Before I tell you more about my own musical education, I think I need to give you more context about my parents and their scene, which was already going full throttle when I was born in 1944.

My father grew up poor in the Depression-era 1930s. By the time he was a teenager, he was living with his mother in Los Angeles in a theatrical boarding house. It was run by a woman everyone called Auntie Mae. He told me he knew a lot of kids who were in pictures, as some of them lived at this boarding house. And also, my cousin Gloria was in the movies, sort of. Gloria's mother was trying to make her into the next Shirley Temple, but she never really clicked in the movies, and her biggest Hollywood coup came in the 1940s when she married the lyricist Sammy Cahn.

But getting back to my father: He was already music crazy and a big swing fan. One of two big musical memories he often recounted was seeing the Duke Ellington Orchestra in a vaudeville house. He said when the band went into Mood Indigo out of a medley, the house shined blue lights on them. It made a lasting impression on him; later, his 78 collection had a lot of Ellington in it. Not exactly "Moldy Fig," but here my parents seemed to stretch a point, and those Ellington sides were my to be my later segue into actually appreciating jazz. The other seminal experience he told me about occurred in the late '30s, when he and a friend slipped into a hotel where Benny Goodman's band was playing. They somehow managed to get into the room where the played played one afternoon, hid under some tables and listened to the band's rehearsal. Imagine!

My parents actually met around 1942 — wartime. My mother was what was called an airplane spotter in a defense plant. It had something to do with spotting enemy planes in the sky (not spotting paint on the planes). My father, like most young men at the time, was in the army. But at that stage he was not being trained for combat. Because of his drawing talent, he had a job making realistic drawings of airplane parts from blue prints in an army plant somewhere in Los Angeles.

I guess where my mother and father each worked was either in the same place or close by each other because they met in a carpool. There were wartime gas shortages so, I'm told, there were lots of carpools. Anyway, my mother was already a jazz fan, too. And it was their mutual interest in jazz music that soon had them going out on dates together. My father was a huge Louis Armstrong fan (not a hard thing to be, if you know much about music).

My mother, I was told, was a big fan of another jazz trumpeter named Muggsy Spanier. He's not the household name that Armstrong still is, but he was great. He was a white guy and kind of funny looking, which must be where the name Muggsy came from. At that time he was making some fairly well-celebrated New Orleans style jazz records that fell pretty safely into the moldy fig category, but his bread and butter gig for years had been playing with the Ted Lewis band. Now, Lewis himself didn't really play jazz. He had a hambone vaudeville way of singing, and wearing a crushed top hat was a theatrical shtick of his. His own clarinet playing was not an authentic jazz style, though I've come to kind of like it. Funnily, when you hear Lewis's thin playing on one of his records it's still no guarantee that you are actually hearing him. Jimmy Dorsey, who sometimes played on Lewis record dates, did a great Ted Lewis imitation. In fact all kinds of jazz greats turn up on his sides. And through nearly all of those sides there's Muggsy Spanier playing some of the most amazing trumpet — mostly jazz, sometimes not, nearly always great.

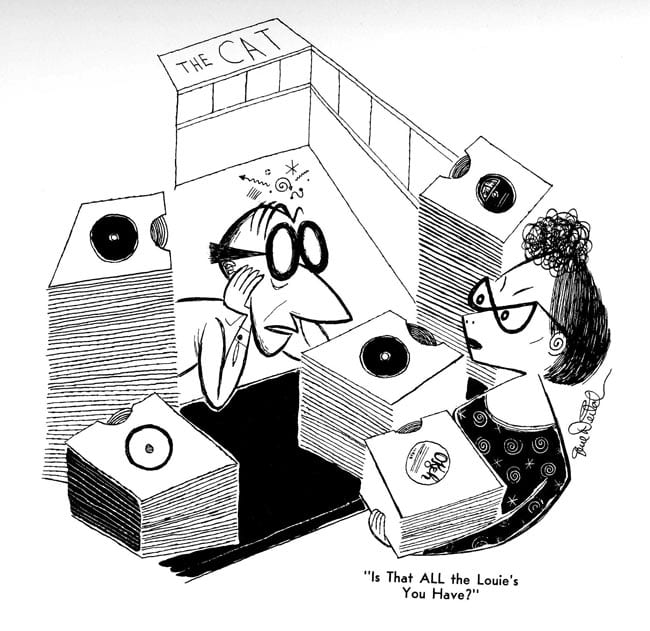

And so they were married. My father got his release from the army the day after I was born and did his best to set himself up in Los Angeles as a commercial artist. I guess at first it was whatever he could pick up freelance, but he eventually landed a gig with CBS radio. It was slim pickin's. He was pulling about $40 a week from all this. On the side he started working for a moldy fig-oriented record collecting magazine called The Record Changer for no money whatsoever. Through every other job he had in the ensuing years, he drew nearly every cover for that mag, and also did a one panel cartoon in every issue called "The Cat" (as in hep cat, not the critter). This character was a record collecting jazz maniac. He looked something like my father and, to a certain extent, was based on him (though somewhat exaggerated for comic effect). This went on from late 1945 to about 1950.

