Denis Kitchen, whose Kitchen Sink Press published compilations of Al Capp’s Li’l Abner dailies from 1934 through 1961 in 27 volumes (1988-1998), had developed a rapport with Capp’s family, widow and children, that gave him extraordinary access to Capp’s papers—letters, documents (including two unpublished autobiographies) and memorabilia that the Capp family had in storage boxes. As the authors say in their Acknowledgements: “We spent countless hours constructing timelines, checking and corroborating the facts, reading through thousands of pages of news clippings, letters, and official documents; we watched old recordings of his television appearances. We interviewed, in person, over the phone and via 3-mail, anyone who could supply us with needed information and details.” The result is this remarkable biography, rich in the details of the major events in Capp’s life.

Before we plunge further into this review, I should alert you to the biases I bear that may affect my opinion of the book. Kitchen has been acting as my agent for several years in an effort to find a publisher for my own Capp book, Hubris and Chutzpah, about the sensational feud between Capp and Ham Fisher, creator of Joe Palooka, a strip equal to Li’l Abner in popularity but entirely different in its themes. Despite many years of trying, Kitchen has been unable to find a publisher, and so I’ve published the book myself, posting it to my website, RCHarvey.com (in the Hindsight department) just about the time the Schumacher-Kitchen book came out. So my biases, however discernible they may be, spring, on the one hand, from a long and friendly relationship with Kitchen; on the other hand, from his failure to find a publisher for my book. (To be fair, I wasn’t pushing him very hard at any time because I was always so deeply into other projects I could not have spared much time to do the book even if he’d found a publisher. I don’t think I’m at all miffed about this, but maybe I am and don’t know it.)

Then there’s the fact of my book co-existing with theirs. “Natcherly” (as Li’l Abner would say), my book is better; theirs, perforce, must not be as good. Or so it would seem. (But my book focuses on only one aspect of Capp’s protean life; theirs, on many for facets of that life. And besides, theirs is very good indeed.)

Having now raked up all the scruples I can think of, we can dash headlong into a review. Whether these confessed biases influence my attitudes about the Schumacher-Kitchen book for the better or for the worse you must decide for yourself as you plow through the review that ensues.

The chief occurrences of Capp’s life are treated in great detail: the loss of his left leg at the age of nine and the probable psychological consequences; his education at a succession of art schools he was too poor to pay tuition to; his apprenticeship to Ham Fisher and the dispute about who created the hillbilly Big Leviticus in Joe Palooka; the resulting feud, its nastiness, and Fisher’s attempt to smear Capp’s reputation; Capp’s emergence as a pop culture celebrity; his shrill attacks on the New Student Left on college campuses; his notorious visit to John Lennon and Yoko Ono; the subliminal eroticism in Li’l Abner; Capp’s extracurricular sex life, preying upon show girls and college co-eds, and his fall from grace as a result. In every instance, the book offers insights into these events that are new to me (and I’ve researched Capp’s life for my book, at least as much as publicly available documents permit).

The chief occurrences of Capp’s life are treated in great detail: the loss of his left leg at the age of nine and the probable psychological consequences; his education at a succession of art schools he was too poor to pay tuition to; his apprenticeship to Ham Fisher and the dispute about who created the hillbilly Big Leviticus in Joe Palooka; the resulting feud, its nastiness, and Fisher’s attempt to smear Capp’s reputation; Capp’s emergence as a pop culture celebrity; his shrill attacks on the New Student Left on college campuses; his notorious visit to John Lennon and Yoko Ono; the subliminal eroticism in Li’l Abner; Capp’s extracurricular sex life, preying upon show girls and college co-eds, and his fall from grace as a result. In every instance, the book offers insights into these events that are new to me (and I’ve researched Capp’s life for my book, at least as much as publicly available documents permit).

About Capp’s womanizing, for instance, I learned that for over a year (1940-41) he conducted an affair with a young singer in California. The book quotes from her letters to him (found, I assume, among Capp’s papers) and, remarkably, from his letters to her, obtained from the daughter of the woman in question. This was no simple dalliance: they were obviously in love. The authors also interviewed Patricia Harry, the University of Wisconsin co-ed whose misadventure with Capp became national news when she sued him. Her detailed account of the rape is chilling and disgusting—and entirely new; until reading it, I had assumed, with the rest of the world, that the charges against Capp were all about his attempts (attempted adultery and attempted sodomy [oral sex]) rather than his debatable “success” in sexually assaulting her.

