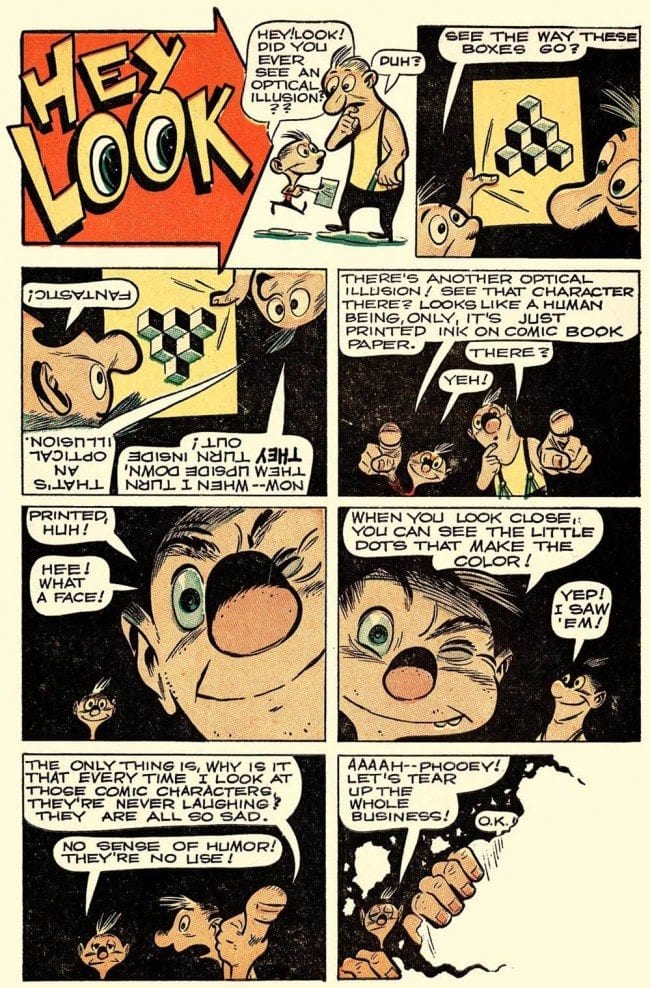

Comics are a self-aware art form. We can see this in a Harvey Kurtzman Hey Look! from 1948.

Isn't this great? This classic one-pager begins with a discussion of illusion and ends with a startling reversal in which the characters in the comic are “real” and we (the readers) are merely printed, ben-day-dotted images on paper. The “real people” rip up the paper that we, the readers are printed on, protesting that we aren't amusing enough. Along the way, we get an inverted panel, upside-down dialogue, an image within an image, and virtuoso foreshortening.

In this page, Kurtzman is a magician who tells us he will reveal a secret to a trick and, in the process of spilling the beans, he creates an even more astonishing illusion. The “how” no longer matters, because the effect has done something to our minds that is far more profound, flipping our perceptions inside out, like the stacked cubes in the optical illusion.

Perhaps comics tend to be self-aware because the very act of making a comic requires intense focus on the building blocks of the form. Anyone who has sat down to create a comic knows there is a surprisingly complex decision tree that must be worked out.

It can go something like this: What's my story? How do I break it down into little pieces? How many pages? How many panels per page? Will they all be the same size and shape, or different? Will I tell the story with narration, or dialogue, or a mixture of both? How is it going to be printed? What size should I draw it at? Will I use a computer to letter or color, or touch up the art? Which of the hundreds of drawing tools available should I use? That’s just for starters. The list can go on and on.

Part of the greatness of a particular comic has to do not with how well the artist can draw, but with how thoughtfully and creatively they have worked with the formal elements. As with artists in other mediums, accomplished and dedicated comics artists assemble their own unique combinations of these building blocks – and that's called style.

The masters of the form have sometimes incorporated self-awareness into their work, creating experimental, playful comics that have stretched the form and opened up new possibilities. By no means a complete account, here is a glance at a few examples of comics that have pushed the limits.

I am sometimes asked for my definition of a comic. I have blithely given the following definition: “A sequential graphic narrative using words and pictures.” That definition has worked pretty well to explain to someone who typically doesn’t read comics. You know the type. The person who sees a superhero or Garfield in their mind when they hear the word. But, of course, I’m now going to show just how wrong that definition is. Let’s start with the “words” part of the definition.

