"Catelyn! What are you doing?" Lord Eddard Stark asks his wife. "Lighting a fire," she replies on the other side of the panel. In that panel she is putting on a robe.

Nothing I could come up with on my own would better communicate the clumsiness of this well-intentioned but nevertheless egregious misfire of a comic. Adapted from the zeitgeist-bestriding revisionist-epic fantasy novel by George R.R. Martin, who receives top billing on the cover (arguably sole billing, unless your bennies include a terrific vision plan), its creators grab details of description and dialogue from the source material and deposit them in great heaps on every page, yet have no grasp of how to make them cohere, or what made anyone care about the material from which they've been plucked in the first place.

Problem number one is artist Tommy Patterson. It's telling, I think, that in the copious making-of materials that round out the collection, editor Anne Groell (who oversees Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series in its prose form as well) cites cost and punctuality as the first two criteria the team looked for in an artist. I can't really speak to either of those, but man is Patterson wrong for this material.

When compared to its sub-Tolkien high-fantasy peers, the off-model nature of A Game of Thrones the novel constitutes its primary appeal. There are knights and queens and prophecies and dragons (eventually), yes, and neither Martin nor his audience deny their many pleasures. But they're the icing, not the cake. Martin's characters curse and fuck, his wars destroy the fabric of society, his feudalism's institutionalized misogyny and class warfare is foregrounded, his heroes die in failure and ignominy. Yet at the same time, Martin's facility with long-game plotting, and his characters' repeated reminiscences of a romanticized past that they've not only lost but likely never really had in the first place, help the book retain that classic epic-fantasy sense that you've stumbled into something grander and stranger and sadder and more sweeping than the sordid business of revisionist swordplay would indicate at first glance. The fine HBO series based on the books is both more focused and more blunt out of logistical necessity, but smart casting, high production values, and writing with an admirable focus on emotional violence maintains the books' feeling that hey, this is different.

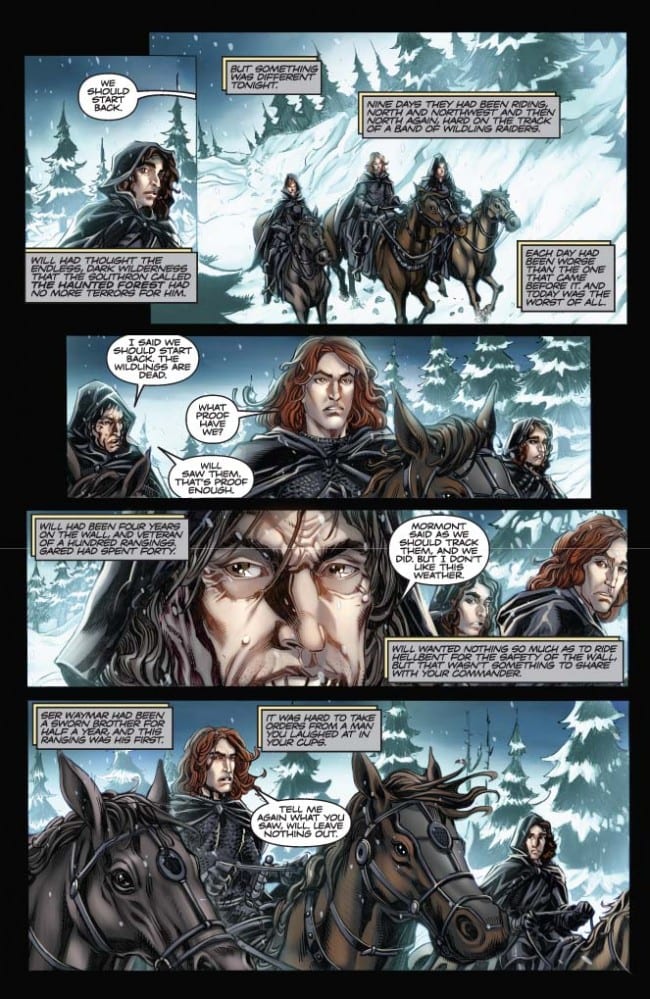

By contrast, Patterson's just more of the mainstream North American comic-book industry same. Heroic figures are his stock in trade, and stock they are: The opening sequence, involving a grizzled old veteran, a seasoned young poacher, and a snobbish teenage lord out on a hunt for barbaric wildlings, looks like Patterson drew the same square-jawed long-haired sword 'n' sorcery guy three times in each panel, changing only their hair color. "Drawing muscled-up dudes will forever and always be fun," he writes of the hulking Genghis-like warlord Khal Drogo in the supplemental materials; "If you hate it, you are in the wrong business." Sad to say, he's probably right, as far as the business goes, but if you're drawing this particular comic, I can't wait to draw the shirtless barbarian who's built like the Incredible Hulk is not the right attitude.