Seeing my father working on these things must be just about my earliest memories of the art game and although he got no money for this gig, it was his entrée into the animation business. You see, a lot of the animation guys were also into jazz, like the Firehouse Five guys mentioned last week. And some guys, mostly left-leaning refuges from Walt Disney and Warner Brothers cartoons, had formed a cutting edge, modern art-oriented studio called UPA. I think it initially stood for United Productions of America, but it was always called UPA. Well, these guys saw my Father's stuff in The Record Changer. One thing led to another and soon my Father was working at UPA as an assistant layout man under the wing of the legendary John Hubley.

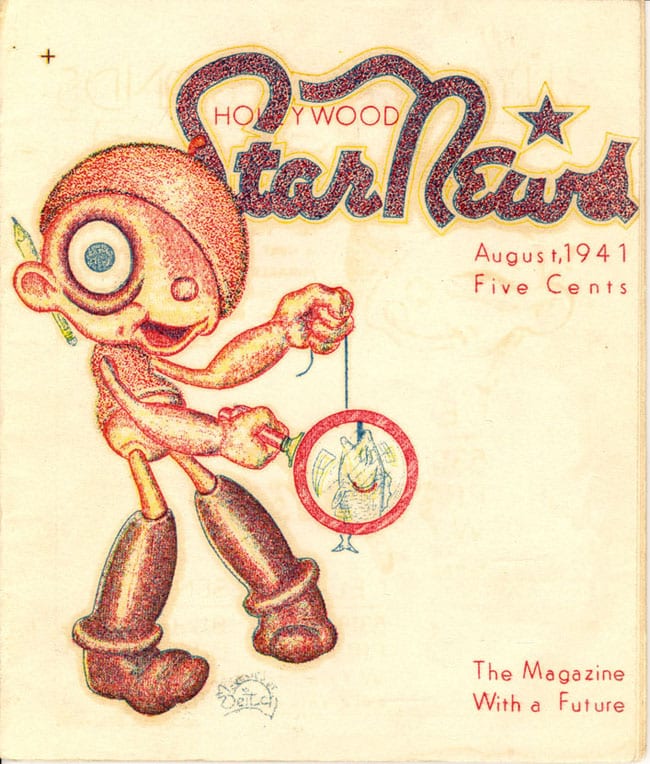

My father's interest in art had been long standing. He'd been a huge fan of Mickey Mouse growing up. By the time he was a teenager, he was putting out an amazing magazine called The Hollywood Star News. When I say amazing, I'm not kidding. It was produced on a hand cranked mimeograph machine. What's that? Well, before photocopiers people could make cheap copies by typing onto wax sheets. Then you'd put the typed sheet onto a rotary mechanism filled with ink. Turn the barrel one revolution as you feed a piece of paper under it and you'd have a copy, in ink, of what was on the typed wax sheet. Keep turning as you feed more paper under the barrel and you'd get more copies. You could do at least quite a few hundred copies this way. You could also draw on the stencils and have crude illustrations, or not so crude in my father's case. My old man, genius that he is, came up with a way to do four-color illustrations with good registration in The Hollywood Star News. Those mags, produced in 1940 and '41, looked just great.

In every issue my father would visit one of the Hollywood cartoon studios (the snappy looking issues of The Hollywood Star News made a great calling card for getting him through the front door). My father visited them all this way: Walter Lantz, Harmon and Ising at MGM, Warners, up to and including the great Walt Disney Studios where Walt personally gave him the grand tour. He also signed a program book for the studio's then latest release, Fantasia. My father still has it.

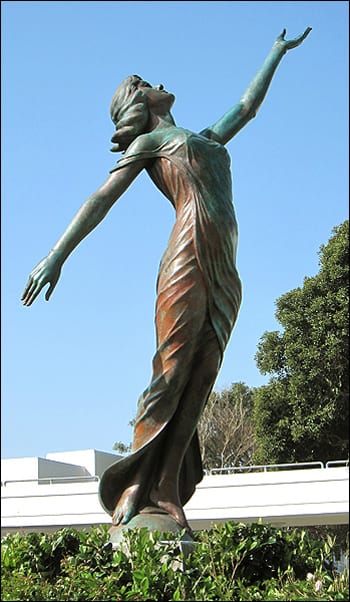

But actually his contact with animation goes back even earlier. L.A. is a movie town. My father went to Venice High, an L.A.-area school. I guess Myrna Loy had gone there earlier, because for years a discrete nude statue of her stood out in front of Venice High. I think it's gone now, but it stayed there quite a while. Well, Venice High was such a progressive school that they actually had an elective course in animation that my father took in 1937. There, at age 13, he made an animated cartoon called Paul Parrot Goes To Mars. I don't think it was actually shot onto film.

