As if it wasn't enough that comics are the domain of the obsessive control freak, there is a cartooning sect that perfectly defines the creative mania responsible for some of our greatest works: the one-artist anthology. It's a publishing sensibility that may have had its moment in the sun decades ago, but it's never really been a dominant point of interest for cartoonists. That's not surprising; carrying the weight of multiple narratives issue after issue is not particularly alluring to those who just want to draw cool stuff for a page rate, or for those who just want to tell their stories one book at a time. What may seem like a dated platform to some may still be a viable option for those who would rather pace themselves as such, and for readers who appreciate the richer values that only this format can provide. I traced the lineage of the one-artist anthology to the underground comix movement, I waded through the black & white boom as well as the '90s glut, and I examined the slim offerings that our current dry spell is responsible for. Looking back has reaffirmed my belief that some of the highest achievements in comics are results of the finely tuned succession which only the one-artist anthology format can lay claim to.

Starting Point

Robert Crumb is responsible for every single line in all twenty-eight pages of Zap #1. It was 1968, and Apex Novelties published the collection of different comic stories during the emerging counterculture. This first Zap issue wasn’t technically the first full comic book that Crumb had drawn, though. Brian Zahn intended to publish the contents of what would later be Zap #0 as early as 1967, but that plan fell through when Zahn left the country with the original art. Crumb found photocopies of the pages and had them published as Zap #0, which was released after #2 came out in ‘68. What we’re left with is two solid issues of pure Crumb unencumbered by any type of demands outside his own acid drenched discernment. Crumb wasn’t interested in branding himself through a comic-book title, either, much to the chagrin of mentor/friend Harvey Kurtzman. Crumb kept changing the identity of the comics he was doing every issue. In just two years, he independently created entire stand-alone titles such as Despair, Uneeda Comix, Homegrown Funnies, Your Hytone Comics, XYZ Comics, The People’s Comics, and Snatch Comics (with six pages by S. Clay Wilson). Kurtzman wondered why Crumb hadn’t built a solid home front for his work, the way Kurtzman had done with MAD and Help (not so much with the short-lived Trump and Humbug). Regardless, Robert Crumb had virtually created the one-artist anthology from scratch, producing page after page of everything that came to him. It’s a method that has worked for him throughout his career.

Robert Crumb is responsible for every single line in all twenty-eight pages of Zap #1. It was 1968, and Apex Novelties published the collection of different comic stories during the emerging counterculture. This first Zap issue wasn’t technically the first full comic book that Crumb had drawn, though. Brian Zahn intended to publish the contents of what would later be Zap #0 as early as 1967, but that plan fell through when Zahn left the country with the original art. Crumb found photocopies of the pages and had them published as Zap #0, which was released after #2 came out in ‘68. What we’re left with is two solid issues of pure Crumb unencumbered by any type of demands outside his own acid drenched discernment. Crumb wasn’t interested in branding himself through a comic-book title, either, much to the chagrin of mentor/friend Harvey Kurtzman. Crumb kept changing the identity of the comics he was doing every issue. In just two years, he independently created entire stand-alone titles such as Despair, Uneeda Comix, Homegrown Funnies, Your Hytone Comics, XYZ Comics, The People’s Comics, and Snatch Comics (with six pages by S. Clay Wilson). Kurtzman wondered why Crumb hadn’t built a solid home front for his work, the way Kurtzman had done with MAD and Help (not so much with the short-lived Trump and Humbug). Regardless, Robert Crumb had virtually created the one-artist anthology from scratch, producing page after page of everything that came to him. It’s a method that has worked for him throughout his career.