H.M. Bateman (1887-1970)

H.M. Bateman was a British artist who was well published and appreciated in both his home country and in the United States. He could draw exquisitely humorous figures and had a gift for outrageously pushing a set-up far past the point where one would expect the gag to stop. Bateman’s comics usually have no dialogue or narration., which asks the question: Do comics have to have words?

Take Bateman’s four-pager from 1920, “Possibilities of a Vacuum Cleaner.” We start with our man walking into his living room, in which we see a footstool, cat, and piano. He sees his maid with a vacuum cleaner and gets an idea. He buys an extra-large attachment for his vacuum cleaner and in short order the vamped machine has inhaled his footstool, cat, and piano. And the maid!

On page two, our man (one could not call this psychopath with a household appliance our “hero”) ventures outside with his machine and proceeds to remove anyone and anything in his path. Pet walkers, bike riders, and even a double-decker bus – they are sucked into the maw of his vacuum cleaner.

The mad consuming continues on page three, escalating to the serious tonnage of a steam roller. And here comes The Law. A crowd (mercifully unconsumed by the insatiable machine) has assembled and this has attracted a policeman. Though there are no words, you know that as he walks up to our sucker in a seersucker suit he is saying, “Here! What’s all this, then?”

It’s clear this anti-social maniac must be stopped. The army is called out, but their fusillade of bullets disappears into the vacuum, followed, of course, by the army itself! Bateman ends the narrative perfectly, with our man falling victim to his own creation. There’s very likely some sort of cautionary message about the downside of consumerism, or the dangers of blind technological progress in all this – but who cares? It’s funny as hell. Just look at those drawings!

Bateman’s “Possibilities of a Vacuum Cleaner” is merely one example of dozens, if not hundreds of outstanding comics that are wordless. In 2014, Art Spiegelman and Philip Johnson presented several examples, including a great Bateman, in glorious fashion with their multi-city WORDLESS! show. (I reviewed the show in this column, here)

Rube Goldberg (1883-1970)

Ruben Lucius Goldberg was a contemporary of Bateman’s who worked primarily in American newspaper comics. From about 1909 to 1929, Goldberg was perhaps the foremost humor cartoonist in America. This 1916 magazine cover proclaims that Goldberg was “the world’s most famous newspaper cartoonist.”

Goldberg devised a vast amount of comics that pushed the limits in several different ways, most of which have never been reprinted since their appearances about 100 years ago and which are mostly unknown to modern audiences. Here’s one from 1915 that doesn’t look anything like what we think of as a comic, but it works (it was an April Fool’s Day joke):

Goldberg created a new comic, with new concepts every day. He was sort of a one man Saturday Night Live in comics. Here are six comics from a week in 1917. You can see how he varied his layouts, content, characters, and approaches.

When you hear “Rube Goldberg,” you probably think of a complicated machine used to accomplish a trivial task. Goldberg is famous today, to the exclusion of practically everything else he did, for one innovation in particular: his invention cartoon. Among its many virtues (including a sardonic running commentary on the dangers of blindly embracing technology), this format asks the question: do comics need multiple pictures to be sequential?

Here’s Goldberg’s “Self-Operating Napkin,” which was part of The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts, A.K. series that ran not in a newspaper but in Collier’s Weekly. The comic strip’s lead character, the mad inventor named Professor Butts, was never shown in the series – a formal trick worthy of Samuel Beckett.

As you work your way through steps A through M in this comic, you are about as sequential as it’s possible to get. One thing cannot happen until the thing before it happens. The sky-rocket (K), for example, cannot take off until the automatic cigar lighter (J) has been lit. Goldberg, who held a degree in engineering, knew that, as far as sequence in sequential narrative goes, there’s more than one way to skin a cat – as long as you have enough ropes, pulleys, assorted spaniels and fireworks.

