The subject of this essay is the first six issues of Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows’ Providence, but let me begin with an apology. In Comics Journal #278 (October 2006), I wrote a negative review of Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s Lost Girls, arguing that Moore’s rigidly schematic plot made the book a chore to read, despite the beauty of Gebbie’s art. I still think Lost Girls is minor Moore, but I went too far in the final paragraph of my review. In response to Moore’s claims that he was retiring from comics (most fully expressed in an interview in Comic Book Artist #25 [April 2003]), I wrote that he was “leaving comics none too soon and many years too late” (138). I was disappointed with much of the America’s Best Comics line (though for me Promethea was major Moore), but I regret those words. They show ingratitude to a writer who entertained me for decades while inspiring other creators to produce better comics.

I was also wrong about the decline of Moore’s career. The next big book after Lost Girls was The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Black Dossier (2007), drawn by Kevin O’Neill, and at the time I was so disillusioned with Moore that I ignored Dossier. Last spring, however, while preparing to teach a seminar on Moore’s career (and on related topics like fan fiction, postmodernism, Anonymous, film adaptation, etc.), I finally read Dossier and loved much about it, especially its inclusion of such beautiful embedded texts as a 1984-inspired Tijuana bible, a lost Shakespeare play, and a 3-D trip (with glasses) to the Blazing World. (As Marc Singer points out, Dossier is “a beautifully designed book,” a triumph of graphic design.) Judging from the Amazon ratings, however, most readers were less enthusiastic for Dossier’s mad heteroglossia. Representative is a comment from “L. Dawson,” who wrote, “Moore suffers under the weight of his own genius with extremely obscure literary references taking [the] place of compelling storytelling. Very, very hard to get through the dossier portion of this book. No fun.” Clearly Dawson and I have different definitions of “fun.”

Not that Dossier is flawless. Singer zeroes in on the book’s conclusion—as Mina Murray and Alan Quatermain flee into the Blazing World to escape from James Bond and other members of the British espionage fraternity—as dramatically unsatisfying. For Singer, the Blazing World is too much a repetition of “the Immateria, or Ideaspace, or whatever else Moore has called this realm where all fictional creations rub elbows and share equal ontological footing.” Singer further claims that the flight into a dreamy Utopia represents a troubling abrogation of heroism. Once Mina and Alan arrive in Fantasyland, they abandon those still suffering back on Earth: “The end of The Black Dossier is not just a retreat from the world, it’s a retreat from any sort of ethical responsibility to the world.” It’s also a narrative cheat, a deus ex machina unmotivated by earlier story events. For this essay, however, it sets up a fascinating context: in later Lovecraft-infused comics like Neonomicon and Providence, Moore contrasts the idealism of the Immateria / Ideaspace / Blazing World with Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, a dialectic I’ll discuss later.

The biggest problem with the final pages of Dossier, however, is the Golliwog, the English Sambo-figure who pilots Mina and Alan to the Blazing World. Moore claims that his Golliwog returns the character to its original, non-racist version, but Pam Noles has convincingly argued that even the first representation of the Golliwog (in writer Bertha Upton and illustrator Florence K. Upton’s book The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg” [1895]) sprang out of a culture of blackface and minstrelsy, and drags those connections to racist culture into the Dossier. Moore knows this: he makes jokes about it. When Mina Murray asks the two dolls why they travel with the Gollywog, one doll replies, in Dutch, “His masculine organ of reproduction is enormous.” (Thanks to Jess Nevins for the translation.) Perhaps Moore’s Golliwog is like Robert Crumb’s Angelfood McSpade: a character that can be read simultaneously as an authorial admission of racism (think of how, in interview after interview, Crumb owns his prejudices), as a confrontational exploration of the enduring power of racist images in Western culture, and as an exaggerated send-up of those racists dumb enough to believe in and fear a wretched stereotype.

Another ideological problem: as many critics point out, most of Moore’s comics include a rape scene—usually man-on-woman, though occasionally man-on-man, like the schoolboy who rapes Johnny Bates in Miracleman #14 (1988)—and Dossier is no exception, although I'm not comfortable moving from these scenes to an ad hominem claim that Moore himself is sexist and somehow turned on by rape. In Watchmen (1986), I’m troubled by the Comedian’s assault of Silk Spectre because she falls in love with her sexual abuser, but Jimmy Bond’s attempted rape in Dossier ends with Mina beating him senseless with a brick hidden in her purse. In Dossier, Mina outsmarts Bond, which isn’t hard, but Moore makes her smarter and more courageous than Quatermain too.

For me, the issue of rape in Moore’s comics is similar to what feminist film scholar Tania Modleski says about violence against women in the films of Alfred Hitchcock. According to Modleski, Hitchcock’s stance towards women is ambivalent: scenes like the rape and strangulation in Frenzy (1972) make the case for a prima facie misogyny, but Hitchcock’s movies also showcase female characters whom we identify with as they suffer, a connection that reveals to the viewer the intolerably subordinate place of women in male-dominated societies. As Modleski writes:

It has long been noted that the director is obsessed with exploring the psyches of tormented and victimized women. While most critics attribute this interest to a sadistic delight in seeing his leading ladies suffer, and while even I am willing to concede this point, I would nevertheless insist that the obsession often takes the form of a particularly lucid exposé of the predicaments and contradictions of women’s existence under patriarchy. (The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory, 2015 edition, 25)

This quote is from Modleski’s close reading of Blackmail (1930), a film where Alice, a woman who kills a would-be rapist, is confronted by a thug and blackmailer who threatens to reveal her crime to the police. Hitchcock positions Alice in a limbo between the letter of the Law and her understandable desire to protect herself, a double-bind that spectators, including male spectators, find painful and unfair. The ways Hitchcock presents physical and psychic violence allows us to experience the violence from the female point of view, which leads to a better understanding of how patriarchy mistreats women.

