Dapper and compact, soft-spoken and full of erudite conversation, R.O. Blechman is the single most cosmopolitan cartoonist I’ve ever met. He could easily be a character in a Henry James novel. Appropriately enough, his art owes a debt to that mid-century mansion of metropolitan wit, Harold Ross’ New Yorker, where James Thurber and William Steig returned cartoons to their roots in doodling. Blechman’s scraggly-lined people, so minimal that they are barely visible, show what happens when the tradition of Thurber and Steig is taken to its extreme. All excess is removed and every drop of ink counts.

Born in Brooklyn in 1930, Oscar Robert (“Bob”) Blechman made his mark as a cartoonist at a young age, with his now classic work The Juggler of Our Lady coming out in 1953, not long after he had graduated from Oberlin College. One of several proto-graphic novels from the late 1940s and early 1950s, The Juggler of Our Lady earned praise for its heartfelt story and touchingly spare art. It was made into an animated short in 1958.

Blechman has gone on to distinguish himself as a magazine cartoonist (appearing in everything from Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug to Esquire), animator (he directed the 1984 PBS special The Soldier’s Tale, which won an Emmy), advertising mastermind (his many ads, including the 1967 Alka-Seltzer commercial, are a fixture of post-war visual culture). In recent years, he’s authored a kid’s book (Franklin the Fly) and a very astute book of advice for freelance creators (Dear James: Letters to a Young Illustrator). In 2009, Drawn and Quarterly published Talking Lines: The Graphic Stories of R.O. Blechman, a sturdy and sumptuous collection that usefully gathers together fugitive pieces done over several decades. This month, he’s being honoured with the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Cartoonist Society.

I interviewed Bob Blechman on October 30, 2009 when he was in Toronto to give a talk with Seth at the International Festival of Authors. My only regret in meeting Blechman was that I didn’t tape our dinner table conversation, where he ranged even wider over his remarkable career.

R. O. BLECHMAN: I brought a copy of Dear James for you.

HEER: I actually contacted your publisher Simon and Schuster ahead of time and got a copy. It’s actually a very nice physical book as well.

BLECHMAN: It’s OK, yeah.

HEER: Nothing like Talking Lines.

BLECHMAN: No.

HEER: I don’t know how familiar you are with Drawn & Quarterly, but their other books are all very nice physical objects. I think that’s where Chris Oliveros really distinguished himself.

BLECHMAN: Yeah.

HEER: All the books by Seth and many other cartoonists are all really beautiful objects.

BLECHMAN: But my experience with him is that he is a first-rate editor. He was very involved in the selection of pieces, and sometimes he did things that I would never think of. For example, the very last piece in the book I thought would be “Georgie.” Which is a dark piece. So Chris thought, “Hey, let’s bring the reader up a little bit” so he thought to include…

HEER: "Looking in the Mirror"?

BLECHMAN: Yes, it’s nice, because number one, it’s autobiographical. And number two, there’s a little humor and lightness which God knows the reader would like [Heer laughs] after having gone through the harrowing adventure of this poor dog.

HEER: Yeah, that’s right.

BLECHMAN: It’s typical of how Chris has been very instrumental in the shaping of this book.

HEER: Yes. I totally agree. It’s interesting. There’s another magazine that was doing a profile of Drawn & Quarterly and of Chris. I told the interviewer that Chris really sort of harkens back to the older style of editors who really creates a list and really does a lot just in terms of selecting stuff and by editing his list. He reminds me of James Laughlin who did New Directions.

BLECHMAN: Oh, wow.

HEER: You know, like that sort of publisher.

