His name may be synonymous with high art, but Pablo Picasso's life was also steeped in comics. He grew up reading them, he drew them and saved them – and, as with everything he loved, he learned from them. First in Spain and later in Paris, cartoonists were part of those cliques which shaped his work. It was Picasso who convinced one of them, Juan Gris, to trade in caricature for Cubism.

These days Picasso himself is a cartoon. He's that bulb-headed man in the striped T-shirt, always turning beautiful women into three-eyed beasts. This persistent image is something "Picasso and Comics", at Paris' Musée Picasso, confronts and corrects. Says the museum's president Laurent Le Bon, "If E.P. Jacobs or Art Spiegelman decides to make an allusion to Guernica, they know people are going to get the reference. But, when it comes to comics, Picasso remains most attractive as a character."

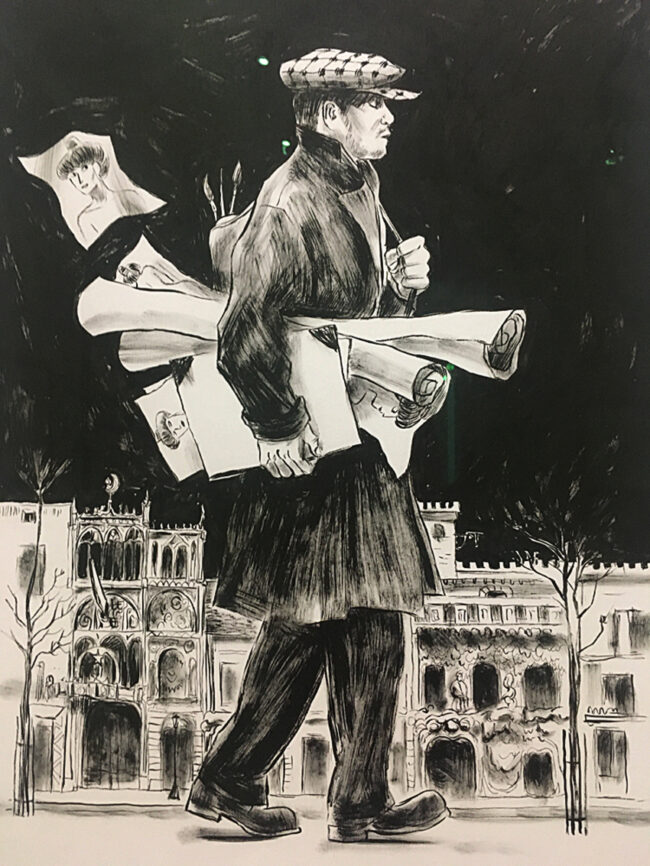

Picasso and Comics is filled with proof of this. It abounds in storyboards, sketches and murals, all of which feature the painter. Both historic and up-to-the-minute, they come from names like Art Spiegelman, Gotlib, François Olislaeger and Milo Manara. But the show's real interest lies in smaller, subtler things: Picasso's homemade zines and the fading comics he kept. It's here that surprises arise to change the stereotypes.

When he moved to Paris, Picasso was 23, another poor foreigner who hardly spoke a word of French. Early on, his assets were limited. He had a lively girlfriend called Fernande Olivier, a devoted pal in the poet Max Jacob – and a small network of supportive fellow Spaniards.

Within four years, however, Picasso was running the avant-garde. He was that good, that determined and, somewhat implausibly, that charismatic. No one ever learned any more from other artists yet Picasso cherished the everyday. He loved dogs, loud ties, men in sandwich-boards and the crude, colorful prints called Images d'Epinal. He saw the circus every week and hoarded every type of paper. He kept old Catalan comics (such as the 1860s pioneer Un Tros de Papier) but he also wrestled with the English of Little Jimmy. In notes for a never-published memoir, Spanish artist Ricard Opisso remembers this Picasso as "naughty, happy, hot and rebellious…. someone who spoke very little and listened a lot."

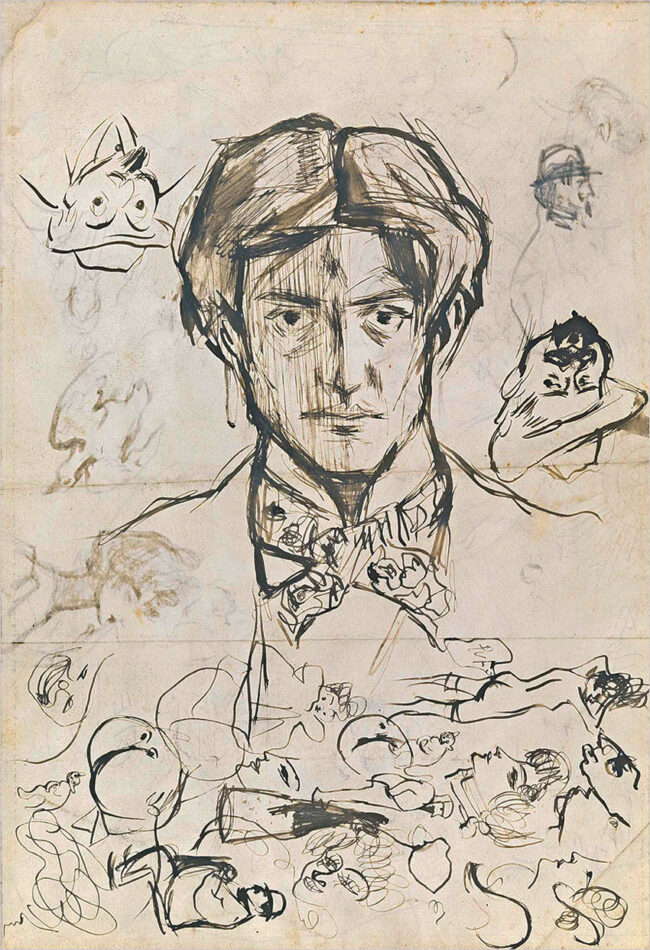

A fuller portrait is available in Pablo, the four-volume French BD that debuted in 2012. (It is now out in English). Written by Julie Birmant and drawn by Clément Oubrerie, Pablo is a landmark. Oubrerie's originals – along with a giant portrait – are one of the show's absolute treats. Others come from Catherine Meurisse, Daniel Torres, José Muñoz, Nick Bertozzi and Enki Bilal. (There's even a cover from L'Epatant which, although drawn in 1933, looks for all the world like a Gary Panter.) Most of what seems really comfortable next to Picasso comes from greats of the past, such as Hergé, E.P. Jacobs and Jean-Marc Reiser.