Do the rapes in Moore’s comics express an ambivalence similar to Hitchcock’s? It’s difficult to say, because Moore often changes his approach to sex and violence (and sexual violence) across the relatively short span of a single book, much less his entire career. The attempted rape of Evey that opens V for Vendetta (1989) clearly aligns us with her character—she is an innocent forced by a cruel dystopian government to prostitution even before she is attacked by corrupt cops—but the mind-fuck epiphany she undergoes later in the book is more complicated. Evey is subjected to humiliation and sexual abuse administrated by V to improve her, to convince her of the truth of V’s philosophy, a process which Isaac Butler sees as raping Evey’s character “into enlightenment. Stockholm Syndrome is liberty. Also, War is Peace and Ignorance is Strength. Just shut your pretty little mouth and do what the author tells you.” (You should read Butler’s V for Vendetta essay, posted on The Hooded Utilitarian, along with its 178 [!] comments, some defending Moore.) There is no easy way to generalize about the sexual violence in Moore’s stories. We need to look at the narrative context for each instance of rape.

Recent discussions of Moore seem dominated by two topics: his refusal to play ball as DC Comics greenlights prequels to Watchmen and blockbuster movies based on his comics, and by readers’ dismay over troubling aspects of his recent work. I think, though, that I'd like to hear more about him as a creator. Singer writes that “for the first hundred and sixty pages or so, The Black Dossier looks like it will indeed live up to Moore’s promise that it would be ‘the best thing ever.’” Then the Golliwog shows up and poisons the punch, but the Golliwog and the weak ending are only 15 percent of the book. Thousands of words—too many of them by Moore himself, in his ill-advised, supremely defensive Christmas 2013 letter—have been written about the Golliwog, but not enough about the aesthetics of his writing, about what makes most of Dossier “the best thing ever.” We have to talk about race and rape when we discuss Providence, but I’ll also talk about Moore as a writer rather than an ideological symptom.

From this point on, then, I’m going to spoil the hell out of Moore and Burrows’ The Courtyard, Neonomicon, and Providence. I’m also going to ignore other Moore comics that include Lovecraft elements, such as the recent League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Janni Nemo spinoffs—partially for brevity’s sake, and partially because these books aren’t the deep, critical dive into Lovecraftiana that Providence is.

Two other notes. Several of my ideas were first discussed (and refined) in the Moore seminar mentioned earlier, so I'd like to thank the students in that class--Dean Cates, Wade Morgan, Ryan Morris, Vito Petruzzelli, Morgan Pruitt, Kevin Pyon, Logan Scott, Matthew Staton, Justin Weltz, and Jessica White--for their insights and enthusiasm. Also, I'm an avid reader of a superb blog, Facts in the Case of Alan Moore's Providence, and much originally presented in Facts has snuck into my thinking about Providence. You'd be best off reading Providence first, then the Facts blog, and then the following essay.

Alfred Hitchcock: "A glimpse into the world proves that horror is nothing but reality."

After completing Dossier in 2007, Moore turned to three major projects: Jerusalem, a million-word prose novel to be published in spring 2016, more League of Extraordinary Gentlemen books, and Neonomicon (2010) and Providence (2015- ), two comic-book contributions to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. Moore’s interest in Lovecraft, however, predates the mid-2000s. In 1994, Moore wrote “The Courtyard,” a Mythos prose short story published in the anthology A Starry Wisdom: A Tribute to H.P. Lovecraft (1995). A two-issue comics adaptation of “The Courtyard” followed in 2003 from Avatar Press.

The comic-book Courtyard, with art by Jacen Burrows and “sequential adaptation” by Antony Johnston, is available in Avatar’s collection of Moore and Burrows’ Neonomicon. It’s the tale of homophobic, racist F.B.I. agent Aldo Sax, whose investigation into serial killings leads him into a Lovecraft-themed Brooklyn underground. Sax tracks down what he thinks is a new street drug, Aklo—and discovers from enigmatic pusher Johnny Carcosa that Aklo is instead an ancient language, an “ur-syntax,” the “primal vocabulary giving form to those pre-conscious orderings wrung from a hot incoherence of stars, from our birthmuds pooled in the grandmother lagoon: a stark limited palette of earliest notions. Lost colours. Forgotten intensities.” (As Sax trips on Aklo and muses on the “hot incoherence of stars,” the image of a giant, tentacled eyeball surrounded by stalagmite teeth takes up three-fourths of a double-page splash.) The Courtyard ends with Sax driven mad by Aklo, and becoming a murderer himself:

Many of the stylistic traits established in the Courtyard adaptation carry over into Moore’s later Lovecraftian comics: uniform panel grids (in Courtyard’s case, two long vertical panels per page), compulsive, incessant allusions to Lovecraft and his circle (Sax visits “Club Zothique,” named after a group of short stories by Clark Ashton Smith), and a story set in a parallel world similar, but not the same, as our own. (The story’s opening refers to a fictional holiday, “Farrakhan Day,” and to “the Harlem Dome,” a giant protective shield; in Neonomicon, we discover the existence of city-spanning domes, and Providence explains why they were originally built.) The Courtyard also revisits topics and themes common in Moore: Aklo is another instance, however dark and creepy, of Moore’s belief in the ability of language to shape perception and consciousness.

Despite links like these to Moore's preoccupations, I find The Courtyard disappointing. Burrows improves as an artist, especially between Neonomicon and Providence, but in the earlier Courtyard his bodies are oddly elongated, his faces are inexpressive, and his depiction of Sax’s Aklo-fueled visions aren’t as disturbing as they need to be. Antony Johnston’s “sequential adaptation” is faithful to Moore’s prose, but in both versions of the story, Moore’s fusion of Lovecraft references and a punk/goth counter-culture comes off as corny and forced. In an episode of the podcast Comic Books are Burning in Hell on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century (2009-2012), Matt Seneca comments that when Moore’s characters burst into song (think of V’s “vicious cabaret,” or “Song of the Terraces” [1990], the musical episode of The Bojeffries Saga), the results are “the worst ever,” and that Moore’s depiction of contemporary underground music in Century’s third chapter is wholly inauthentic. The situation’s no better in The Courtyard, where Randolph Carter and the Ulthar Cats sing “Zann Variations”—which includes the lyrics “Where a smoke-river, factory black, crawls below the stone bridges, old violins play / And the crippled dogs whine in their sleep all along Rue d’Auseil.” (I do like Moore's "Miskasonic" pun, though.) I didn’t read the two issues of The Courtyard when they were originally published, but if I had, I probably would’ve stuffed them in a file drawer with other unsorted comics and forgotten about them. I would not have predicted that Moore would get very serious about writing in the Cthulhu Mythos, although from Miracleman to Swamp Thing to the Charlton Action Heroes to Superman, the spine of Moore’s career is his skill at extracting art from fictional characters and worlds created by someone else.