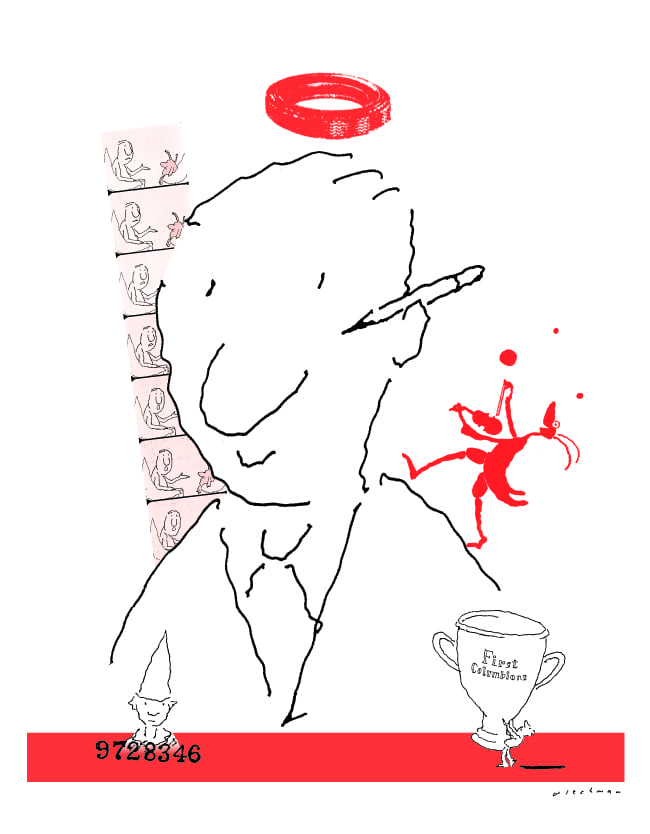

BLECHMAN: My hero. I love New Directions. I was about to say, I think Chris is the Maxwell Perkins of the graphic novel industry. He, again, was extraordinarily helpful and I must say, I resisted this cover because I thought it was so Steinbergian. But I’m so glad that, finally, it was produced. It only happened because I couldn’t come up with my own design. I love to do design work, but I couldn’t think of anything better than that.

HEER: I don’t think Steinberg is anything to be sneezed at. That’s actually one of the questions I had.

BLECHMAN: Yeah, sure.

HEER: Was going to be pursuing this. Obviously, that New Yorker generation, not the first generation, like Peter Arno or Charles Addams who are very lush, but the second generation of Thurber and Steinberg. You never mentioned Steig.

BLECHMAN: Yes I did.

HEER: Oh, you did mention Steig.

BLECHMAN: Let me think about it … No, I probably didn’t. I probably didn’t.

HEER: Those are the three that come to mind when I just look at your work.

BLECHMAN: Well, it’s interesting. I would say there are maybe four generations. The first would be the work of the first cover artist whose name I forget.

HEER: Rea?

BLECHMAN: Yeah, yeah. And the editor …

HEER: Ross?