Only Journeymen

An unlikely candidate for a one-artist anthology is a Mike Sekowsky issue of Showcase. This was the tryout title for DC Comics and each month featured a different lead character. Sekowsky was left to edit, create, write, pencil, and most likely color the last six issues before its projected cancellation. He devoted entire issues to stories such as Jason’s Quest and Manhunter 2070, but it was specifically in issue #90 where he placed a teen romance adventure up against a couple of his space thriller pages and threw in a faux-house ad for upcoming stories, to boot. Such complete control in a mainstream comic was unprecedented (the next notable example would be Jack Kirby’s return to DC five months later), yet there’s no coincidence that such freedom was available in a title with little hope for success.

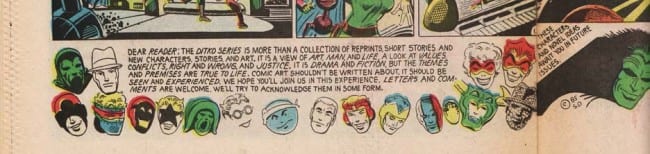

Inspired by his contribution to Wally Wood’s self-published anthology Witzend, Steve Ditko took the black & white small press plunge with his sociopolitical Avenging World (’73) and two issues of his Objectivist vigilante Mr. A (’73 & ’75). It wasn’t until his next comic, Wha--!?!, published by Bruce Henderson, that Ditko decided to introduce several thematically different characters in their own tales. That single issue allowed Ditko the room to meld his philosophy with the physical heroism he perfected at Marvel and DC, along with a couple of random morality plays. It was the first superhero one-artist anthology. Ditko wouldn’t return to the format for another decade with two full color issues of Charlton Action, edited by Robin Snyder. There, Ditko presented his Static character as the main draw, but the back-ups varied in focus, mood, and even page layout. This led to three dense issues of Ditko’s World, published by Renegade Press. It was as if Ditko could hardly contain his swelling of ideas and imagery, with most every corner of these comics furnishing his stamp. Of his generation, Ditko was the only one who continually expressed his beliefs through this setup, and he certainly had a strong enough voice to carry it through several decades.

Somewhere In California

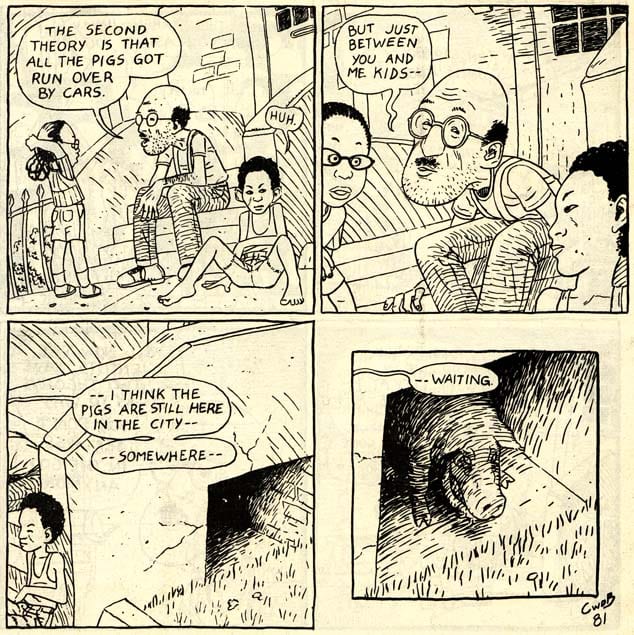

Love and Rockets is more of a two-artist anthology (three-artist for the first few issues), self-published by the Gilbert, Jaime, and Mario Hernandez back in ’81, and picked up a year later by Fantagraphics. The title was a healthy mix of individual stand-alone tales, recurring characters, and all types of genres. From quasi-autobio, romance, and adventure to urban culture, art history, and exercises in made up languages. Concentrating on his sprawling Palomar stories didn’t stop Gilbert from throwing in stories about old punk 45s, Adrian Adonis, or locker rooms. Even the back covers were more excuses to just… try shit. They were inspired and unafraid of the trends of the time and the editorial forces that wouldn’t even know what to do with such work. This was before there was any “alternative” scene or built in audience for this stuff. Love and Rockets was their world and these were the conditions the Hernandez brothers were setting.