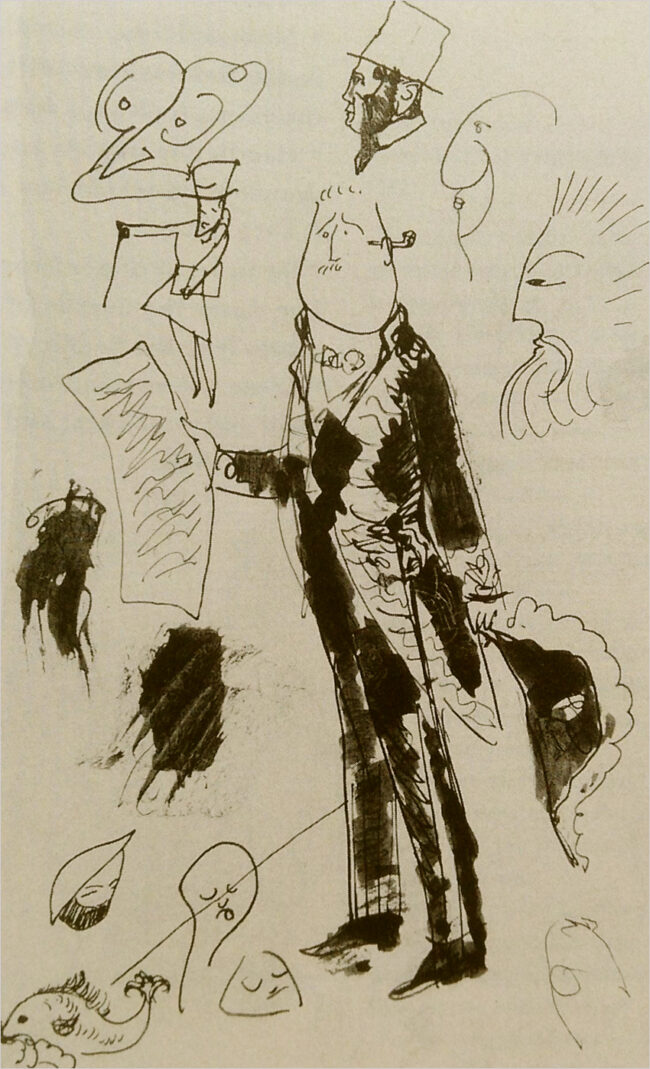

Picasso's comic connection sheds plenty of light on his talent. Here was a creator who, for eight decades, never gave up his interest in caricature. Yet his own comic drawings, many of them long private, always remained the work of an artist. As critic Werner Hofmann puts it, all Picasso's cartoons have "a rebelliousness of form that makes no attempt to comment critically on society…[instead] they aim profoundly to examine the practice of art."

Much of this came out of Picasso's Spanish heritage, which was the product of three different regions. Starting with "comics" he created as a child (two examples are on display), the artist grew up with a special brand of graphic grotesque. This, says historian Valeriano Bozal, informed his whole creative life: "These youthful efforts…represent a line of development Picasso never abandoned…The way he approached the comic and the grotesque is original and his images, while they owe much to the past, are always new and unusual. But this novelty and originality are surprisingly underpinned by a tradition that provided perspective and limits."

Picasso lived from 1881 to 1973; he spent 68 of those 91 years in France. His work gave birth to much of the "modern" in modern art. Yet, as time passes, the universe which formed him has grown increasingly distant. Its population lived much of their lives in the streets, taking part in a wide range of dramas and characters. Their "genteel classes" had bourgeois aspirations and cared deeply about the rules of church and state. Its men were clad in sober black and all its women corseted. (Picasso once rented out studio space from a corset firm where, in order to watch the workers, he punched in eyelets.)

The Spain in which Picasso grew up was progressive and it tried to improve sewers and literacy. But only ten years before the painter's birth, three-fourths of its population could not read. Political tensions were also endemic. In 1898, when Picasso was 17, the Spanish-American War exploded. Spain's quick defeat, which included the loss of her colonies, plunged the nation into self-examination. Although this would rejuvenate the arts, it was felt as a deep humiliation.

Picasso's sense of self was always complicated. He called himself a Catalonian since, from 1895-1904, he lived in Barcelona. But he was born in the southern city of Málaga. That's why his full name – Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno Crispín Crispiniano María de los Remedios de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz Picasso – retails many ties to relatives and saints. Until the age of twenty, Pablo often changed his name. He signed work as "Ruiz Blasco", "P. Ruiz Picasso", "Picas", "Picaz" or even, sometimes, "Paulo Picasso". Cartoons he published simply as "Ruiz".[1]

Málaga was where Picasso first saw a bullfight, learned to smoke from gypsies and started painting in oils. There, he also copied caricatures for hours. But by the time he was eleven, his family had moved north. They settled in the Galician port of La Coruña, where many of their neighbors spoke another language: gallego.

