In an age when the direct market has caused companies like Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly to almost completely curtail their publishing of traditional comic books, it's heartening to see so many smaller publishers and micropresses fully embracing the concept. For a young cartoonist, having the opportunity to publish short stories without the pressure of having to conceptualize and pitch a longer "graphic novel" is an invaluable experience. What follows is a survey of ten comics of various shapes and sizes from small press publishers like Blank Slate, micropresses like Retrofit, Uncivilized Books, and Colosse, and self-publishers.

Let's begin with two artists strongly influenced by the underground and '80s "alternative" era of comics, Noah Van Sciver and Joseph Remnant. The two mine some very similar territory: desperate losers, urban decay, the fruitless search for meaning and connection, maintaining hope in the worst of situations, and above all else, an abiding sympathy for their characters. In terms of visual style, I like to refer to the two artists as the Flopsweat Twins, because so many of their characters have huge beads of sweat pouring from their foreheads. Van Sciver works with a local Denver comic shop to produce his one-man anthology Blammo!, but his latest short comic, 1999, was published by Box Brown's Retrofit Comics, a micropress funded by Kickstarter.

Let's begin with two artists strongly influenced by the underground and '80s "alternative" era of comics, Noah Van Sciver and Joseph Remnant. The two mine some very similar territory: desperate losers, urban decay, the fruitless search for meaning and connection, maintaining hope in the worst of situations, and above all else, an abiding sympathy for their characters. In terms of visual style, I like to refer to the two artists as the Flopsweat Twins, because so many of their characters have huge beads of sweat pouring from their foreheads. Van Sciver works with a local Denver comic shop to produce his one-man anthology Blammo!, but his latest short comic, 1999, was published by Box Brown's Retrofit Comics, a micropress funded by Kickstarter.

1999 ($5, 32 pages) is my favorite of Van Sciver's comics to date. It's the most clever and complex of his comics, filled with a grim sense of doom and ambiguity that's tied to the Y2K panic. His lead character, Mark, is a college dropout who works at a sandwich shop and falls in love with Nora, a fellow shift worker who claims to have an open marriage right before they engage in daily sex on the job. Things naturally go awry. The ending of the comic, beautifully set up with a clever bit of foreshadowing, turns the drama entirely on its head after pulling the reader along through sequences that seem to make no sense, all against the backdrop of a doomsday event that never happened. That Mark will have to keep on living the same miserable life isn't explicitly stated, but it seems the obvious outcome. Van Sciver's line and layout skills have become refined without losing any of the raw, nervous energy that's always been a key element in his comics. He varies his layouts from page to page, slowly adding more panels per page as the comic proceeds and things get more suffocating for Mark. Zip-a-tone style effects are added during both sex scenes and larger images of emotional turmoil, equating the two as a kind of vertigo. He's great at drawing plain-to-ugly characters wearing drab clothing who slouch a lot. This is a funny comic about sad people, which is starting to become a specialty of Van Sciver's.

If Van Sciver's drawings border are grotesque and expressive, then Remnant's characters in contrast are cartoony and crisp. The Crumb influence is obvious, with the slumped-over body language, the dense hatching and cross-hatching used for frequently clever effect (like an overbearing boss always depicted in shadow with heavy hatching), and the parade of desperate characters. Unlike Crumb, Remnant is less interested in working out his id than in telling stories about protagonists who are hard to like but nonetheless evince sympathy. The first story in Blindspot #2 ($5, 32 pages), "Delusions of Grandeur", is about a narcissistic egomaniac whose music draws little more than yawns. The square glasses and unkempt hair paint a portrait of a particular kind of self-serious hipster, who is about to chuck away his career when he gets a single e-mail of praise from someone who was given his album because it couldn't be sold to a used CD store. This is a great example of how Remnant gets away from the direct autobiographical complaining of the first issue and changes things up just enough to make his experiences easy to relate to. The artists and creative types that take themselves most seriously are frequently those who are struggling the most, and Remnant nails this tendency in this story about an otherwise abhorrent character.