That type of authoritative abandon is the essence of the one-artist anthology. Love and Rockets remains a complementary two-artist institution to this day, but make no mistake, the Bros. got to that level on their respective terms.

That type of authoritative abandon is the essence of the one-artist anthology. Love and Rockets remains a complementary two-artist institution to this day, but make no mistake, the Bros. got to that level on their respective terms.

Insane Masochists/Creative People Make These

So far we have Crumb, Sekowsky, Ditko, and the Hernandez Bros. as a sort of template to go forward from. Allow me to dote on a few follow-up notables.

Chester Brown’s mini-comic, Yummy Fur, was made from ’83 to ’85, when Brown individually distributed it to book and zine shops in Toronto, lasting seven issues. Vortex Comics reprinted the material in ’86 starting with a brand new first issue. Brown went on to produce new and original content after the reprints ran out, causing Yummy Fur to reach seminal heights within the burgeoning independent comics community. The most prominent stories to emerge from Yummy Fur were “Ed, The Happy Clown”, an adaptation of the Gospel of Matthew, and Brown’s own autobiographical material. Yummy Fur switched to publishers Drawn & Quaterly for the final eight issues before concentrating on a different story altogether in '94’s Underwater.

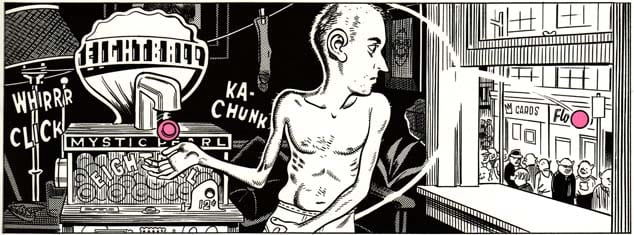

Throwing a monkey wrench into the chronology I’ve set up, but worth isolating due to its impact, Dan Clowes hit one of the highest notes in comics with his very own version of MAD Magazine in ’89: Eightball. Published by Fantagraphics fresh off his run on Lloyd Llewellyn, Clowes used this last-ditch effort to create one of the best comics of the 20th century. To elaborate, "last ditch" in this case meant a final attempt for Clowes to do exactly what he wanted to do through comic books. Dissatisfied with his previous work and the industry he operated within, Clowes told his demented and hilarious stories without fear of being denied, disliked, or ignored. Like the Hernandez Bros., Clowes was pushed to greatness when backed against the wall. Eightball hit its stride quickly, but Clowes was on fire when he lined his razor sharp hilarity with stories such as the poignant “Caricature”, the nostalgic “Like A Weed, Joe”, and the eerie “Glue Destiny”. Eightball is a masterpiece, a standard every cartoonist should take a cue from.

