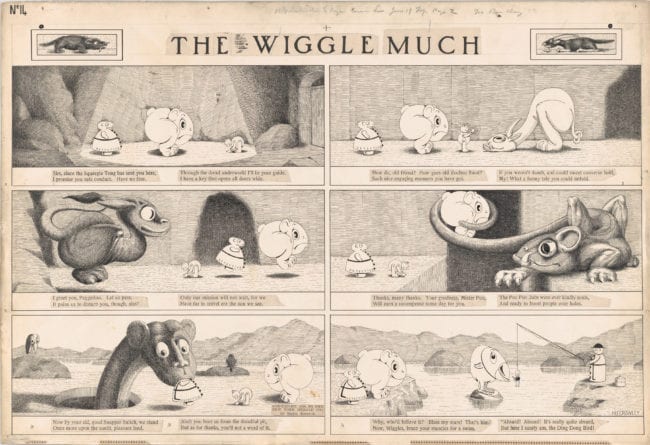

In 1973, the Newgarden family coffee table afforded little space for coffee, but an awful lot of coffee-table books, including one called Popular Prints of the Americas, a survey of printed Americana by Metropolitan Museum of Art curator A. Hyatt Mayor. Inexplicably showcased alongside the likes of Paul Revere and Mary Cassatt were a couple of Sunday comic strips, including a very dense and peculiar one from 1910 by Herbert Crowley entitled The Wiggle-Much. I was transfixed by that half-page for years, a profound mystery-strip which was never even hinted at in any of the standard reference titles of the day. Over the decades I managed to score a few tear sheets but little hard information, and when Dan Nadel began work on Art Out of Time (2006), Crowley and The Wiggle-Much were at the very top of my short list of recommendations. Now thanks to miracle of the internets, the universal butterfly effect has returned a feast from humble crumbs cast upon the waters so long ago. 2018 brings us a near coffee table-sized coffee-table book on Herbert Crowley and a tale as dense and peculiar as The Wiggle-Much itself.

Mark Newgarden: The story behind this book (which is in part embedded in its own text) is almost as fascinating the story of the artist himself. Who is Justin Duerr? Who was Herbert Crowley? How did the former encounter the latter?

Mark Newgarden: The story behind this book (which is in part embedded in its own text) is almost as fascinating the story of the artist himself. Who is Justin Duerr? Who was Herbert Crowley? How did the former encounter the latter?

Justin Duerr: I was born in 1976, grew up in rural Pennsylvania, dropped out of high school, and moved to Philadelphia in 1994. I've done lots of things to pay the bills over the years, including living as a squatter and not paying any bills. I worked on fishing boats in the Bering Sea, as a courier by foot in Philly, and as a housepainter and odd jobs person, which I still do. In between I've found time to make artwork, play music, and publish a zine. I got into art research in the 1990s when I became interested in the "Toynbee tiles," which are mosaic tile-works embedded in the asphalt of streets here, usually bearing the cryptic message "Toynbee Idea in Kubrick's 2001 Resurrect Dead on Planet Jupiter." Eventually a friend went on to produce a documentary film chronicling my years spent attempting to piece together what these things were and who made them. That no-budget, home-made movie was, shockingly, accepted to the 2011 Sundance film festival—and my friend, Jon Foy, awarded the prize for best director in the documentary category!

As for Herbert Crowley, I have to go back a bit — to 2008 or so. I was on tour, and the band was staying at a friend's place. My bandmate Kevin was paging through Dan Nadel's Art Out of Time and I overheard him remark to our host that he was sure I would become "obsessed" with something in that book. I'm really not a comics aficionado, and I only tend to get curious about things for which there is a dearth of information. I assume that if something has been published in a book, it wouldn’t beg further research. But, simply put, Kevin was correct.

I liked a couple things in that book quite a bit – particularly Rory Hayes (and I quickly learned there was an in-depth Rory Hayes book – by Dan Nadel.) But, when I came across The Wiggle-Much I was awestruck. It really had the strangest sway over me— immediately. It was just so obviously magical... whatever the heck was going on in that comic strip, it was profound, it was frightening, it was silly, it was austere, it was childlike and ancient... all at the same time. It seemed to be up there with Krazy Kat, idiosyncratically dealing with cosmic themes on the comics page, but also utterly unlike the Kat – not derivative or related to any other comic. Its influences were apparently some totally other art form, or something existing only in the mind of the artist. I feel that The Wiggle-Much is hardly even "sequential art" - it uses the comic strip format in a fundamentally different way. All to say, I fell totally in love with it. The artist, Herbert Crowley, was described as representing the largest "information gap" in the book – a book all about forgotten artists - and his birth and death years were indicated with question marks! So I really did become obsessed. I made it part of my life to research Crowley’s story and seek out examples of his work.

