This intro was written for The Comic Journal Library Vol. 6: The Writers (2006).

This intro was written for The Comic Journal Library Vol. 6: The Writers (2006).

Dennis “Denny” O’Neil was one of the most highly regarded comic book writers of his era. His best-remembered work is his run on Green Lantern/Green Arrow with the artist Neal Adams, a full-on embrace of various societal issues that felt to many fans like the first step towards an adult superhero literature as far beyond the bombastic soap opera of the early 1960s as those comics had been an advance on the one-dimensional pulp of the 1940s and 1950s. That series was also one of the first times a mainstream comic company had injected new life in a second-tier project by providing a shift in narrative tone, an editorial technique that would come to be used by both Marvel and DC in the decades to come for projects that felt like they could benefit from such a boost.

O’Neil also wrote well-received runs on Batman, The Question, and a revival of the pulp character The Shadow. His influence was so dominant that at one point O’Neil’s comics practically defined how you wrote books for an older and potentially more sophisticated audience. His treatment of Batman as an editor and writer effectively put a final end to his dalliance with camp, and echoes of this approach have been seen in every version since the mid-1970s. He has since the time of this interview conducted in 1978 and 1980 and released in full form in TCJ #66 (September 1981), become a more significant influence as an editor. His work as a writer has come on occasional projects like the Batman Begins video game.

O’Neil was one of the more formidable thinkers among his peers and projects an impressive presence throughout the following interview. O’Neil talks about his work but also speaks to general issues about making art and the value of what he does for a living.

GARY GROTH: You’ve often referred to yourself as a “commercial writer”…

DENNY O’NEIL: Yeah, in that I never started from the standpoint that I have anything to say to the world. Harlan Ellison said he never writes for anyone but himself. You, I assume, write for an audience. I never write for myself. I mean, I write for me — if I do a comic, I say, “All right, I’m Denny, and I’m out there and I feel like reading a comic book. What would amuse me if I felt like reading a comic book?” That’s as close to writing for myself as I get.

Sometimes I’ve done stories with specific people in mind, like, “I want so-and-so to read this. This is a story for X.” Once, I wrote a story for a specific individual and I wanted her to read it and say, “Hey, I’m not mad at you, this is what really happened.” I can express myself better in fiction than I can verbally. But, those things are very rare and they’re also terrible self-indulgences on my part. Professionally, I can’t ever justify writing a short story because I don’t make any money on it. But I don’t, on the other hand, almost ever, start off because there’s something I want to say or even something I want to express.

I think if Harlan has never written a story for anyone but himself, then he’s been very lucky that he’s found such a large number of people who are simpatico to what he does and that’s quite possibly what goes down. But, it’s not where I started from at all.

When I left college, I never thought I would create another piece of fiction in my life. I was sure that that was all behind me. I didn’t have any desire to write fiction… I mean, I had a niggling desire to do it, but I didn’t anticipate making it my life’s work. I didn’t know what my life’s work was going to be, so I went into the Navy to kill time, and I came out and taught for a while. I didn’t like that very much, I didn’t like the apparatus of the school system. I said, “What else can I do? I have to eat. All right, I’ve done journalism, I can be a journalist, I know how to write a news story.” So I answered an ad in the back of Editor & Publisher: “General Reporter Wanted. Small Missouri town.” I got the job and found that I could indeed function as a reporter. Then I came to New York and found I could function as a comic-book writer, that I had whatever it takes to be able to do that, at least on some level.

You’ve said in the past that when you entered comics, over a decade ago, you had the intention of working in comics only about six months to make some money and then splitting. How come you’ve stayed about 12 years or so?

Because I had a child sooner than I could have anticipated, and we thought it would be bad, with a baby, to pull up stakes and schlep back to the Midwest. Then we began getting involved in the neighborhood; I began to find an aptitude for doing this stuff that I hadn’t had any reason to believe existed. I began to enjoy doing it. I began to pick up other things that were interesting to do — magazine pieces. The first thing I knew, there didn’t seem to be anything to go back to in the Midwest — four years had passed and the job that I had come from undoubtedly wasn’t there anymore. It was more sensible to stay and keep doing comics than to try and go back to journalism. Also, I began to really dig it about that time. I began to get reorganized; my ego got some stroking — that didn’t hurt — and I found that I could be really happy writing a comic-book script that I thought was pretty good.

Do you enjoy writing comics as much now as you did in 1967?

A tricky question. I enjoy exercising the craftsmanship that I have gained. Ah, to use a word that I don’t like to use, creativity — the exercise of that I still enjoy. I don’t get as fantastically high as I used to do when I do a good job, but that has as much to do with the field as with me, though…

How so? The field has changed since you’ve come in and after?

I think it’s a duller place to work than it was seven or eight years ago. Seven or eight years ago there was a feeling that we were taking an art form, a minor art form, but an art form, and advancing it. And that we were doing the best stuff that had been done. I mean, not only I had that feeling, but a lot of people. And we were opening whole new vistas, and we were coming up with new ideas and new places to go and new things to try. Now I sense that it has gotten to be very sedate, plain, ordinary… I would expect that it is a lot like working in an ad agency now, which doesn’t mean that there is no satisfaction or no creative kicks involved, it’s just not a feeling of working in new areas, of opening possibilities, of becoming, you know, in the existential sense. The people who are new in the field don’t seem to be having as much fun with it as Steve Skeates and Neal and I did back when we were just starting. It seems to be more of a job to them. It was kind of an adventure for us for a while. There was a tremendous feeling of camaraderie, of feeding off each other, getting ideas constantly. It was a terrific place to be working in 1971.

In ’71 you were more or less a real hotshot writer because of the Green Lantern/Green Arrow books.

Yeah.

And now, I don’t think you are quite regarded as the same. Would you agree with that assessment?

Oh, absolutely, sure.

How does it feel to come down from that peak?

Well, what happened was that I had about two or three really bad years — personally and professionally. That shouldn’t be a secret to anybody. But because of what was happening, I wasn’t aware of coming down when it was happening. There has been, I think, a recovery from that, and I’m not at all unhappy with the way things are now. I’m not getting the publicity and the tremendous fame, but I couldn’t reasonably expect to continue at that peak. That was, after all, a time and a place kind of thing. I was doing something that was considered daring at the time. If I did the same thing today it would be considered commonplace.

Do you really think so, considering how dull things are now?

