ward’s sometimes-strained seriousness with Alay-Oop. 90 years later, Gropper’s book impresses with its fresh, spontaneous-seeming graphics and its gentler, more reserved dip into the eternal well of the human comedy.

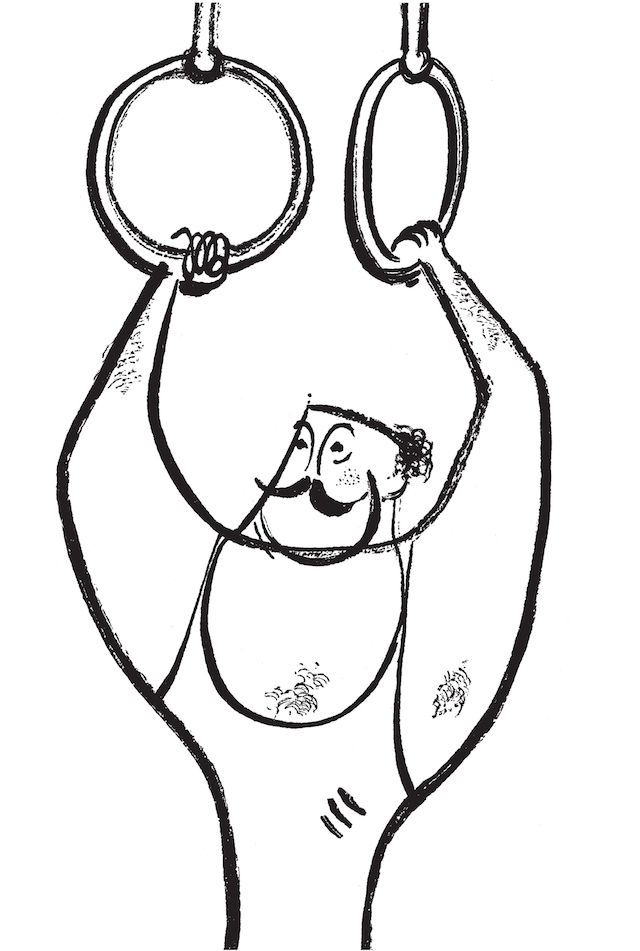

James Sturm provides a concise introduction to Gropper and his work and includes two examples of the artist’s political cartoons of the period. Gropper, like other New York-based cartoonists, was inspired by (and contributed to) the revolutionary changes in graphic design and fine art. Alay-Oop’s first drawing strikes the reader with its bold visual shorthand. A trapeze artist, depicted from the torso up, is reduced to chiseled geometric shapes. The figure’s head is bisected by a bold line that forms the inner side of his arms and shoulders. Fingers are rendered as curlicues. The hairs of Gropper’s brush form double lines in one area. It’s a gentle abstraction of the human form rendered with sureness and daring. Gropper’s figures and their settings invite the reader to make connections and literalize his figural images.

The narrative of Alay-Oop is a familiar love triangle—told well and full of visual detail. The book appears to be a breeze; something you could read on a coffee break. Each image invites—and demands—the reader linger a while. Every stroke of pen and brush counts. The clutter of Gropper’s mise-en-scene tells us much about the lives of his characters. Backgrounds of everyday images distort to suggest a character’s inner self. Dry-brush and splatter work bring texture to the crisp graphics without weighing them down with cross-hatching.

This look would be co-opted by the publishing and advertising world by the 1950s and remains a visual signifier of anything retro. It’s important to recognize that work like this was being done before the first World War and that this approach blossomed between wartimes.

This look would be co-opted by the publishing and advertising world by the 1950s and remains a visual signifier of anything retro. It’s important to recognize that work like this was being done before the first World War and that this approach blossomed between wartimes.

Gropper’s op-ed cartoons appeared in The New Masses, The Liberator and other socialist publications, alongside such openly political artists as Art Young. There is no political affect to Alay-Oop. Though Sturm’s introduction is helpful, the book doesn’t need any qualifiers to sit down and read. It’s a testament to the power of individual images—which are, in this book, isolated to one side of each page, save for a couple of full spreads.

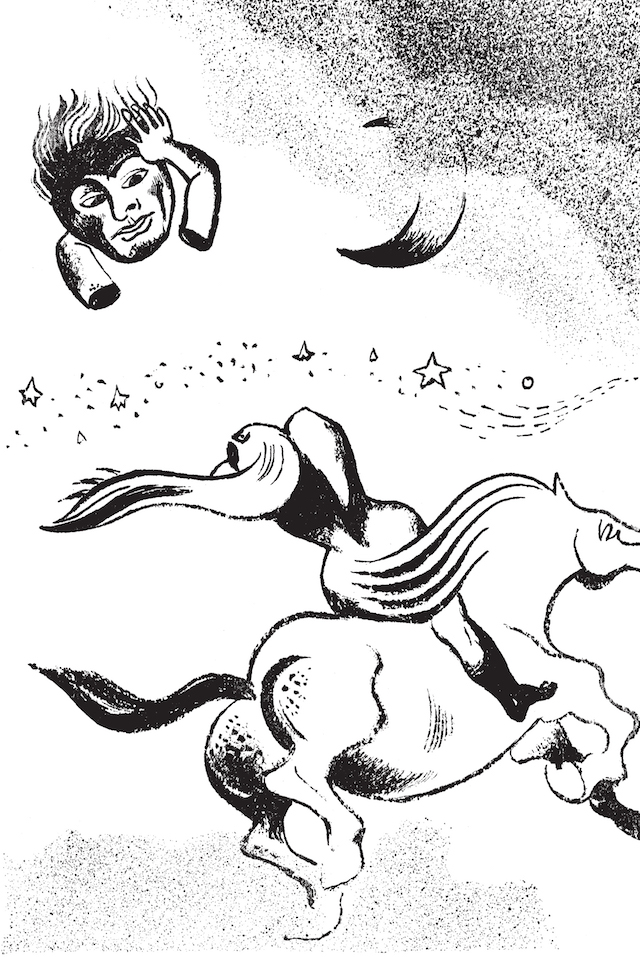

A dream sequence in mid-book provides Alay-Oop’s tour de force. Its images capture the irreal subconscious, and the sense that the dream appears tangible and logical to the dreamer as it occurs. “The Dream” stands on its own as a bold, inspired visual psychodrama and rates as the most intense and inspiring graphic work I’ve seen this year.

A dream sequence in mid-book provides Alay-Oop’s tour de force. Its images capture the irreal subconscious, and the sense that the dream appears tangible and logical to the dreamer as it occurs. “The Dream” stands on its own as a bold, inspired visual psychodrama and rates as the most intense and inspiring graphic work I’ve seen this year.

Handsomely mounted, with a superb cover design by Sammy Harkam, Alay-Oop is no period piece. Its graphics and narrative are timeless and remind us of the liberation from rote representation that cartooning offers all artists.