In La Coruña, Pablo emerged as a prodigy. Says biographer John Richardson, "[Here] his work came into its own, not just his drawing but his painting… The fact that the artist was a boy of thirteen is irrelevant." Such stunning work soon gave rise to expectations. The boy's family, said Picasso's friend Jaume Sabartés, simply assumed he deserved mainstream fame. During the next dozen years, almost everyone else agreed.

Yet Picasso's sketchbooks reveal different aims and, from the start, he filled them with cartooning. As Adam Gopnik noted in 1983, "The likenesses that crowd Picasso's notebooks from 1897 to 1905 are at odds with his finished portraits of the same period in a very striking way.… and it is the notebooks, with their crowded pages of caricature heads, that have the qualities of the mature portraits… rather than the finished canvases of the period."

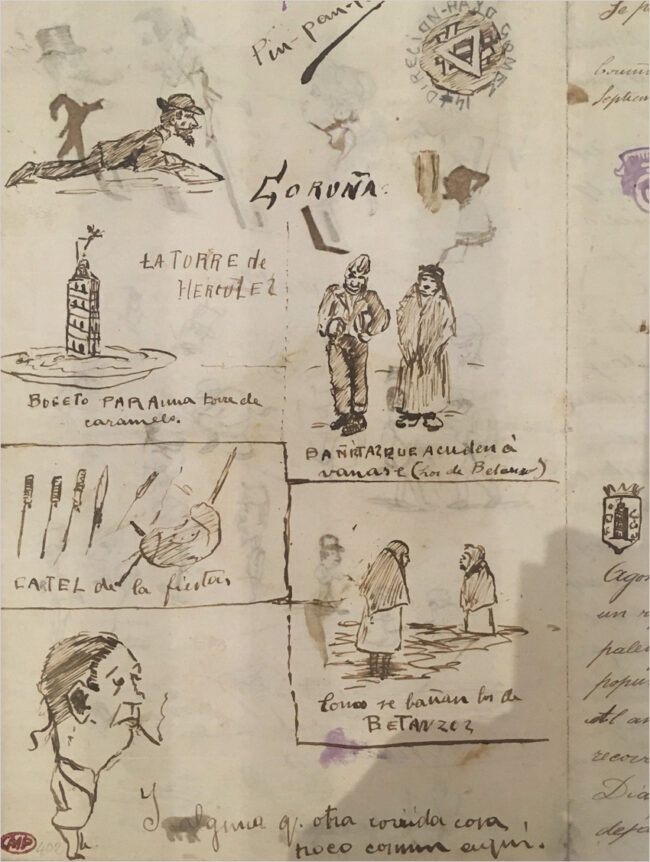

Young Pablo's father taught art and he attended class. But what the pair really agreed on was their reading, especially a weekly arts journal called Blanco y Negro ("Black and White"). By 12, Pablo had created its competition: a stationary-size zine he called Asul y Blanco ("Blue and White"). He soon diversified with a second "title", La Coruña, then a third, Torre de Hercules ("The Tower of Hercules").

Picasso gave these tiny pamphlets ads, news, public notices and comic vignettes. His brusque sketches in them depict local "types", illustrate the weather and relay events. Already, the tone of his writing is satirical: by turns ironic, caustic, funny – and surreal.

The little zines, says expert Anne Baldassari, signal what became a lifelong obsession with print. "Everything [in them] is invested with the feeling of a synthesis between the humorous drawings and the fragmented texts… Like the illustrated magazines then in their heyday, the juxtaposition of text and image, titles, headings, articles, cartoons and captions was organized to create that specific object, the newspaper."

Were there other models for Pablo's "publications"? At this point, nascent Spanish comics or historietas were mostly concerned with fables and parables. But caricature was just as popular (and as adult) as in print-crazed France. In fact, says historian Xosé Antón Castro, "[Spanish] caricature was rarely so strong and widespread as in… the context of Picasso's childhood."

Its history had long been belligerent. Spain's first satirical publications had slim circulations and their lives were ephemeral. Early pamphlets like El Zurriago ("The Whip", 1821) also had no images. But, by the 1830s, publications with names such as El Matamoscas ("The Flykiller"), El Martillo ("The Hammer") and Fray Gerundio ("Friar Gerund") had started to use decorative drawings. Inspired by the likes of La Caricature in France, satirical bonds soon flourished between their art and the text.

