The philosopher Martin Heidegger once said of Aristotle that his biography should be simple: "He was born. He thought. He died. The rest is anecdote." A similar thing can be said of Ivan Brunetti's new book, Aesthetics: A Memoir. Though there are sprinklings of autobiographical details, they only exist to serve the essence of this book: These are the things that Brunetti made. These are the things that Brunetti finds beautiful. These are the reasons why Brunetti finds them important. It's that simple, which is fitting given that the artist has spent the past decade simplifying his style to a purely geometric set of doodles and squiggles. The book came out of his gallery retrospective show of the same name, giving new life to the "memoir" gag. A gallery show is no place for what we think of as a memoir, but this book that provides precious little of the anecdotes that we associate with autobiography defies expectations in a different way.

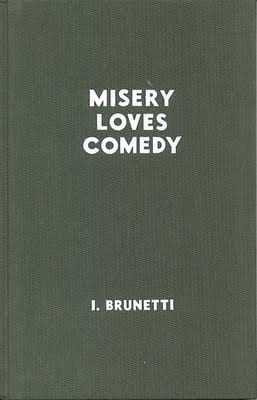

I've been reading Brunetti's comics for over twenty years. I still have copies of Biff Bam Pow!, his anthology series that included comics from a number of Chicagoans. Brunetti's ability as a gag man stood out even then, but I wasn't prepared for the onslaught that was Schizo when I bought the first two issues from him at SPX '97. As a draftsman, Brunetti could do anything, and one could sense him cycling through a number of different styles before settling on something he might be comfortable with. Beyond his impressive technical skill was his envelope-pushing sense of humor that was an assault on propriety and society but especially himself. There have been any number of vicious gross-out cartoonists that have followed in his wake, but both Brunetti's intelligence and the lengths he went to while attacking his own inadequacies as a human being made him unique. Indeed, those early issues were an attack and a judgment on the entire human race, and he didn't leave himself out of that punishment. The fact that he was both eloquent and hilarious in enumerating the ways he hated everyone but especially himself, mixed in with pitch-black gag cartoons that included every form of mutilation, rape, and murder imaginable, made Schizo (the first three issues were collected by Fantagraphics in Misery Loves Comedy) an unforgettable achievement.

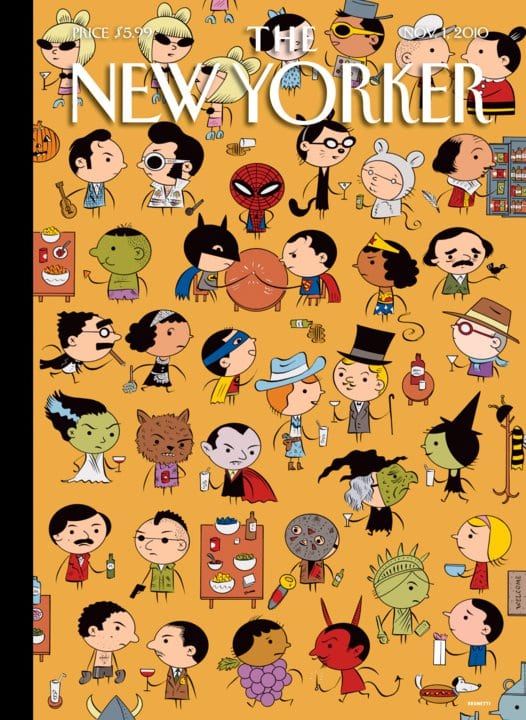

That kind of bile is not sustainable, however. In Aesthetics, he frequently alludes to battles with depression that often robbed him of the desire and inspiration to draw. Indeed, Aesthetics reveals that Brunetti's cartooning output has almost trickled to a halt over the past decade. Most of his work has gone unseen by the comics-reading public, confined to the occasional anthology or issue of The New Yorker. His style underwent a radical change as he boiled his figures down to simple geometric shapes: circles, squares, triangles. He took his influence from Charles Schulz—and Chris Ware, who was experimenting with a similar kind of drawing at the time. This can be seen in Schizo #4 and Ho!, a collection of deranged, hilarious, and repugnant single-panel gag cartoons. Brunetti notes that he feels this current style is about to run its course, but he can't foresee what might follow it (if anything).

That kind of bile is not sustainable, however. In Aesthetics, he frequently alludes to battles with depression that often robbed him of the desire and inspiration to draw. Indeed, Aesthetics reveals that Brunetti's cartooning output has almost trickled to a halt over the past decade. Most of his work has gone unseen by the comics-reading public, confined to the occasional anthology or issue of The New Yorker. His style underwent a radical change as he boiled his figures down to simple geometric shapes: circles, squares, triangles. He took his influence from Charles Schulz—and Chris Ware, who was experimenting with a similar kind of drawing at the time. This can be seen in Schizo #4 and Ho!, a collection of deranged, hilarious, and repugnant single-panel gag cartoons. Brunetti notes that he feels this current style is about to run its course, but he can't foresee what might follow it (if anything).

The contents of Aesthetics reflect an artist and person whose harsher edges have been smoothed away. Simply put, contextualizing his own cartoons within the framework of his own personal sketchbooks, collections of toys and art objects and sculptures, & other art projects allows him to enjoy and appreciate all of it. From a depressed person filled with self-loathing, this is an impressive feat, but there are additional layers to this book that are more in line with his current profession of teacher. Brunetti reveals that since he became a full-time teacher in 2008 at Columbia College Chicago as well of the University of Chicago, his ability to focus on making comics has greatly diminished. There have been exceptions, such as the revealing Kramers Ergot strip that poignantly but hilariously revealed that he has diabetes, but Brunetti simply hasn't been working toward another "real" book of late. Part of the problem, he notes, is that the diabetes has greatly affected his eyesight. He notes that he's going by feel in a number of his recent pieces.