Alfred Hitchcock: "Blondes make the best victims. They're like virgin snow that shows up the bloody footprints."

Moore and Burrows’ Neonomicon (2010) is a sequel that takes place a few years after the events of The Courtyard, as two new characters, F.B.I. agents Merrill Brears and Gordon Lamper, visit a high-security insane asylum to speak to prisoner Aldo Sax. (This scene is a high-key variation on the meetings between Hannibal Lecter and Clarice Starling in the Silence of the Lambs film [1991].) After committing murder at the conclusion of The Courtyard, Sax took more lives before he was caught; he decapitated all his victims, cut off their hands, and carved their torsos into flower-like shapes, a technique now emulated by a copycat killer. Sax refuses to help Brears and Lamper—he speaks in unintelligible Aklo for most of their visit, until a mention of Club Zothique makes him quiet and sullen—so the F.B.I. raids the Club (and, subsequently, Johnny Carcosa’s apartment) to bring the Lovecraftian underground to light.

Carcosa escapes, but one clue emerges from the raid: Carcosa ordered “weird starfish dildos and shit” from Whispers in Darkness, a New Age supply store in Salem, Massachusetts. In disguise, Brears and Lamper visit the shop, and chat with owner Leonard Beeks, who ushers the agents into a room of Cthulhu sex paraphernalia and invites them to a get-together “for genuine devotees” later that night. The party turns out to be a descent into a sub-basement with Beeks, his wife, and a handful of followers, leading to an orgy in a brackish pool, where Lamper is killed and Brears is raped by Beeks’ gang. (In its juxtaposition of hidden underground secrets and blunt violence, Neonomicon’s pool scene reminds me of the second half of Pascal Laugier’s torture porn film Martyrs [2008].) Then a fish-man, one of the Deep Ones from Lovecraft’s story “The Shadow over Innsmouth” (1931), swims into the pool, and throughout most of Neonomicon #3 repeatedly rapes Brears, except for the time she jerks off the creature instead.

If this isn’t offensive enough, Moore defines his characters in ways that allow him to both critique and wallow in Lovecraft’s prejudices. Lovecraft was racist, anti-Semitic, homophobic: as a young man, he wrote a poem titled “On the Creation of Niggers” (1912), which is as horrible as it sounds, and Lovecraft’s estranged wife claimed that his virulent anti-Semitism destroyed their relationship. (In November 2015, the World Fantasy Awards dropped the look of their trophy, a Gahan Wilson-designed bust of Lovecraft, over increasing complaints about Lovecraft’s xenophobia.) As Moore himself writes in his introduction to The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft (2014): “Far from outlandish eccentricities, the fears that generated Lovecraft’s stories and opinions were precisely those of the white, middle-class, heterosexual, Protestant-descended males who were most threatened by the shifting power relationships and values of the modern world” (xiii). Lovecraft expressed his prejudices most directly, however, in the nearly one hundred thousand letters he wrote to friends and fellow writers; in his published fiction, it’s mostly hints and metaphors, as in the miscegenation terrors of “The Shadow over Innsmouth” and the latent homophobia / homoeroticism of “Herbert West: Reanimator” (1922), which Noah Berlatsky traces in his review of a volume of earlier comics adaptations of Lovecraft.

In an early promotional interview about Neonomicon, Moore described his method as bringing all of Lovecraft’s repressed “stuff”—“the racism, the anti-Semitism, the sexism, the sexual phobias which are kind of apparent in all of Lovecraft’s slimy phallic or vaginal monsters”—up to the surface of the text. Just as troubling, however, is how Moore positions his characters in these Lovecraftian pathologies. Gordon Lamper is African-American, so when Brears and Lamper descend into the sub-basement, Beeks and his group toss off racist comments like “Do you know you’re our first Black boy?” and “Show us some of that Black power.” After Mrs. Beeks shoots Lamper in the forehead, the racist epithets intensify as the cultists carry Lamper’s body out of the pool area and half-bury it in a mud room. (In Neonomicon #4, F.B.I. agents raiding the basement find Lamper’s rotting corpse.) The Lovecraftian elements of Neonomicon are unsettling, but I find the casual, tossed-off death of Lamper even more disturbing, perhaps because it reminds me of the 1964 chain-whipping, murder, and burial of James Chaney.

Lamper is a non-complicit victim in the atrocities of Neonomicon, but what about Brears? On the third page of Neonomicon #1, as she and Lamper arrive at the asylum to see Aldo Sax, Brears refers to her “breakdown,” and subsequent dialogue clarifies that she just returned to the F.B.I. after medical leave and therapy for sex-addiction, alcoholism, and low self-esteem. In a later scene in the first issue, Brears and Lamper’s boss, the considerably older Carl Perlman, takes Brears aside and tells her, “You ever want to go back to how things were, you let me know, huh?” Clearly Perlman, Brears’ boss, had sex with her when she was ill and vulnerable, and here he volunteers to continue his exploitation the minute she’s out of the hospital. (This is another similarity that Neonomicon has to The Silence of the Lambs, where Clarice Starling is surrounded by alpha male F.B.I. agents who display sexism is ways only slightly less obvious than Perlman’s lechery.) Perlman’s behavior is Moore’s way of letting us know that the fish-man isn’t the only rapist in Neonomicon. After Perlman’s offer to return to “how things were,” we see Brears standing isolated from the male agents, a sad, pained look on her face:

Brears’ slumped shoulders and slightly bowed head (nicely captured by Burrows) convey defeat. She knows she’s returned to a job where she will be defined by her sex addiction, by the men who took advantage of her or wish they’d done so. Brears’ situation is “a particularly lucid exposé of the predicaments and contradictions of women’s existence under patriarchy,” and our sympathies lie with the vulnerable woman trapped in the torturous environment.