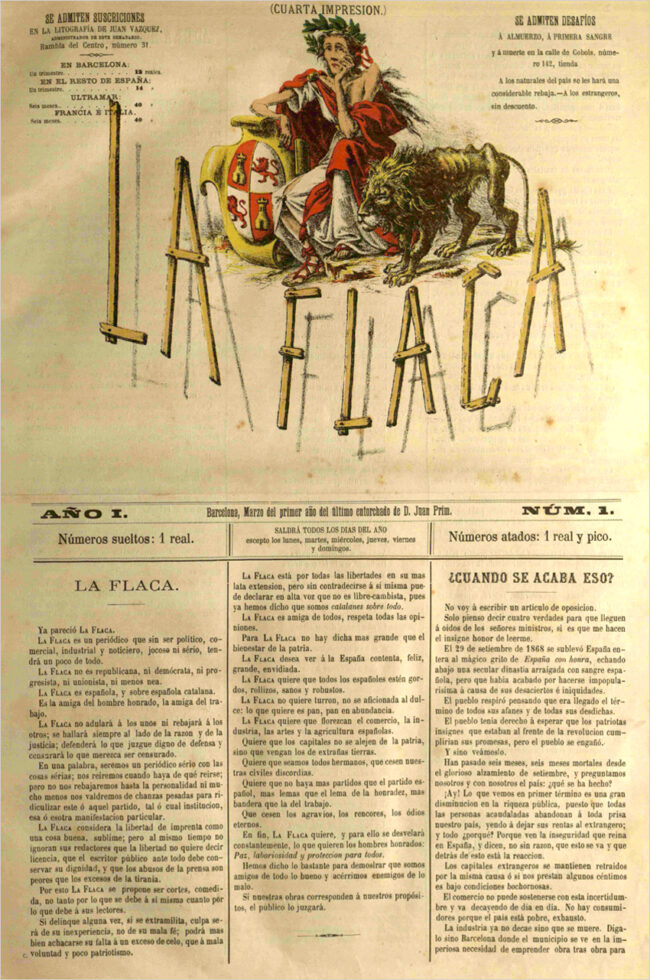

During the 1870s, Spain was briefly a republic. This was a short interlude and, when the monarchy returned, it endured until the 1930s. Yet from 1868 to 1874, the Sexenio Démocratico or "Six Democratic Years", Spanish satire blossomed. Although much of this action emanated from Madrid, there were trailblazing journals such as Córdoba's El Cencerro ("The Cowbell", but that bell of the cow who leading the herd). El Cencerro debuted in 1861, but was suspended after just five issues. It resurfaced eight years later, as "The Official Organ of Defamers".

Other pioneers included Barcelona's La Flaca ("The Skinny Girl") and Madrid's Gil Blas. Both of the latter were notable for their double-page caricatures printed in full-colour. By the time of Picasso's birth, not only were such "defamers" long-established. They also included Catalan-language publications such as La Campana de Gràcia ("The Bell of Grace", 1870-1934) and the biting La Esquella de la Torratxa ("The Bell of the Watchtower", 1872-1939). First in Barcelona, then in Paris, Picasso became close to many of their contributors.

Until his teens, however, he mostly saw cartooning through the journals Don Pepito, El Duende and El Petardo ("The Firecracker"). Along with Blanco y Negro, these inspired his homemade efforts. Yet all cartoons held a certain primacy for him, simply because they were not academic art. That was the universe his father and family revered, the world for which he was officially destined. Cartooning was a private pleasure but it was closely tied to his school's detention cell. Here, in an empty room furnished with a single bench, Picasso spent much time alone. Fifty years later, his memory of it remained sharp: "I was locked in that calaboose so frequently, hour after hour … that I learned to draw there more than anywhere else."

Spain's humorous publications tended to differ by region. The popular Madrid Cómico, for example, spawned versions including Santander Cómico in 1885, Granada Cómica in 1887; Sevilla Cómica in 1888 and, in 1889, both Valencia Cómica and Barcelona Cómica. Eventually there was also La Coruña Cómica, but it arrived years after Picasso left. By 1895, his family had moved again, this time to Barcelona.

There a bar called Els Quatre Gats changed Picasso's life.

Literally, Els Quatre Gats means "four cats", but the phrase was also Catalan slang for "just a few". It was the name of an avant-garde tavern, a café-cabaret started by four locals. Three of them had shared rooms during time in Paris and their establishment was modeled on Le Chat Noir. Both the Quatre Gats' proprietors and regulars saw themselves – rather than figures like Antonin Gaudí – as the leading lights of Catalan modernismo. They were young poets, painters, anarchists and satirists, who took part in readings, expositions and puppet shows. They also produced flyers, posters and magazines.

The artists Pablo met there were so numerous, says John Richardson, that they "tend to blur… [yet] each in his different way was an indispensable source of that admiration, support and stimulus that fueled the early stages of Picasso's rocket-like ascent." Some died young, of illness or war; others became his lifelong friends. In 1900, Els Quatre Gats held Picasso's first exhibition, comprised of over one hundred portraits and caricatures.

Until the Spanish Civil War, ties between Paris and Barcelona flourished. Since the 1830s, the French had doted on what they termed hispagnolisme: Spanish-themed art, books, music and theatre. So, whether they worked with poetry or cartoons, Spanish artists were welcome in the City of Light. Both Picasso's sketchbooks and his comics collection illustrate the era's web of urbane connections.

Of the protagonists in their fading pages, few are now remembered outside of Spain. The great exception is Carles Casegemas, immortalized by Picasso's art after his suicide. Casagemas, who was twenty when he died, deeply loved cartoons. He had studied Caran d'Ache and, like his studio-mate Pablo, worshipped Theodore Steinlen.

But more influential was the artist-caricaturist Isidre Nonell (Isidre Nonell i Monturiol, 1872-1911). Nine years Picasso's senior, Nonell scorned respectability; what he pursued were those dark subjects favored by Goya and Daumier. (The year after Pablo arrived in Barcelona, Nonell scandalized the whole city with his portraits of "cretins".) Nonell focused Pablo's eye on those streets around him, filled with prostitutes and mutilated war veterans.