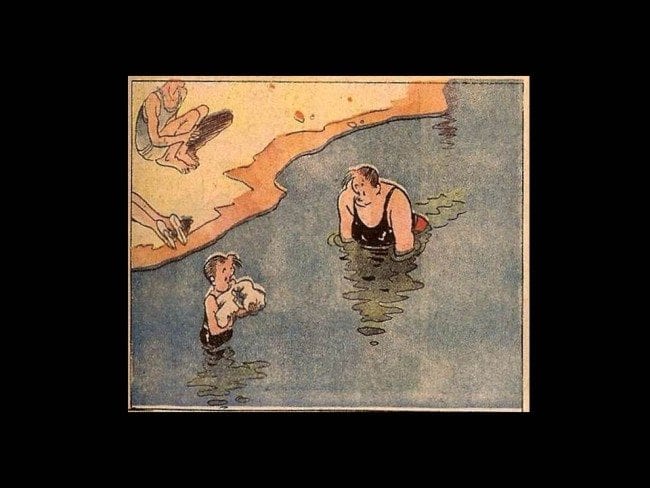

Frank King (1883-1969)

Another comics master who worked primarily in American newspaper comics was Frank King, who is best known for creating Gasoline Alley, still running in newspapers today. King drew this comic virtually every day from 1918 to 1959, and then it was taken over by other artists. Gasoline Alley offers gentle humor and drama centered mainly in a small American community. Within this framework of ordinariness, King performed some extraordinary tricks with formal elements.

Probably King’s greatest experiment was the unprecedented innovation of aging his characters so that they grew older in relation to “real” time. This could only work in a publishing medium that moves through time itself – such as a daily comic strip published for decades. The device made King’s characters more human and endearing for anyone who reads the strip (large chunks of which have been lovingly reprinted by Drawn and Quarterly in the Walt and Skeezix volumes designed and edited by Chris Ware and introduced and annotated by Jeet Heer).

The two main characters of interest are a heavy-set, automobile obsessed bachelor named Walt, and his adopted son Skeezix, who shows up on his doorstep one day in 1921. You can see by the panel from a 1945 example how the characters aged – Skeezix is now grown.

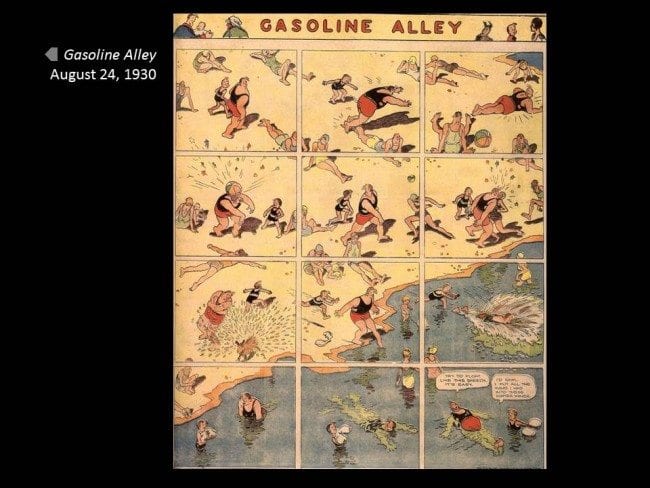

Gasoline Alley offers numerous intriguing visual experiments, particularly in the color Sunday pages. Here’s one that was original published on August 24, 1930, when Skeezix was nine. It’s a lovely summer day at the beach:

Walt and Skeezix are walking along in a well-delineated sequence of sight gags.

When we reach the water, we can feel the coolness of it in contrast to the warm sand. This is lovely impressionistic cartooning.

When we reach the water, we can feel the coolness of it in contrast to the warm sand. This is lovely impressionistic cartooning.

And then, in the very last panel, dialogue is spoken – typical of the tender exchanges between Walt and Skeezix.

And then, in the very last panel, dialogue is spoken – typical of the tender exchanges between Walt and Skeezix.

Now, this comic as shown panel-by-panel is perfectly satisfying and works one-hundred percent as a superb sequential graphic narrative (and this works especially when the page is presented in a series of projected PowerPoint slides, as it was in the original lecture). However, when you look at the entire pages as a whole, you realize that there is another layer present: a complete composition.

This page manages to be two things at the same time, like Kurtzman’s optical illusion cubes in his Hey Look! page. The presentation of the crowded public swimming beach in high summer as a composition is more than just a clever trick – it vividly establishes the sense of place, which connects us to Walt and Skeezix as they walk through it.