When Brears’ situation becomes even more horrible in the Beeks’ torture pool, Moore makes provocative creative choices when representing her victimization. As she is raped, Brears passes out, but even her dreams have been colonized: she envisions herself naked in a Lovecraftian city, as Johnny Carcosa strolls into her subconscious, speaks with her, and kisses her. In a curiously affectless tone, Brears seems to eroticize the rape as she describes her plight to Carcosa:

One aspect of The Courtyard and Neonomicon that annoys me is Carcosa’s lisp, created by the thin membrane of flesh across his mouth. During their conversation, he notes that he and Brears are dreaming of the sunken city of R’lyeh (“Thith ith R’lyeh. R’lyeh ith in you”), where the cosmic entity Cthulhu is imprisoned, and he also calls Brears “a nun, thee, athian merry,” a phrase she eventually realizes is “Annunciation Mary.” The kicker of Neonomicon is that the fish-man impregnates Brears with Cthulhu. She is the not-so-virginal Mary of a new Dark Age that will wipe humanity off the earth. In keeping with Moore’s desire to expose the sexual connotations of Lovecraft’s images, R’lyeh, the city at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, is a metaphor for Brears’ womb.

How does Brears feel about being the apocalyptic “Annunciation Mary”? In the last chapter of Neonomicon, Brears explains her experiences to Aldo Sax, the one person “who might understand,” and reveals that she is pregnant with Cthulhu. Then this page, the second-to-last page of the story:

“Although, y’know, I imagine my mind’s being influenced”: Brears has been mentally, as well as physically, raped. (I’m old enough to remember how Marcus used the “subtle manipulation” of brainwashing machines to rape Ms. Marvel in Avengers #200 [October 1980].) Brears’ personality undergoes a wrenching shift. Previously, she was a law enforcement agent, but she now considers our entire species “vermin” and our civilization “bullshit,” even as her self-esteem problems are cured. As Annunciation Mary, she is reduced to nothing more than a vessel for Cthulhu. Sax calls her a “goddess,” but that kind of worship is just another refusal to treat her as an autonomous person, another form of rape. (I’m reminded of a gag from one of Steve Martin’s early Saturday Night Live appearances: “I believe you should put a woman on a pedestal…high enough so you can look up her dress.”) Brears is both Annunciation Mary and a "dirty fucking whore," a piece of meat to be indiscriminately fucked and brainwashed: she is trapped in a monstrous literalization of the Madonna/whore complex. Even if we stripped the narrative of supernatural elements like the fish-man and Cthulhu, Brears would still be victimized by the all-too-mortal misogyny of Perlman and the Beeks, and that is the true horror of Neonomicon.

Alfred Hitchcock: "I'm a writer and, therefore, automatically a suspicious character."

And so we arrive at Providence, which is, at least so far, a prequel to The Courtyard and Neonomicon, set in the same fictional world. There are numerous connections between all three works. The domed cities of The Courtyard and Neonomicon, for instance, are explained in Providence as a defense against dangerous meteorites, following an 1882 crash in Manchester, New Hampshire that brought a pestilence to the land. Moore and Burrows’ meteorite is borrowed directly from Lovecraft’s short story “The Colour Out of Space” (1927), and in Providence Moore assembles the major Lovecraft characters, locales, and plots into a single coherent narrative. By re-envisioning both Lovecraft and his own earlier contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos, Moore creates a network of allusions that supports all the events of Providence’s plot. It’s possible to read and understand Providence without a familiarity with Lovecraft, The Courtyard, and Neonomicon, but I wouldn’t want to.

Providence is set in 1919, immediately after World War I (or what a group of fish-human hybrids calls “the Great Dry Cull”), and tells the story of Robert Black, a reporter for the New York Herald who is galvanized by an encounter with a scientist named Dr. Alvarez. In Providence #1, Black and Alvarez have a long talk about, in Black’s words, “a buried or concealed America composed of everybody’s secret lives. I could imagine a whole hidden world of individuals trading occult or exotic science lore and information, a society of characters as striking as Alvarez that conducts itself unseen below the daily fabric of America.” Hints of this occult underworld inspire Black to resign from the Herald, and travel to Massachusetts and New Hampshire to conduct research about this “hidden world” for a book (Marblehead: An American Undertow) he wants to write. The first four issues of Providence feature Black interviewing eccentric characters associated with the occult underground—Alvarez, book seller Robert Suydam (#2), trader Tobit Boggs (#3), and Garland Wheatley and his reclusive family (#4)—but Black is skeptical of the power of this underground until, in Providence #5-6, he is victimized by indisputably uncanny mystical forces.

Black is no stranger to secrets. In early 20th-century New York, he is Jewish and gay, and hides both from many of the people in his life, such as his co-workers at the Herald. (He is, however, well connected to the New York gay underground, and actively pursues liaisons with men of a “kindred spirit” during his research trip.) Moore has noted that he’d made Black gay and Jewish to explore what it means to be an “outsider,” but not in a way that emphasizes Black’s involvement with some sort of proto-identity politics. Rather, Black is a meta-commentary on Lovecraft’s own personal (and perhaps unwarranted) sense of alienation. As Moore points out, Lovecraft “saw himself as a stranger in the 20th century, as an outsider,” but he also shared, and expressed in virulent terms, the anti-Semitic and anti-African prejudices of dominant WASP society. Moore again: “In Providence, we kind of examine the idea of the outsider. Who is the real outsider? Is it Robert Black? Is it any of the characters we meet during the course of Providence where their outsider status might perhaps be more profound? Providence gives us a chance to look at that and Robert Black seemed like an interesting character for it.” Like Lovecraft, Black is much less of an outsider, and much more of a mouthpiece for "normal" society, than he thinks he is.