Well, they would say, “He’s done it before, it’s been done.” And other people have done it. Other people like Gerber have maybe taken it a step further than I did.

How would you rank your GL/GA books?

All I can say about that is that people still talk about them eight years later, and how many comic books is that true of? I haven’t reread them at all. I would suspect that they stand up as comic-book stories. I think there was more to them than just the relevance. At the time, I was very conscious that my first duty was to turn out a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and preferably some suspense and some characterization and some imaginative use of the superhero format. That was and still seems to me to be my primary job when I sit down to do a comic book, and I don’t think I neglected it back then.

Do you think that was a high point in your comics career, in terms of actual achievement?

No, I think I’ve done other stories that were technically every bit as good as any of those. In fact, some of the Batman stories were technically quite a bit better. It was a high point in terms of the amount of attention I was getting, sure, but in terms of professional achievement, no.

You said comics were a minor art form. Can you define an art form?

No, I can’t. Art is what artists do. Anything that is an expression of something is probably an art form. That goes for racecar driving as practiced by people like Stirling Moss, and any form of music or storytelling or picture-making with paintbrushes or cameras or whatever. That’s a question that’s been argued since the 15th century at least and I’m not about to attempt to wrap it up in two neat sentences here now.

What would you consider a major art form?

Cinema, music, the novel, drama — though comics as practiced by Will Eisner come very close. And I don’t mean to denigrate comics because I consider the short story a minor art form and it’s certainly respectable and valuable… It’s just that not as much is possible with a short story as there is with War and Peace or Hamlet. It largely has to do with the matter of inherent limitations within the form.

Do you make the distinction between high culture and popular culture?

Yeah, I think it’s necessary to make that distinction. But I think it’s a distinction that’s disappearing, and the sooner the better.

Really?

Yeah.

Why?

Well, because it’s a distinction that’s largely fostered by people who teach in universities who have a vested interest in terms of their jobs in making the division because a popular culture is obviously something that’s accessible to everyone and high culture, haute culture, isn’t, therefore it needs to be taught, therefore people have to teach it, therefore if you want to get your tenure as a professor… It is self-serving of those people to make the distinction.

But, I think it’s largely a matter of inaccessibility in terms of language. I mean, Dostoevsky’s novels have to be taught because we are not very familiar with the Russian customs and the popular thought when Dostoevsky was writing, therefore they are not entirely accessible to most of us on first reading, therefore someone has to explain things about them. The same will be true of popular movies in 50 years probably. They will tell you that there is High Culture and it deals with loftiness and so on. I’m not an expert on this stuff, but as far as I can see, historically that is not really true. After all, Dostoevsky’s novels were, most of them, published in the popular magazines of the day. The Idiot was a serial in a magazine. So, obviously, he was shooting for a big audience. The classic example is Shakespeare who was shooting for the guys who were getting drunk in the pit down there. The passage of time makes a thing a) respectable, b) inaccessible, and c) susceptible to being taught.

How do you see comic books now? Working in the field for 13 years, your views must have changed. What do you try to do in a comic book these days?

Entertain. End of discussion. That’s it. I try to be amusing on paper.

There are ways of being amusing. Like a fight is in one sense amusing. And in an equally valid way a revelation of character, which can be very quiet and subtle, is amusing. So, I try and work all the ways there are to work. Even when I was writing Green Lantern, I wasn’t trying to tell anybody how to run the world. The basic mistake that always gets made about those stories is that they were proselytizing. They were not! They were saying, “These problems exist. Look at them.” That’s as heavy as I ever wanted to get. If I had solutions to the problems, I wouldn’t use a comic book as a vehicle to express them. And anybody who reads that so-called “relevant” stuff that I wrote for Green Lantern or before that for Charlton or since occasionally for whatever I happened to be working in will see that I never proposed a solution. I have just said, “Hey, let’s not be complacent, because it’s treacherous out there.” And there are problems that we have to deal with.

Have you grown to hate the word “relevance?”

Yeah, it’s not my favorite word anymore.

Seven years ago you said, “Beginning writers in comic books should not try to be creative, they should be commercial.”

Yeah, I probably said that.

Are the two anathema to each other?

I don’t know. I guess what I meant was that you should learn the craft; you should learn the form before you try to transcend it. I absolutely believe that today. And I can’t think of a single way to cite an exception.

I will give you some haute culture examples if you want. James Joyce’s first book of short stories, The Dubliners, is quite a traditional collection of very well-crafted ordinary stories. That was before he did Ulysses or Finnegans Wake. Picasso’s first pictures were very representational and photographic. I think you always have to learn the craft in anything. And in terms of comic books, being commercial is learning the craft. Do what other people did first until you know how to do it as well as they did and maybe you could figure out new ways to go. It seems to me it’s a bad thing for writers to try to be awfully innovative early on, and I can give you examples of how that’s loused people up, but I won’t because I don’t want to insult anybody. But, people who come in with a kind of “That’s only commercial stuff” attitude, maybe don’t realize how hard it is to be commercial. It’s what James Agee called “the very difficult task of being merely entertaining.”

And how many people bring it off? How many Marx Brothers have there been? They’re only funny, right. No great messages for the world. But nobody’s come close to them at doing their thing. That’s what I meant.

How long did it take you to learn the craft?

I don’t know. I would guess that I wrote 50 stories before I began to be comfortable with what I was doing.

What were some of the tricks of the trade you had to learn?

Learning to express things very economically; learning to move a story and to not let it lag; learning to compose a story so that there’s a small kicker in the last panel, there’s some reason to make you turn the page, a mini-cliffhanger, or question that needs to be answered or something like that. Largely it’s a matter of learning how to pace a story and I don’t know of any way to teach that. Keep it moving; keep it interesting. Work contrast between the high moments and the quiet moments, make them work off one another so that the quiet moments aren’t dull, but create a tension between the more active or violent scenes. It’s a subtle thing and I don’t know of too many people who do it and I don’t know of any way to teach it.

Except by doing it.

Yeah. Any kind of writing that’s largely true of. The rest of it is craftsmanship — learning how to do characterization without going into a long soliloquy about what the guy is, being able to pin a character in maybe three sentences or one characteristic action so the reader knows everything he has to know about him in a very short time.

Several writers or craftsmen in the industry have said that writers versed in other forms of writing — novelists, for instance — could not necessarily write a comic book. Do you think that’s largely true?