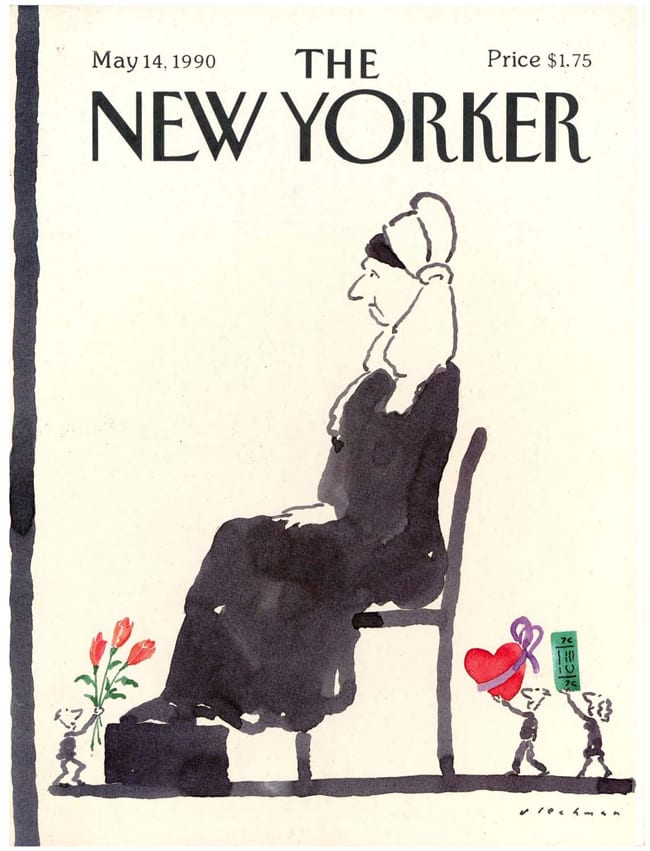

BLECHMAN: At least I remember your name and my name, I can’t remember anything else. But Ross told his writers to look at the work of Rea Irvin and then model their own stuff after him. But, be that as it may, there was a look in the ’20s and ’30s that was supplanted, if you will, by the look of the ’40s, which was maybe Peter Arno, Charles Addams, Thurber and so forth. Then there was a look of the ’50s and ’60s when Lee Lorenz was there. The stuff became quite anecdotal. All those three name ladies from Long Island. [Heer laughs] Then there’s the Francoise [Mouly] book which is pretty much the Art Spiegelman kind of in-your-face graphics I think there were all these stages. I was involved in the third stage, and had one cover in the fourth stage.

HEER: Oh, OK.

BLECHMAN: And that was it. But so be it.

HEER: When did you first become aware of The New Yorker?

BLECHMAN: Oh, God. Early on, my Dear James talks a lot about that. When it was first starting out, I would submit cartoons to them. And everything was rejected, but Dear James goes into the whole thing, so why should I repeat it if you have Dear James. They rejected everything, and then finally they accepted something with a hand-written letter. So I didn’t do any work for a long time … No more submissions because I was afraid I would be dropped a notch to the printed rejection slips.

HEER: Yeah, but in terms of the ages you were talking about. It was very much like it was the second age of Thurber that was when you became aware of the magazine.

BLECHMAN: Oh yeah. It was during the very early ’50s … late ’40s. I never read the magazine that much, but I sure as hell admired the covers and the cartoons, both. And now, by the way, what is very interesting about The New Yorker is the illustrations, which they never had before Francoise [Mouly]. That’s really done primarily by Chris Curry. I’m so delighted I can think of the name. I’ve forgotten so many. Chris Curry. And she has a whole new look, which is very much the look of graphic novelists, I thought.

HEER: That’s right. A lot of the Drawn & Quarterly people, Adrian [Tomine]. Chris Ware, Seth — they’ve all been incorporated into The New Yorker now.

BLECHMAN: Which is a great look, I love it. As a matter of fact, Seth had something in today’s New York Times.

HEER: Oh yeah, I saw that. It’s interesting, because he is also someone who’s a generation after, but he studies the classic New Yorker and incorporated it into this style. So you were more aware of the magazine visually rather editorially?

BLECHMAN: Although I’m a great reader. I just happen not to have read all that much of The New Yorker, but occasionally when I do read it, I like it a lot. But again, I have so many books and other magazines and newspapers to read that I draw the line at … Well, occasionally I’ll read something in The New Yorker, but it is not my primary reading matter.

HEER: Now, am I wrong in thinking that initially, not from you, but from other cartoonists, there was initially a resistance to the Thurber style.

BLECHMAN: Oh, no. A resistance? God no.

HEER: I always have this sense that people, a lot of the classic cartoonists -- the Peter Arno -- types who put a lot of sweat into that would look at Thurber and say …

BLECHMAN: No, I don’t think so. They admired him. Actually, it’s rather Robert Mankoff who on a radio interview, I’m told, dismissed, extraordinarily, Thurber’s artwork. Which is kind of amazing. But, no, I think they all loved it. There was so much wit and humor and intelligence and philosophy in his stuff that they may have forgiven the primitive drawing style. There were a lot of artists in the ’20s and ’30s who drew in a similar style. There’s a guy called Hendrik Willem van Loon. That so called naive look was not unpopular when Thurber was functioning. Thurber never thought of himself as an artist, he would just do pencil drawings and then other people would pick them up off the floor or the garbage can and ink them for production.

HEER: That’s right. I think if it wasn’t for E.B. White, Thurber wouldn’t have become a cartoonist, which is interesting. The reason that I am asking is to kind of get to the question of style. It sort of comes up in Dear James and maybe a little bit in Talking Lines as well. It’s an interesting thing that when an artist starts out, he or she often imitates what’s around them and experiments in different forms until he or she finds that voice, that particular thing. Maybe I asking in a roundabout way, but I’m trying trying to get at that question of style. What were the voices you practiced before finding your style?