In 2011, when Resurrect Dead (the Toynbee tiles movie) was being readied for premiere, the director asked what he should include in a "where are they now?" segment at the end. I asked for something along the lines of "Justin is researching a new mystery – the lost artwork and life of Herbert E. Crowley." I hoped this might turn up leads. Meanwhile I kept plugging away. Eventually, a Philadelphia publisher who also knew of Crowley via Art Out of Time, saw the movie and noticed that spot at the end. Josh O'Neill emailed, and a few days later (in a phone conversation that lasted for hours) he became sold on the idea of Beehive Books publishing something on Crowley. So in a roundabout way, that little blurb lead to the creation of the book!

Please explain how this project took hold. What was it about Crowley? I’m curious what propelled you, what you expected going in and what sustained you as you began to dig. At what point did you realize there was no turning back?

I should point out that I never went into any of this with the expectation that there would be a book. I just wanted to connect some dots of history that seemed to be pleading to be connected. I honestly began to feel as if these spirits of the past were driving me on, compelling me to do this. I had several hair-raisingly uncanny experiences during the course of it all.

One of the most inexplicable is that Herbert Crowley and I both independently created characters named “Esmeralda de Gabrielle.” I used a character with this name in some of my artwork in 2012, two years before I was in Zurich and saw Crowley’s notebook, which contained a short sketch for a one-act play called Recitations for Frida. It begins “This story is of the 12th or late 14th Century - It was discovered among a series of Troubadorials collected by Esmeralda de Gabrielle – […] She was banished from St. Jean de Luz and went to England - She amused herself by making a collection of Ballads. There are 30,000 of them - this is one of them.” My own character was a “mystic record keeper” and a scribe, a sort of supernatural librarian deity. When I saw that notebook the hairs on my neck stood on end.

My research took me to Ohio, Texas, and Switzerland. In 2015 I had a crazy adventure at The Brocken – the artist's commune in Rockland County, New York where Crowley lived from 1909 to around 1915, and where I literally dug up 100-year-old letters and artwork from a rotting, collapsing house. This was also where my wife Mandy found a Herbert Crowley print; the 1916 Sunwise Turn broadside – in a raccoon nest!

The Wiggle-Much (perhaps one of the most obscure comic strips to ever appear in a NYC newspaper) is considered Crowley’s “best known” work, and yet is almost a footnote to a remarkable, completely lost career in the arts. Can you give us some idea of the length and breath of this career and where does the strip fit in?

Herbert Crowley was born in England in 1873 and trained to be an opera singer. Struggles with stage fright meant his singing career never really began, but he refined his powers as an imaginative visual artist. He traveled all over the world and at various times lived in New York, Paris, Toronto, and London. His comic strip, The Wiggle-Much, ran for fourteen weeks in the New York Herald during 1910. He ceased exhibiting his work and dropped off the radar of the art world after serving in WWI in 1917 to '18. He died in 1937 in Zurich, Switzerland, where he and his wife, Alice Lewisohn, had become part of psychologist Carl Jung's inner circle.

I agree that Crowley himself and those around him would have thought of the strip as a footnote, but in retrospect it is one of his most powerful works. One thing I find compelling about it is that it may have somewhat forced Crowley out of his comfort zone of separating his gloomy and lighthearted work. He rarely dated his work, but one of the few that he did date is a 1902 drawing of — a Wiggle-Much! He drew that creature (or creatures; “Wiggle-Much” is both an individual being and a species name) for his entire life. It wasn’t something he created just for the Herald. But he almost never introduced the Wiggle-Much into his symbolist landscapes or more serious artworks.

I’d be speculating, but I suspect in today’s parlance Crowley might be diagnosed as “bipolar.” He tended towards extremes, talking about suicide one day and bubbling and energetic the next. Sometimes one can sense the shift in the course of a single letter. This is clearly reflected in his artwork. The book is more or less split in half, with the first half of the book comprising his childlike puppet show sort of work, and the second half, the more austere, funereal pieces. In certain sublime moments of The Wiggle-Much he combines the two – perhaps because he wanted to do something more serious but had a looming deadline. But he would usually just turn work down if it didn’t fit his current mood. There’s a 1915 letter to his art dealer Martin Birnbaum where he writes, “It is awfully jolly of Mr. Martin Johnson of Harper’s Bazaar to want some of my work. But just at this time I do not feel particularly funny. In fact I have become intensely serious.”