Yeah. A couple of novelists I know who have tried haven’t been very good at it.

Do you think that the majority of good writers could write a comic book if they have a firm hold on their craft?

No, I think that they need to understand what I, in a recent speech at the MWA, dubbed the übergrammar — hey, I was not a philosophy minor in college for nothing — it has to do with the fact that the visual and the copy form one linguistic unit, and you have to have a natural sense of how that language, that peculiar language works. In crudest possible terms, if I say, in a caption, “However…” and the visual is Batman socking somebody, it’s analogous to the subject and the predicate of a sentence, one being visual, but they form the same linguistic unit, the same unit of communication even though they’re different things. They work off each other, they complement each other, they create tensions within the panel. You have to have an instinctive grasp of what that’s all about in order to do this. I think the instinctive grasp comes from being exposed to this particular form of storytelling at an early and formative age, at the time when maybe we’re learning English. Most of the good comic-book writers I know were seeing comics when they were 3, 4, 5, 6 years old, at about the time they were learning to speak. And I think they learned the [comics] language along with English. They picked it up subconsciously, and when they went away to college or wherever they went and picked up sophistication, they brought some of that. But, I think those of us who are good at this have at an early age learned it like a second language. And almost none of us, unless we’re Vladimir Nabokov or Joseph Conrad, are fluent in our second language. I’ve reached this conclusion only after talking with dozens of guys and trying to figure out why I can do this and x-novelist, who’s a much better writer than I am, can’t.

So you would say a visual literacy is a sort of a second language?

Yeah. My first exposure to any kind of art was comic books and my second was movies. I didn’t see a novel until I was about 9 years old. I didn’t really know they existed. The good writers I know who don’t seem to do comic books very well were reading novels maybe at six but did not have comics around the house. And sociologically, we all seem to be from the lower middle class.

What is visual literacy and how does one learn it?

By looking at lots of pictures, all kinds of pictures: Paintings in museums, photographs, comic books, television shows, movies. It is an understanding of how images convey story or emotion or idea.

Should visual literacy be taught?

Yeah, I think it should be taught. It’s not news — ever since McLuhan — that we are moving into a more iconic culture, meaning we are more and more visually oriented, and I think it’s as important culturally to be able to understand with your eyes as well as the left side of your brain.

How much of McLuhan do you buy?

I haven’t read him for years and years. I think he had some insights. The last time I thought about McLuhan I thought this: He had some insights into specific things that he tried to stretch to cover everything, which is a common failing among people who have insights. Martin Buber did the same thing. To some extent, so did Plato, so it’s OK.

Where do you think things have gone wrong with comics, economically?

I think that we’re 20 years overdue from realizing that Mom and Pop stores don’t exist in most places anymore, and therefore the main retail outlet for comics has been quietly going out of existence all these years. That’s not my problem, that’s the problem of the guys who went to the Harvard Business School. They’re supposed to know about that. I think that as far as the writers and the artists are concerned, the reason that we are in — and Paul Levitz and a few other people would violently disagree with this — but I think that among so-called creative people we are in the worst economic position. The television writers have a pension plan. Every time you do a TV script, x-number of dollars gets put in that the companies have to match and that’s your retirement. We don’t have anything approaching that. We don’t have very much in the way of medical benefits; what’s considered normal fringe benefits for a guy who works on an assembly line we don’t have. If I go dry and I absolutely can’t write for some reason for a year I’m dead. There’s nothing I can live on unless I have money saved. That’s not true of anybody else in any other field, especially not with a large backlog of material.

But I think that’s just because the guys in 1945 didn’t do what was necessary to do to get those benefits. As [Steve] Gerber has pointed out, guys who have been working in this field have been just so grateful to the companies for giving them the privilege, the opportunity to work out their fantasies on paper, that they have not worried about simple, economic facts, such as cost of living raises, which I now get, but which isn’t usual in the field and hasn’t been at all except for about the last three years. I think that’s one of the benefits of Jenette Kahn. She began to see that we needed those things that every other stratum of society gets as a matter of course and has been taken for granted for 25 years. But, see, in 1945, Superman was selling nearly a million copies a month and that was the time for those guys to demand their rights and they didn’t do it, and I think it’s too late now.

Would you say that the comic-book industry has been run pretty ineptly, financially, for the past 30 years?

Yeah. I don’t know very much about finance or business, but as an interested layman, I’d say that was pretty obviously true. I think there are steps being made to remedy that now. Whether there will be enough and in time, we don’t know.

What are they?

Well, I know that there are different distribution systems being experimented with. There are studies being made. There is talk of going to European format, which makes a lot of sense since comics don’t have to be periodicals. They happen to be periodicals because that’s what they started out being, but there’s no reason why the average Superman story won’t be as good or as bad five years from now as it is now.

Do you have any idea why the business aspects of comics have lagged so far behind the other entertainment industries?

Yeah. Because I think it was a very déclassé business and it didn’t attract bright business minds. If a guy’s smart and he comes out of business school, he’s not going to think about going into comic books. He’s going to think about going into television, or into slick magazines or something like that. We simply haven’t attracted the talent in that department. I don’t know if that’s currently true because I have no idea who’s running the show in that department now. But it has been true, undeniably. Guys who maybe had a rough, crude kind of shrewdness started the business. I don’t have to mention names because anybody who’s familiar with the medium knows what the names are. And that was OK when comics were a hot thing. When they were the lowest common denominator entertainment and they were for a long time, therefore they were a mass medium, therefore for a while all they had to do was get ’em printed and put ’em on a stand and the rest sort of took care of itself. Gradually that became untrue, but they didn’t realize that it wasn’t untrue until they were already in trouble.

I don’t think comics will even be, by any stretch of the imagination, a mass medium in 10 years. I think it will be a specialized medium. I think that you won’t buy them because, hey, this is a simple form of story that’s accessible to anybody and it’s exciting because that’s television now. I think people are already buying comics for the unique satisfactions of the medium, for the manipulation of the language that I was talking about before. In a sense it’s getting to be almost like poetry, it’s something you have to have a taste for. It’s moving in that direction. I think that’s the wave of the future. The comic book will be a genre particular to itself, no longer mass entertainment, but something that, hopefully, 300,000 people in the country will really dig and really like enough to invest money in.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

Currently?

No. The whole gambit.

It’ll sound pretentious. It will. Let’s stick with contemporary people because if I say Shakespeare I’m going to sound like one of those pretentious assholes who are always culturally name-dropping.