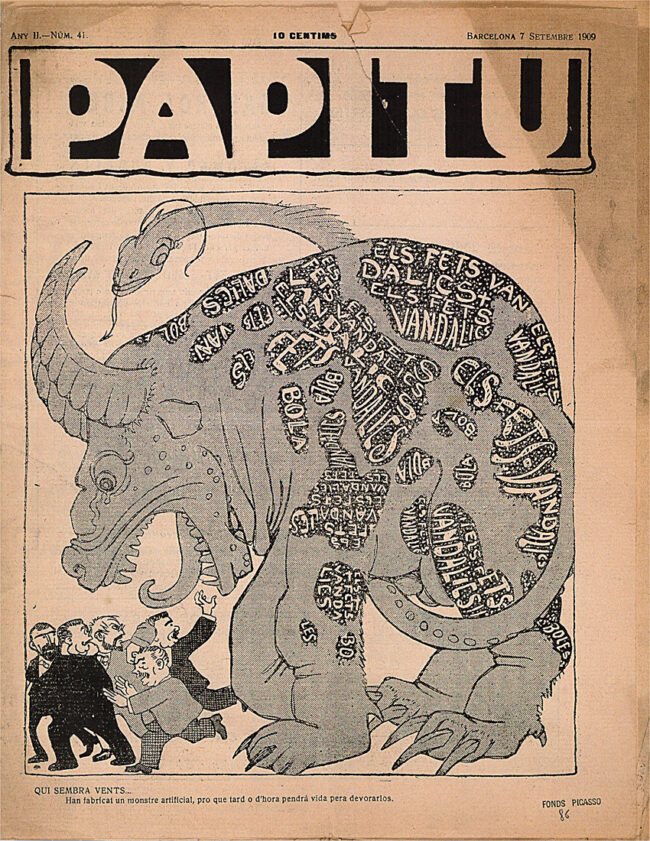

If the art at Els Quatre Gats was often derivative, it was not insular. Says historian (and cartoonist) Jaume Capdevila: "While journals headquartered in Madrid looked backwards, the graphics of Barcelona were inspired by France and Germany. During the first quarter of the 20th century, this produced the most innovative in Iberian papers: ¡Cu-cut! (1902), Papitu (1909), Picarol (1912), La Piula (1916), Cuca-Fera (1919), L'Estevet (1921) and El Borinot (1923)."

Picasso kept issues of several, including three treasured copies of Papitu. By the time Papitu appeared, he was long settled in Paris. But many of his friends contributed to the journal and his pal Ramon Reventós i Bordoy was its art critic. Whether they were based in Spain or Paris, however, all these Spaniards knew Papitu meant free expression.

This was because of what happened in 1905: the notorious fets de ¡Cu-Cut! or "The ¡Cu-Cut! Incident".

Papitu was created by "Apa", the Catalan cartoonist Feliu Elias i Brancons. Under the by-line "Joan Sacs", Elias also wrote about art. During two stints of exile in Paris, he cartooned Picasso and wrote about Cubism. But his career had begun in 1902 at the Barcelona weekly ¡Cu-Cut!. This satirical paper, published in Catalan, was enormously popular. Inspired by Paris' L'Assiette au beurre ("Bread and Butter") and Munich's Simplicissimus, ¡Cu-Cut! was read from bars to barbershops and bakeries. It proudly claimed Catalan humor to be "smarter and sharper".

On November 23, 1905, ¡Cu-Cut! ran a small cartoon by Joan Junceda (Joan García i Supervia). While hailing an electoral win, it mocked the national army. Junceda's references, although oblique, perfectly clear – especially with regard to 1898's loss of the war. When his cartoon was censored, ¡Cu-Cut! was re-printed without it. But two days later, three hundred soldiers appeared at the paper's office. They beat up fifty people, wounding some with sabres, tossed equipment into the street and set the building on fire.

The fets de ¡Cu-Cut! became a political crisis and Barcelona ended up under martial law. Further press repression also followed, in the form of a Ley de Jurisdicciones ("Law of Jurisdictions"). This forbade all criticism of "Spain or her symbols" and it remained in place until 1931. Over the next quarter-century, this law effectively strangled any critique of the army. The ¡Cu-Cut! affair divided the country, paving the way for a military coup in 1923.

Papitu was a homage, launched on the fets' third anniversary. Picasso knew Feliu Elias. But he was familiar with the work of all Spain's star cartoonists, men such as Apel·les Mestres (1854-1936), Ramón Cilla y Perez (1859-1937), Eduardo "Mecáchis" Sáenz-Hermúa (1859-1898) and Joaquín Xaudaró y Echau (1872-1933). Picasso's youthful sketchbooks have drawings in all their styles. He was born eight years after Spain's first "comic strip" – an El Mundo Cómico centerfold from 1873, which was entitled Por un coracero ("Because of a Cigar"). But its linked, captioned vignettes were drawn by Barcelona's Josep Lluís Pellicer i Fenyé. Pellicer's artist nephews, Joan and Julio, were Pablo's friends.

Often, Picasso's links to Spanish cartooning are intricate. In May of 1899, for example, in his favorite Blanco y Negro, Joaquín Xaudaró parodied one of his paintings.[2] Two years before, this same Xaudaró had founded a publication called The Monigoty.[3] Named with a pseudo-synonym for "puppet" or "dummy" (monigote), the weekly lasted just four months. But every issue ran pages of cartoons and strip comics. The Monigoty solidified that vehicle Pellicer began in El Mundo Cómico.

Between 1900 and 1904, Picasso made three separate trips to Paris. For any ambitious Spanish artist, such a pilgrimage was imperative. Spanish cartoonists might also work for French titles and some, like Francisco Ortego y Vereda (1831-1881), ended up changing countries. Ortego lived in Paris from 1871, where he became known as "the Spanish Gavarni". His deaf-mute countryman, Daniel Perea y Fernández de Rojas (1836-1909) was dubbed "Madrid's Jules Chéret" – despite the fact his specialty was not cancan girls but bullfights. Drawings by both appeared in Madrid's Gil Blas, a publication followed by Picasso's father. In a portrait of his parent painted after it closed, Pablo shows a copy of Gil Blas in his jacket.