About Capp’s womanizing, for instance, I learned that for over a year (1940-41) he conducted an affair with a young singer in California. The book quotes from her letters to him (found, I assume, among Capp’s papers) and, remarkably, from his letters to her, obtained from the daughter of the woman in question. This was no simple dalliance: they were obviously in love. The authors also interviewed Patricia Harry, the University of Wisconsin co-ed whose misadventure with Capp became national news when she sued him. Her detailed account of the rape is chilling and disgusting—and entirely new; until reading it, I had assumed, with the rest of the world, that the charges against Capp were all about his attempts (attempted adultery and attempted sodomy [oral sex]) rather than his debatable “success” in sexually assaulting her.

With the detail of these two revelations in mind, it is remarkable that the authors’ treatment of the erotic images in Li’l Abner is so restrained. Fisher accused Capp of making pornography, and one of the issues raised by the accusation was whether Capp had drawn the pictures in question. Capp denied it. And his friends in the National Cartoonists Society (including Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff) supported him in his denial. Wikipedia asserts that the dirty pictures are forged. Not so. Capp did, indeed, draw the pictures; and in my book, I provide visual evidence to support this contention.

Schumacher and Kitchen agree that Capp drew the offending pictures albeit their assertion is considerably more circumspect than mine: “For discerning readers, including Fisher, Capp’s frequent visual and verbal double entendres were indisputable, but they were always clever enough to be ambiguous and thus fly below the radar of the vast majority of unassuming readers.” In support of this view, they reprint a couple of the tamer specimens, both of which I’ve included in my book. I also include many others, most of which are much more blatant comedic examples of sexual imagery in the strip, albeit still equivocal and subject to alternative interpretation. Clever, as they say.

Schumacher and Kitchen navigate their way through the porn episode by focusing mostly on the second issue that Fisher’s accusation raised: was he the person who circulated carefully cropped panels from the Li’l Abner strip to newspaper editors, claiming the pictures showed that Capp was a pornographer and urging that the editors therefore drop the strip? And did Fisher send those same images in 1951 to a New York state legislative committee investigating comics? By this indirection, Schumacher and Kitchen avoid dealing at length with the more scandalous aspect of the affair—namely, that Capp was producing subliminal pornography. My answer, as I’ve said, is that he most assuredly was. That’s their answer, too, but circumspectly stated, as we’ve seen.

As for Fisher’s hand in the affair, Schumacher and Kitchen decide, as I have, that Fisher did smear Capp by circulating the incriminating pictures. The National Cartoonists Society reached the same conclusion and suspended Fisher for conduct unbecoming of a member. At the time, with Fredric Wertham blathering on about comic books turning children into blood-thirsty criminals or drooling sex maniacs, Fisher’s distributing nasty pictures purportedly being drawn in a daily newspaper comic strip threatened all syndicated cartoonists as well as comic book publishers. Fisher, humiliated by the suspension, could no longer go out in public, visiting fashionable night spots to play the role essential to his ego—that of the cartoonist celebrity. Within a year, he’d committed suicide.

An explanation for the gingerly way the authors deal with Capp’s career as a pornographic prankster may be that the Capp family—his widow, daughter, and grandchildren—didn’t want this dirty linen aired, and since Schumacher and Kitchen depended upon their help (giving access to Capp’s papers and being interviewed), the authors may have been reluctant, understandably, to upset their sources. Kitchen explained in an interview with Michael Dooley at imprint.printmag.com:

I’m afraid there were a good number of things that key members of his family resisted having us include. In some cases, out of genuine respect for their feelings, we truncated excerpts from letters—in particular, a discarded suicide note—because Capp’s invective was so bitter and personal. We also agreed, for example, to eliminate a raunchy story that Frank Frazetta once related to me. In some cases, the evidence for certain alleged events was not enough for us to be comfortable stating as fact, so such elements didn’t make the cut for evidentiary reasons. But in most cases, we included fact-based controversial material over their objection.