If Van Sciver's drawings border are grotesque and expressive, then Remnant's characters in contrast are cartoony and crisp. The Crumb influence is obvious, with the slumped-over body language, the dense hatching and cross-hatching used for frequently clever effect (like an overbearing boss always depicted in shadow with heavy hatching), and the parade of desperate characters. Unlike Crumb, Remnant is less interested in working out his id than in telling stories about protagonists who are hard to like but nonetheless evince sympathy. The first story in Blindspot #2 ($5, 32 pages), "Delusions of Grandeur", is about a narcissistic egomaniac whose music draws little more than yawns. The square glasses and unkempt hair paint a portrait of a particular kind of self-serious hipster, who is about to chuck away his career when he gets a single e-mail of praise from someone who was given his album because it couldn't be sold to a used CD store. This is a great example of how Remnant gets away from the direct autobiographical complaining of the first issue and changes things up just enough to make his experiences easy to relate to. The artists and creative types that take themselves most seriously are frequently those who are struggling the most, and Remnant nails this tendency in this story about an otherwise abhorrent character.

"It Changed Everything" pops one character's hubris in the form of a fart joke, as a sure-thing date goes awry. It's an OK gag as far as it goes, but I'm glad Remnant confined it to just two pages.

The showstopper of the issue is "Lip Candy", featuring an ad writer named Bill Wilkinson who is pretty much the opposite of Don Draper: covered in flop sweat, portly, disheveled, paranoid, and hostile. Trying to get one up on his admittedly smarmy and younger coworker, he goes behind that coworker's back to get an audience with his boss to present an ad campaign for a lip balm that he sees as a sure thing. Instead, the whole plan backfires spectacularly and in the most humiliating way possible. Bill has a lot of bad things happen to him, but they're entirely his fault and no one lets him off the hook--not even his bartender, who hilariously dresses him down instead of offering him unconditional support. The end of the story, after Bill finds he can't even get revenge on his coworker without screwing up, does offer a slight ray of hope, but it's hard-earned. The schlubby Bill is a triumph of character design, looking old-fashioned yet timeless in his ill-fitting suit and five o'clock shadow. Throw in an old-fashioned letters page, a tribute strip to Harvey Pekar (for whom Remnant illustrated the fine swan song Harvey Pekar's Cleveland), and an autobio bit of slice-of-life about a security guard that is very much in Pekar's style and voice, and you have an enormously satisfying comic by a talented cartoonist who has just started to realize his considerable potential.

Going back to Box Brown, he's made quite an impact on the comics scene in the past year with a number of well-liked and award-winning comics as well as his ambitious Retrofit project. His own entry in this monthly series of comics is Chubby Chasers ($4, 24 pages) , a minicomics-sized comic that partakes in the Dave Cooper aesthetic by way of Gilbert Hernandez. The cover, an overlapping series of circles with various shades of pink, is in itself a clever visual gag that still manages to capture that particular aesthetic of big, beautiful women. The main story is about a schlubby drug store clerk who meets a big woman at a club and winds up having the best sexual experience of his life. Despite this fact, he's still embarrassed to be with a bigger woman and doesn't want to tell his workmates, totally oblivious to the fact that he's a loser in a dead-end job. When he gets fired by his boss (herself a bigger woman), Brown cleverly has the character deflect blame to all fat women in general, even as his previous date is going out and having a good time yet again. The Gilbert Hernandez influence is even more pronounced in the back-up story, which is four days in the life of the painter Peter Paul Rubens. The painter was well known for painting bigger women, and Brown sets up the influences for his desire—how he thought about painting, how he dealt with typical models, and how he moved on to a different subject—as single-page gags. The latter story is more compelling overall than the feature, which feels a bit predictable.

Going back to Box Brown, he's made quite an impact on the comics scene in the past year with a number of well-liked and award-winning comics as well as his ambitious Retrofit project. His own entry in this monthly series of comics is Chubby Chasers ($4, 24 pages) , a minicomics-sized comic that partakes in the Dave Cooper aesthetic by way of Gilbert Hernandez. The cover, an overlapping series of circles with various shades of pink, is in itself a clever visual gag that still manages to capture that particular aesthetic of big, beautiful women. The main story is about a schlubby drug store clerk who meets a big woman at a club and winds up having the best sexual experience of his life. Despite this fact, he's still embarrassed to be with a bigger woman and doesn't want to tell his workmates, totally oblivious to the fact that he's a loser in a dead-end job. When he gets fired by his boss (herself a bigger woman), Brown cleverly has the character deflect blame to all fat women in general, even as his previous date is going out and having a good time yet again. The Gilbert Hernandez influence is even more pronounced in the back-up story, which is four days in the life of the painter Peter Paul Rubens. The painter was well known for painting bigger women, and Brown sets up the influences for his desire—how he thought about painting, how he dealt with typical models, and how he moved on to a different subject—as single-page gags. The latter story is more compelling overall than the feature, which feels a bit predictable.