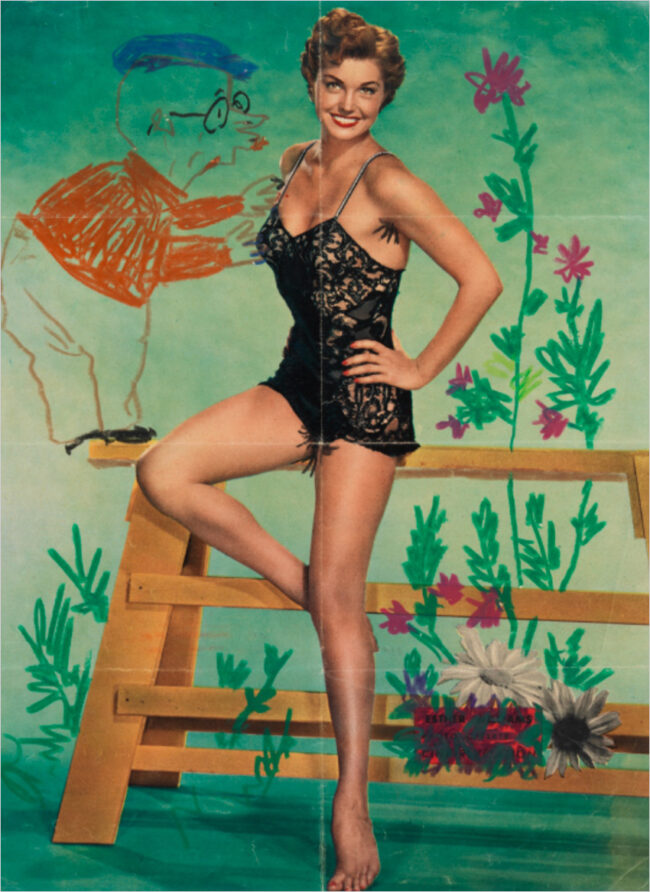

In Paris, older expats often helped the struggling Pablo. Cartoonists "Gosé" and "Sancha" (Francisco Xavier Gosé i Ribera, 1876-1915 and Francisco Sancha y Lengo, 1874-1936), for instance, worked for L'Assiette au Beurre ("The Pork Barrel"). In 1901, the publication launched an adjunct called Le Frou-Frou: journal du high-life. Through one (or both) of these countrymen, "Ruiz" received comic commissions from it.

Graphic satire was desirable, well-paid work. But Picasso's French was too minimal to translate his wit. Frou-Frou settled for caricatures of well-known dancers. Even these required the help of another Spaniard – the Catalan Josep Oller i Roca, who managed Le Moulin Rouge. After his first double-page spread, for eighteen months Le Frou Frou declined Ruiz. Between 1901 and 1903, he only placed one vignette in Gil Blas illustré and three illustrations in Le Journal pour tous.

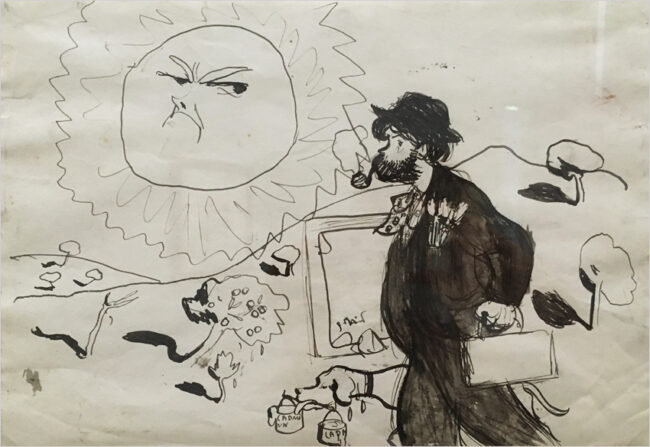

When it came to caricature, however, Pablo's great epiphany pre-dated Paris. During 1897, he spent nine months at art school in Madrid. There, in the Museo del Prado, he ran across some century-old drawings by Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. Goya was the Spanish king's personal painter. But he was also an afrancescado – a Francophile. So when Revolution erupted in neighboring France, the artist panicked. To make things worse, he then fell deathly ill. Goya's sufferings lasted a year and, when he finally recovered, the painter found he was totally deaf.

Madrid Album of 1796-1797; later used for Capricho 13), by Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes; Museo de Prado

While he recuperated, Goya started drawing. Some of these clandestine sketches fueled Los Caprichos, eighty etchings he published in 1799. Los Caprichos ("Capers" or "Follies") were totally unprecedented. Firstly, they were engravings – hardly seen as a prestigious form. Secondly, their ruthless satire targeted his own peers. But what grabbed Picasso were the drawings which had led to them, more personal efforts that Goya never censored. Done in brush, pen, India ink and chalk, these scenes are filled by half-human, half-animal figures. It's a spooky, venal, supernatural world, in which old women light their fires using naked infants.

Such visions mark the birth of a different Goya, one we now acknowledge as a modern master. But when Picasso first saw them at 16, he knew little about where they came from. He didn't know they were galvanized by two great satirists.

Goya's long convalescence took place in the homes of friends, one of whom was banker Sebastian Martínez y Perez. Martínez owned more than three hundred paintings. But he was also Spain's biggest print purchaser – who adored both William Hogarth and James Gillray.

These Anglophilic tastes were shared by Goya's second host, the writer and dramatist Leandro Fernández de Moratín. Moratín had just returned from a trip to England, where he was stunned by satire's extremity. "Everything," he wrote in his diary, "is a fit subject for these plates …caricature often supplements or even exceeds criticism or the bitterest satire. I have seen the manners of every country, its customs and even its virtues ridiculed in these sheets… They show the king of England shitting into a chamber-pot while holding a privy council with his ministers portrayed as wolves, weasels, foxes and birds of prey."