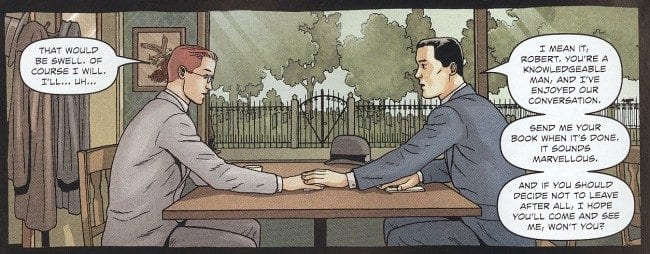

Because he has this inflated sense of himself as an “outsider,” even while he espouses and practices the same conservatism as Lovecraft, Black is often unsympathetic and unlikable. In Providence #1, Black has fallen in love with Jonathan “Lillian” Russell, an effeminate member of the Manhattan gay demimonde, but ends their affair when he discovers that Lillian is an acquaintance of his New York Herald employer and editor. A flashback portrays the moment when Black abandons Lillian:

This panel is clever, since Providence #1 riffs on the Lovecraft story “Cool Air” (1928)—about a scientist who prolongs his life by living in a chilled apartment—even while Lillian realizes Black is emotionally “cold.” (Ironically, Moore’s scientist, Dr. Alvarez, is a frozen zombie who has a more loving relationship with his landlady than the biologically-alive Black can sustain with Lillian.) For Black, his hypocritical façade of normalcy is more important than the man he loves.

Black’s hypocrisy and cowardice are emphasized by the passages we read from his personal diary. Moore and Burrows include excerpts from prose texts in the final pages of each issue of Providence—just as Moore and Gibbons do at the end of each chapter of Watchmen—and almost all of these appendices are from Black’s “Commonplace Book,” a diary of his travels and research. These Commonplace Book passages combine with Providence’s dominant story to illuminate Black’s personality and states of mind, and not usually to his credit. At the conclusion of the words-and-pictures section of Providence #1, for instance, Black discovers that Lillian, driven by heartbreak, has committed suicide, and the prose diary excerpt that follows is mournful: Black begins by writing that he’ll never “stroke that hair” and “cup that chin” again, and ends with “My Lily’s dead, because I am a coward and because I keep pretending. I’m not any kind of writer.” Black then scratches out these words, and spends the rest of Providence’s six issues running away from his guilt and pain over Lillian’s death. In subsequent diary passages, Lillian is barely mentioned, as Black chronicles in detail his short-lived crushes and affairs with men he meets during his travels: detective Tom Malone, an Irish laborer named Brendan he picks up around Times Square, and an unnamed “flame” he meets in Athol, Massachusetts.

Tom Malone comes off best in Black’s diary—perhaps because they spend very little time together and never consummate their attraction—but Black is snobby and judgmental about his actual lovers. He describes Brendan as a “bore” who ruined their encounter by “opening his mouth,” and speculates that “if an uncommon thought or word had ever resonated in that vaguely ox-like skull it would have thrown him into seizure.” The Athol flame is derided for his “ridiculous and vacuous attempts at conversation.” Similar rhetoric is used to describe other people in Black’s life, particularly his New York Herald co-workers. His editor Ephraim Posey is a pompous martinet (“Our Lords & Masters”), his fellow reporter Freddy Dix is “hopeless,” and secretary Prissy Turner commits the sin of her own crush on Black: she is described as “making googy eyes” at him, before she “started squeaking in her usual empty-headed fashion.” Later, in the mid-August diary excerpts in the back of Providence #4, Black refers to Prissy as a “scatterbrain,” yet still compares her “favorably” to his Athol lover: “Beside my current very temporary romantic interest, Prissy is Sir Isaac Newton.” Then Black schemes to check out of his hotel and continue his research trip without saying goodbye to his “temporary romantic interest.” The Robert Black in the comic-book Providence story is cultured, mild-mannered, and unfailingly polite, but the diaries show that he’s secretly a gossipy jerk, a character in desperate need of a comeuppance.

Alfred Hitchcock: "I have a feeling that inside you somewhere, there's somebody nobody knows about."

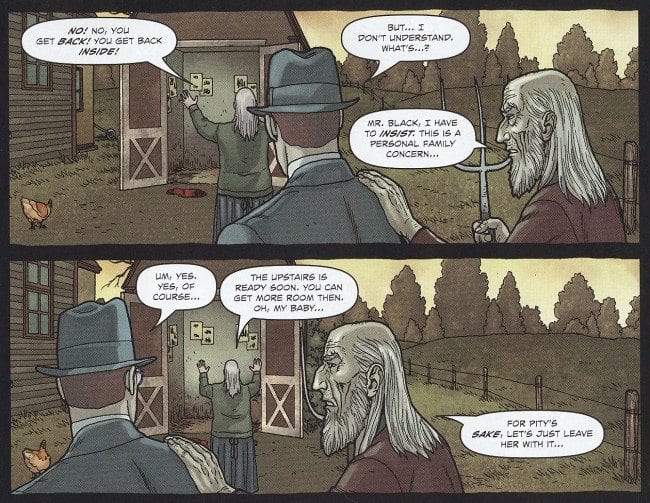

Even as Black hides his true feelings (and disdainful judgments) from his lovers and interview subjects, Moore’s plot leaves Black ignorant of the power of the occult societies he investigates. Black is the center of our attention—most of the story information is filtered through his encounters and perceptions—but flashbacks and contemporary scenes unmoored (pun intended) from Black’s perspective give us a fuller picture of Moore’s Lovecraftian conspiracies. The first two panels of Providence #4, for instance, are blurry and unreadable:

Later in the story, Moore replays this scene, revealing through narrative context that the earlier images are from the point-of-view of an invisible, misshapen offspring of the Wheatley family:

The tragic secret at the center of Providence #4 is that renegade magician Garland Wheatley has impregnated his own daughter in an attempt to create a prophesized herald for the Cthulhu world to come. A flashback depicts Garland Wheatley mounting his daughter Leticia, and the result is John-Divine, a creature whose existence remains hidden to Black. One irony is that Providence #4 (and specifically the observations of another uncanny Wheatley sibling, Willard) make it clear that Black is some kind of harbinger of the dark era, but Black misunderstands: he thinks that every time someone calls him “herald” or “herald-man,” they’re only referring to his previous job as a reporter at the New York Herald. Like so much of Providence, this dual discourse originates with Lovecraft. In an introduction to an anthology of the canonical Cthulhu stories, Robert Bloch credits Lovecraft with the ability to create intelligent, credible narrators whose monologues nevertheless reveal “to the reader more than the narrator himself is aware of” (The Best of H.P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre, 1987, xxi). Across the first six issues of Providence, as Black interviews what he considers an eccentric, harmless group of would-be magicians and occult scholars, we increasingly understand the depths of the monsters and secrets he’s stirring up.