On the other hand, Brown's book from Blank Slate, The Survivalist ($8, 44 pages), is an impressive achievement because it turns a right-wing conspiracy theory wingnut into a compelling and sympathetic leading man. Half the book follows an alt-comics lump toiling away in loneliness, typical except for the fact that he's a conspiracy theorist. As the story begins, he awkwardly interacts with people at his job (lecturing two women on the dangers of vaccine-induced autism) as a meteor heads toward earth. The Rush Limbaugh-type radio personality he admires insists that the astronomical threat is liberal scare-mongering ... until the meteor actually hits. Our protagonist, Noah, survives because he has begun sleeping in the bomb shelter that his father built in the 1950s. After the crash, he meets another survivor and forms a tenuous friendship with her, even as he works on drawing comics (his true love). Brown slowly unravels Noah's story in light of his friendship with Fatima, peeling away the layers of pain and despair that he wrapped up in his conspiracy theories. Fatima's insistence that everyone has a story to tell, "if we are truly open and honest about it. Even yours," serves as motivation for Noah, and allows Brown to prove the same point. The end of the story is genuinely moving as Noah finds a way of coming to terms with his old grief as he deals with new grief. Brown's slightly grotesque and cartoony style (somewhere between Beto and Chris Ware) looks great in the Blank Slate "Chalk Marks" series format, with its large-periodical size, dust cover replete with diagrams, and excellent paper stock.

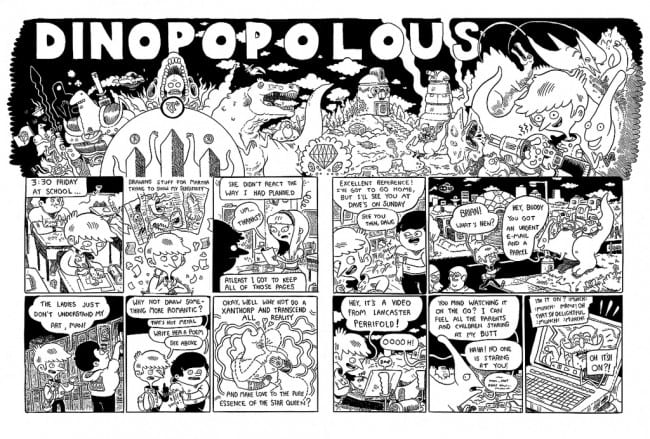

The Chalk Marks line is specifically designed for young artists publishing new works. This one-and-done format is perfect for those cartoonists who aren't yet ready to produce the graphic novels that the market tends to value most, by giving the artists the backing, expertise, and production values of a publisher that's willing to push short-form comics as worthwhile in and of themselves. Small press publishers can get away with this because so much of their business comes from the convention circuit, and I predict that the Chalk Marks books will fly off their table when Blank Slate comes to SPX for the first time this year. A couple of recent examples include the all-ages book Dinopopulous ($8, 44 pages), by Nick Edwards; and A Long Day of Mr. James-Teacher ($8, 44 pages), by Harvey James.

Edwards' book is about an imaginative young boy who has real-world concerns about trying to get a girl to like him, but is still more interested in the adventures he goes on with his talking dinosaur. This comic is a mash-up of Indiana Jones, role-playing games, video games, puzzles, and activity pages--all things that Edwards himself clearly delights in. This is obviously an instance of a comic drawn by an artist to entertain himself, and it's one of the more complex and rich all-ages comics I've seen. The story itself is simple, but Edwards alternates a simple, cartoony style with highly-detailed eye-pops, mazes, and surreal imagery to create a story that's slight as a story but entertaining as a journey through an environment. Edwards reminds me a little of Jon Chad and his comics for kids, Leo Geo in particular. He's not yet the storyteller that Chad is, but there's still a sense of excitement on every page.

If Edwards' comic is noisy, then Harvey James' comic is quiet. It's an autobio story about a single day spent as a teacher in South Korea, depicting the artist's passion and insecurity as he deals with a tough mentor and students who (he believes) no longer respect him. The insights gained here are small ones, with no special resolution to the conflict in the course of the story. It's the story of a single day--no more, no less--with typical highs and lows. James doesn't go out of his way to put himself down; rather, he's honest about all of his emotions, be they positive or negative. What distinguishes this comic is James' skill as a cartoonist. I can't be sure of his influences, but it looks like there's a bit of Jeff Smith in there in how he draws exaggerated character behavior, slows time down to create a gag, and balances cartoony and naturalistic drawing. A sequence at the end of the book, in which he draws his characters in the rain, is simply beautiful cartooning as the forms of his characters melt into the rain and become just patterns of lines. As with all of the books featured in this series, there's a tremendous sense of confidence on display on these pages; the cartoonists seem to have tried as hard as possible to merit the benefits of the format and opportunity they've been given.