“I’ve known the family for years,” Kitchen continued, “and felt we had become friends. So when I started this biography, I assured them that we were very serious and that it would be a ‘warts and all’ biography. To their credit, they cooperated fully and provided access to most of the surviving papers and correspondence. But I don’t think they realized what other people had on Capp. When they finally read our draft manuscript, they made it clear they were hoping we downplayed his dark side and portrayed the later years more sympathetically.”

But Schumacher and Kitchen persisted and were finally given permission to use even copyrighted material without any conditions except for including a disclaimer on the book’s copyright page:

“Neither Capp Enterprises, Inc., nor any affiliates, including members of the family of Al Capp, attests to the accuracy of any statements, facts, or conclusions set forth by the authors. Capp Enterprises, Inc., in no way endorses the content of the book nor does it imply that the book is in any way an authorized biography of Al Capp.”

Pretty severe, you’d think; but, given some of Capp’s adventures related therein, the disclaimer amounts to a ringing affirmation of the book’s accuracy. The essence of all of Capp’s career, if not in every sordid detail (but in detail enough), is here, at long last.

Schumacher and Kitchen have squelched rumor and hearsay with reasoned argument and persuasive fact. The result is a genuinely impressive and authoritative insight into an overlooked but morbidly fascinating corner of comics history.

Their resolution of the hillbilly dispute that prompted the Capp-Fisher feud is similarly satisfying. They credit both Capp and Fisher with aspects of the creation of Big Leviticus while also concluding the Capp’s version of the story is probably more fiction than fact—something that was often true of Capp’s accounts of events in his life.

In their Big Leviticus scenario, Schumacher and Kitchen endorse both sides of the debate by knitting a few known facts together with a few reasonable speculations and adding some probably fictional connective tissue to create a cohesive story. In their conclusion, they decide for Fisher. They suppose that Capp brought the idea of hillbillies to story conferences with Fisher, and Fisher, even though not initially keen about using such characters, wrote a script for the Big Leviticus adventure. In support of this contention, the biographers cite a long-standing custom in the syndicate business that cartoonists submit scripts to their syndicates for approval 6-8 weeks before scheduled publication.

This interpretation of events is as plausible as any other. But the explanation is scarcely leak-proof. Not all syndicated comic strip cartoonists were required forever by their syndicates to submit scripts for approval in advance. And by 1933, Fisher’s strip was roaringly successful; it’s at least probable that he wouldn’t have been expected to get approval in advance for his stories. Moreover, in support of Capp’s version of events, Big Leviticus’ behavior is more akin to the sort of comedy Capp would later develop in Li’l Abner than anything Fisher had done or would do.

Still, Schumacher and Kitchen find it highly unlikely that Fisher, a notoriously fussy man, would have permitted his “brand new assistant” to solo on the Big Leviticus story so soon after joining Fisher; the Big Leviticus story appeared in late October, and Capp had joined Fisher only five or six months earlier.

Schumacher is the chief writer of the book; Kitchen, the researcher and fact-checker. “After decades of seeking,” Kitchen told me, “I had amassed a full file cabinet, several binders and about six storage boxes of newspaper, magazine articles, interviews, photos, clippings, correspondence, an unpublished autobiography, and ephemera of all kinds. And I had been talking to [Capp’s] associates and relatives for years. That was my primary contribution. Once we agreed to co-author, we divvied up the new interviews and shared everything. And Michael is the more experienced writer, so he did all the first drafts, then we’d go back and forth until we were both happy.”

Schumacher’s narrative manner is novelistic. He often says what Capp and others “thought” or “suspected” or “hoped.,” creating a mildly annoying nag at the back of the scholarly reader’s brain. Clearly, he cannot know what these people were thinking or what they suspected. But he is a thorough-going professional and he works within the biographers tradition, speculating reasonably from the evidence of letters and interviews and the like. And his style, brisk and confident, persuades me that he knows what he’s talking about even when he seems, impossibly, to be inside the heads of his subjects.

Despite such quibbles, I enjoyed the book immensely, and I learned many things I never knew. The authors go into some detail in describing the functioning of Capp Enterprises, for instance—the entity Capp established to merchandise his creations. Several sections of the book reveal the seemingly endless quarreling between Capp and his brother Bence, the chief operating officer of Capp Enterprises.

