New York-based cartoonist and teacher Josh Bayer's aggressive, ambitious comics can, at first glance, appear to be made up on the spot. Raw Power, Rom, and his frantic contributions to his anthology Suspect Device embrace a “first thought best thought” style of writing and a decidedly nervous and energetic line that creeps off the page, like it cannot be contained. It is dense, overwhelming work.

New York-based cartoonist and teacher Josh Bayer's aggressive, ambitious comics can, at first glance, appear to be made up on the spot. Raw Power, Rom, and his frantic contributions to his anthology Suspect Device embrace a “first thought best thought” style of writing and a decidedly nervous and energetic line that creeps off the page, like it cannot be contained. It is dense, overwhelming work.

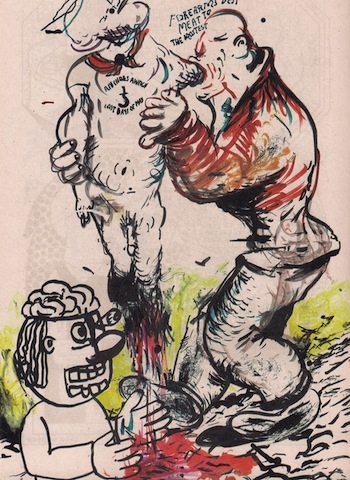

His series Raw Power, about a vigilante G. Gordon Liddy-inspired antihero who beats up punk rockers – and who is revealed to be a knucklehead cog in a major label conspiracy to make sure punk doesn't foment a revolution like rock n' roll did in the sixties – is an excellent example of a high-concept comic book conceit seen through to its logical, nutty end. And his “cover comic” Rom recreates, panel-by-panel, stories from the Marvel space-knight book from the eighties, locating the still vital energy of this work, while also shaking off its relatively square and mainstream-courting tics. It's the difference between say, the Kingsmen's mealy-mouthed though radio-friendly version of “Louie Louie”, and say, Black Flag's grinding, raucous reinterpretation.

At the Chicago Alternative Comics Expo (CAKE) back in June, and over e-mail this summer, Josh and I discussed his round-about approach to autobiographical comix, contributing art to David Bowie and Marilyn Manson music videos, discovering punk rock, and the latest issues of Raw Power and Rom. Issue two of Rom makes its debut at the Small Press Expo (SPX) this weekend.

BRANDON SODERBERG: What made you begin this “cover comics” project?

JOSH BAYER: There was no master plan when I began Rom, though in some ways, I feel like “covering” or feeling free to appropriate is something I’ve been leading up to for years. I’ve always been excited by the idea that originality is a fucking red herring. People talk about being original like it’s so beneficial to everybody, but it isn't. I remember a Kathleen Hanna interview in Maximum Rock & Roll where she was like, “People say that I sound like Poly Styrene [vocalist of the '70s punk group X-Ray Spex, best known for “Oh, Bondage Up Yours!”] but I don’t take that as a negative thing. I’m not into the the novelty of the new.” I really love that phrase, “the novelty of the new.”

SODERBERG: Do you think “cover” is an accurate description of what you're doing?

BAYER: I think “cover” is a good term. My Rom stories are loose adaptations. I change the names of all the characters except Rom, usually. I call the Dire Wraiths [from Rom] Verminous Knids after the villains from Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator because they are really, really similar. I'm willing to get things wrong and I've found out that a fuck-up can be much more interesting. It fits with my aesthetic of scraping together the book with scraps of bubblegum and shoelaces.

SODERBERG: Why Rom specifically?

BAYER: I picked Rom because it was a blank slate to me. The frame part of my Rom #1 where the kid is reading it? That isn’t me. The Rom comics actually left me really cold when I was young, but Rom is still autobiographical. Rom is a stand-in for the comics I cared about at that age. And the elements of the kid Seth’s life are like my life. I tried to represent the shitty little basement room that I had. It didn’t have a fourth wall, it was like three walls and shitty bookcases in front. And I hated my shower, it was like this like raw cement that was all exposed...

SODERBERG: Basically, covering Rom allows you to do autobiographical comics that don't suck? Issue one has a frame of Seth reading Rom, and issue two has a back-up story that focuses on Seth at school.