One of the most intriguing art objects I've seen is Sophie Yanow's In Situ ($12, 40 pages), a comic published by Montreal's Colosse as the first in its "Exports" series. It looks less like a comic than it does an interesting, slender paperback that one might find at a store like St. Mark's Bookshop. This is an innovative, clever diary strip book that is strongly influenced by the poetic abstraction of John Porcellino. (Yanow is even seen wearing a King-Cat t-shirt in the course of the book.) The story finds Yanow being offered a grant to draw comics full time in Montreal, while she finds herself betwixt and between her hometown of Oakland. Yanow tries all sorts of formal tricks and visual styles to go along with her frequently opaque and personal storytelling references. It's less important that the reader know what's going on on a day-to-day basis than it is understanding what Yanow is struggling with on an emotional, political, creative, and philosophical basis. Yanow varies her line, going from a slightly blotchy Gabrielle Bell style heavy on spotted blacks to clear-line naturalism to hasty scribbles to cubist-inspired drawings of motion to single drawings split across six panels.

One of the most intriguing art objects I've seen is Sophie Yanow's In Situ ($12, 40 pages), a comic published by Montreal's Colosse as the first in its "Exports" series. It looks less like a comic than it does an interesting, slender paperback that one might find at a store like St. Mark's Bookshop. This is an innovative, clever diary strip book that is strongly influenced by the poetic abstraction of John Porcellino. (Yanow is even seen wearing a King-Cat t-shirt in the course of the book.) The story finds Yanow being offered a grant to draw comics full time in Montreal, while she finds herself betwixt and between her hometown of Oakland. Yanow tries all sorts of formal tricks and visual styles to go along with her frequently opaque and personal storytelling references. It's less important that the reader know what's going on on a day-to-day basis than it is understanding what Yanow is struggling with on an emotional, political, creative, and philosophical basis. Yanow varies her line, going from a slightly blotchy Gabrielle Bell style heavy on spotted blacks to clear-line naturalism to hasty scribbles to cubist-inspired drawings of motion to single drawings split across six panels.

This change of style lends a visual representation to Yanow's feelings of everything being possible in a new, exciting creative environment but feeling equally drawn to her home and the loves she's left behind. No romance is more important than the city itself, as she's away from Oakland during the contentious Occupy Oakland that inspired vicious police crackdowns. The last page of the book is a sort of recapitulation of the work as a whole, as she runs through different styles on a panel-to-panel basis in a nearly-unbroken 2x3 panel grid. In the last four panels, she writes, "Decided/ The only things worth doing:/ Dancing, drawing/ Smashin' the state." The last image is the cover image: a contorted, dancing figure with an obscured face, a dancing anarchist, drawing her own revolution. This is a beautiful first major work by an artist who is quite clearly concerned about how she affects the world, in terms of both art and politics.

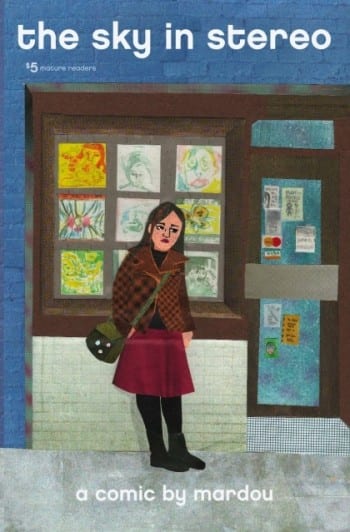

Another personal work that's about the same size and shape of In Situ is Mardou's The Sky In Stereo ($5, 52 pages). Mardou has a knack for creating characters who feel achingly real without actually dipping into the autobio well. The British cartoonist here writes about Iris, a 17-year-old girl in Manchester who starts the comic by saying, "I'm so bad at this." She's referring to being stoned, but it's also clearly a representation of how she feels about her entire drab life. What follows is an attempt to change things by way of a flirtation with a cool guy at her fast-food job. Mardou's eye and ear for detail and dialogue is uncanny, perfectly capturing the simultaneous sense of ennui and excitement that something amazing might happen. She has a simple and sometimes even shabby line that nonetheless adeptly captures slight modulations in emotion; the looseness of her line allows her to focus on expressiveness and gesture in her characters.