Gene Ahern (1895-1960)

Gene Ahern was a little like Frank King, in that his stuff looks quaint to a modern reader, but it contains a powerhouse of ideas and innovation when you take closer look. The nuttiness of Ahern’s screwball sense of humor exists in perfect tensegrity with his staid drawing style. Ahern’s comics are the equivalent of being goofy with a straight face. In 1936, Ahern started a comic strip called The Squirrel Cage which turns traditional narrative structure on its head.

Gene Ahern worked with organic continuities that stretched across years. His characters traded identities, dreamed inside of dreams, changed shape, and got lost in alternate realities, one of which was called “Foozland.” In this example, from December 15, 1946, take a look at how Ahern stretches the ligatures of connected narrative beyond the breaking point, pushing the American newspaper comic strip into dissonance and surrealism.

Our garden gnome hero (who years earlier was a super-strong giant of a man named Paul Bunyan) has eaten a plum that makes him dream while awake. He turns into a balloon, soars up into the clouds, is punctured by the sharp beak of a bird, and plummets to the earth. In the astonishing second tier, Ahern momentarily eschews words, showing us a series of abrupt location shifts in which each panel has a poetic dimension. In the last panel, in a circular logic similar to Bateman’s vacuum swallowing itself, or Kurtzman’s characters tearing up the page, we are told the only way to escape this dream is to go to sleep.

Perhaps the most enigmatic character in The Squirrel Cage is the Little Hitchhiker, a small man with a giant bushy white beard who perpetually asks the never-translated question: “Nov shmoz ka pop?” He always has an incongruous object by his side as he stands by a road and thumbs a ride. Other characters in the strip find the Little Hitchhiker annoying and unsuccessfully try to get rid of him with one crazy scheme after another.

Here’s an example from the strip’s fifth year of publication which may help explain the strip’s altered states of consciousness.

This is a primer on marijuana usage disguised as an ordinary newspaper comic strip. Robert Crumb, who famously imbibed consciousness-expanding drugs in the 1960s, has acknowledged that Ahern’s Little Hitchhiker was the model for his Mr. Natural. It’s incredible this comic, distributed by William Randolph Hearst’s King Features Syndicate, the largest comics syndicate in the world, was published in mainstream American newspapers. When you consider the date of publication, it helps to understand how this one slipped under the radar: December 7, 1941 – the day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in the United States.

Harvey Kurtzman (1924-1993)

Kurtzman’s work, perhaps more than that of any other American master of comics in the twentieth century, asks the question: can comics refer to themselves? Or, put another way, can the narrative in comics be about itself?

Kurtzman’s work (as observed by his artistic heir, Art Spiegelman) says, “Hey, let’s drop the pretense that this stuff is supposed to be real. Everything you consume for entertainment is lying to you: newspapers, books, ads, the movies, radio, TV, and even comics. And this is a comic!” His characters know they are drawings and they know what they are up to.

In the late 1940s, after World War Two, Kurtzman worked for Stan Lee at Marvel comics. He was given the creative freedom to write and draw funny one-pagers that were used as filler pages in comics like Nellie the Nurse and Tessie the Typist or any one of a dozen bland and interchangeable teen romance titles. Lee very likely didn’t care much what was done for the fillers, which were unimportant in his view.

Today, it is startling to flip through the dull hack stories in an issue of Mitzi, or Teen and find one of these brilliant pages, like a diamond in the desert. Kurtzman created about 150 Hey Look! pages, nearly all of which played in increasingly clever and adept ways with formal elements. Here’s one from 1948 in which we get the mind-blowing images of cartoon characters recreating themselves – the ultimate self-improvement comic:

I love that last panel because it shows how artists who push the limits reach into the void for something new. Kurtzman went on to create Mad, which pushed the limits so much that it is now an icon of 20th century culture. He worked with Bill Elder, a gifted screwball artist who could mimic the styles of other cartoonists so well that their lampoons looked at first glance like the real thing. Here’s Kurtzman and Elder’s parody of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley.

In one memorable sequence, they made fun of how the characters in Gasoline Alley age. Here, Skeezix wills himself to grow up over the course of four panels so that he is old enough to date a pretty girl!