Their two collections changed Francisco de Goya. The Hogarth prints, some of them etched and engraved by the artist, were technically peerless. But Gillray's work was the real revelation. After 1792, with the French Revolution's dive into Terror, his frenzied comedy attained a kind of boiling point. While he continued to skewer bourgeois art for laughs, Gillray was consumed by new, Romantic compulsions. The results still seem phantasmagorical, like the exposure of a barely-under-control subconscious. Gillray was friends with the painter Henry Fuseli, whose famous Night Mare had shocked all of Europe. What he wanted to create, Gillray told Fuseli, was the satirical equivalent of that power.[4]

Goya sensed all this the minute he saw Gillray's work – and it was what Picasso felt in the Goya drawings. One of them – entitled Caricature Alegre or "Merry Caricature" – features three gluttonous monks. In order to publish the scene, Goya had to tone it down, making three versions. The actual Capricho, number 13, reduces its brutality to a menacing gloom. But the "Merry Caricature" itself stuck with Picasso, especially the flat planes and mask-like character of its faces.

The satire Picasso loved to read echoed Goya's codes. In it, for instance, bodily deformation usually meant moral decay. Despite its Francophone ties and inspirations, too, such cartooning was very different to that practiced in France. For many French publications, whether a caricature was drawn by André Gill or Daumier, its mockery aimed to provoke more than laughs. Much French cartooning campaigned for progress and hoped for social change. Its Spanish counterparts, even when backing anarchism or a republic, seem resigned.

The same tropes of caricature appeared in both countries: big heads, phallic noses and parodic parades. But, in Spain, the realities underneath appear immovable. "The feeling we have when looking at these illustrations and reading their texts," writes Valeriano Bozal, author of La illustracion gráfica del siglo XIX en España ("The Graphic illustration of 19th Century Spain"), "is that there is no solution."

This graphic pessimism, says Bozal, was pre-existent; already, it had been around two centuries. Mythological violence and the torture of saints existed in Spanish art since the Middle Ages. But, by Goya's time, monstrous personae were invading the grandest spheres. It was then, says the historian, that mutants and aberrations "escaped the confines of popular prints and started to pose for painters". Nor were they just any painters – some of them were celebrities of the Golden Age. José de Ribera offered his viewers a bearded woman, Diego Velázquez painted a mentally-ill clown and Juan Carreño de Miranda unveiled a real-life, obese, six-year old girl… naked.[5]

Picasso's affinity with such grotesquerie was innate. Says Xose Antón Castro, "Many of his first doodles fall into a category of meta-irony, an attitude reinforced by his experience of Galicia's existential doubt, humor and double-sided codes… It was this that gave rise to his vocation as a caricaturist. In those books on which he drew in class and, more particularly, in the calaboose, he incubated this reflexive, caustic outlook. It would end up defining one of the most critical slants in his practice… eventually giving us Guernica."

In 1903, Els Quatre Gats closed. A year later, the sculptor Francisco Durrio offered Picasso the lease on his Paris studio. So Pablo departed Barcelona for good. His new home was part of Montmartre's Bateau Lavoir ("The Laundry Boat"): a rickety, three-floor edifice built against a hill. Although the building boasted only a single faucet, more than thirty artists called it home. This new mix of writers, painters and eccentrics was a multinational, multilingual group.

Picasso lived here five years, much of it in genuine poverty. Yet he always recalled the era as glorious, filled with camaraderie and creative progress. It was in the Bateau Lavoir that, after only a year, he began painting his new acquaintance Gertrude Stein. A supersized, ambitious, well-off American, Stein and her brother were buying Picasso's art. They befriended the painter and his friends, one of whom was now the poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Apollinaire (initially Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary Kostrowicki) was skeptical about the Steins – especially when it came to Gertrude's robes and sandals. Often," he complained, "if these millionaires decide to relax at a café … the waiters refuse to serve them, sniffing that their establishment's drinks are 'too expensive for people in sandals'."

But Pablo made friends with Stein right away. Since neither he nor she could really speak French, they communicated in a personal pidgin-speak. Soon Stein introduced the artist to American comics, passing on "the Sundays" from her imported papers. She made Picasso and Fernande fans of Little Jimmy, Little Nemo and The Katzenjammer Kids.

Picasso's Portrait of Gertrude Stein makes a critical break. To know how Gertrude Stein looked, there is a Felix Vallotton portrait painted just a year later. But to envision her as a force and a personality (not to mention a self-promoter who endured ninety sittings), we need Picasso's version. While he was creating it, Paris held a retrospective of the painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This is partly why, in transmitting Stein's presence and privilege, Pablo stole from Ingres' Monsieur Bertin – one of the greatest portraits ever made. His sitter's mask-like face, as classical as it is cartoonish, also makes a nod to Ingres' Tu Marcellus Eris.

But Stein's painted visage is so graphically minimal that it also calls to mind someone else: Rudolph Dirk's comic character Mama Katzenjammer. [6] Mama too was an expat, with a similar heft, vernacular and chignon.

There are countless theories about the portrait's real recipe. But Gertrude Stein embodies that moment when, as Adam Gopnik says, "the principles of caricature first entered Picasso's high portraiture". It also heralds a newly self-assured Picasso – whose Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, painted a year later, jumpstarted Cubism. If caricature's role in this moment is subtle, it is nevertheless crucial. What Picasso took from it was utter simplicity and the use of minimal line for maximum insight. To arrive at this point, he labored to acquire the tools of Hogarth and Daumier – what Ernst Gombrich calls "a mastery of variety and a deep knowledge of character".

Art histories root Cubism in earlier work, experiments by Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. Picasso's interest in these intensified when he encountered African masks and Iberian sculpture. But nothing could have predicted Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The painting, which stars five enormous prostitutes, shattered all codes of how art was meant to "see".

It hangs today in New York's MOMA, who describe it thusly: "The women emerge from brown, white, and blue curtains that look like shattered glass, their bodies thrust forward toward the viewer by the scene’s lack of depth. Their eyes – enormous and almond-shaped, and inspired by African and Iberian carvings – are fixed daringly on the viewer. Near their feet sits a small arrangement of fruit, with a scythe-like sliver of melon set behind a bunch of grapes, an apple, and a pear, and which, like the women’s bodies, seems too sharp to touch."