Another personal work that's about the same size and shape of In Situ is Mardou's The Sky In Stereo ($5, 52 pages). Mardou has a knack for creating characters who feel achingly real without actually dipping into the autobio well. The British cartoonist here writes about Iris, a 17-year-old girl in Manchester who starts the comic by saying, "I'm so bad at this." She's referring to being stoned, but it's also clearly a representation of how she feels about her entire drab life. What follows is an attempt to change things by way of a flirtation with a cool guy at her fast-food job. Mardou's eye and ear for detail and dialogue is uncanny, perfectly capturing the simultaneous sense of ennui and excitement that something amazing might happen. She has a simple and sometimes even shabby line that nonetheless adeptly captures slight modulations in emotion; the looseness of her line allows her to focus on expressiveness and gesture in her characters.

The comic and its protagonist are mean and petty at times in the way that downtrodden characters can get, but there's also a sense of desperate beauty to be found at the end of this first issue. Drugs are a running through-line in the comic: a means of escape, a means of fitting in (and "doing it wrong"), a means of adding color and laughing. When one of the characters tries heroin and likes it, it leads to an interesting set of emotional twists for the protagonist, who partly wants to say she'll go along with him and is partly frightened until the issue's climax. Mardou crams most of her pages into nine-panel grids, making the reader feel cramped and trapped along with the characters. The result is both uncomfortable and strangely intimate, as we're forced to identify and sympathize with the characters even when they make questionable choices.

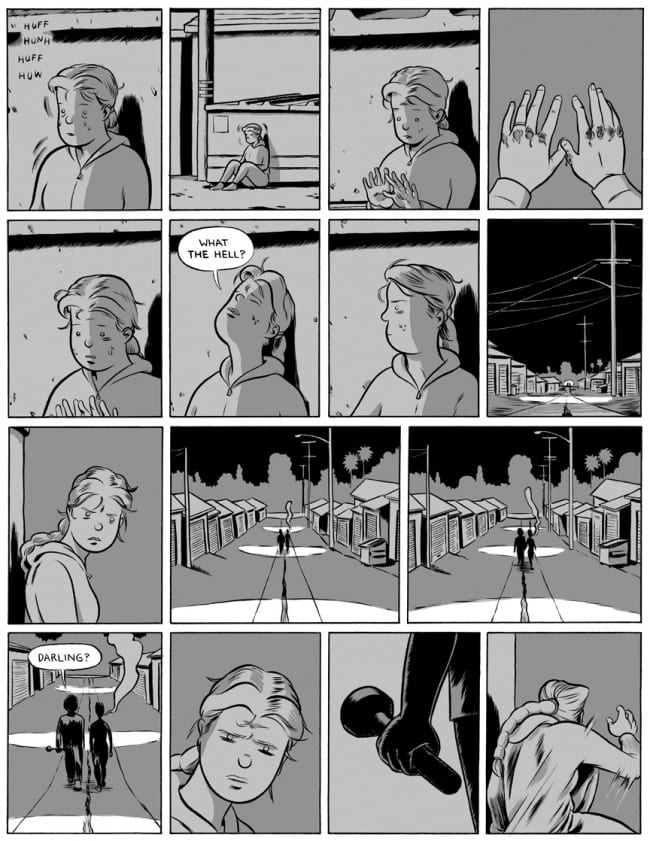

One of my favorite small presses is Revival House, and they've upped the ante in terms of production with the first issue of Malachi Ward's comic Ritual #1 ($6, 30 pages). It's magazine-sized, like the Chalk Marks books, though without the dust covers. Half of the comic is a slice-of-life comic following the slow disintegration of a relationship through the eyes of a slightly portly blonde woman who is haunted by a dream she has about beetles burrowing under her boyfriend's skin while she silently watches. The story concludes with the power going out in their building, prompting the couple to hang out with their female next-door neighbor.

One of my favorite small presses is Revival House, and they've upped the ante in terms of production with the first issue of Malachi Ward's comic Ritual #1 ($6, 30 pages). It's magazine-sized, like the Chalk Marks books, though without the dust covers. Half of the comic is a slice-of-life comic following the slow disintegration of a relationship through the eyes of a slightly portly blonde woman who is haunted by a dream she has about beetles burrowing under her boyfriend's skin while she silently watches. The story concludes with the power going out in their building, prompting the couple to hang out with their female next-door neighbor.

