Welcome to the first installment of "Monsters Eat Critics," a monthly column I'll be writing for TCJ.com. I hope that "Monsters Eat Critics" sounds like the title of a Z-grade science-fiction movie, because I plan to write about genre comics, including science-fiction comics, rather than the alt-, art- and mini-comics so ably covered by other TCJ critics. Let me make clear, though, that I'll be saying little about contemporary superhero comics, because I'm bored by the ones I've read and have nothing to express about them beyond a shrug and an annoyance that hype like "The New 52" gets so much attention, even negative attention, on comics blogs. Even though future columns will discuss creators who simultaneously labored in and transcended the superhero genre—we'll trot Kirby out for obligatory analysis, if only to rile Pat Ford—I don't care about superheroes or the superhero-driven business of American mainstream comics. I'm looking for art in other genres, and I'll begin with one of the most artistically accomplished genre comics of the last ten years, Naoki Urasawa's Pluto (2003-2009). Specifically, my argument is that Urasawa builds Pluto on overlapping, complex systems of doubling, and in reading closely to uncover these systems, I’ll be giving away all of Pluto’s major plot points, so beware. We spoil to dissect here.

I've always found "doubling" to be a lit-crit concept best understood through specific examples. Cinema's poster boy for doubling, for instance, is Alfred Hitchcock, and several critics (François Truffaut, Donald Spoto, Mladen Dolar) have pointed out the connections, repetitions, and mirror-images wired into Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943) in particular. After its opening credits, Shadow begins with an image of an iron bridge spanning a river, which then dissolves to a distant shot of the bridge that encompasses an urban skyline in the background and a car wreck in the foreground. These shots establish the film's initial locale as an urban slum, and are quickly followed by a sequence that narrows our attention to a specific street, a specific apartment window, and a specific character important to Hitchcock's story:

The man on the bed is "Uncle Charlie" (Joseph Cotton), a psychopathic killer (the Merry Widow Murderer) who, over Shadow's next five minutes, will escape from two police officers. He will then dictate a telegram over the phone to his sister Emmy in Santa Rosa, California, to arrange a visit, and a safe place to hide, with his sister's all-American nuclear family.

As Charlie finishes his telephone call, Hitchcock cuts to an establishing shot of Santa Rosa, and follows with closer views of both the town's busy main street and a smiling police officer (so different from the cops hunting Uncle Charlie) directing traffic. And then once again Hitchcock shows us a street, a window, and a figure on a bed:

The girl is Charlotte "Charlie" Newton (Teresa Wright), named after her uncle and clearly a doppelganger for him too. Uncle and niece are introduced through the same shot sequence, and both express ennui as they recline on their beds: uncle is sick of his life as a fugitive, and niece is tired of the boredom of small-town Santa Rosa. (Of course, boredom isn't a problem after Uncle Charlie comes to town.) Hitchcock "doubles" the two Charlies up, defining them as psychically, almost telepathically, linked. Hitchcock continues this doubling throughout the first half of Shadow, and even hints at incestuous attraction between the two, only to shatter their bond when niece Charlie uncovers her uncle's murderous past.

I'm not bringing up Shadow here to argue that the doubling in Pluto is somehow Hitchcockian, though Pluto does incorporate elements of murder mysteries and police procedurals. Rather, Hitchcock reminds us that doubling can crop up in many ways in a text--Hitchcock overlaps dissolves, camera movements, figure placement and dialogue to link the Charlies in the opening sequence of Shadow--and comics critics hunting for doppelgangers and repeating motifs should look at plot construction, changes in the visual register, and a thousand other formal elements. I'm not as sharp a close reader as the Hitchcock critics previously mentioned, but nevertheless, below is my initial attempt to understand Urasawa's networks of doubling in Pluto.

Doubling is at the heart of the Pluto project: Pluto is Urasawa's rewrite (with co-author Takashi Nagasaki) of Osamu Tezuka's most popular Tetsuwan Atom/Astro Boy story, "The Greatest Robot on Earth" (1964-65). In other words, Pluto is "Ultimate Astro Boy," and Urasawa was encouraged by Macoto Tezka, Tezuka's son and the head of Tezuka's estate, to take liberties with "The Greatest Robot on Earth" in the re-telling. One obvious change is in the length: Tezuka's original is 180 pages long, while Urasawa's version stretches over 1500 pages and eight volumes in the Viz English translation. (All future page numbers are from the Viz books.) The rise of decompressed storytelling in the post-Tezuka mangaverse partially explains Pluto's epic length, though Urasawa also adds new characters, plotlines and incidents to Tezuka's canonical story. Pluto is a souped-up double to "Greatest Robot," a celebration of Tezuka's popularity (its serialization in Big Comic Original began in 2003, in honor of the year of Atom's fictional "birthday") and a comic created under the anxiety of Tezuka's influence, a palimpsest that drastically reconfigures Tezuka's tale.