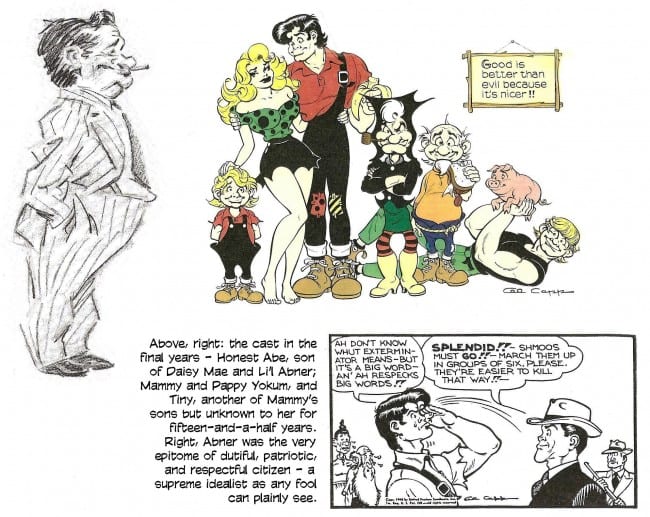

The book offers details about Capp’s family life, his love for his wife and children, and his business practices and publicity schemes, his toying with running against Ted Kennedy for a Senate seat, his tv show and guest appearances on talk shows, the creation of the Broadway musical “Li’l Abner” and the movie version thereof, a Fearless Fosdick tv puppet show that failed.

Throughout, tantalizing tid-bits are dangled. Capp and his assistants talked “Dogpatch lingo” in the studio. Capp’s early sketches for the Kigmy, a successor to the shmoo that encouraged irrate people to kick it to relieve their rage, was at first a much more overtly satirical character: it had a dark-skinned face with a prominent nose—visual shorthand for African Americans and Jews, two minorities often kicked around. There was a Fearless Fosdick tv puppet show that failed.

There are occasional lapses in accuracy albeit nothing major. Capp was awarded the NCS trophy as Cartoonist of the Year in 1948, not 1947; the award was for his achievement in 1947 and therefore carries that date, but it was actually given in the spring of 1948. A minor matter, surely, but the authors hinge this event to another—the first of a two-part profile of Capp in The New Yorker that began in November 1947, implying that the conferring of the award prompted the article. Impossible.

Another minuscule quibble: the Fisher legend is that he went on the road himself to sell Joe Palooka. Schumacher and Kitchen say this occurred in 1928, implying that the strip started about then; but Joe Palooka didn’t begin until 1930, April 21.

The book portrays Milton Caniff as buying whole-heartedly into Capp’s contention that his sexual assault of a co-ed in Wisconsin was a frame-up by angry lefty students. True but not quite. Caniff was quite aware of his friend’s sexual proclivities. Although out of loyalty and friendship, Caniff contended that Capp had been the victim in the incident, at the very same time, he strongly suspected that Capp was guilty as charged. Capp’s mistake, Caniff believed, had been in approaching “amateurs.”

“Al was down in New York every week and sometimes for weeks at a time, having his fun,” he told me. “He had some good lookin’ broads, believe me. They all flocked to him, thinking that he could do them some good in their careers. He seldom got caught because he didn’t have anything to do with amateurs: the women he squired around town here were obviously gals on the make—showgirl types, gals who wanted to be seen with celebrities. The old badger game he fell into in Wisconsin could have happened only in a place like Wisconsin—not around New York City.

“Al had a strangely naive attitude about himself,” Caniff went on. “He thought he could come down here to New York and play around with these babes and no one would say anything. Once when a gossip column mentioned his being seen with Miss Hootenanny or some such, he was shocked. He thought the ‘boys’ would protect him. He thought the Winchells and all the others would—out of professional courtesy—not mention anything. But those guys would turn on their own mothers. So it got to be sticky: [his wife] Catherine also read the papers. Everyone just kind of avoided the subject.”