BAYER: Yeah, doing the Rom cover comics is just some weird device that measures how uncomfortable I am with telling a real autobiographical story. Each time I do a Rom story, I let whatever fragments I remember from around that time enter the story. But not like an episode of Seinfeld where everything ties together. More like an Italian neorealist movie, where it’s just two pieces standing side by side – the comic and life during that time periods – and readers can make the connections. So, if I did an issue from 1985, I'd probably write about something that happened when I was 15 years old. Originally, when I was working on this issue of Rom, I wanted to write about December 1980 when John Lennon was killed, because that was a really weird period of my childhood. But the longer I worked on issues #31 and #32, the more I felt like I needed the whole thing to come together on every level. Even that conceptual level of having the fact and fiction match up chronologically. And the issues I was covering came out in 1983. I couldn't have "Seth" reading that issue in 1980. Even though most people wouldn't know or care, it would bother me.

SODERBERG: You said that Rom wasn't a comic that meant much to you as a kid. So, when did you realize its potential?

BAYER: When I worked at a comic books store later on, I spotted one or two Rom issues. I picked up issue 29 [the basis for Bayer's Rom #1] and I was like, “This is great.” This big fucking metal guy crawling through an underground sewer hunting this monster who’s despised. I mean that’s rich in and of itself. They are all so fucking sad, as well. Rom is an amazingly emotional comic. I'd like people to find out for themselves about the original Rom issues. And I think it's cool that if they seek them out, they would have to go actually find them on eBay. It's not easy to find the books online to download. It's almost a throw back to a pre-internet time when you would hear about stuff by word of mouth.

SODERBERG: For Rom #2, why did you pick issues #31 and #32?

BAYER: Those issues have all the things that made Rom great: Horror, sci-fi, middle American values. It's got all these amazing moments. Like, the convicts getting spun around until their bodies are ripped loose of their skeletons. Or the dialogue when Rogue kisses Rom and how violated and self-righteous Rom gets. The sexual angle they get into with the villain, Hybrid. It all comes from a very authentic place. I always got the sense that [Rom writer] Bill Mantlo dug what he was writing about the same way that Philip Guston dug painting those piles of legs, and Hitchcock loved to do films about murder, fear of imprisonment, and voyeurism. It's like these guys have a fetish for these things, or maybe they found making work about those themes liberating.

SODERBERG: There's also this other layer to your Rom stories: Mantlo's tragic injury which ended his comics career.

BAYER: For people who don’t know, Bill Mantlo, who wrote Rom, has been in a home for cranial trauma for over twenty years because he was hit by a car in 1992 while rollerblading. It was a hit and run and it’s a really awful outcome for somebody who had so much to say – especially for a mainstream Marvel writer. I was actually going to have an ending in Rom #1 where I showed Bill Mantlo getting violently hit by a car and all the details of his accident.

SODERBERG: You ultimately decided not to draw it, though?

BAYER: No, I drew it. But I also made friends with Mantlo's daughter, and it just felt a lot different after that. I don’t think his daughter is going to want to see the worst moment of her family’s life depicted by a fucking stranger like me.

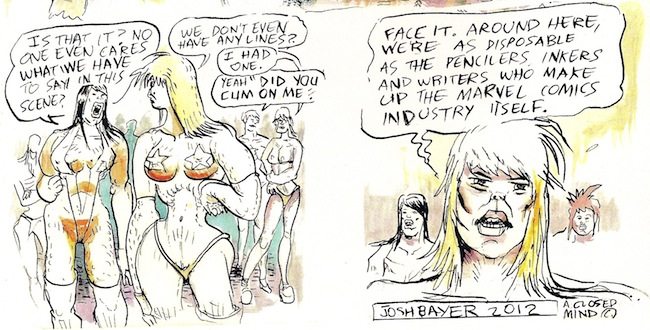

SODERBERG: You've made powerful, emotional comics out of creators' rights issues. It's hidden inside of Rom and then there's “The Future Is Unwritten”, the story you did for Drippy Bone Books' Marvel Comics Presents anthology. In that one, you have all these superheroes at this strip club partying and then they are confronted with the terrible fate of their creators.

BAYER: It’s interesting because at C.A.K.E. somebody came by and bought that comic and said, “I know all the people who are on that cover. I know Rich Buckler, I know Steve Gerber.” It really set my teeth on edge. I was afraid he was going to flip through it and be like, “I know these guys and you’re taking liberties and you’re showing them all falling out of their chairs dying.” It’s kind of insensitive, you know? I try to be decent. I try not to exploit everybody who comes in my path, but writers do that, you know?

SODERBERG: Then, in the final few panels, the strippers from your comic call all comics creators out, including you, for always marginalizing them. You challenge all of us comics dorks blathering about creators' right by flipping the story on the last page and reminding us of comics' long history of terribly representing women, which continues to be overlooked. I love that. Like, even the creators' rights zealots are confronted, here.