Art Spiegelman (b.1948)

Kurtzman’s work influenced the generations of comic artists that came after. Perhaps the most famous of these is Art Spiegelman, author of the Pulitzer-Prize winning Maus which, when it was published, pushed the limits of the accepted definition of “comic book” and laid the groundwork for today’s bumper crop of long-form comics that marketers like to call “graphic novels.” Today, Maus stands as one of the most innovative, complex works in comics.

Long before Maus, Spiegelman was experimenting with comics. In the 1970s, along with Bill Griffith (Zippy), he edited a groundbreaking comics anthology called Arcade. In Arcade, Spiegelman contributed short-form comics that twisted the form like never before. Here’s a one-pager that asks the question: Can one comic have multiple stories/sequences?

This one-page comic (which has a typical Spiegelman-style pun in the title itself, taking off on the clichéd “A Day at the Circus” title) has six sequences. As with King’s beach strip, the strip offers something more than just a demonstration of artistic cleverness, since it addresses the vicious cycle that involves depression and alcoholism – a deadly circuit that’s certainly no circus. The page contains within it little sub-jokes that connect to the theme, such as one character telling the other not to talk in circles, or a “no U-turns” street sign.

This type of narrative that folds in on itself is a vital – if less obvious – part of Spiegelman’s Maus. He combines many narratives into one in the book, including his father’s stories in different times of his life, and Art Spiegelman’s own story about making the book!

Spiegelman’s Arcade limits-pushers are collected into a book called Breakdowns (again a pun in the title, which refers to both comics, psychology, and also the very act of pushing the limits this essay discusses).

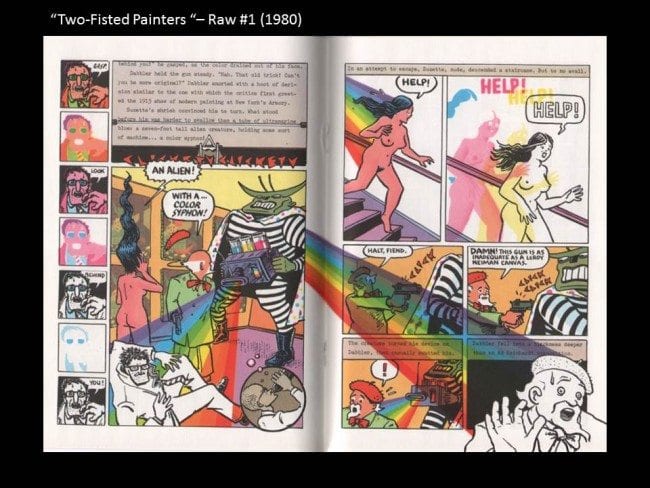

After Arcade, Spiegelman went on to publish Raw with Françoise Mouly, an ambitious anthology title that experimented with format as well as content (the sound of Ronald Regan repeatedly rasping out “can of poisoned meat” haunts my dreams, thanks to the flexi-disc record that was included in Raw #4). In the first issue of the oversized magazine, a small comic book by Spiegelman was inserted. It was called Tales of Two-Fisted Painters, and serves as another example of Spiegelman playing with formal elements. This time, it’s color.

Richard McGuire (b. 1957)

Spiegelman and Mouly’s Raw provided support to many other artists who have since gone on to expand the possibilities of comics as an art form. For example, Chris Ware was first published in Raw with “I Guess.” In 2014, Ware published Building Stories, which exploded the idea of a graphic novel, offering a box full of comics in various formats: pamphlets, newspapers, books, and even a game board. Incredibly, Building Stories (the title contains a double meaning, by the way, à la Spiegelman) truly is a novel in that a complete narrative emerges, no matter in which order the pieces are read.