By time I was emerging into consciousness, Mom, Dad and me were living in a rented bungalow on Westbourne Drive just off La Cienega Boulevard in downtown L.A. Though poor as church mice, they were pretty social. Every Friday night they had open house parties called "record sessions" for like-minded jazz fans and musicians. There was an upright piano in the bungalow that some earlier renter must have left behind. My father made a lot of acetate disks of a jazz pianist named Johnny Witwer who was more or less a regular at these parties. Years later my mother told me that one night someone brought trumpeter Louis Prima over. Today he is mostly remembered as kind of a Las Vegas show biz personality, but he came from New Orleans and in, the early days, he was a rather good jazz musician. He was apparently roaring drunk the night he came to our house, though, because the main thing he did that night was to try and put the make on my mother.

Backing up a little, my father began as a swing band fan, but then converted to New Orleans jazz. See, there was a jazz-oriented shop called The Ray Avery Record Store and my father must already have been frequenting it while he was still in high school. One day he was in there listening to a record by Bob Crosby's Bobcats. This was a small band within Bob Crosby's larger swing band. Bob was Bing Crosby's younger brother and, some say Bing may have had something to do with getting Bob the gig fronting that band. You see, the Crosby band was not really run by Bob Crosby. It was what was known then as a co-operative band. The members of the band ran it among themselves. There were a number of bands like this. The Jimmy Lunceford band was another co-op band. Twenty-one-year-old Ella Fitzgerald fronted the Chic Webb band, after Chick died, as Ella Fitzgerald And Her Famous Orchestra.

The Crosby band was made up of mostly members of the disbanded Ben Pollack band and had some really great players in it. Bob Haggard on string bass and Ray Badouc on drums was its great rhythm section; Bob Zurke played solid piano and Irving Fazola clarinet. The band's first choice for a front had been Jack Teagarden, but he was still working out his 10 year contract with Paul Whiteman. And so the gig went to Bob Crosby. If they couldn't get Bing at least they had a Crosby, and that magic Crosby name right out front. Actually Bing later did some sides with them. "You Must have Been a Beautiful Baby" is a particular stand out. Let me also explain this small band within a bigger band phenomenon. Just about all the big bands had them, and this may even have even been a root cause of the later New Orleans revival. Benny Goodman had the Benny Goodman quartet. Tommy Dorsey had the Clam Bake Seven. Artie Shaw had The Gramercy Five and Bob Crosby had The Bobcats.

So, one day there’s my father in the Ray Avery Record Store listening to a Bobcats side. "Man", he said, "that's the real jazz." The woman behind the counter looked at him kind of funny, took the Bobcats record off the turntable and went foraging for another record. A moment later she put on a 1923 Gennett record by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band and said to my father, "No, that's the real jazz." Thus the dye was cast.

My father still frequented the Ray Avery Record store when I was little and I remember spending many Saturday afternoons there while my father talked, bought and traded sides. So I guess you could say I came by my interest in all this honestly enough.

Jazz wasn't the only part of my family's musical diet. Folk music which was another big musical genre. In a way you could say this included jazz and blues, but it went beyond that because my parents were following folk music as it was being performed by contemporary performers in Los Angeles. I'm told Pete Seeger used to sing me lullabies when I was still in my cradle. I don't remember that, but I can't remember a time when I didn't know him. In those days he sang with a group that was led by Woody Guthrie called The Almanac Singers. My parents also knew Guthrie, though I never met him that I can recall. The Almanac Singers sang union organizing songs. One was called the Union Maid, done to the tune of the old song about the Indian maiden, Red Wing. This was part of a larger left wing political scene that my folks were involved in, although I didn't really know much about it at the time. A lot of the music, even the jazz, was over my head in those days. I heard it because they played it all the time but I wasn't really taking all that much of it in, just yet. There was a lot of Woody Guthrie stuff I grew to love later on. The great key piece of this material was a series of records made by Alan Lomax in 1940. I already mentioned Alan Lomax in conjunction with Jelly Roll Morton, but I think he's worth taking a little time to talk about.