In that pear, cartooning also shows its hand. For, once Picasso was friends with Apollinaire, he caricatured his friend's Bosc-shaped head non-stop. This was more than just a joke between the two of them. It invoked French satire's most historic image: the pear-for-a-head cartoons that helped topple Louis-Philippe, the last-ever French king. Starting with a sketch made during a trial – the 1831 prosecution of cartoonist Charles Philipon – the pear morphed into a symbol of free expression. As pear prints, cartoons and graffiti spread through Europe, the fruit became surreal as well as subversive. Of its many deployers, the most well-known was Picasso's idol Daumier.

Picasso pursued his own version of this pear, from cartoons of Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi ("King Ubu") through many Cubist portraits. So it's no accident that one appears in Les Demoiselles.[7] "Works of art settle down eventually and become respectable," wrote British critic Jonathan Jones on the occasion of the work's centenary. "But, one hundred years on, Les Demoiselles is still so new, so troubling, it would be an insult to call it a masterpiece".

Perhaps not too insulting, though, when you look again at the two figures whose heads are "African". Are these strange faces simply a new of old ritual?[8] Perhaps not, since they also resemble two of the greedy monks in Goya's "Merry Caricature".

Les Demoiselles horrified all Picasso's friends. His huge, glaring, angular women were just too radical. The uproar they caused made one critic, Félix Fénéon, all the keener to see it. But, in front of the actual painting, he too hooted with laughter – then told Picasso "you should stick to caricature". Although Picasso was crushed, he was not deterred. All really good portraits, he noted, "are, in their own way, always caricatures".

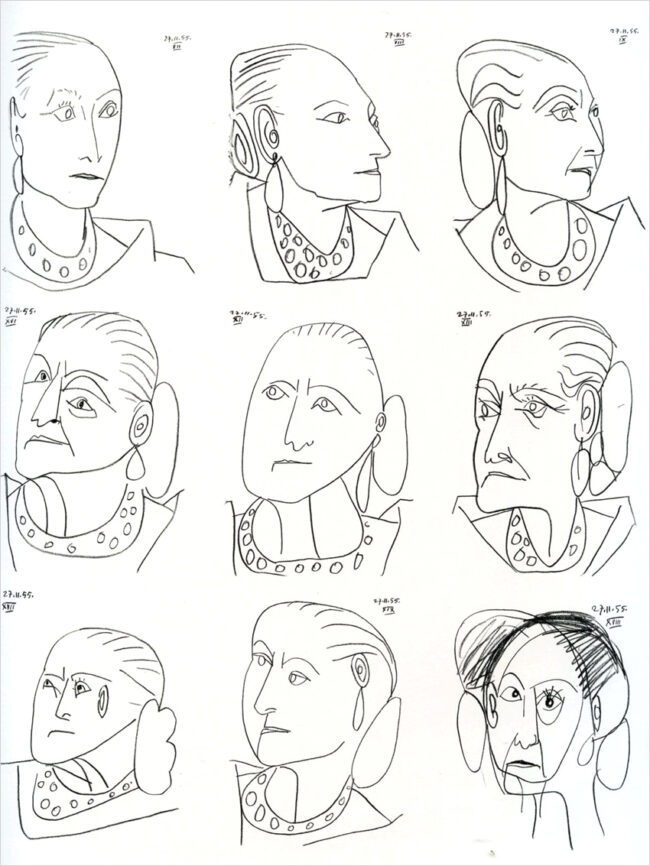

Examples like this recur throughout his whole career. In 1955, for instance, he began a portrait of cosmetics czar Helena Rubinstein. Rubinstein was feisty, a character who escaped Poland's slums to forge an empire. Her art collection was prodigious and, for over twenty years, she had begged Picasso to paint her. Finally, when she doorstepped him at home, the artist agreed.

But her sittings ended up as a group of graphic studies. In the loftiest sense, these are just caricatures. Yet they demonstrate how well Picasso knew that art and how, as with any genre, he revised it. He found in caricature, says the historian Bertrand Tillier, "a slang that, even in works of very diverse ambitions, never ceased to fascinate him". Caricature, in its turn, helped educate Picasso. It provided one of the means by which he learned how to appropriate, paraphrase and transform anything.

Part of this emancipation came through Goya, incorporating the revelation Goya got from Gillray. No hay reglas en la Pintura – In painting, there are no rules.

- The Musée Picasso is temporarily closed during quarantine but Picasso et la Bande Dessinée (Picasso and Comics) runs through January 3 and will probably be extended. Timed visits must be booked in advance; all visitors must wear masks and observe social distancing.

- Heartfelt thanks to both Johan Popelard, Curator of Graphic Collections at the Musée Picasso-Paris and Francesca Sabatini of Claudine Colin Communications. Also to Dr. Rhiannon McGlade, whose "Catalan Comics: A Cultural and Political History" (University of Wales) I highly recommend.

Of special help with this article were: the Hemeroteca Digital of the Biblioteca Nacional de España; "Picasso: From Caricature to Metamorphosis of Style", Barcelona, Museu Picasso, 2003; "Journalism, Caricature and Satirical Drawings in Early Picasso", Xosé Antón Castro Fernández, 2017; Manuel Barrero, "Orígenes de la Historieta Española, 1857-1906", ARBOR Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura; "Picasso Working on Paper", Anne Baldassari, The Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2000; "Picasso & La Presse", L'Humanité /Editions Cercle d'Art, 2000; "High and Low: Caricature, Primitivism and the Cubist Portrait", Adam Gopnik, Art Journal, The Issue of Caricature (Winter, 1983); "City of Laughter", Vic Gatrell, Atlantic Books, 2006 and "Goya's Caprichos", Frank I. Heckes , Art Journal, July 2014.