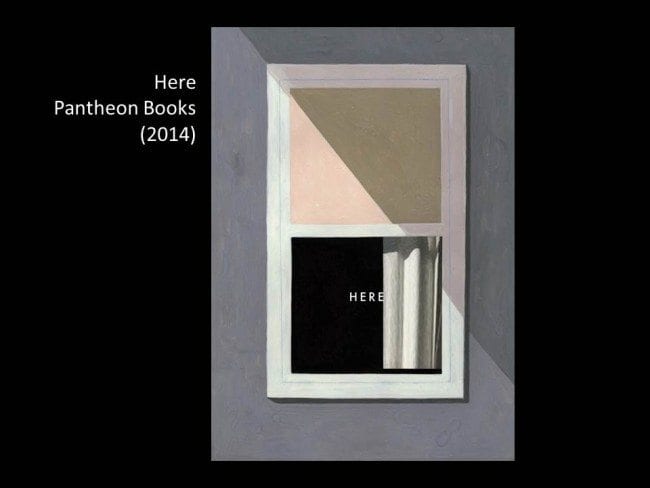

Another singular limits pusher to emerge from the pages of Raw is Richard McGuire. His six –page 1989 comic entitled simply “Here” asks the question: Do comics have to be sequential?

We begin with an enigmatic blank panel -- merely a few lines to indicate the corner of a room inside of a house.

Next, a familiar narrative sequence, using small jumps in time.

We see a woman pregnant with child, telling us that “it’s time” (another double-meaning, since the comic is going to play with time like no other comic before or since). We stay with these characters for three and a half more panels, making little jumps forward in time that are just far enough apart to keep us from settling in and comfortably identifying with the “main” characters, who are drawn flat, like soulless clip art. Adding to the disorientation is the fact that the view of the room never alters. It’s as if we, the reader, are bound in place, looking through one of those spooky paintings in haunted houses where the painted eyes can be removed to allow a person to secretly scan the room.

In the fifth panel, there’s a panel within a panel, one time stamped 1922, and the other 1957, the time stream we started out in. The new mother asks for a bottle.  A poetic continuity occurs between the fifth and sixth panel, and between 1957 and 1971 as a new character brings a drink to an unknown speaker. Our woman in 1957 answers,“Thanks.” And in 1999 a cat leans against something – we can’t see what – that is in the same place as the leg of the 1971 woman.

A poetic continuity occurs between the fifth and sixth panel, and between 1957 and 1971 as a new character brings a drink to an unknown speaker. Our woman in 1957 answers,“Thanks.” And in 1999 a cat leans against something – we can’t see what – that is in the same place as the leg of the 1971 woman.

In just six panels, McGuire has managed to blow traditional ideas about depicting sequence into smithereens. It’s not just time, it’s space, too. “Here” forces us to consider how limiting panel borders are, and how – in comics, the outside edges are as fundamental a phenomenon as time itself. “Here” goes on with the same static viewpoint and characters conversing across time, and the layers of meaning accumulating, onion-like, for another mind-blowing five pages.

If one were to hold a camera in stillness over McGuire’s drawing board for about the last 35 years you could make a McGuire-like leap from the original 1989 black and white short to his thick, color book version, published in 2014. You could say that McGuire has jumped from “here” to Here.

In this lyrical spread from the 2014 version, a young plays piano in 1964 (McGuire is himself a musician) while three other girls from time periods dance in the same space, seemingly to her music. As with King’s beach Sunday of Gasoline Alley, Spiegelman’s A Day at the Circuits and Maus, McGuire’s Here blazes a path into new territory that reaches beyond the panel borders of our general understanding of what makes a comic. Hear, hear – or, better yet: here, here!

David Lasky (b. 1967)

David Lasky has collaborated with Frank M. Young on two books that reach back into America’s past: Oregon Trail: Road to Destiny (Sasquatch Books, 2011) and The Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song (Abrams ComicArts, 2012). Lasky and Young won an Eisner Award for the latter title. Not as well known, but just as entertaining and intriguing, are Lasky’s poetic and form-stretching comics. Mostly published in various anthologies and short run projects, these comics deserve a broader readership and it is hoped they may someday be collected into a widely distributed book.