Alan Lomax came out of the American South and was the son of the American folklore expert, John Lomax. I'm not sure how far back John Lomax goes, but I think we had books by him from the 1920s. One of them, if I recall this right, had to do with tracing the origins of the famous folk song about John Henry (you know, the steel driving man). I believe John Lomax also discovered the famous black blues/folk singer, and 12 string guitar wizard Leadbelly in a Southern prison back in the 1930s. Alan picked up this work and his great innovation seems to have been getting records into the mix, although John may have made the earliest ones of Leadbelly. But in 1937, under the auspices of the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax made a series of records of the famous jazz man Jelly Roll Morton. It was done on crude equipment with acetate recording disks. Though these records were made in '37, I don't think they were actually issued until the post war '40s when they came out as a pricey set of 78 RPM record albums. They must have cost a pretty penny, but my folks managed to find the money and get them. I really think they must have caused some kind of a sensation at the time. How could they not have? There had never been anything like it before that I knew of.

I’ll do my best to lay it out for you. Jelly Roll Morton, a light skinned creole black man, had been a pretty big deal once upon a time. Unlike a lot of black Jazz performers, his record career was not just confined to so-called race records. In the 1920s he had a contract with Victor Records. His sides, mostly recorded as Jelly Roll Morton and his Red Hot Peppers, were well recorded, often big sellers, and are still considered classics of their kind. But by 1937, like so many others in those Depression days, Jelly Roll had fallen on hard times. Alan Lomax came upon him playing piano in a run down Washington DC night club. Now, Jelly Roll Morton was kind of a character and you couldn't take everything he said at face value. For instance, he claimed to have flat out invented jazz. In fact he gained a certain amount of public attention shortly before Lomax found him by writing a letter to Robert Ripley (of Believe It Or Not fame) making that claim. Well, he didn't invent jazz -- no single person did. But he did have a lot to do with its rise as a popular American genre. He was born in New Orleans and was in on a lot of musical history having to do with jazz. Alan Lomax was smart enough to realize the potential in getting this man's story down. And somewhere, over a period of weeks or months, in a government building in Washington DC, he did just that. The 78 RPM post-war albums of this must have covered 10 or more hours of playing time. They were edited a bit because Morton was drinking some of the time, and since jazz essentially came out of New Orleans whorehouses, some of this material was a little bit on the blue side. But that was small potatoes. These records were solid gold. He spoke of the emergence of jazz from way back before records. For instance he spoke extendedly and movingly about the legendary but unrecorded jazz trumpet player Buddy Bolden who went insane in 1907. It's a good thing Lomax got to Morton when he did, because Morton died of a heart attack in 1941. The more I think about it, this may indeed have been the real start of the New Orleans (moldy fig) jazz revival. Because of the bounce Morton got from the attention paid to those Lomax records he began to record again. He didn't get anything like the attention he got from his '20s Victor sides but they are fine records. Besides Morton's new jazz band sessions, there also emerged a nice 78 album that was modeled on the Lomax oral history, only in better sound, called New Orleans Memories. I have that album and it is a beauty. Among the tunes he does, with little talking intros (just like the Library of Congress sides), were, "Mamie's Blues", "Whinin' Boy Blues", and "I Thought I heard Buddy Bolden Say". They are touchingly beautiful.

So, Alan Lomax was on a roll. In 1940. he made a similar series of records with Oklahoma folk singer Woody Guthrie which were just as influential in their own way as the Morton records had been. Again, I was really too young to appreciate this stuff at the time, but I caught up with them later on. Here was another fabulous American original; a great singer and story teller. He makes a great case for the state of Oklahoma too, lavishly praising fellow Oklahoman Will Rogers while sort of pole axing another Oklahoma folk music pioneer, Jimmy Rogers, whose singing style resembles Guthrie's to some extent. Anyway the Guthrie sides, among other things, describe the great Oklahoma dust bowl that caused the migration of so many farm workers from Oklahoma to California. In fact, that is the incident he describes concerning Jimmy Rogers. It was not so much a personal attack as an attack on Jimmy Rogers' record of the late '20s, "California Blues". Guthrie describes the impact that record had on him and his fellow Oklahomans, how it influenced him and others to make that migration to the promised land of California when the dust bowl hit and what a bust that turned out to be. Of course Jimmy Rogers was dead by then, but lingering bitterness about that record seemed to linger on. And this seemed to be where the politicization of folk music began to take root, although politics seem to always be around. In fact, another Oklahoma singer, future cowboy star Gene Autry, had already recorded "The Death Of Mother Jones" all the way back in 1930.