In 1947, Capp famously sued his syndicate, United Feature—for $14 million. But we never learn what, exactly, was the outcome. A “favorable resolution” was reached, Schumacher and Kitchen tell us, but what that was, exactly, we never learn. My guess, based upon other sources, is that part of the resolution was that Capp was promised eventual ownership of the strip. And in 1964, just after he acquired ownership, he took Li’l Abner to another syndicate, the Chicago Tribune-Daily News, where he negotiated an even better deal.

At least one other tid-bit the authors bring up but leave dangling. They mention the name Nancy O., which Capp began dropping, unexplained, into corners of the strip in the fall of 1948. The mystery he was creating “continued, unbelievably enough, until May 1951"—when it was, presumably, resolved. But to find the resolution, we must resort to the Notes at the back of the book.

The book is not footnoted but it is thoroughly sourced in the Notes which refer to page numbers in the main text—one of several accepted scholarly practices these days. But sometimes Schumacher and Kitchen do more than simply source their facts: they retail whole anecdotes. In the case of Nancy O., they reveal in the Notes that Li’l Abner fell in love with this mysterious woman with an hourglass figure whose face is never shown. Capp ran a contest to determine what Nancy O. should look like, asking readers to send in photographs of “their sweetest girl.” The winner, a University of Florida student, was depicted in the strip on May 14 and then appeared on the Milton Berle tv show the following evening. In the strip, however, the reason that Abner fell in love with this shapely specimen is that she had the face of his mother; when Nancy O. had plastic surgery done to give her a more youthful, beautiful visage, Abner promptly fell out of love. A typical Capp stunt. But it is consigned to the small print in the back of the book, where only fanatics like me browse.

And buried in another Note is one of the most revealing insights in the book. After mentioning an unpublished autobiography Capp wrote, Kitchen says: “More than forty-five years after he worked for Fisher, Al Capp’s emotions still ran high when he discussed the details of his employment and Fisher’s character. He was becoming so enraged when typing the manuscript that he [hit the keys so hard they] would punch holes in the paper when he was typing lower-case o’s. Entire pages dealing with Fisher are perforated, whereas all the other pages are clean.”

In various places, Schumacher and Kitchen remind us that while Capp was cranky and argumentative and stingy (a typical child of the Depression), he was also generous, surreptitiously giving money to people and causes he thought especially needy or deserving. To the end—even while posing as a rip-snorting conservative—he was essentially liberal: he supported gay rights and “on more than one occasion, stopped someone from telling a gay ‘joke,’ or an anti-black joke.”

His last years were sad. Confined to a wheelchair (unable to walk because emphysema shortened his breath with the slightest exertion), he was sick and delusional, “wrote excoriating letters” to family and friends, fought with his assistants “when they tried to collect money he claimed they didn’t have coming”; he endured mood swings from rage to depression, caused, perhaps, by his being over-medicated. “He could be overheated one minute, tender the next. He still had powerful feelings for his family. ... Capp spoke of wanting to provide for Catherine, ‘to keep her warm.’ ... ‘She deserved a better life.’”

When he dies November 5, 1979—exactly two years after the last daily Li’l Abner strip was published (pictured here)—on page 261 of a 263-page text, we are relieved that this contrary man is at last at rest.