BLECHMAN: Well, I’ll just answer this question elliptically. My very first job was for a defunct magazine called Park East. There’s no contemporary equivalent. But I was told, “give me a page of drawing and I’ll give you a hundred bucks.” And I thought, God, the guy is actually going to pay me one hundred dollars for my drawings? So my first ones, which maybe was my first published work, that was in 1952 or 1953, was done in a stitched line technique. Which was very popular at the time, it was kind of innovated by Ben Shahn and taken over by David Stone Martin — I think was the guy’s name. And even, believe it or not, Andy Warhol when he was first starting, he did the stitched line technique. But my work was done in that style. But part of it, I now remember, was that I was given another job. I think it was for the Jewish Theological Seminary and my stuff was very tight because I didn’t think that a loose technique was appropriate. And then, how did I come to my style? I think it’s a mystery, I don’t know if any artist can ever say how. But it was a gradual, very slow, laborious process in which a lot of it is natural, it comes out of you. But a lot of it is arbitrary and artificial, because you say, hey I feel comfortable with this, I like it, I’m going to explore this. I did a lot of my drawings in pencil because I thought that the pencil line was nice. I would soon realize that the pencil line was not so nice and so I started doing work in ink. I don’t know, I just don’t know how I came across my style. It’s not that I copied Thurber or copied Steinberg even though there may have been Steinbergian elements in my stuff.

HEER: Maybe to go back a little bit; you said that you hadn’t intended to be an artist originally. Although you went to a …

BLECHMAN: Music and Art High School. I didn’t intend to go for music and art. I kind of slipped into it. As a matter of fact my art teacher wouldn’t even give me a letter of recommendation. She basically said “Look, I can’t say anything good about you, and I won’t say anything bad about you so I won’t say anything.” But, it may have had to do with the fact that my neighbor was a French refugee and a painter, a bohemian, beautiful blonde young lady and I guess I was in love with her and …you know, “in love.”

HEER: You had a crush?

BLECHMAN: Yeah, I had a crush on her. And maybe, and this only occurred to me a few years ago. Maybe my desire to go to art school was a way of identifying with her. And even when I went to art school, I didn’t think of myself as an artist. I was surprised when I was accepted.

HEER: That’s interesting, that reminded me of something. We have an acquaintance, or a friend in common, Leanne Shapton.

BLECHMAN: I’ll be damned. Very good.

HEER: Yeah, and Leanne mentioned to me, we were talking about you, and she described you as a Francophile , which comes through in your work maybe a little bit. Like, there’s a little bit of maybe Folon in you …

BLECHMAN: Oh, I love his work. Love it.

HEER: So maybe the roots of the Francophelia go back to...

BLECHMAN: Yeah, that’s interesting, and also to the fact that, when I was a kid, there was a neighborhood theater which played French films that knocked me out. Plus the fact when I was about 12 years of age, the junior high school gave two language courses. And this really dates me. One was Latin and the other was French, can you believe it? The good students were given Latin and the students like me were given French. So maybe there was that. But you know, I think it’s kind of arbitrary where you’re born geographically. I think your temperament lends itself geographically to one culture or another.

HEER: Maybe the heyday of a type of American Francophelia because of the war and the alliance. And the power of French culture. Reading people like Sartre and then all these American artists who lived as ex-patriots. That sort of has disappeared from the culture.

BLECHMAN: Oh, very much so. Now the French come here.

HEER: By the way, that school you went to, I don’t know if you know this, I believe that was Harvey Kurtzman’s school as well.

BLECHMAN: Yes it was. I wish I had known Harvey well. I kind of regret it. But at the time, I didn’t appreciate his stuff because I didn’t like Mad magazine and I didn’t like comic books. I thought it was a cultural level below me. It’s a terrible thing to say, but I liked Harvey a lot. And I didn’t know his work. There’s this wonderful book that Abrams came out with. My first insight into what Harvey was all about was when I attended his memorial service and Art Spiegelman gave the, I wouldn’t call it a eulogy, but the … well, he talked about Harvey and I realized, “Oh my God, this guy was a very important artist,” and I didn’t know it at the time.