Atom is the perfect lead character for a re-booted, re-told narrative, since his origin story is a commentary on the promises and dangers inherent in copying and doubling. Atom is a robot built by Dr. Tenma, the head of Japan's Ministry of Science, to replace Tenma's son Tobio, who died in a car accident. Physically, Atom is Tobio's identical twin. Tenma's plan to mitigate his grief fails, however, when he realizes that Atom lacks some essential elements of "humanness" that belonged to Tobio, such as an appreciation of natural beauty. (In one scene in Tezuka’s first Atom story, Atom prefers to study geometric cubes rather than flowers--and as we'll see, flowers are a central symbol in Pluto.) Disillusioned with Atom's inability to copy Tobio, Tenma cruelly sells Atom to a circus, where eventually he is discovered and adopted by another genius, and the successor to Tenma as the head of the Ministry of Science, Dr. Ochanomizu.

Pluto includes a flashback to Atom's origin, and Urasawa drastically rewrites Tezuka. In Act 39 (each serialized chapter is an Act, and there are 65 Acts in Pluto), we see Tenma and Atom quietly eating dinner together, soon after Atom is brought to life. During the meal, Tobio/Atom talks about cleaning his room, and about looking at a book of insects that includes "a really cool picture of a butterfly called a Zephyrus" (Volume 5, 148). Atom also enjoys the food he's eating. Urasawa's Atom recognizes the beauty of butterflies and the flavor of food, and he is obedient and eager to please, engaging in as much conversation as Tenma will tolerate. Which isn't much: Tenma still rejects this copy of his son, because the real Tobio never cleaned his room, because Tobio wasn't interested in butterflies, and because Tobio didn't like the food Atom found tasty. The Act concludes as Tenma boxes himself into a chilling logical corner, noting that he was a strict disciplinarian with his dead son ("I used to severely scold Tobio all the time," says Tenma, Volume 5, 169) and that if Atom were a faithful copy of Tobio he'd hate his father's guts:

This scene subverts the typical science-fiction stereotype of robot-human interaction. The emotionless robot is Tenma, who delivers devastating lines like "Tobio hated me" in a muted voice (note the ellipses), and who casually cuts his meat while cutting Atom out of his life. Atom looks on, wide-eyed and heartbroken. (Men without emotion, robots who cry--a major theme of both Tezuka's Atom and Urasawa's Pluto is the permeability of the distinction between humans and robots.) Ten years before Spider-Man, Atom's origin is a story of familial loss, and solace found in a non-nuclear surrogate family, but it's also a postmodern critique of the notion of essences: if Tenma could get beyond defining Atom as a (failed) copy of Tobio, and see Atom as an aleatory but exceptional hybrid of human and machine, he would gain a loving son. Both Tezuka and Urasawa claim that sometimes a copy can be unique and better than the original, a ballsy claim on Urasawa's part, given his "copying" of "The Greatest Robot on Earth." This claim is just one of Pluto's multiple meditations on the nature(s) of doubles, copies and doppelgangers.

Another doubling that hovers over all of Pluto is, oddly enough, the Iraq War. Urasawa's version of the USA is the United States of Thracia, an imperialist state secretly controlled by Dr. Roosevelt, a malevolent but immobile supercomputer that speaks through a bow-tied teddy bear. (Apparently this teddy bear was a villain in the 2003 Japanese Atom anime, and I love how Urasawa connects the name "Roosevelt" to Thracian domination.) Thracia's main enemy is Urasawa's Iraq cognate, The Persian Kingdom of Central Asia, and Thracia-Persian tensions explode before the present-day events of Pluto, when Thracia falsely claims that the despotic Persian ruler King Darius XIV has "robots of mass destruction" (Volume 2, 59). A band of Thracia-sponsored scientists called the Bora Study Group (i.e. UN inspectors) enter the Persian Kingdom to investigate, and even though the scientists (including Dr. Ochamomizu) uncover a graveyard of broken robots under Darius' palace, they find no hard evidence to back up the "mass destruction" charge. Thracia still declares war, however, and their super-powered robots reduce the Persian Kingdom to dust.