BAYER: I do see that piece as a bit of protest art. Feminists might think that is disingenuous. I don’t mean about that strip specifically, but about me right now in this moment, talking about feminist issues. I've been aware of feminist issues since the early '90s and you know, I’m not a fucking huge practicing feminist and it’s hard for any male to call themselves a feminist, and it’s hard for you to call yourself a feminist if you don’t do the homework.

SODERBERG: When that Tumblr controversy about your 'Stop Cartoonists' strips with Pat Aulisio happened (read Tom Hart on it here, and see Josh's amended version of the strip here), I was surprised no one pointed out that you'd recently made a pretty explicitly feminist comic.

BAYER: The Marvel comic, I did instinctively. It’s nice to hear you say that it looked like it was all designed to eventually have this one-two punch at the end where I brought up women’s issues. I just thought it belonged in there. I didn’t plan to do it in the beginning, but I put it in there because I thought that had to be answered for.

SODERBERG: It would be wise to acknowledge that we are two males discussing this topic and so we carry a lot biases whether we intend to or not. But I also want to say that I see “The Future is Unwritten” as a feminist ally comic, even if you don't feel comfortable saying that. That said, the offending strip, which found you and Pat beating up female cartoonists, did upset people. What are you thoughts on that controversy?

BAYER: There was a lot of argument back and forth after I did a series of strips called 'Stop Cartoonists' about Pat Aulisio and I beating up bad cartoonists. And in one strip, all the bad cartoonists were women, and some people got very upset about it. But part of the point of that strip was supposed to be that these versions of Pat and I look like idiots and that the girls who the characters in the comic attack seem genuinely interesting and cool. On a personal level, the fact that people told me that strip triggered them and that I had alienated people, and that I was part of rape culture was horrifying. Even though it was uncomfortable, hearing from a vocal, politicized part of your audience can create a good dialogue, be provocative and create growth. However I think the politicized Internet comics community in general has become combative and toxic. I choose to embrace the "growth" side of the dialogues that I'm involved in and ignore the parts that are destructive.

SODERBERG: Let's discuss Raw Power, which also had its second issue come out this year. It's such a fun book to describe: A Cat Man who saw his parents murdered becomes a punk-fighting vigilante inspired by G. Gordon Liddy's memoir. Then swirling around that is this alternative history conceit wherein punk rock was successfully squashed by the government. How did you develop the ideas in Raw Power?

BAYER:A friend of mine, Joaquin de la Puente, and Erick Lyle, who does Scam, were talking over a weekend and we just started spinning off each other. Joaquin thought up the idea for the Cat Man. Not as a comic, but just like, “What if there was a cat man dude and he becomes Cat Man because a guy kills his parents in a rat mask?” And I added the punk connection. He just hates punks because he sees these rat punks from when his parents get killed and he makes associations, so when he fights crime, he beats the shit out of punks. And somehow, I think the G. Gordon Liddy thing came out through this conspiracy idea that Jimmy Carter was trying to suppress punk.

SODERBERG: How did Box Brown's Retrofit come to put that out?

BAYER: The way Raw Power developed was Box Brown invited me to do a book for his publishing company Retrofit and I was going to do a partially autobiographical story about growing up and my dad not letting me get Mr. T’s autograph. Then, about four months into doing the story, my dad got leukemia and I didn’t want to go back and revisit this kind of frivolous story about my childhood where he comes off like a jerk. So, I thought up Raw Power. I needed a comic idea. My dad eventually died from the leukemia and I definitely did not want to deal with my family shit in a comic.

SODERBERG: Why did you decide to do a second issue of Raw Power? It seems like a stand alone story. Yet, adding a second part makes you sit with this character longer than you maybe you wanted. We get to see him post-“glory.” Out of jail and back on the streets.

BAYER: I can't remember exactly how the sequel evolved. I listen to what my readers want and so, when people asked when the second book was coming out, I started working on it. It gave me a chance to do an homage to Pete the Tramp from Dick Tracy. The third part will restore any sense of balance that's been disrupted.

SODERBERG: Also, the Cat Man is just a really compelling character to return to and explore some more.

BAYER: Cat Man is a character who navigates the world in a really brain-damaged way. Like, someone who's really high, just relating to heat and light and sound and instinct. I'm not trying to be self deprecating and I'm the opposite of stoned, but I relate to that a lot. That's how I am creatively. I grope around a lot in confusion, get an idea, jump on it and then latch onto it with unwavering conviction. I returned to comics in my thirties after a long break. Since then, I've only stopped doing a comic once or twice because doubt crept in. I let doubt creep in when I was in my early twenties. I stopped for no reason and I will never do that again. Every cartoonist I talked to knows this phenomenon of chasing something that sometimes disappears when you try to capture it on the page. Except Johnny Ryan. He called me a nerd when I asked him about this type of stuff once.