The cause of the cosmic horror in Providence is an elaborate occult history, heavily borrowed from Lovecraft, which Moore reveals to the reader through fragmentary clues. As hinted at in Providence’s main comic-book narrative, and more fully and directly described in the prose appendices, the “buried or concealed America” that Black investigates is based on the Kitab Al-Hikman Al-Najmiyya (Moore’s cognate for Lovecraft’s Necronomicon), a book of forbidden knowledge written by Khalid ibn Yazid in 703 A.D. The Kitab is revised five centuries later by an alchemist named Ahmad ibn Ali ibn Yusuf Al-Buni, and then translated into Latin and English in the 16th and 17th centuries. The English version of the Kitab is Hali’s Book of The Wisdom of The Stars, and one of the hallucinogenic climaxes of Providence #6 is Black’s first experience reading Hali’s Book in the library at St. Anselm’s, Moore’s counterpart for Miskatonic University. Hali’s Book is then brought to the New World by “fleeing Huguenot” Etienne Roulet, who, along with fellow occultists Hekeziah Massey and Japheth Colwin, establishes a secret organization based on Hali’s Book called the Stella Sapiente, which continues into the early 20th century.

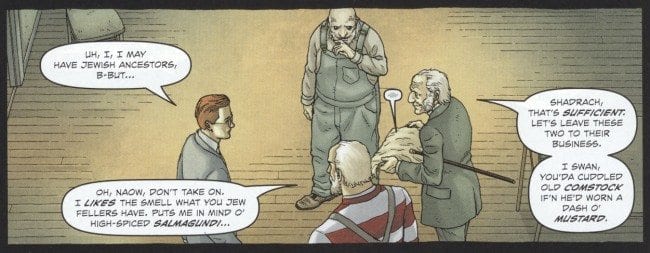

This history directly impacts Black’s investigation and the structure of Providence as a whole. Hali’s Book includes instructions on four ways to prolong human life beyond a normal lifespan: through cannibalism, through temperature, through “the revival of the flesh with philtres and decanted fluids,” and through body swapping, “the eviction of a soul so that a new inhabitant might occupy the emptied vessel, with its former occupant alike interred within the sorcerer’s unwanted former residence.” Throughout the first six issues of Providence, Black meets characters who, under the influence or inspiration of Hali’s Book, have tried to cheat death. In issue #1, Dr. Alvarez lives in freezing temperatures to stay alive, while in issues #5 and #6, Black meets Dr. Hector North, a scientist who, like Lovecraft’s Herbert West, experiments with serums and fluids to revive corpses. Further, the success of some of these life-prolonging methods is proven when an uncomprehending Black meets some of the figures associated with the Stella Sapiente, who have by 1919 lived for centuries. Shadrach Annesley, the captain of the ship that brought Etienne Roulet and his wife Mathilde to America, follows a cannibalistic diet, and compares Black to a tasty salad:

Cluelessly but predictably, Black misreads Annesley’s attention as a gay cruise, writing in his Commonplace Book that “the way he looked at me it was as if he’d like to just gobble me up—and who’s to say that I’d have minded?” Later in the series, in Providence #5, Black briefly rents an attic from Hekeziah Massey, who stays alive through a method not covered in Hali’s Book: inhabitation in those non-Euclidean dimensions outlined in Lovecraft’s “The Dreams in the Witch House” (1932).

In Providence #5-6, during his visit to Manchester, New Hampshire and St. Anselm, Black meets one final original member of the Stella Sapiente, Etienne Roulet, leading to a scene that returns us to the issues of sexual violence discussed at the beginning of this essay. Soon after arriving in town, Black meets a precocious thirteen-year-old girl named Elspeth Wade, who turns out to be Roulet, perpetuating his life though a centuries-long chain of body swaps. To prove his mastery of “the eviction of a soul” technique, Elspeth/Roulet lures Black to her/his home, where s/he inhabits Black’s body, forcing Black to become the thirteen-year-old girl. Then Roulet (in Black’s body) rapes Black (in Elspeth’s body), and soon after returns to Elspeth’s body. Here are two panels from the disturbing scene:

Again there’s a Lovecraft cognate: “The Thing on the Doorstep” (1933), where a mad sorcerer named Ephraim Waite first swaps bodies with his daughter Asenath, and then transfers his consciousness into Asenath’s husband Edward Derby. In the above panels, Roulet/Black mentions how he similarly invaded Elspeth’s father’s body—and left Elspeth to die as an old man—as part of a self-preservation method he’s practiced with dozens of bodies (including, initially, his wife’s) over nearly four centuries. Slightly earlier in the scene (and immediately after the body swap), Roulet responds to Black’s shock by noting that body transference “is a strange experience, is it not? One comes at last to question even the existence of identity as a phenomenon…” These are outrageously ironic words, since Roulet’s “eviction of a soul” method privileges his needs, desires, and selfhood above all others; exhibiting his selfishness, Roulet’s first act as Black is to whip out his penis (drawn by Burrows in the most matter-of-fact, explicit way possible) and rape a thirteen-year-old girl.