My folks were already buying me lots of kiddie records. Genie The Magic Record from 1946, a double sided 12 incher by Peter Lind Hayes, son of the famous vaudeville singer, Grace Hayes, was one I held onto for years. But a lot of these records had a folk music lick to them as well. Many were by a folk singer named Tom Glazer and many were even by Pete Seeger. Some, I suppose, had a left-wing feeling about them, but more than that they were fascinating pieces of real Americana. I would say that the most fabulous of these records was a 78 RPM album by Merle Travis. I guess you could say he was a country performer but he seemed to transcend that. He was also a guitar virtuoso and he came out of the Kentucky coal mining country. This album was billed as a kid's record but was barely that, even though some of the sides did have spoken introductions where he addressed his listeners as boys and girls. Some of the tunes include "Ground Hog", where he did talking effects with his guitar; there was the folk song "Barbara Allen", which he introduced as "old as the hills." It is touchingly beautiful in its simplicity and is still my hands down favorite version of that old song. Another huge favorite, for me, and I carried the disk around for years after right into early adulthood, was the song "I Am A Pilgrim", which, I think, is a negro spiritual. Also on this album was one of Travis's own compositions, "Sixteen Tons", all about Kentucky coal mining. It is the same song Tennessee Ernie Ford had his big top forty hit with a dozen or so years later. It's funny how many things like that popped up again in later years as my musical education grew and evolved. I was definitely fortunate to be well positioned to learn a lot about different kinds of music.

One side effect of my parents' music mania was that the old acetate recorder my old man had was also pressed into use to record me and my brother growing up, the same way some families made home movies. Later, sorting through my dad's discards, I even found an old record of me crying in my cradle way back in 1944, the year I was born. Acetate blanks cost money, which is a thing my folks didn't have much of in those days so a lot of those records my father used were actually discards he picked up in radio stations and later, sometimes the already-recorded-on flip sides were an added source of fascination to me. There would be things like lead ins for the old Martin Block Make Believe Ball Room show and various odd air checks of old radio shows my old man made for one reason or another.

A big change came for our family in 1949. My father decided it was high time he got a raise at UPA, and the story I heard (which may not be precisely true) was that he went to Steve Boususto, the head man at UPA, and told him that if he didn't get a raise he was going to jump out a window. And Boususto is supposed to have replied, "Well Gene, go ahead and jump." The offshoot of whatever happened is that my father went to Detroit and managed to get a job at a massive industrial film plant called Jam Handy (so named for the man who ran the place). God only knows how long it had been going, but it was the hugest movie plant I had ever seen up to that time. So we left California in 1949 and relocated to a Detroit suburb called Pleasant Ridge which incidentally was the Catholic Parish presided over by Father Coughlin, a nationally famous racist and bigot in his day, and I remember my father pointing his church out to me, which was not so very far from where we lived.

I think my folks tried to keep the Friday night record sessions going in Detroit but they gradually dwindled. The fascinating thing I was witnessing first hand, were the changes to recorded music technology. I'll write briefly about two big ones and one seemingly little one.

Change number one was LP records. I remember distinctly the first time my old man showed me one and explained to me how much more music you could get on them. This happened in Detroit in late 1949, although LPs had already been around for at least a year or two before that.

Change number two was a big one. This also happened in 1949 (a big year and it may take me a while to get out of it). My father upgraded his home recording activities that year from acetate disks to magnetic recording tape. This was huge, and really caused a major revolution throughout the entire music recording industry. Suddenly you had better easily obtainable recording fidelity and longer recording time. I can't emphasize enough what a revolutionary thing this was. And it was one of the things that helped my father make his next big home recording breakthrough. Detroit was already an emerging rhythm & blues mecca. And one performer in this genre was a young black guy named John Lee Hooker. My old man really wasn't ready to cross the divide from country blues and city blues into rhythm & blues (that eventually evolved into rock 'n roll). Nevertheless, somewhere he'd gotten wind of the fact that this man Hooker, though already a rhythm and blues performer, was an old country guy who knew plenty about the blues and could perform it well. Somehow, my old man lured John Lee Hooker over to our house several times and, and taking a page out of the Alan Lomax playbook, recorded John Lee Hooker singing and playing the old country blues on an acoustic guitar. I was too young to stay up and actually witness this but I still remember the glow in my father's eyes as he described one of these sessions to me played some of the tapes the morning after. These records are classics of their kind and are available on a CD called The Unknown John Lee Hooker. Of course Hooker was already playing electric guitar on r&b sides, many of which must have begun to come out on what was, change number three, the 45 RPM single record pioneered by RCA Victor. My father dabbled in these but they never really caught on with him. They really had more to do with the next generation of record fiends: my generation.