As for the trajectory of his “career,” the comic strip was a non-entity. It was never mentioned in any of the press releases for his gallery shows, even when artwork featuring the characters was included! I think it may have been considered a liability – a fear that perhaps his comic strip would cause potential collectors to not take him seriously as a fine artist. I’m not really sure.

Mary Mowbray-Clarke mentioned in her diary that a toy manufacturer had expressed interest in marketing the Wiggle-Much… but they wrote at a time when the strip was near cancellation, and the company itself seems to have never gotten off the ground. The Wiggle-Much seemed to be a commercial venture, which yielded great art and not the other way around. As for the rest of his art career, I think there is a massive amount of lost work. Some was destroyed, and some still probably exists unseen.

And his career seems to have been cut short by the war?

I think Crowley had a twofold reason not to exhibit after WWI. One, his “nerves” were even worse than before the war. I don’t think he saw active combat, but London was bombed – Crowley didn’t need to be on the front lines of the gas attacks to experience what we’d call PTSD today. He already “suffered from nerves” and it’s easy to imagine him simply not able to deal with an art exhibit opening, let alone the organizing, logistics and networking. Additionally, he married someone who was willing to support him, so he didn’t need to sell. Tellingly though, he never ceased making artwork. Given that he generally didn’t date his art and that he would occasionally destroy it when he was having a “black mood,” one can see how hard it is hard to get a real handle on his artistic trajectory.

Exhibit catalogs are the best way to date his work created prior to 1917. I believe that most if not all of his finely detailed “temple” drawings have been found – whether as prints or originals. The moody, gothic pieces are the most unaccounted for. There are a few “masterpieces” that are currently lost, work that his friends referred to as some of his best but which have never been found. One, Butterflies, I think went down with The Brocken. There’s supposedly a remarkable later work featuring a Christ and Devil figure in the collection of the Swiss-born New York artist, Ugo Rondinone, with whom I’ve never been able to make contact. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a handful of good pieces that weren’t used in the book for reasons of space and budget - about thirty really stellar ones, mostly in his more somber style. One of the really beautiful things about bringing all this history and art to the surface is that it feels like it’s not just a rediscovery, but also a new beginning.

Temple of Love, 1911–24

Beyond the historical aspect, how does Crowley's work speak to a 21st century audience?

Oddly enough, I think we live in a similar era now in that we're experiencing seismic social shifts, partly as a result of changing technology. The world now, as then, feels like it's being turned inside out as modes of communication change faster than our rules of etiquette or expectations of social conduct can adapt. I think the introspective, largely ascetic spiritualist movements of Crowley's era - Westerners interest in meditation, Theosophy and related sects, theories of synesthetic correlations between sound and color etc. were popular partly as an attempt to counter the overwhelming "information glut" that people of the early 20th century often described. Obviously conditions are similar now and we see many of the same impulses: "back to nature" sentiment, interest in transcendent, direct spiritual experience etc. There was a time in the 20th century when Crowley's style of artwork was out of fashion, when figurative, idyllic or fantasy-based work was derided for its perceived lack of machismo and was overtaken by more cerebral artforms. But times change. Crowley's era and our own have many correlations, and I think people are once again thirsting for visual art that seems to be an "antidote" to the evils or pressures of a time that "feels" similarly disorienting. We may live in a time strange enough, once again, to understand the essence of Crowley's work.

Can you tell us something about your next project?

The new book I’m working on focuses on the same period, with Crowley’s close friend Mary Mowbray-Clarke at its center. (Her brother Stephen was not only the former art director at the New York Herald, but invented the half-tone printing process!) Mary had a hand in just about every avenue of the arts you can imagine. I’ve been unbelievably lucky to uncover an absolutely staggering archive of her papers including never-before-seen letters and documents regarding the organizing of the 1913 Armory Show. I feel sort of required to write Mary’s story at this point! I want her book to have a William Morris sort of design, as she was a huge and lifelong William Morris fan. I have no idea who would publish it – but it’ll take me a year or three to get it all together, so that’s a worry for another day!