I currently like John D. MacDonald as a novelist who does not write novels for English majors, and I think that is a consummation devoutly to be wished. By contrast, John Updike, who does write novels for English majors.

You have no great love for academics, do you?

No. I’m softening about that. I’m coming around to thinking they’re not as worthless as I once thought them to be. I question whether anyone should attempt to teach culture in a college because it seems to me you either respond to a work of art or you don’t and what the artist was doing was trying to make you respond emotionally or intellectually to what he was doing. I don’t know if you can properly assign grades to that. I was an English major in college and I regret that now. I also taught English for a year in the St. Louis public school system. I think you can teach reading, you can teach language. But how do you say a kid gets an F because he did not respond to The Brothers Karamazov? And now comics are being taught in colleges and it freezes my bowels to think some poor kid is going to be sweating over a blue book on a final over some stupid little story that I dashed off in an afternoon to meet a deadline. I want to amuse them, I don’t want people to fret over my work, and if it gets very much more respectable than it is that’s what’s going to start happening.

I spent an evening with a college professor I had had and he told me he was teaching a course in science fiction, which flabbergasted me because he seemed, when I was in school, so opposed to popular literature of any kind. It so happened that he was generous enough to drive me 20 miles out of his way to take me to where I had to be and I was talking to him about science fiction on this drive. It became very apparent to me after about five miles of this 20-mile drive that he had not read it at all — what he was teaching, even — and didn’t have much intention of doing so. For example, I mentioned The Stars My Destination and he didn’t seem to be familiar with it. How can you teach modern science fiction without giving a nod to that book, which is considered by most critics to be the single best modern SF novel? There’s a school of thought that you start with The Time Machine by Wells and you go to The Stars My Destination, and those are the two you have to read. He didn’t seem to be too familiar with either one. That made me question the validity of what they’re doing at all. A guy gets assigned a science-fiction course because some department head says, “We should have a science-fiction course; who’s got a hole in his schedule? A guy who’s an expert on metaphysical poets? Okay, we’ll give him the science-fiction course because he’s not doing anything on noon Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.” I think they’re assigned just that arbitrarily.

Now if they bring in somebody from outside, somebody like Chip Delany, who’s vitally involved with this stuff, and use him as a visiting teacher, I can see that it could conceivably be a rewarding experience. But I don’t see how somebody who’s the proverbial two chapters ahead of the pupils is going to make them like science fiction or understand it or appreciate it, or maybe do anything other than turn them off it. And by extension that goes to anything from Elizabethan drama to Thomistic philosophy.

Was that the professor that you and Steve Gerber had?

Yeah.

It’s ironic that he detested popular culture, and look where you are now.

It’s ironic that he turned out not one but two comic-book writers. He hasn’t turned out anybody who’s done a lengthy, heavy, weighty tome of the John Barth variety. But he’s turned out two popular writers.

Did you actually ever learn anything from him?

He gave me enthusiasm. I don’t think he ever gave me a single piece of information, a single piece of data, but I think his enthusiasm for poetry made me want to read it. And by the way, maybe that’s what a teacher should do, maybe that’s how to teach culture. To get real enthusiastic about it. But obviously that precludes teaching it because you have an opening on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

How would you define a hack?

One who has no care for what he does. I don’t think it has anything to do with productivity. After all, Georges Simenon wrote over 700 novels and most of them are good. It’s just someone who does it solely for the money.

How would you rate your contemporaries?

[Catron] How many would you call hacks?

I’d have to think about that. Nobody I play poker with or see with any degree of frequency. I know guys who live in other states who in all evidence are hacks. Among my friends, I don’t think everybody hits the long ball all the time, but I don’t think it’s for want of trying, and anybody can have a failure. If I have a criticism of my contemporaries, it’s that they’re too involved in comics. Being a hack has to do with having no moral standards, largely. It was part of my agreement with DC that I will not be asked to write a story glorifying war because I don’t believe that war is ever a good thing and I would not feel comfortable with a military hero. I also don’t like to write romance stories. I did Millie way back when. That’s a skeleton in my closet, though. I think the way those stories are handled demeans what happens between a man and a woman.

Do you think DC’s war books are pro-war?

No, I don’t, no more than anything else that deals with the subject. I’m not attempting to justify this in any terms other than the fact that I don’t like military things and I’ve had a lot of experience with them. I have met one career officer in my life that I’ve respected. I went to a military high school, I was in ROTC in college and I put in my time in the Navy. I have a lot of acquaintance with it and I don’t feel like making any of those guys heroes. It’s as simple as that. If I were a total hack, sure, I’d write that stuff, because, what the hell, the check comes out to the same number of decimals.

What would you say to the possibility that superhero comics glorify violence?

I think it’s something I’ve lost sleep over.

Do you think Freddy [Wertham] was right, partly?

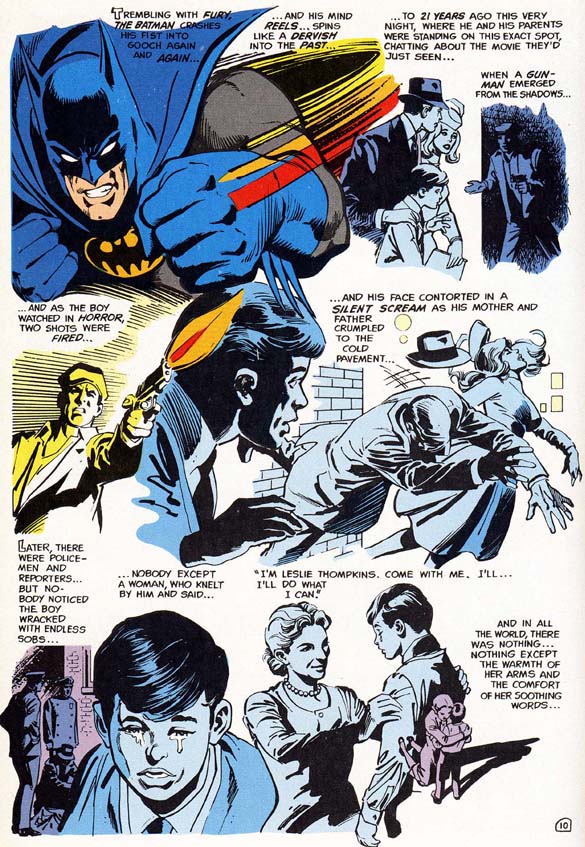

Well, Freddy oversimplified. The warrior has been a cultural hero in our Western tradition since before Homer. Even if I personally made a big stand against it, it wouldn’t change 5,000 years of cultural history. Warriors are heroes; men of action are the ones our culture has chosen to elevate to the status of Heroes. I try to work with that tradition. I don’t think I ever glorify violence. I’ve written a lot of scenes where people regret the fact that violence was necessary in a given situation. In one of the best stories I ever did, “There Is No Hope in Crime Alley,” the whole point of it is that the old lady who stayed in the slums and never raised a finger to anybody was a much greater hero than Batman — which he acknowledges on the last page. That’s the way I go with it.

written by O'Neil, drawn by Dick Giordano.