SODERBERG: When did comic books first enter your life?

BAYER: I was exposed to comics really early on. My dad worked at a library at Ohio State University, and I’d visit him in the library and they had this one little ghetto where they kept all the big, oversized comics. I’d just, like, pour over those things: Buck Rogers reprints from the ‘70s, Skippy by Percy Crosby, The Great Comic Book Heroes by Jules Feiffer, the Smithsonian reprints. It’s not like now, with all of these huge, huge collections. When I was a kid, you could probably list the oversized reprint books on a couple of hands.

SODERBERG: What about more underground or alternative stuff? When did you discover those kinds of comics?

BAYER: My local library had Harvey Pekar reprints. I saw those when I was about 11? Like, in eighth grade. Reading them so early, the only ones I could understand were the really childish ones. Like the one where Harvey Pekar is talking about how he looked up all the Harvey Pekars in the Cleveland phone book. And how when he was a kid, all the kids would tease him and say “Harvey pees-in-a-car.” It was kind of radical to read those. Like, he’d do a comic where he’s speaking right to you, and there’s a repeated frame for pages and pages. And even though it's easy to repeat the same image, I understood that was still a comic legitimizing the kind of comic that doesn't have a lot of action. That was really radical! Just having a shot of Harvey Pekar looking right at you for twenty pages. Sort of a high art idea compared to what I had been reading.

SODERBERG: When you're a kid used to superhero comics and old strips, alternative comics can seem really strange and subversive. Do you think it helped you to discover that stuff pretty early in life?

BAYER: I think that there are people who never make the leap away from mainstream comics and I think the earlier you get that example set for you, the better. Though I suppose you could put that shit in front of some people and they just wont care, whether they’re age 11 or age 50. But with me, encountering alternative stuff? I was in Columbus, Ohio, you know? It wasn’t a hotbed of high culture. So, finding that stuff was really important. And then when I was 17, I started to see the shit the Raw imprint was printing and that was really really important too.

SODERBERG: Your brother is Samuel Bayer, visionary music video director perhaps best known for Nirvana's “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. He was a big influence on your work and something of a mentor, right?

BAYER: My brother had made it in Los Angeles as a director and he invited me out there when I was 24. He was like, “Don’t worry about rent, don’t worry about anything. I hate it that you don’t have a life. Let’s get something going for you.” So, I came out to L.A. and I stayed out for about eleven years. Then, I moved to New York in my thirties to go to the School of Visual Arts after getting on Wellbutrin to deal with my ADD, which had been preventing me from achieving a lot of goals. I've been in New York since 2005.

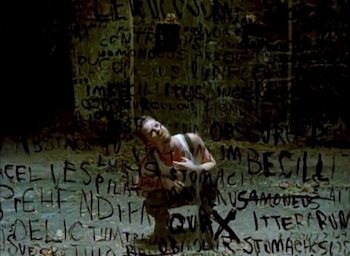

SODERBERG: You contributed art to his videos?

BAYER: I worked on a lot of his commercials and videos. I developed a lot of my work ethic by working with him. Those jobs were really cool. My brother would get an idea in his head and he would let me go crazy with it. He would do a David Bowie video and he would say, “Do a huge word from a song lyric on the wall.” He’d give me a big, fat brush and have me write, like, “the heart’s filthy lesson” on the wall. That was super fucking fun. And I thought what I was doing was easy, but then I’d see other people do it, and they couldn’t fake the crazy line that I had.

SODERBERG: Do any video experiences stand out in particular?

BAYER: He did this Metallica video, “Until It Sleeps”, where I took all these Latin words and I didn’t even know what they meant, and I’d paint them on plexiglass and they did tons of shots with the band performing the song in front of my plexiglass. There was a Marilyn Manson video, “Disposable Teens”, that I was really proud of. They got these paintings of Jesus and I was supposed to defile them and there were all these references to Altamont. You had Marilyn Manson dressed like the Pope in the front and then you have Jesus in the background with the words “Altamont ’69” dribbling out of his mouth. Smearing paint, you know, appealed to the part of me that never got through the anal stage: Smearing huge lines, letting it drip, putting little edges on the letters and stuff. And my brother would be like, “Look how amazing that looks!” Whatever intuitive thing I had that I was bringing to the table, he helped draw out of me. His vision was that I should become a sort of Basquiat-style artist, and continued to do big, smeary, line-driven pieces. Ultimately, that was something that had to get assimilated into the cartoonist that I am now. Luckily, he's supportive of that.

SODERBERG: Your comics maintain that "Basquiat style," though. There's a maintained messiness to your work that's really invigorating.