The comic then segues into a creepy, distancing Invasion of the Body Snatchers pastiche that nonetheless is emotionally connected to the first half of the comic when the protagonist sees her boyfriend and her next-door neighbor making out in front of her, after her boyfriend makes a cutting comment about her piano playing. Everything seems real, despite the strange pustules on each of their faces, eerily mimicking the beetles seen earlier in the issue. Did the strange flash of light they all saw herald their infestation? The issue ends with a tense chase scene and an ending that isn't exactly a happy one. Ward really hits on something interesting in this comic whose style has the distancing cartoony quality of Chris Ware along with a more lumpy sense of character design. By creating a believable domestic scene whose tension and quiet desperation is all too familiar to alt-comics fans, Ward is able to cleverly subvert the expectations of the story while still heightening those feelings. Ward is an exciting young talent who is traveling the fusion path à la Michael DeForge, but in a completely different way.

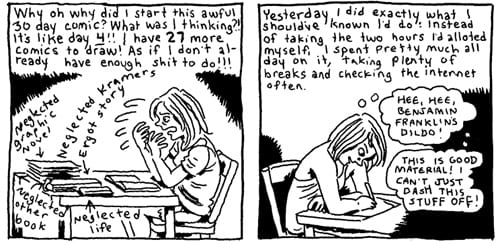

Finally, Tom K's Uncivilized Books just published the newest comic by Gabrielle Bell, one originally released on her website in July of 2011. July Diary ($6, 52 pages) is the result of Bell drawing and publishing a strip a day during that period, forcing her to show her work to an audience, warts and all. Bell and Vanessa Davis are my favorite comics diarists, though their approach and attitude couldn't be more different. The quintessential Bell quote from her autobio comics appears here: "I am so lonely...and yet I can't stand the company of anyone." For a comic that wallows in this contradiction, Bell proves that she's a top-notch humorist and even absurdist on page after page. Her comics persona is that of a barely competent human being (afraid of being called "traitor" by street people) who stumbles through life, getting into all sorts of awkward and amusing situations. What's interesting is that for the purposes of doing this strip every day, she found herself manipulating her life so as to produce funny anecdotes, going so far as to follow some strangers into a bar in order to hear their stories.

Finally, Tom K's Uncivilized Books just published the newest comic by Gabrielle Bell, one originally released on her website in July of 2011. July Diary ($6, 52 pages) is the result of Bell drawing and publishing a strip a day during that period, forcing her to show her work to an audience, warts and all. Bell and Vanessa Davis are my favorite comics diarists, though their approach and attitude couldn't be more different. The quintessential Bell quote from her autobio comics appears here: "I am so lonely...and yet I can't stand the company of anyone." For a comic that wallows in this contradiction, Bell proves that she's a top-notch humorist and even absurdist on page after page. Her comics persona is that of a barely competent human being (afraid of being called "traitor" by street people) who stumbles through life, getting into all sorts of awkward and amusing situations. What's interesting is that for the purposes of doing this strip every day, she found herself manipulating her life so as to produce funny anecdotes, going so far as to follow some strangers into a bar in order to hear their stories.

Even if Sammy Harkham declares that Bell hangs out "with a bunch of lunatics," they are sterling comedic catalysts for her comics. Whether she's depicting her misadventures with Karen Sneider on a temp computer installation job (which feature an excellent fart joke), her observations of a huge statue of Echo's head in a park and how the different kinds of crowds affect her impact (ultimately imagining the rest of Echo waking up and going on a rampage), or the insults hurled by her ex-boyfriend Michel, Bell's mix of bemusement, affection and awkwardness make for reliable laughs. This is what really distinguishes Bell's diary comics from others: while she's trying to share some of her feelings of disconnection, she's always doing it in the form of a humorous situation of some kind. Bell's ability to make funny drawings is underrated, and she increasingly relies on it in this comic as she starts to run out of ideas, as in the drawings of various disgusting bodily functions that she overhears someone talking about. Even Bell's frustration at running out of inspiration is funny, as she starts to make up imaginary vacations where she eats volcanoes. Funnier still is that the big party for one of her books that she's nervous about is something she doesn't want to talk about, even if she apparently did all sorts of crazy things. Even in her own comics, Bell is uncomfortable with being the star, just one of the many contradictions that make her work so interesting.