On the other hand, I believe boxing is an art form. One man against another with all the skills and intelligence that it takes to be a good boxer. I never met a stupid prizefighter. I think it’s an art form the way people like Ali and Norton practice it. What those guys do with their hands and their bodies is an art and I think that’s a valid thing. I’ve been involved in the martial arts and believe that’s an art form. So, I guess I’m not against violence per se; I’m just against senseless violence. I’m against artillery shells because they’ll zap somebody in a village with whom the guy who pulled the lanyard has no quarrel. I’m against high-level bombing where you knock out Dresden. I’m not against one man squaring off against another if they both feel like doing it and I try to get that into what I write. I’m not a knee-jerk pacifist. I used to be once upon a time. It’s another way I’ve changed.

What changed you? Anything in particular?

No. I just changed. I’ve lived a lot. I guess I’ve Lived — capital “L” — in the last seven years more than I did in the 30-some that came before.

How do you feel about your profession? I know at least one writer who’s embarrassed to say he’s a comic-book writer.

I’m not ashamed of it. I use a different form of my name — Dennis O’Neil — on other things, but that is a symbol to people that they’re not going to get Batman out of this. It’s going to be a very different thing.

Do you find that there’s a stigma attached to your name if you try to write for other markets?

Yeah. I found that there’s a terrible stigma attached to it in television. One of my big bitches — hey, we can get into the things Denny’s pissed off about — is that television people are absolutely unwilling to use comic-book people to do the comic-book shows. Alan Brennert did two Wonder Woman TV scripts. After he’d done the second one, he happened to mention that he’d once supplied a plot to the Wonder Woman comic book, and was told that had they known they wouldn’t have seen him the first time.

I find that there’s a terrible stigma attached to us by people who are doing the same thing we’re doing, only in a different medium. I don’t know why that is, except maybe it has to do with the pecking order. Everybody has to have somebody they’re contemptuous of. I did a television show [an episode of Logan’s Run] and I don’t think it was the 700 comic-book scripts that got me that assignment so much as the fact that I went in and did what I was supposed to, which was convince them that I could do the script. But I think they were probably more impressed by a handful of science-fiction stories that I’d done, which I consider inferior to the best of my comic-book work. I thought 10 years ago that that wouldn’t be true. We were getting respect. That’s something good that’s going to come out of this respectability, that nobody is going to have to be ashamed of doing comics anymore. But there is still a stigma attached to it. Even stoic, staid TV Guide ran an editorial saying, “Comic books are generally superior to the same characters done on television,” and yet there is a stigma attached.

You are considered some kind of subliterate because you do comics. I had dealings with a TV producer a couple of weeks ago and he was curious about comics, so I gave him a whole bunch of stuff. He called back a few days later, astonished that it was literate and had good stories and characterization and all that. I don’t know what he was expecting, but that’s a fairly common reaction.

Could that be economic?

It’s partly economic, yeah. If you get $8,000 for a script, obviously you’re superior to a guy who gets $400 for the same amount of work. Yeah. That brings us to the thing that I’m currently most angry about, having to do with the Superman movie and the TV shows, and that is that none of us guys who pioneered this form or who have been working in it or developing it are reaping any of the benefits, economically or any other way. Warner has released eight books in conjunction with the [first] Superman movie, none of which were written by comic-book people.

One was.

Which? Elliot [Maggin]’s novelization? Yeah. Elliot peripherally, but when they needed somebody to do the novelization of the movie, when they needed somebody to do the calendar, none of us got a shot at that. I’m very bitter and very angry. Not necessarily me, but somebody from comics should’ve gotten a chance to write some of the Wonder Woman TV scripts, the Hulk, Spider-Man.

It was a natural, logical assumption of mine when I went into this that if I worked well and worked honestly and did the best I could and didn’t fool around with anybody that there would be a natural progression, both economically and artistically, and it’s very frustrating to me that that has not happened. I know that I’m really going to sound like a crybaby now, but it seems to me that comic book people have done all this stuff and perfected this particular form of storytelling, and when there’s finally a chance to a) reach big numbers of people, which is something everybody who writes or draws wants to do — we all work for as big an audience as we can get — and b) get some sort of financial security, we’re not even considered. The publicity attending the Superman movie — the Newsweek story said that Warner also owns a company which is licensed to publish the Superman character as a comic book. That is the attitude of those people. It angers me both because it’s stepping on my toes and it demeans what I’ve been doing for a living all these years.

I’m staying with comics because I’m not ashamed of what I do. I get a craftsman’s satisfaction out of doing this thing well — I think it is something I do well — and I need to make a living. I have a lot more financial obligations at 39 than I did at 26. But in a sense — Bob Kanigher talks about the Golden Rut and I used to think he was exaggerating or whining or being a crybaby, and I see what he’s talking about now. There are assumptions when you go into anything that you’re going to be dealt with fairly. I don’t think that’s very much true. I think we’re used. That’s not to say any one specific person — I think both Jenette Kahn and Joe Orlando, to name two people, are not happy about the situation. Corporations simply don’t care about people.

What is it about comics people that they can’t put together a guild? You hear comics professionals screaming about the injustices heaped upon them all the time and yet they do nothing about it.

I’m not so sure we can’t put together a guild. I think, like democracy, it’s an experiment that has yet to be tried. Writers did it in the ’40s. The Writer’s League more or less forced publishers to give them twice the royalty rate on paperbacks. Every other group of writers has done it. Television writers, novelists have a strong —

Novelists don’t have a strong anything. But at least they get royalties and they own what they write unless they’re dumb enough to sign away the rights and some of them do that. I have worked for some pretty chintzy publishing companies and I’ve never found one where, if you made a point of it, they wouldn’t give you the copyright.