Many of the events in Pluto are a direct result of this war. The Thracia-affiliated robots that fought in the war are being systematically demolished by an unseen but seemingly unstoppable antagonist—that’s Pluto--and (in yet another instance of doubling) the human members of the Bora Study Group are also being killed off, one by one. These murders, and various characters' attempts to solve these murders, push the story forward, but I find the correspondences Urasawa draws between the fictional Thracian-Persian conflict and America's real-life invasion of Iraq even more compelling than the mystery plots. Urasawa is pissed about US imperialism. He clearly believes that US claims of Iraqi "weapons of mass destruction" were a blatant lie, and he shows us the innocent lives lost because of the Bush administration's policies of torture, secrecy and media manipulation. In one flashback, we see Pluto's main character, the robot police inspector Gesicht, serving as a soldier in the "Peace-Keeping" unit of the Thracian invasion force, as he is confronted by an anguished Persian father:

This scene connects on multiple levels with other moments and themes in Pluto. Images of dead children thread throughout the book, and it's the death of his family, including his children, that incites Pluto's master "villain," Professor Abullah, to kill the super-robots and bring down Thracia. In making his bad guy a victim of Thracian/US aggression, Urasawa denounces post-9/11 Bush-era America and reminds us of a broader truth: that suffering doesn't always ennoble those who bear its pain, that suffering can make a person unstable, broken, monstrous, inhuman.

Urasawa's boldest revision of "The Greatest Robot on Earth" is his elevation of Gesicht to the role of leading man. In Tezuka's original, Gesicht is named Gerhardt, and he's "a robot investigator from Germany," a bit player who enters the narrative and is torn apart by Pluto within ten pages. Although Gerhardt has a humanoid shape, certain features (his helmet-like head, his prismatic eyes, gun barrels embedded in his chest) identify him as a machine. Urasawa's Gesicht, however, passes as a human being to the untrained eye. The first Act of Pluto introduces Gesicht ("face" in German) as a man who sleeps, dreams, loves his wife, and works as an agent for Europol, so it's a small surprise, at least to readers unfamiliar with "The Greatest Robot on Earth," when Gesicht announces "I'm a robot!" and re-shapes his left hand into a gas gun when subduing a perp (Volume 1, 24). Urasawa keeps us very close to Gesicht; we learn most (but not all) of the information about the robot and Bora murders through Gesicht’s investigations. Though Urasawa frequently shifts his story away from Gesicht's point of view, to present different characters, locales and time periods, Gesicht is the primary locus of our attention and sympathy, which makes it all the more tragic when he's murdered in volume six of Pluto.

After he establishes Gesicht as the anchor of the story, Urasawa spends the rest of Pluto doubling Gesicht with a variety of characters and situations. One example: both Gesicht and Pluto have alterations forced on their bodies and minds by unscrupulous scientists. Throughout Pluto, Gesicht uncovers evidence that sometime in the past he murdered a human—an unpardonable violation of the Laws of Robotics that govern Urasawa's fictional world—but that his memory of the crime has been wiped from his brain by Europol bosses who have made a "huge investment" in him and want him to remain an active officer (Volume 2, 153). A key scene occurs in unlucky Act 13, as Gesicht plans a holiday in Japan for him and his wife. Gesicht discovers that he’d cancelled reservations for a Japanese trip two years earlier, though neither of the robots recalls making those reservations. Instead, they supposedly went to Spain, and in some of their travel photos posed together in expansive fields of sunflowers:

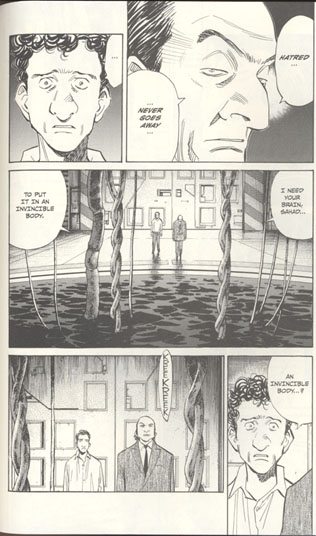

These shared memories of Spain turn out to be false, fabrications of Europol's tinkering with both their A.I.s to erase evidence of Gesicht’s murder. It’s important that Urasawa draws flowers at the moment of Gesicht’s dawning realization, because Pluto—a robot also rebuilt to deviate from his original programming—is a caretaker of flowers and plants. Pluto’s name is Sahad, and initially he is a robot scientist researching ways to turn the deserts of the Persian Kingdom into cropland. Sahad meets with some success, until the Thracian invasion decimates the new growth and instills in King Darius and Professor Abullah the thirst for revenge. Abullah implants Sahad's consciousness in a new, invulnerable body, the Pluto body:

Even after Sahad becomes Pluto, however, he continues to love plants. In Acts 21-23, Uran, Atom’s robot sister, befriends a disguised Sahad/Pluto in a Tokyo park. Sahad has temporarily placed his A.I. in a humanoid body, and lives like a vagrant in the park, using his skills to paint abstract pictures of flowers and to prompt the growth of living flowers:

Urasawa uses flowers, then, to connect Gesicht's involuntary loss of memory with Sahad's metamorphosis into Pluto. Flowers remind Sahad of his idyllic previous life as a botanical robot, before he was rebuilt into a killing machine, and flowers represent for Gesicht the false (but comforting) memories that masked the murder he committed. Both have lost innocence.

Besides Pluto, perhaps the most obvious doppelganger for Gesicht is Brau 1589, a creepy, damaged robot imprisoned in the basement of Europol’s Artificial Intelligence Correctional Facility for exactly the crime hidden in Gesicht’s past, killing a human being. Gesicht visits Brau 1589 to glean ideas about the robot and Bora murders, and in these scenes Urasawa steps outside of “The Greatest Robot on Earth” for inspiration: the discussions between Gesicht and Brau are reminiscent of the sinister, flirty conversations between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. The connections between Gesicht and Brau (and other robots) are aided by a fictional contrivance: in Urasawa’s science-fiction world, robots can easily remove and swap their memory chips. In Act 15, when Gesicht and Brau share memories, Brau cuts through the fabricated trips to Spain, immediately accesses the details of Gesicht’s crime, and gives readers a hint of Gesicht’s motivation for committing murder. As we realize much later in Pluto, Gesicht killed a sleazy anti-robot criminal who had kidnapped and murdered Gesicht’s own little robot boy. A chain of dead children connects Gesicht with Tenma and Abullah, a chain made explicit by Gesicht’s fever dream in Act 28 where various details—the death of Tobio, the activation of Atom, the incongruous presence of Helena at Atom’s birth (speaking a line about their own robot child that we later see in a flashback), the metamorphosis of Atom into Gesicht’s dead child, and the distraught Persian father Gesicht met as a soldier—condense into a single symbolic vision of guilt and grief:

Other robots try out new memory chips in Pluto, which lead to other instances of doubling. Professor Abullah, the scientist who constructed the Pluto body for Sahad, is himself a robot. The flesh-and-blood Abullah dies during the Thracian invasion, but not before his memories are transferred onto a chip that Tenma implants into a robot twin. This event is the cause of much of the violence in Pluto, because the overwhelming emotion the Abullah-robot inherits from the human Abullah is hate—hate directed at the Thracian forces and robots that decimated the Persian Kingdom and killed the members of his family. (In a twist that echoes Gesicht’s false memories, the robot Abullah mistakenly believes that he is a human with several cyborg prostheses, until Tenma tells him the truth.) Atom likewise receives a memory-chip transplant from Tenma, after a battle with Pluto leaves Atom damaged and comatose. To jolt Atom back to life, Tenma inserts the memories, traumatic and otherwise, of the murdered Gesicht into Atom. Tenma and Ochanomizu fear that Atom, like Abullah, will come back to life filled with rage, but Gesicht’s better nature triumphs. At the moment of his death, Gesicht was at peace, secure in his belief that “nothing comes of hatred,” and it’s this sense of peace that Atom carries into his final battle (and truce) with Pluto. The story is bookended, then, by two memory-chip exchanges, one that symbolizes the wounds of the Persian/Thracian War, and another that councils forgiveness and promises redemption from the wars and tortures that define the 21st century in both Urasawa’s world and ours.