BAYER: My process continues to be a little messy. Like, I do my shit in sketchbooks. Sketchbooks keep all my pages in essentially the right order without losing them, and I can carry them around and I can carry my ink with me. But the only reason my work's not all over the place is because I went to SVA. SVA showed me a way to organize. Before that, in the nineties, my shit was so messy. Art really took my life right down the toilet because I could live in L.A., but I couldn’t afford my own studio, so I’d just turn my apartment into an art hovel. I just had like buckets of slop water and art materials all over the place. I just had reams and reams of big pieces of artwork. It was impossible to frame them cheaply, it was impossible to sell them unless you were a big name. It was hard for me to live neatly with this work in my life. Comics books are tidy, comparatively. Comic books, I can compartmentalize. Like I can put them in a fucking bag and work in a coffee shop.

SODERBERG: I want to talk about punk which seems like a huge influence on your work. When did punk enter your life?

BAYER: Not until high school. Before that, I remember all the kids had record collections. And I remember not relating to the music. And I remember getting really pissed at myself because I couldn’t remember the difference between Bruce Springsteen and Rick Springfield and I didn’t understand how Def Leppard had like seven fucking albums and what the difference between them and some other band was. I didn’t understand how the guy who wore the sleeveless British flag shirt wasn’t the singer but was somehow the most emblematic member of the band. I remember feeling really inadequate that I didn’t love these bands. And then, in high school, I had a couple cool friends and had a few cassettes come my way and discovered punk.

SODERBERG: What was it like discovering punk?

BAYER: It was a real feeling of vindication. Like, you know, I was correct to not like these bands because when I discovered these great bands, it was like this super heightened sense of being called upon. I remember listening to the Gun Club and just realizing that I’d never been into an album like The Las Vegas Story. And then, I got out of high school and I found a garage sale and I found Agnostic Front and Joy Division and Birthday Party on cassette. I got all of these albums for like nine dollars.

SODERBERG: Punk and comics kind of converges for you with Raymond Pettibon [best known for his Black Flag album art], who you eventually befriended. How did your relationship with Pettibon develop?

BAYER: I was exposed to Pettibon’s work when I was eighteen. Then, ten years later, Pettibon, who was notoriously a super reclusive guy, suddenly was out and about. At that time, he was doing a workshop at Cal Arts. I crashed the workshop and went in while he was teaching and just acted like I was part of the class. I got busted in the middle of the class and he noticed they were trying to throw me out, and he said I was with him. He just recognized I was a big fan. With most people, fandom makes them back off. Pettibon’s really unique because he can encounter somebody who is a really fervent fan, and he takes that as a great compliment and treats them as equals. So, he treated me like an equal. He started giving me a lift to the class and all of a sudden I’m in the guy’s home. He had all this history around him.

SODERBERG: In your interview for Inkstuds, you tell that anecdote about Pettibon working on a show and allowing his pieces to go up in a completely random arrangement. Did Pettibon show you how important chaos is? It often feels like your comics are improvised. What is your process for putting together a comic?

BAYER: Not improvised at all. There’s a point where I get the plot together and I let it marinate and usually ideas come to me. So I write a basic story and then I sit down at one point, and I write the plot and then I carry it with me and sit down another day and storyboard it and the next thing I know, I have a big messy sheaf. It’s usually written on the backs of a bunch of other scrap paper but I’ll have that all stapled together and then I’ll start to map out the comic. In some places there will be a flurry of notes, other places there will be back and forth dialogue, some places will just be some indication I need to draw something here. But I basically have the length at that point. Then I ask myself if it feels like a sincere project and if it feels like an advance over what I've done before.

SODERBERG: So, it's all pretty planned out?

BAYER: It’s definitely planned, but there is an element of me shoving this dirty sheaf of paper, which is all stapled together, into a bag and sometimes I’ll lose pages and then I’ll find them again. So there’s that element of chaos and thank goodness because sometimes you’ll find that you wrote notes initially that are funnier than anything that you can come up with if you tried to do it a second time. And there will be a certain point when I’m writing where everything comes spurting out of me, and that’s really enjoyable.

SODERBERG: That's what stands out about your work, I think. There's all of this energy bursting out of it. Do you get those spurts often?

BAYER: That spurt, where you’re getting everything down quicker than you can think it up, should only happen about once a year or something. I’ve read about that in writing books and it makes me feel like I’m on the right track if I ever have that happen. If I am on the right track is for other people to say, though. I mean, a big goal of doing these comics is giving myself a project that keeps me distracted from the horror of this modern world for seven months. I don’t know. Maybe that’s a horrible example to set for people, but that’s what I am doing.