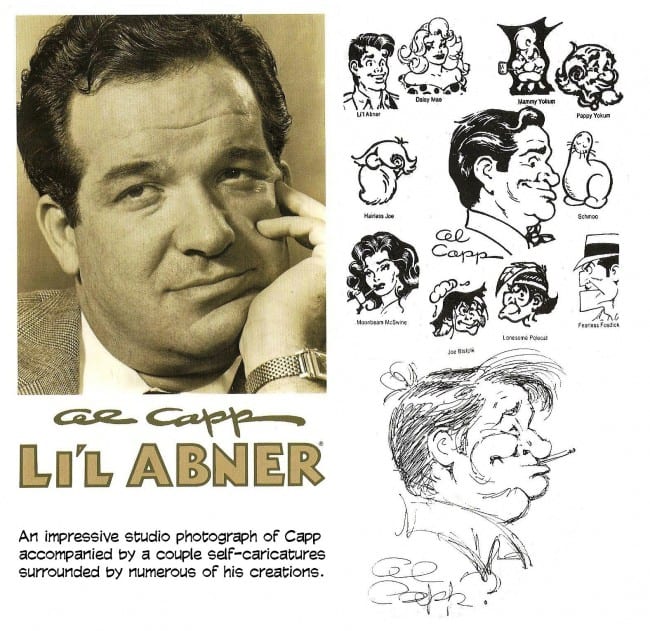

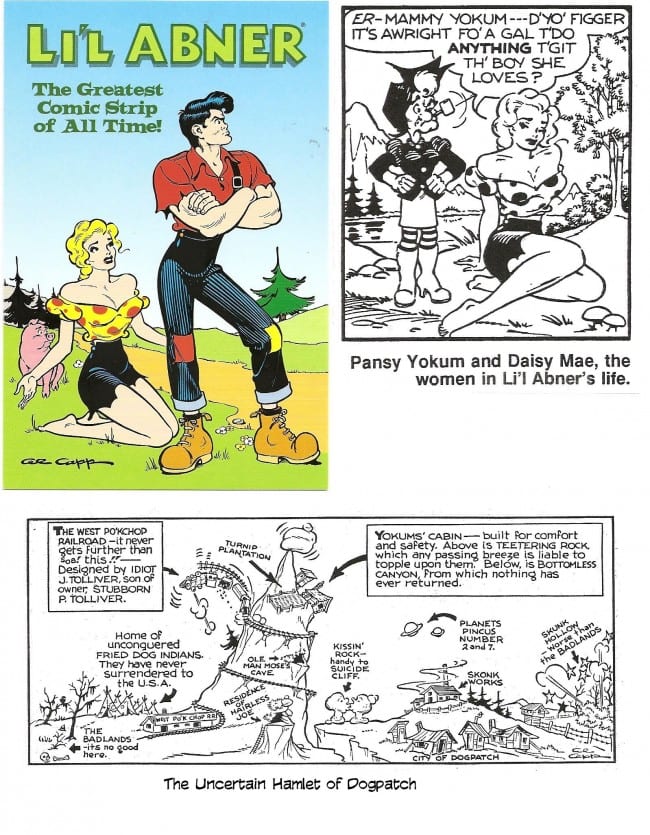

The book is amply but not excessively illustrated with photographs and a dozen or so Li’l Abner strips. The authors mention and discuss most (if not all) of the fondly recalled of the strip’s lore—Sadie Hawkins Day, the shmoo, Lower Slobbovia, Fearless Fosdick, and the like. But, strangely, there is little or no analysis of the strip as pervasive satire.

The shmoos, for example, supply humans with food and loving companionship and are therefore a threat to so-called civilization: humanity loses the motivation to go to war and to engage in every sort of capitalistic enterprise. Why bother? Shmoos provide everything one needs. And for that very reason, in Capp’s satirically warped mind, the shmoos had to be destroyed wholesale. Otherwise, they would “corrupt” society, demolishing the very things upon which civilization is founded—namely, greed and need.

And Lower Slobbovia, Capp’s satire about U.S. foreign aid, is similarly slighted; the authors mention this miserably poor “country” only in connection with the Lena the Hyena contest to draw the world’s ugliest woman.

At first blush, the absence of any discussion of Capp’s satirical genius seems a colossal oversight. Li’l Abner was the first overtly and doggedly satirical comic strip in syndication, breaking long-standing taboos in the industry by espousing and proclaiming a point-of-view on social and political matters usually left safely off camera, and Capp achieved fame outside the strip as a satirical commentator of raucous but keen social and political insight. His fame, built upon satire, was so great that he was the only cartoonist other than Walt Disney to have a theme park built upon his creation—Dogpatch, U.S.A.

Capp was one of a handful of genuine trail-blazing newspaper comic strip cartoonists, and he is in the forefront of that small but significant procession. Without any discussion of the workings of Capp’s satire, we can’t have much appreciation for the profound achievements of his career.

In defense of the authors, however, I direct attention to the subtitle of the book: it’s the “Life” not the “Life and Art” of Al Capp. The emphasis is, as predicated by the title, on the cartoonist’s life not on his artistry. And his life was, as his brother once said, at least as interesting—as compelling a narrative—as the fictions Capp told about himself.