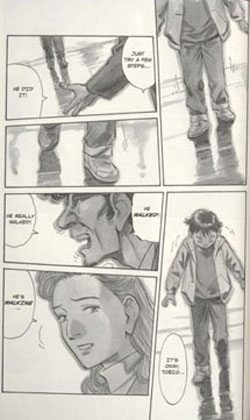

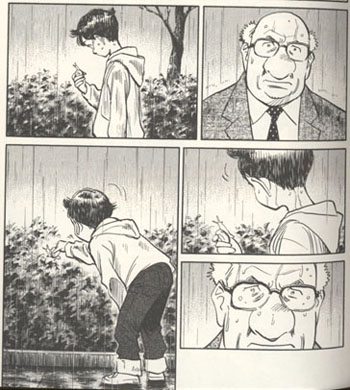

The last type of doubling I’ll discuss is Urasawa’s repetition, sometimes with variation, of specific narrative situations. Pluto begins with firefighters battling an inferno ignited when Pluto destroyed the super-robot Mont Blanc in a Swiss forest, and ends as Sahad/Pluto saves the world by freezing dangerous pollutants in a pillar of ice. (These complimentary scenes have an eschatological feel—“Some say the world will end in fire / Some say in ice.”—that nicely fits the apocalyptic vibe of volume eight.) Graffiti is a persistent motif: Sahad/Pluto paints flower murals, as does King Darius when he warns Thracian soldiers and Gesicht of Pluto’s power, and when Atom is reactivated, he scrawls the formula for a doomsday bomb all over his room at the Ministry of Science. And even the smallest repeated gesture by a character in Pluto can be freighted with significance: in Act 7, Gesicht first recognizes Atom among a group of school children because Atom examines a snail he finds on the sidewalk, and then places the snail in a bush without harming it. (It’s another symptom of the porous boundaries between human and robot that Gesicht identifies Atom based on his greater capacity for mercy.) Atom repeats the same gesture in volume eight:

This repeated gesture is a minor climax in Pluto, because after his resurrection, Atom behaves erratically (see bomb formula, above) and Dr. Ochanomizu fears that this new Atom might be bloodthirsty or insane. But his kindness toward the snail proves that Atom is “all right now” (Volume 8, 49).

One scene in Act 1 anticipates many of the doublings and themes that stretch across all of Pluto. After capturing a criminal who beats a police robot to death, Gesicht has the unenviable task of conveying the bad news to the robot’s widow. While trying to process her grief, the robo-widow talks about a little boy who “cried and cried for days” after the death of his pet dog, and concludes that now, for the first time, she understands how the boy felt. This scene directly connects with Act 24, a sentimental chapter where Dr. Ochanomizu tries (and fails) to rebuild an obsolete robot dog—and Act 24 ends with one of Abullah’s emissaries smashing a different police-bot apart. But during his earlier talk with the robo-widow, Gesicht volunteers to erase part of her data, and her response is as poignant as her metal face is deadpan:

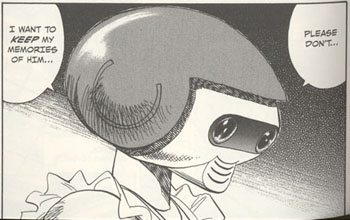

Gesicht’s offer to alter the widow’s data alludes to his own violated memories, of course, but it also prefigures Helena’s situation after Gesicht himself dies. Two months after Gesicht is murdered, Helena and Gesicht’s creator Professor Hoffman visit Tokyo, and meet with Dr. Ochanomizu. While Helena puts on a brave face and feigns losing herself in the sights and sounds of Japan, Hoffman quietly tells Ochanomizu that he asked Helena if “she would like to have some of her memory erased.” Her answer, in Hoffman’s words: “Said she didn’t want to lose a single memory of him.” Now Gesicht is the dead cop, and Helena the robo-widow, clinging to her recollections.

I’ve barely begun to examine Pluto. I don’t talk at all about how Pluto functions as an adventure story—probably because this is the least interesting aspect of the story for me—but I’m sure fans of superhero comics would find it fast-moving and entertaining. And although Pluto is one of the most unabashedly sentimental comics I’ve ever read, I don’t devote any words to its torrents of human and robot tears. Perhaps I should’ve discussed Pluto’s flaws, the biggest of which is a loss of momentum in the last two volumes after the death of Gesicht— Urasawa makes Gesicht such a compelling character that the narrative never recovers from his passing. (It’s similar to the falling-off I feel reading Death Note.) What I’ve written convinces me, though, that it’s a magnificently complex comic, and I’m grateful to Urasawa for his structural doubles, for his righteous anger over American foreign policy, and for the sheer chutzpah of rewriting Tezuka in the first place, and arguably doing a better job. I began this column by discussing Hitchcock, and I chose my example of doubling from Shadow of a Doubt partially because later Hitchcock films are almost dauntingly complex. In a masterpiece like Vertigo (1957), Scottie doubles for Madeline who doubles for Judy who doubles for Carlotta who doubles for Midge and the movie becomes a corridor of infinitely receding mirrors. I sense the same depths in Pluto too. As I contemplate what Urasawa’s accomplished, I get dizzy.