At this particular — to use a Nixonism — point in time, it’s not economically feasible to rear back on our legs and make demands because they don’t need us. It’s a depressed market, it’s just bad economics.

As for why they didn’t do it earlier: We tend to be independent people who like working alone. That’s part of it. Perhaps part of it is that sense of inferiority which has pervaded comics almost from the beginning. Until recently nobody would cop to working in comic books. If you were visiting your home town and your home newspaper had a “Who’s Visiting” column, you’d describe yourself as a journalist, or “work in publishing,” something like that.

One of the good things Jenette did was start calling it DC Comics instead of National Periodical Publications, which sounds like something that’s devoted to delineating the activities of obscure New Guinea tribes. That letterhead we used to have — “National Periodical Publications, Anal Retentive Publishing Company.” There was no fun that you got out of that. And Jenette had at least enough guts to say, “It’s comic books that we’re doing. Let’s call it what they are.” So, that sense of inferiority probably worked against forming any sort of viable guild.

The fact is that until my generation of comic-book writers, guys tended to be not formally educated very much and weren’t maybe aware of the clout they had. I mean, somebody like Bill Finger, who’s a great, raw talent, with no polish at all. I think he was just so happy to be writing that it wasn’t till the end of his life that he even got angry about the inequities that were leveled against him and it was much too late for him to do anything about it then. I think it’s a miracle that Siegel and Shuster got partially what’s coming to them. At least they won’t have to worry about money for the rest of their lives. On the other hand, if they had been in any other field and had created a character which is known in every corner of the Earth, they’d be many times millionaires. But they were a couple of young guys and they didn’t know from publishing, and they probably didn’t start out to be publishers. The guys who worked in the pulp magazines had the same deal. They signed over everything, including the rights to their first three children, to their publishers. So, when that stuff gets reprinted now it’s pure profit. There are no editorial costs involved at all. I think. Walter Gibson is an exception to that, but one of the rare exceptions. I doubt if Lester Dent’s estate gets any money from the Doc Savage reprints or the movie or any of that stuff. That’s just been true of pulp literature.

I would say that it’s not necessarily that way in book publishing. They’re not out to gouge you in quite so avaricious a way.

See, you’ve got to understand that popular culture is a technological and not an artistic phenomenon. Comic books existed because Max Gaines had presses that he needed to keep busy, and also they had recently acquired a quartering machine, which meant they could take pieces of newsprint and cut them into four pieces. It was a toy that they had, and Gaines had to keep the presses running for one of those obscure, arcane economic reasons that I don’t understand. So what did he do? He invented comic books as we know them. Then, having had the technology, he had to find something to fill it with. So he went out to find anybody he could get to tell a story and draw a picture. These people were delighted to be pulled from nowhere and given work, doing something they wanted to do. They didn’t think of themselves as artists or creators.

The same thing is true of the novel before that. The high-speed printing press is the reason we have popular novels at all. In the 19th century a bunch of things happened. After the industrial revolution, there arose a leisure class that was not yet the upper class. These were lower-class people who suddenly had time to read because they didn’t need to toil in the field 16 hours a day to eat. They only had to work 11 hours a day. That gave them some time to fill up to amuse themselves. At the same time, high-speed printing was invented. The logical thing: You put the two together. You’ve got a need to fill up those extra four or five hours a day and you have a technological device that can fill the need. Now you begin to go look for somebody to supply the stuff that gets put on the linotype machines. You find somebody that’s talented from the same social stratum as the people you’re aiming the book toward, which is blue-collar people, lower-middle-class people. This guy doesn’t come out of the cultural tradition. His grandfather didn’t know how to read at all. He doesn’t think about the fact that there are royalties and rights due to him as a creator. He thinks that this is a hell of a lot better than working in the factory for 11 hours a day. “And I get paid better than my brother who’s working in the factory.” That’s as far as his thinking goes. Therefore, he signs away all rights to everything. Publishers get used to this happening. There arises a tradition of it happening that’s carried through until recently. It’s a technological-sociological phenomenon. I think that explains why these people never demanded their rights back. And people like me, we came into this tradition, we came into a structure that had been set for 40 years, and no one person can fight it.

It’s the most absolute truism in the world that technology always precedes art. Always. No painter ever said, “Well, I want to make a portrait of the Mona Lisa, so I’m going to figure out a way to do this.” He said, “I’ve got these paints and this stuff, and what can I do with it?”

That always happens, and it’s something it seems to me that nobody who teaches this stuff in college ever acknowledges. Going back to the cavemen, they had to have the wall and the sharp stone before they made the pictures. And it’s especially true of things like comic books, which are low-common denominator art.

So, basically, comics are just bottom-of-the-barrel publishers.

Yeah, and the bottom-of-the-barrel creators, people who did not come from a tradition of demanding their rights, of even knowing what their rights were. People who were basically uneducated, maybe enormously talented, but not formally educated, so they didn’t know what was coming to them and they didn’t demand it. And Len and Marv and me and everybody have inherited that and that’s where we’re at.

You’ve said that the guy who could fix a carburetor is as valuable as a writer or a musician. Just as valuable in what way?

He has something that he does that is valuable and necessary and takes a certain set of aptitudes. Not everybody can do it. The world would not function without that guy, therefore he’s as valuable as I am, or as valuable as Mahudin, or as valuable as Gore Vidal or…

Maybe more valuable? Can’t the world function without your comic books?

Yeah, in that sense. If the Bomb went off tomorrow and there were only a handful of us, my survival would not have a very high social priority. The guy who knows how to make the fuckin’ engine go — him you’d have to save. Yet I think I’m a valuable member of society because I do something that people need. They need to hear stories.

What is the value of culture, then?

It makes us civilized; it makes us something other than animals.

Isn’t that its value, then?

That’s a very complicated subject that, again, people have been debating for 12 centuries. But I can say that when people get past subsistence, when they know that they are going to eat and have something to keep the rain off them, they need me. They need the shaman, the tribal storyteller. I have an image of myself, if that Bomb did explode, squatting on a hillside surrounded by children telling them stories which is, after all, how I started out. When I was seven years old, I told stories to the neighborhood kids. I wasn’t the best football player, I wasn’t even the smartest kid in school, but I was the one who could tell them stories, and that’s what I’m basically still doing. That’s my function. I don’t like it always, I’m uncomfortable with the role, and I’ll slug anybody that calls me an artist.