At the beginning of this essay, I argued that the instances of sexual violence in Moore’s work should be read in their specific narrative contexts, and this is also true of the rape of Black/Elspeth. One purpose of the scene is closure: the first six issues of Providence have been structured around Hali’s Book—the half-veiled rumors Black hears about the text, and the information readers piece together about the life-prolonging methods explained in its pages—so it seems fitting that in the same issue Black finally reads Hali’s Book, he is also confronted with the most horrible manifestation of its lore. (It’s difficult to predict what’s going to happen in the last six issues of Providence: now that Black realizes that the Cthulhuian magic of the Stella Sapiente is real, the dynamic of the series will change.) More importantly, the rape is Black’s “punishment” for his lack of empathy. He’s a character who relentlessly judges and privately insults (in his Commonplace book) most of the people in his life, and considers himself a sexual and intellectual “outsider” even while he constantly passes as a straight man to avoid the difficulties that a true outsider would endure in early twentieth-century American society. The migration of souls puts Black in the literal body of the Other.

Of course, this rape, and Moore and Burrows’ portrayal of the act, are complicated. As Tania Modleski argues about the role of sexual violence in Hitchcock, some portrayals of rape dramatize “the predicaments and contradictions of women’s existence under patriarchy” are enacted and exposed. This process works best if readers/viewers from a spectrum of genders identify with the victim. But can Black embody the “women’s existence under patriarchy” when he is only temporarily a woman? Do Black’s unlikable qualities, so much on display in the first five issue of Providence, limit or blur our sympathy for him? Is Moore’s use of rape to stage Black’s comeuppance troubling? Does it trivialize rape? Does Black deserve such a devastating punishment? His most egregious sin is ending his relationship with Lillian, which contributes to Lillian’s subsequent suicide: does this narratively “justify” the rape? And does it need to? Horror’s great theme is the manifest unfairness of life, where the innocent are raped and murdered for no reason at all—why should Black be spared the arbitrary pain and unfairness of the genre? Moore’s Providence body-shift rape is a provocation, a nest of questions without easy answers.

I can understand that a rape survivor—or someone connected to a rape survivor, or a sensitive reader—might prefer to avoid Providence, or might criticize Moore for the frequency of sexual violence in his scripts. I’d argue, though—just as Modleski argues about Hitchcock—that Moore is almost never simply titillating or exploitative, and that Providence is an example of his thoughtful story-driven treatment of such material. The rape of Black/Elspeth brings the “four methods of prolonging life” narrative arc to completion, gives readers a unique moment of horror, and most importantly forces Black to experience life (and abuse) as a woman, as one of the Others he’d been belittling in his Commonplace Book. Perhaps his experience as Elspeth will teach Black greater empathy, and provoke him to grow past knee-jerk Lovecraftian prejudices.

This moment of sexual violence also challenges Moore’s previous cosmic worldview. A deeply optimistic work in Moore's oeuvre is Promethea (1999-2006), the story of a mystical heroine who, in the middle of the series, takes a vision quest that reveals the Kabbalic structure of the universe. The end of Promethea’s journey comes in issue #23, where she and friend (and previous Promethea) Barbara Shelley reach the Godhead, the top sphere of the Kabbalah, and dissolve into the Oneness of all creation, represented in J.H. Williams and Mick Gray’ art as a circle of radiant white and golden light:

At its most basic, the “vision quest” story in Promethea implicitly asserts two metaphysical truths: that the universe is, at its core, a beautiful and good place, and that exploring this universe can lead to ultimate knowledge and peace. After these revelations, Promethea has one more arc to go—a more traditional narrative about a battle between two Prometheas and the end of the world—but these issues are a little dull: it’s hard to build suspense when we already know, on the macro-Heavenly level, that we are all redeemed.

Providence is the antithesis of Promethea's redemption. The body-swap between Black and Roulet, an event that blurs the boundaries between identities, is sudden and wrenching even before the rape, and not an angelic transformation into Oneness. Promethea’s paradise, the site of the dissolution of the ego, is located in Keter, the highest sphere of the Kabbalic sefirot, the lattice of divine order that structures the universe, but Providence shows the power of the sefirot turned into a source of perverse and corrupted power too. In the scene in Providence #4 where Garland Wheatley impregnates his daughter Leticia in an outsider attempt to create the “herald-man,” his head is framed by the lowest sphere of the sefirot, Malkuth, the realm of the physical:

Leticia is another rape victim—she "don't remember" much about sex with her father until Garland Wheatley is possessed by some malevolent, Kabbalah-derived spirit. Perhaps this power is from Malkuth, the corrupted physical sphere, the one furthest away from Keter and true transcendence. Yet Kabbalah scholarship has long asserted the interconnectedness of the spheres, pointing out that “Kether is in Malkuth, and Malkuth is in Kether”: Wheatley’s rape of his daughter is still a manifestation of the divine. Providence’s mysticism is the dark, hidden side of Promethea’s redemption, the site where love of celestial knowledge rubs up against the fear and celebration of ignorance in the famous opening paragraph of Lovecraft's story "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928):

The more merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The science, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Leticia's rape, and the rape scene in Providence #6, illuminates a tension in Moore's work between freedom of expression and the potency of language. On the one hand, Moore agrees with the Crumbian argument that comics are just “lines on paper, folks,” inherently distant from the real world and thus free to tell disturbing, immoral stories; this is his defense for the pederasty and bestiality of the final volume of Lost Girls (2006). On the other hand, Moore believes that language (and, by extension, media like comics that include words) can magically transform human consciousness and influence the world. Do words matter? Do lines matter? Do comics matter? Should artists follow their inspirations, no matter how perverse or taboo, or should they be aware of the real-life ramifications of their dreams made manifest?

Alfred Hitchcock: "Self-plagiarism is style."

These questions and controversies are expressed, of course, through aesthetic form. As I’ve talked up Providence among other comics fans, their opinions of Jacen Burrows have been wildly different, with some liking his cool, architectural approach, and others sorry that his art lacks gonzo energy. (One friend wishes that the splash page of Leticia’s rape had looked more “like a mind-blowing combo of Steve Ditko, Rory Hayes, and Henry Darger” and less like an airline safety brochure.) Perhaps one reason that Burrows’ art feels sterile is Moore’s decision to establish four long vertical pages—like the shape of a Cinemascope screen—as Neonomicon’s and Providence’s page grid norm. As Fritz Lang once famously said of Cinemascope, long horizontal frames are good only for “funerals and snakes"-- horizontal panels go against the verticality of the human figure, even when people are placed at the panel’s center or in symmetrical multi-person configurations. People are smaller and more fractured in a horizontal shape, and architectural and natural details fill up the fringes, creating a layout in sync with Lovecraft’s themes of the insignificance of mankind and the horrors at the periphery of perception. And Burrows’ sedate, photo-based imagery fits Providence’s slow progress towards Black’s sudden (and, through the rape, brutal) awareness of the ferocious veracity of Hali’s Book and the Stella Sapiente.