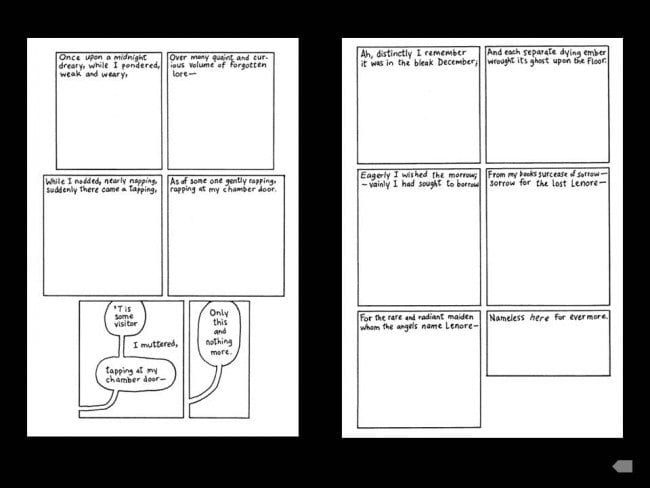

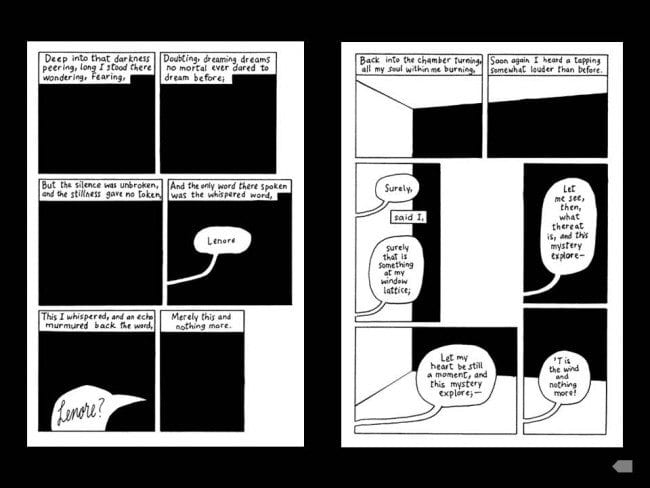

In 2002, Lasky published “The Raven” in Orchid, a collection of Victorian horror edited by Dylan Williams. Where a cartoonist like H.M. Bateman explored “silent” comics, Lasky’s "The Raven" asks the question: Do comics need to have pictures?

In Lasky’s own words: “Edgar Allan Poe was a longtime favorite writer of mine, but comics adaptations of his stories were most often disappointing, with artists drawing images much scarier and over-the-top than was necessary. Poe’s writing, after all, was scary enough by itself. So I decided to let the words do most of the work in my adaptation of his most famous poem. I made a rule for myself that I could use panels, word balloons, etc, but I could not draw any actual pictures. I also allowed myself the use of solid blacks, and abstract black shapes (feeling a bit influenced by the black and white paintings of Robert Motherwell)."

Lasky’s treatment smartly plays with positive and negative space, using solid blacks to suggest the raven's obsidian eyes, feathers, and beak as well as the elemental darkness/nothingness it symbolizes in Poe’s poem. An artist interested in visually expressing music in comics (something that led to a lovely innovation in The Carter Family: Don’t Forget This Song in which singing is represented by abstract visual forms), Lasky has devised panel structures to complement the structure of the poem, assigning a single page to each of the poem’s 18 stanzas.

In his one-pager, “Autobio Challenge,” Lasky deconstructs a popular modern form of comics. The work also prods at the essential nature of identity and form itself.

The page was a spontaneous creation, conceived and completed in a few hours one night in 2013 at DUNE, the monthly, open-to-all Seattle comics creation event devotedly run by Max Clotfelter. On the third Tuesday of every month about 50-75 people gather at the Café Racer in Seattle’s University District to create comics. The goal is to start and finish a one or two-page comic between 7 pm and 11 pm (when the last bus leaves). You hand Max your finished art and three bucks and the next time you come to DUNE, you get your art returned with a printed mini-comic containing all of the comics created in that single evening.

As DUNE demonstrates so well, comics as a form of authentic artistic creation and self-expression are more vital than ever. As the examples I’ve cited here, and so many others, show, comic art is not only a self-aware form, but it is also a form that continually redefines itself.

Who’s to say to what a comic is? It’s what you want it to be.

+++++++

This essay is based on a guest lecture I gave on August 5, 2015 at the University of Washington to a comics theory class, taught by Jose Alaniz, an Associate Professor at UW and author of Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond (University Press of Mississippi: 2014). All images used in this essay are copyrighted by their respective copyright holders.