Why?

Because that carries all the cultural freight where I’m supposed to be uplifting people. I don’t want to do that. I don’t know if I’m capable of it. In my best moments, I can amuse them.

Another head change… This occurred to me while I was reading the Neal Adams interview you ran. Actually, it occurred to when I was talking to Harlan [Ellison] last Thursday, and he had had dinner with Neal, and evidently they had been arguing about using the medium to Change The World. Evidently, if Harlan is to be believed, Neal was coming down on him for not trying to use television… And I thought, Jesus, do I want to live in a Neal Adams world? No. I don’t at all. If I lived in a Neal Adams world, women would not be equal to me; I would have a very authoritarian attitude toward children; I would believe quantity equaled quality; I would value a 747 above a bicycle. (I believe a bicycle is the most beautiful machine there is. It’s simple, it’s economical, it does exactly what it’s supposed to do, and it doesn’t hurt anybody.)

And conversely, maybe someone wouldn’t want to live in my world if I became King-God tomorrow. Maybe the system we have, as dumb as it is, is better. So, by just taking that one extra little step, I have to believe that I don’t have the final answers either. And maybe I should limit myself to squawking about things that I perceive as inequities and trying to let solutions work themselves. If you recognize the problems, maybe the solutions will come. I’m saying I’m a hell of a lot less of a proselytizer than I was at one time. I mean, the Reverend James Jones had solutions to things, right?

This Synanon dude had solutions, and look where both of these guys ended up in a very short period of time. They ended up insane. They ended up corrupting and destroying the very people they set out to save. That seems to be the way of it. As intrinsic as it is to human nature to hear stories, it also seems intrinsic to human nature to abuse powers. Who are the great villains? Hitler was probably the greatest villain of all time. And Mussolini — and they made the trains run, by God. I get very itchy now when people come on very strong about changing the world. And even in the peace movement, which I was close to for a time — my FBI file is probably like that, [holding up his hands] not because I ever did anything, but because I testified a lot — and I saw those guys get on fantastic ego trips, which partly defeated what they were trying to do because they got into squabbles with each other and they forgot that LBJ was the enemy, not the guy who was running the other faction of the peace movement. Same thing seems to have happened in the feminist movement. Ms. magazine is notorious for ripping off women writers. In the best of times, it seems that people catch themselves in time to keep from going completely around the bend. If they don’t, they’re James Jones. It’s another reason I think I want to deal with me — rather than you — first. Even Shaw, who is maybe the greatest advocate of socialism who ever lived, said somewhere, “The trouble with looking out for Number Two is you don’t really know what Number Two needs or wants.”

[Catron] You wrote something on Manson, didn’t you?

Actually I was accused of writing specifically about Manson and what I intended was — I saw within the peace movement and within the comics culture a lot of fascist stuff beginning to happen. I don’t know why it happened to come out looking so much like Manson, but he was one of three or four people I had in mind when I was doing that. I also think we copped out on that and used drugs as an explanation. But, you don’t need to use drugs to explain that people follow charismatic leaders. They did not put LSD in all the reservoirs of Germany in 1932.

Why do you think people follow cult leaders?

Jesus, I don’t know. I could offer guesses, but they would be no better than yours or anybody else’s. Personally — looking at me because I can’t talk about you — I occasionally feel so insecure about my life that I wish somebody would come along with a neat set of answers. I keep waiting for a telegraph from God and if God happened to manifest himself in the form of a very charismatic human being who calmed my fears, offered me a program, and made life simple for me, I’d be tempted. In modern life, you see that more and more because the nuclear family is disintegrating and whatever is good or bad about that, it makes people tend to be scared.

Could you see yourself joining a cult?

I’m not a joiner. I don’t even belong to the Writer’s Guild. I don’t know why I’m not a joiner. I’ve never figured that out about myself. But I don’t think so, merely on the basis of past history. I had to be talked into joining ACBA [Academy of Comic Book Artists], and really talked into serving on the board. And I declined the chance to run for President of the organization when I was nominated.

I can understand people wanting to follow somebody who has answers. I live a thousand miles from my nearest relative — except for my child — and I feel sometimes at 3:00 a.m. that this apartment can get awful big and awful lonely, and I would like very much to have somebody around that had to like me because I was their relative, somebody I didn’t have to perform for. A lot of people are exactly in that situation. Or if they do live next door to their parents they’re estranged from them. That happens more and more. It’s a very natural thing. We’re not solitary creatures. We need to belong to something.

I’ve written a lot of stories about alienation. I guess one of the reasons I respond to Batman as a character is I think he’s basically alienated from everything except his obsession. In “Elseones” [one of O’Neil’s short stories] I wanted to write the ultimate alienation story — a story about an alienated alien. That’s because I guess I have felt alienated from this society from very early on. I’m at a loss to explain why. I had a normal childhood, I went to normal schools, and I’m currently on very good terms with my parents.

What do your parents think of your comic-book career?

I think they’re reconciled to it now. I think they didn’t understand what it was all about. I don’t think that any middle-class person can quite understand what it is a writer does.

Why is that?

Because sitting down and making up stories is not work. You’re not building or selling something. When I was in newspapers, they could understand that and it was fine. They read newspapers; they knew what it was. I don’t think they quite understood what I was doing in New York. I think they realize now that what I’m doing is work, it’s honorable. I mean, I’m not pushing dope or mugging people.

Roy Thomas leaving Marvel is to your mind fairly inconsequential. Might that be because the comics companies have diminished the individuality of artists and writers in the field to the point where they are an interchangeable commodity, and it doesn’t matter where they go or what they write?

That’s a complicated question. Here’s a sketchy answer. In general, the artists and writers are far more important than they’ve ever been in the history of the medium because for a long time, you’ll remember, we didn’t even get bylines. I’ve published a lot of stuff that went out without bylines, and I’ve been in the business a relatively short time.