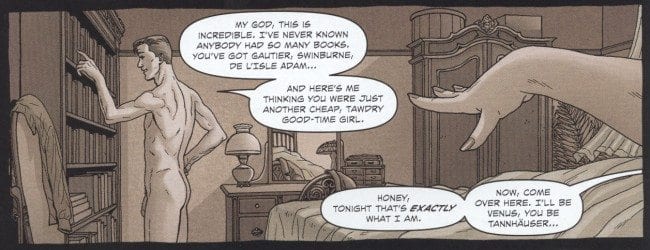

Given the thoroughness of Moore's scripts, however, Providence is very much his show, aesthetic and otherwise. After reading Moore for over three decades, I'm familiar with both the innovations he brought to the comics medium and the devices he re-uses in various works. One example of Moore repeating a technique is the hidden face of Lillian/Jonathan in the first issue of Providence. In the panel I presented earlier, as Lillian calling Black “cold,” we only see Lillian’s well-manicured hands, and this is true of every flashback of Black and Lillian alone. An earlier, happier moment of erotic intimacy, for instance, features Lillian’s hand and forearm in the right side of the panel, his wrist bent in a fey position:

During the present-day scenes of Lillian, dressed in male clothes, committing suicide at a death-assistance facility called an "exit garden" (a fixture in Moore's Lovecraftian alternate world), Moore resorts to other strategies to hide Lillian's face from us. The first page is a POV shot through Lillian’s point-of-view as he rips up love letters from Black and drops the scraps of paper into the reservoir. Lillian is shown from behind as he enters the exit garden in Bryant Park, and in extreme long shot—his face a Scott McCloudian smiley-face abstraction—as he sits in the suicide chamber, waiting for poisonous gas to kill him. All this tricky framing is Moore’s way of keeping Black’s homosexuality a surprise until the end of Providence #1.

This strategy is borrowed directly from From Hell (1999), where Moore and Eddie Campbell use hide-a-face staging in two instances: to delay our view of Sir William Gull until he becomes the monster who damages Annie Crook’s brain (at the end of chapter two, “A State of Darkness”), and to hide from us the identity of Mary Kelly, one of Gull’s would-be victims, as she escapes from Whitechapel, London, and Victorian patriarchal mysticism (as revealed at the end of chapter fourteen, “Gull, Ascending”). In all three examples—Gull and Mary Kelly in From Hell, and Lillian in Providence #1—Moore hides faces because each character needs to keep their true identity a secret. In particular, Mary Kelly and Lillian adopt camouflage to keep themselves safe in hostile, male-dominated societies, though Lillian is willing to give up the safety of his straight-man pretense for Black’s love, a sacrifice for love that Black is unwilling or too afraid to reciprocate.

Another repeated device: in “1969 / Paint It Black,” the second chapter of Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century, a villainous sorcerer named Oliver Haddo has the ability to prolong his life by transferring bodies with younger people, just as Etienne Roulet does in Providence, and a scene in “1969” is a direct precursor to the body-swap rape scene in Providence #6. In a flashback to 1947, Haddo, ailing in his original body, requests a private meeting with one of his disciples, the young Kosmo Gallion. Haddo indicates that he is dying (“I’ve taken…an untraceable poison…to guarantee it. The transference ritual…requires…a human sacrifice”), holds Kosmo’s hand, and steals Kosmo’s body:

Like the scene in Providence #6, the Haddo-Gallion transference is instantaneous—it’s barely a hiccup in the flow of a single sentence—and precedes rape; immediately after the above scene, Haddo in Gallion’s body follows up on his promise to “plough” Gallion’s fiancée by fondling her breasts in front of other members of the "invisible college." Roulet's swap with Black in Providence explicitly re-writes this scene, as a springboard for a much more brutal representation of sexual violence.

We could interpret Providence’s repetitions of hidden-face staging and mind transference as evidence of Moore’s creative exhaustion, if these devices didn’t function so well in context, and if Providence weren’t so compelling. Any predictability on the panel-by-panel level is offset by the thematic audacity and complex world-building of Providence. In issue #3, Salem native (and half-fish man) Tobit Boggs takes Black on a tour of the tunnel and pool that facilitated the fish-human miscegenation of Salem/Innsmouth, in a small scene shot through with connections to the key elements of Moore’s Lovecraft cycle. The tunnel and pool is where, eighty-eight years after the events of Providence, Lamper is murdered and Brears is raped. During his visit, Black is increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of fish/human species inbreeding and, consequently, with Boggs himself, who talks openly about his origins, about the obscene graffiti in the tunnel, and about how his wife “don’t mind it in the mouth or nothin.’" Black is disturbed by those illicit desires that—unlike his own homosexuality—can’t be hidden from mainstream society. Boggs is a real outsider, and the prejudices against him exhibited by Black and others will ignite into ultimate horror: in Providence #3, someone scrawls a swastika in front of the fish-people’s church, and Black has a nightmare that combines the Salem citizenry, transsexuality, the concentration camps, the exit garden where Lillian dies, and, perhaps presciently, Black’s own precarious position in a virulently normative society (“They’re Hebrewsexuals. They end up together in the showers.”).

The dream, the encounter between Black and Boggs, and almost every scene in Providence vibrates with dirty talk, with taboo images, with provocative ideas about prejudice and tolerance, and with the presence of Black himself, an unpleasant character whose jarring comeuppance brings the first half of Moore and Burrows’ comic to a provisional climax. There are six issues left, and I'll write about Providence again when the series is done. Issue #7 arrives at comic shops today, and I can’t wait. No comic twists my mind like Providence, and I'd recommend it to any readers that can stomach its extreme, and extremely well-crafted, vision.