Those backup materials are depressingly revealing, as a matter of fact. Patterson says of Tyrion Lannister, the brilliant little person who's made an Emmy winner out of Peter Dinklage but who's supposed to be far uglier in the book than the handsome actor is on screen, "He isn't handsome so mistakes almost never happen." What a strange implication: You can sleepwalk through drawing the uggos, but the ubermenschen you've gotta take your time with? Again, not the right attitude for this thing. And even if it were, then who knows why all of Patterson's ostensibly handsome men look like their noses have been broken in two places. Or why his women all have feline head shapes, bee-stung porn-star lips, and preposterous tiny-waisted perky-breasted long-legged physiques customary from artists who draw fill-in issues of spin-offs of series begun by J. Scott Campbell or Michael Turner around the time Marvel went bankrupt.

Patterson's children are perhaps the biggest deal-breakers in a story so driven by its youngest characters, in that they're just drawn like miniature adults. The chubby, kindly prince Tommen looks like someone tossed Sidney Greenstreet a blond wig and a shrinking ray, while his sister Myrcella could get a gig dancing at Scores with a convincing enough fake I.D.; both these characters are supposed to have ages in the single digits. The pivotal character Arya Stark, a tomboy nicknamed Arya Horseface in the books, appears to be Natalie Portman. The supplemental material, again: "Arya, who looked too cute and girly, needed to be more substantially reworked [from Patterson's initial character studies], until she looked more like herself." This above a revised version in which her eye makeup looks like La Liz in Cleopatra. An apples to apples comparison with the platoon of gifted child actors selected for HBO's parallel adaptation does the comic no favors at all.

Nor does the art take advantage of the oft-repeated-by-dullards maxim that comics have an unlimited effects budget. With the exception of a single splash page depicting the gone-to-seed King Robert's entourage's arrival at the Northern stronghold of Winterfell, nothing conveys the sense of immense scale in which the book revels. In those gods-damned supplemental materials, we're told repeatedly how vexed Patterson was by having to draw a crowded, sprawling feast in one scene; it's certainly not a mistake he makes twice. And yet the pages still feel crowded and claustrophobic due to Patterson's noisy, uncommunicative line, and the oversaturated digital coloring of Ivan Nunes. The storytelling is clunky as well: Images that deserve focus and space are either given predictable splash pages or all but ignored, with virtually no in-between.

Nor does the book convey the otherworldliness of its few supernatural trappings in this early stage of the story. A key prophetic dream sequence involving young Bran stark was a striking facet of the novel that was dropped from the TV show; all we see of it here are the clairvoyant elements -- "oh look, there's my dad and sisters," that sort of thing -- with the cryptic and horrific elements of the vision elided. Those elements are the subject of feverish fannish speculation on message boards across the internet and would serve as natural catnip were they shown here; perhaps that's precisely why they weren't, but the decision's still a disappointing one. In cases where Patterson does get the chance to show off his supernatural chops, most notably the mysterious ice-demons called the Others in the books and the White Walkers on the show, the result is oddly prosaic and disappointing despite what we're told was close consultation with Martin on getting their look exactly right. They end up looking like they could be a Jack Frost character in an undistinguished fairy-tales-for-grownups series from Vertigo.

I've been hard on Patterson, but ultimately that's a bit like blaming a linebacker for falling on his ass during pairs figure skating. Patterson's just the wrong man for the job. Groell, writer Daniel Abraham, original publisher Nick Barucci from licensed-comics-with-Alex-Ross-variant-covers widget factory Dynamite, and Martin himself are the ones who hired him. Abraham's a successful genre author in his own right for whom Martin has served as a mentor; Groell has worked with Martin since the mid-'90s (full disclosure: I've worked with her myself in annotating A Game of Thrones for the social-reading iPad app Subtext; she's a swell person and an insightful interpreter of this material who I'd imagine, given Martin's legendarily recalcitrant muse when producing this series' remaining volumes is concerned, had bigger fish to fry); Martin is Martin. (Martin moreover got his start as a writer in the '60s superhero-comic fan press, and got as far as a job interview with Roy Thomas at Marvel before leaving the funnybook career path for books and TV.) It was ultimately on them to suss out what's special about A Song of Ice and Fire, and to familiarize themselves with the range of expression available in the medium of comics well enough to select an artist who could translate whatever of that specialness could be translated into sequential-art form, replacing what couldn't with comics' own strengths.

It is, I'm sure, unreasonable of me to expect them to hit up Amazon for Powr Mastrs in between adding the Study Group RSS feed to their Google Readers. But the kinds of alt-fantasy with which comics are currently full to bursting are the most analogous experience I've had to the sophisticated, cynical, strange world of Martin's novels -- a world, I should add, in which I have been increasingly immersed on both an amateur and professional level for the past year of my life. Put more bluntly (and accurately): I fucking love A Game of Thrones, and it's a real disappointment that I recognize much more of it in comics that have nothing to do with it than I do in the one bearing its name and its author's imprimatur.