Footnits: I NEVER MET CAPP, but I saw him in action once. He was the luncheon speaker at a conclave of college journalists in Chicago in 1958. The Vietnam war was still some years in the future, so Capp had not yet assumed the role of goad with collegiate audiences. As the luncheon crowd assembled, I was standing at the entrance to the ballroom when he and his entourage came down the hall. He didn’t so much limp because of his wooden left leg: he lurched, swaying from side to side as he swung his artificial limb along, transferring his weight from his good leg to his bad and back again in rhythmic alternation.

After lunch, he did three things that have stuck in my memory. He was seated at a raised head table with various dignitaries of the conference, and I was at a table nearby, so I could see him clearly. When he’d finished eating and just before he was introduced to speak, he dipped his fingers into the goblet of water in front of him and wiped them on his napkin. His drinking water glass was suddenly a finger bowl. Others may have found his maneuver somewhat crass, but I didn’t: I understood, I thought. As a cartoonist myself, I was fairly fastidious about keeping my hands clean because if I didn’t, I risked putting smudges on the drawing paper, blemishes that might be reproduced with the drawing. So I always washed my hands before doing any drawing. It became a habit, then a kind of fixation. And I recognized the same fixation in Capp.

His speech consisted of answering questions from the crowd. One exchange was memorable. A co-ed wearing a tight green sweater stood up, and, alluding to Evil Eye Fleagle in the strip, she asked Capp how to deliver the “double whammy.” He looked at her for only an instant before responding with a grin: “Just keep on wearing that sweater, honey.”

After the laughter subsided somewhat, he gave his quip a second bounce: “If this is what she’s like when she’s green,” he said, “think of what she’ll be like when she’s ripe.”

Ugly sexist comments, no question; but not so far askew for the time.

At the end of his remarks, Capp turned serious. He’d grown up in a succession of ghettos, he said, poor neighborhoods where the kids who played together made a diverse band of juveniles, coming from a variety of ethnicities. He’d sometimes eat at friends’ houses, and they at his. Sometimes the meal was spaghetti and meatballs; sometimes, gefilte fish and motzo ball soup; sometimes, chitlins witih red beans and rice; sometimes, corned beef and cabbage; sometimes, wiener schnitzel. The kids always enjoyed the variety. They were not upset by their differences but instead enjoyed them.

Then came Capp’s punchline: he’d spent his youth trying to escape that neighborhood, Capp said, and he was spending his adulthood trying to get back into it.

It was bullshit, of course; but you have to admire the sentiment in his metaphor.

Ever since, those three things about Capp’s performance at that luncheon defined him in my mind. And as I learned more about Capp, I came to believe that definition was pretty much on the mark.

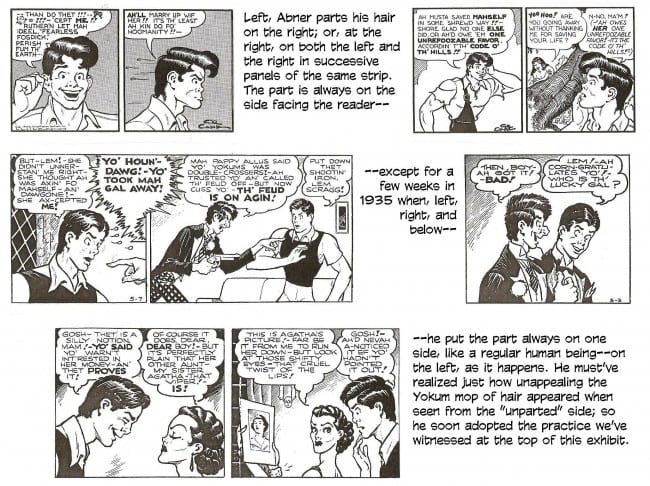

Before we leave Capp, one more historic scrap. You may have noticed, as thousands have, that the part in Li’l Abner’s hair shifted around: first on the right; then on the left. Asked which side his hillbilly bumpkin parted his hair on, Capp usually said, “On the side facing the reader, naturally.” And so it was for over four decades. But before Capp fell into that groove, he experimented, briefly—only four or five times—with Abner having a part on only one side of his coifure. And herewith, we present the evidence.