HEER: Kurtzman is a bit of a tragic figure in the sense that he was often working in venues that were beneath him. He had this creativity that didn’t have an outlet. So Mad comics was very good, but a 10¢ comic book full of garish colors, and then later he tried to find a creative outlet — that was The Jungle Book — which never took off. And then he worked for Playboy, which is … you know.

BLECHMAN: Humbug is a swell magazine. I really like it. You probably know the two volume series.

HEER: Yeah.

BLECHMAN: What a work of art that is.

HEER: That’s great; the Humbug stuff is really great, and it’s interesting with you that he was trying to find … to create a genre. To try to find a venue for his creativity through Mad, through Humbug, and through The Jungle Book, which I think you did far more successfully with the Juggler of Our Lady. It seems like there were several visual artists of the era who were trying to do comics, but not in the comic-book form and not in the New Yorker form.

BLECHMAN: Yeah, that’s true. I mean, I was lucky as hell. The story is that in college I took a course in humor and so for my year-end thesis, I did a book, Why Rome Fell. I guess it is what you’d call a graphic narrative. So when I got out of college, I showed the book around, and one guy who had an art studio and who did a lot of book jackets for Henry Holt said ‘Hey, you should show this to Henry Holt?’. Henry Holt said, “Well, we can’t publish this sort of thing” — probably said this to get rid of me — “but if you come up with a holiday-themed book, we’ll consider it and look at it.”

So, I went back to my house and called a friend of mine and said “Hey” — I’m trying to think of the guy’s name now — “Paul, do you know any good holiday literature?”

And he said, “Yeah, there’s this medieval legend called ‘The Juggler of our Lady,’” and he told me about it. And I got the book the next day and that night at my kitchen table, I wrote and drew the whole damn thing. Then I brought it to them and they published it. I was amazed. It was just luck. I had to see this art director, luck they decided to get rid of me by giving me a holiday-themed thing, luck that I called my friend Paul, you know. Luck, luck, luck, and bad luck, bad luck, bad luck. You know? All these links in one life.

HEER: Yeah, it’s interesting the medieval theme, because you’d mentioned in one of the books was Alexander Nevsky was one of your favorite movies in college. I had thought that that might be one of the inspirations, but obviously, I guess not.

BLECHMAN: No, no, no. Not being crazy about movies, but who the hell isn’t crazy about movies? Who wasn’t and who isn’t? I mean, it’s the major art form, isn’t it?

HEER: Maybe we can also talk a bit about the animated film that came out of the book? Because I was talking to an animation historian, Mike Barrier and he made an interesting claim, which is that even though it’s done by Terrytoon and Gene Deitch was …

BLECHMAN: The director.

HEER: He said that it looks more like a Blechman movie than a Terrytoon movie.

BLECHMAN: Well, since it was based on my book and since I was the so-called consulting director, how could it not be mine? It was and it wasn’t. I mean, I didn’t like the crayon technique and other than that, that bothered me. I thought it was an OK film. It’s a good film. But, it was done not by Gene Deitch, he was kind of the supervising director. It was done by a guy called Al Kouzel and he was a good filmmaker, good art director. But, you know, they also had Feiffer on staff and did one of his stories. He was a storyteller at the time, in the story department …

HEER: Yeah, Munroe, wasn't it?

BLECHMAN: Ralph Bakshi was there at the same time. And you have to remember, that Terrytoons was bought by CBS and CBS hired Gene Deitch. Gene Deitch and I worked together in an animation studio called Story Board with John Hubley — an ill-fated enterprise. My very first job ever was being a storyboard artist for John Hubley, and incidentally, in today’s Times, there was a review of Finian’s Rainbow. Did you know that John Hubley had done a storyboard and financing for Finian’s Rainbow? Had scored it with Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra? It was all set to move, but there was a guy called Senator McCarthy who was on his patriotic, or unpatriotic rampage and the minute the investors learned John Hubley was a radical, withdrew the funds. Tragic. It might have been a great film. It had all the ingredients. Very sad.

(continued)