The cover of the book features caricatures of people and characters who Brunetti loves, from the Beatles to the Three Stooges to Chris Ware, R.Crumb, Snoopy, and Puss in Boots. When one pulls off the dust cover, there's a delightful sight gag of a photo of Brunetti working at a tiny drawing board that continues to speak to the lighthearted nature of this "memoir." Every page and every image is deliberately and carefully chosen, because since Brunetti became an educator, every subsequent project of his has had a very subtle pedagogical stamp. Brunetti has always been a deep thinker as a cartoonist, but his ability to articulate what he knows in a manner that is both inspiring and instructive has given this phase of his career an even more impressive impact than his earlier years doing comics.

Take the two comics anthologies he edited for Yale University Press. They were arranged and edited in such a way as to illuminate different storytelling structures and themes without explicitly spelling that out. The same is true of his seminal Cartooning book, an educational manual that is heavier on theory and nuance than it is on prescribed lessons. Brunetti wants to subtly and gently guide his readers through a very specific set of images and ideas but doesn't want to lead them by the nose to do so. Aesthetics does precisely the same thing, only in a unintuitive manner. After a dizzying set of photos of objects and drawings that delight him, the book proper begins with Brunetti's self-bound sketchbooks, scrapbooks, "doodles", "fragments", etc. This is after an inspiring introduction where Brunetti reveals that he's "happy to be a subatomic particle whizzing around the seemingly infinite ocean of cartooning." It's an attitude that undoubtedly allows Brunetti to deal with Lynda Barry's dreaded "two questions" ("Is this good?" "Does this suck?").

From there, Brunetti takes us through New Yorker covers, art projects he made as gifts (the ones he did for his wife are especially terrific), strips published for anthologies and tidbits related to their publication, and "penance exercises," wherein he draws the same character a thousand times. In his commentary, Brunetti reveals the formal intent behind some of his work. For example, he designed his Kramers Ergot strip such that the reader would be forced to turn the oversized and unwieldy book 180 degrees, an exercise designed to reflect the difficulty of his own trials as well as a sort of practical joke on the reader. As the book proceeds, we get an even more intimate look at Brunetti's private projects, like an astounding, tiny sculpture called "The Artist In His Studio", which features a miniature Brunetti shying away from the public. This was done during a depressive period, of course.

Some of the last drawings Brunetti shows the reader are from his childhood. They represent a period of drawing that mixes both intense interest and detail and a total lack of self-consciousness; in other words, the height of play for a child. Brunetti has been trying to duplicate that powerful combination of spontaneity and technique ever since, though that pursuit is effectively chasing one's own tail. Brunetti is trapped by his own perspective as an adult, unable to fully and fairly evaluate his own drawings because of the baggage life brings to every moment one is alive, even when doing something pleasurable like drawing. Even if drawing is more intuitive in some ways than language (which is not suitable to the task of getting across one's ideas), the meanings we give to drawings limit them. I think this is a reason why Brunetti does abstract work and dioramas that resemble Cornell boxes along with more conventional narratives: as a way of guiding himself out of the traps and pitfalls of language.

Some of the last drawings Brunetti shows the reader are from his childhood. They represent a period of drawing that mixes both intense interest and detail and a total lack of self-consciousness; in other words, the height of play for a child. Brunetti has been trying to duplicate that powerful combination of spontaneity and technique ever since, though that pursuit is effectively chasing one's own tail. Brunetti is trapped by his own perspective as an adult, unable to fully and fairly evaluate his own drawings because of the baggage life brings to every moment one is alive, even when doing something pleasurable like drawing. Even if drawing is more intuitive in some ways than language (which is not suitable to the task of getting across one's ideas), the meanings we give to drawings limit them. I think this is a reason why Brunetti does abstract work and dioramas that resemble Cornell boxes along with more conventional narratives: as a way of guiding himself out of the traps and pitfalls of language.

That said, Brunetti offers up some unintentional aphorisms while talking about his own work. After printing a page from his college comic strip, he writes, "Never stop drawing. It is hard to start again if you stop. Drawing is a bicycle, not a car. Life will conspire against you, as complications inevitably pile atop responsibilities. Time is remorseless. Because our culture has a surfeit of artists, it is difficult to succeed; one often has to work against a multitude of obstacles and unfavorable circumstances. Perseverance is much more important than confidence or talent." Sometimes, his advice is that plain because the most important advice has to be clear enough for all to grasp it. Brunetti is quite aware of the circumstances that shaped his lack of self-confidence and depression and grapples with them quite openly in discussing a few of these pieces. And when I say grapple, this isn't just another cartoonist bitching about a lack of inspiration. He's actively engaging his own insecurities and illnesses (both mental and physical) and is always either creating, teaching, or both.

I would argue that in its own way, Aesthetics is a textbook in much the same way that his anthologies were texts. It's a text more akin to Lynda Barry's What It Is than his own Cartooning handbook, as it's about being able to delight in the beauty of the image as well as our ability to create: to draw, to paint, to build models, to sculpt, to arrange colored paper on a page, to craft gags, to make gifts, to think about adding beauty or humor or pathos to a debased world. Aesthetics is a memoir not because he talks about personal details or because it's a catalog of his selected works; instead, it's a testimonial as to why he even bothers to work. It's a statement of purpose. The reader (and potential student of art) is led along through Brunetti's process and history as a way to get them thinking about what delights them and what moves them to think about and seek out beauty in their own lives. As great as Brunetti is as a cartoonist, he's an even better teacher.