The top 10 artists and the top 10 writers may very well be interchangeable for all practical purposes. Len [Wein] and I were talking about that the other night. I am now writing one of his characters — Dominic Fortune — and he’s writing one I’ve been associated with — Bat Lash. I don’t think either character has suffered because I think Len and I have about equivalent skills. I don’t think that any casual reader — meaning a reader who does not pay attention to bylines, which is most of them — is going to notice. I think a character will suffer from being taken from somebody of considerable skill and given to someone of lesser skill. But there is a certain plateau that people reach after a while and if they keep their heads intact and they keep their sanity and if they maintain the ability to function at something near-maximum effectiveness… well, you know, when Roy takes over Batman, it’s going to be a different Batman than mine. I question whether it’s going to be substantially better or worse.

Well, it might not be better or worse, but it might be different and that’s the important thing.

It’ll be different and that’s one of the little joys of the medium.

But, the question is: Will it be different? You just said Len is doing Bat Lash and you did Bat Lash…

Well, we’re talking about some Platonic ideal of quality I guess. Yeah, Len’s Bat Lash is doubtless different than mine, Len’s Batman is different than mine and we’ve talked about that. But, it’s probably just as enjoyable. It will be different, but I suspect that — if there were some way to measure an enjoyment factor, given 500,000 readers, it would probably come out to be very close.

I wasn’t talking about deriving an equal enjoyment out of different writers or artists. I was talking about the sameness that contributes to that interchangeability. You can derive an equal amount of enjoyment out of Shakespeare and Ibsen, but that doesn’t mean they’re interchangeable.

The institution of storytelling is vital and important to our culture and any culture. It exists in every culture that we know about and in some of them, it is on a par with religion to the collective consciousness of the tribe. I think storytellers are tremendously important, any kind of storytellers to any kind of civilization. I question that any one story or even any one storyteller is that important. I don’t know that modern drama would be a lot different if Shakespeare had never existed. I’m prepared to say almost unequivocally that there would be virtually no change in the modern detective story if Conan Doyle had never existed. So it is possible to venerate the institution and still become a little chagrined at the freight that is put upon anyone given manifestation of the institution.

Again, you’re sort of diminishing the individual artist from which art comes.

Why?

Because you’re saying no artist is that important.

In the broad overall, comprehensive picture, no, I don’t think any of them are and yet that does not mean —

But haven’t they added something precious to the world?

Sure.

Without which the world would be poorer?

Unquestionably. I have certain authors whose books I buy, in hardcover even, and my life would be a lot poorer without them. But, that’s my life. The world as a whole would not notice their absence is what I’m saying.

I’m sure that’s true of any author, but I’m not sure what that means.

It means that it’s possible to get too excited about things that don’t have a lot of consequence in a big picture. I’ve noticed that people tend to get a lot more excited about their pleasures than about their livelihoods. People can come out of a movie vehement in their anger at some poor director or filmmaker, and it’s a kind of vehemence that they seldom display at their politicians or their children’s principals. I don’t know why that is, but I notice it in myself. When I have an ill feeling about a piece of art, it’s almost inevitably more intense than my ill-feeling toward a political situation. Possibly because it is the child in me that responds to the art, any art from a Double-Bubble comic strip to a Beethoven symphony. It’s that side of me that responds and that side of me tends to get more excited about anything than the calm, mature person that has to deal with politics or family matters. So, I understand why — I think I understand — why all this heat comes from comic-book stories, why people can get so vehement about something that really does not affect their lives.

I don’t think that in any way diminishes my regard for the dozen favorite writers I have. I mean, my God, I read four novels a week, and probably see four to five movies a week. I’m as into it as anybody on Earth, just about. A major portion of my life has to do with art. And a major portion of the joy I get from life has to do with it. But, if John D. MacDonald had never lived I would substantially be the same person, and I might have found somebody else to fill that vacuum that he fills in my life. I don’t know. But that’s the easiest example I have of some whose work I always enjoy.

That’s true of any artist or writer, that you can live without him.

That’s all I’m saying.

That’s inarguable. You talked about storytelling and how important it is to a society, but that doesn’t speak to the differences to a society of good stories and bad stories.

I don’t think anybody has formulated an aesthetic for the ages yet. I mean, I think aesthetics is fascinating and I will willingly read anything that anybody has to write or listen to anything that anybody has to say about it. But, I don’t want to get into the question of good and bad because it’s so muddled.

Yes, but it’s important.

Yeah, I have a gut feeling that it’s important, but I’d be at a loss to say exactly why. I do know that, for example, literary fashions come and go. Dickens seems to be respectable now, he was absolutely not respectable when I was in college. So to some degree, people’s perceptions seem to change about what is good or bad. I don’t know anybody who has managed to establish an absolute yardstick, and in fact, some very serious thinkers disagree violently. Plato would have eliminated Homer from the Greek culture as being morally pernicious. Nietzsche would have eliminated approximately 90 percent of all art, particularly 90 percent of all music. Strauss was, in his time, vehemently condemned for the waltzes. Obviously, in the case of Nietzsche and Plato, they were very respectable thinkers who were passing those judgments. I don’t want to get into aesthetics with a 10-foot pole. I have my own standards of storytelling. They are pretty much mine, but since they seem to find a large area of response out there in that a lot of people apparently like to read what I write and edit, I suspect they are the standards that many people hold.

But, do people hold standards at all?

Oh, I think the average reader picks up a comic book and then puts it down x-minutes later, thinking Good or Bad and does not delve into aesthetics. I think that’s generally true of almost any entertainment.

Well, that points out the utter lack of discrimination among the public, which reflects our state of popular culture.

Yeah, but it’s an evolving thing. I think it does need to be looked at and commented on. I just think we have to be careful when we talk about elevating the general taste because elevating it to what comes to mind. As I said, that gets changed every 10 years or so. John D. MacDonald is an example. The first book of his that I read I was very angry that somebody had lent this to me and recommended it and wasted my time. That was when I was about 22. A few years later, I read, for whatever reason, a second book and liked it very much. And later went back and read that first one and liked it. So, my tastes changed.

What were your objections? How have your tastes changed?

I think I had a snotty college kid’s attitude toward pulp fiction. I think I objected to something about his style, some petty thing. I might still object to it, but now in the context of everything else that’s in the book, I would consider it beneath mention.

I once saw an English professor, a guy who taught English in an upstate college, pick up a copy of one of Vonnegut’s books, Cat’s Cradle, and read the first page and the last page, and not having read anything else of Vonnegut’s and on the basis of that, pronounce it dreck. Then there is Denny’s Adventures in Professorland, meeting some of my taste-formers now on a social level where I have some credentials myself, and being appalled by what they don’t know about what they’re teaching.

Cont.