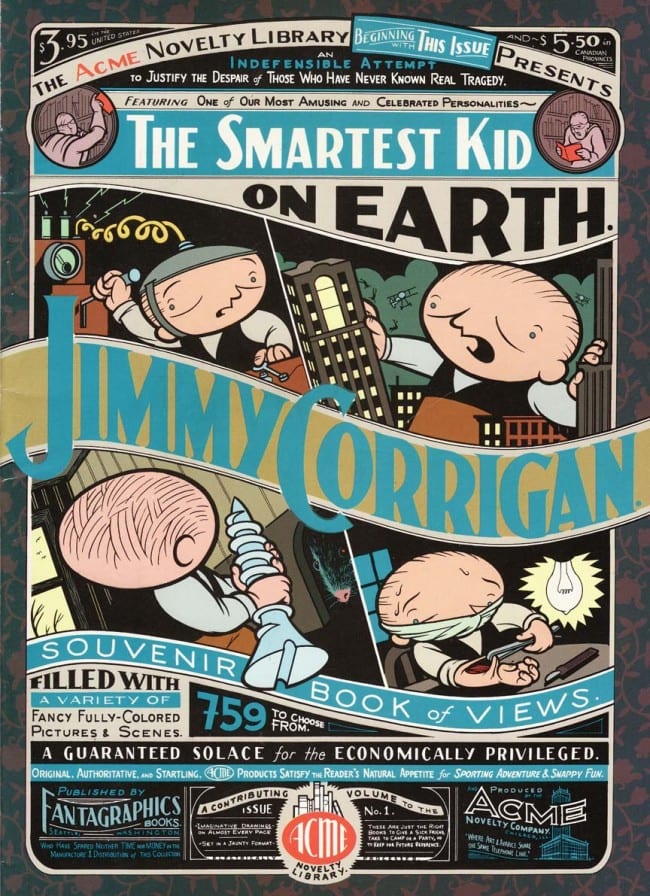

With one more detour from the timeline, Chris Ware rounds off this portion of exemplars by virtue of his Acme Novelty Library, first published by Fantagraphics in '93 (well after the one-artist trend had formed). Taking control of the form with unparalleled precision, Ware made every issue of Acme into a work of staggering caliber. This periodical-as-art was always changing in size, length, theme, and with a masterful attention to detail. Ware treated the medium with respect (a respect it perhaps didn’t deserve) and created a layered, personal opus on mere sheets of paper. Acme is a true testament to the value of the single issue, the very value of comics, and although Ware mainly serialized his Jimmy Corrigan story, he never let a chance to put together a one-artist show go to waste, #15 being the last and most diverse one.

The Deluge

After their initial step with Love and Rockets, Fantagraphics published most of the solo comics in the mid- to late- '80s and beyond: Peter Bagge created a slew of characters under Neat Stuff (’85), Jim Woodring had a dream comic called Jim (’87), Joe Sacco’s miscellany was found in Yahoo (’88), Scott Russo’s Jizz (’91) managed to last ten issues, while Al Columbia pumped out a couple of beautifully drawn The Biologic Show comics (’94) before realizing that plots and schedules were for suckers. Julie Doucet documented her growth as a cartoonist by self-publishing Dirty Plotte (until D&Q began publishing it, same thing happened to Adrian Tomine’s Optic Nerve). David Mazzucchelli switched gears from being a highly acclaimed mainstream artist to self-publishing his RAW-inspired anthology, Rubber Blanket, in ‘91. In just three (now out-of-print) issues, Mazzucchelli showed off extensive growth as an artist, a writer, and a publisher, creating some of the most memorable comic book short stories in the process. Johnny Ryan self-published his Angry Youth Comix, Mary Fleener released three issues of Fleener by way of Zongo Comics, and Evan Dorkin was consistently funny in his jam-packed Dork comic from Slave Labor Graphics. Let us not forget Dame Darcy’s Meat Cake, John Porcellino's King-Cat Comics, Ivan Brunetti's Schizo, Dylan Horrocks' Pickle, Sam Henderson's Magic Whistle, Jessica Abel's Artbabe, Jay Stephens' Sin, John Kerschbaum's The Wiggly Reader, Carol Lay's Good Girls or the Hernandez Bros. striking out on their own with Gilbert’s New Love and Jaime’s Penny Century. Finally, as someone who was always at odds with the mainstream, yet such a fixture within it, Barry Windsor-Smith crafted nine (out of a projected twelve) issues of his Storyteller series through Dark Horse Comics in ‘96. A couple of the serializations within that title were later individually collected and published by - you guessed it - the "home of the world's greatest cartoonists." That's no joke; you can see that they published most of the titles I've listed. Wouldn't you brag?

Curiously, with Fantagraphics being the primary publisher of most of these one-person showcases, we’re left to wonder whether it was due to their fierce encouragement of an artist’s vision (and the singular anthology was what those respective artists wanted to make in the first place), or if those respective artists saw that Fantagraphics was publishing this sort of format, thus nudging themselves in that direction for an easier shot at being published alongside the top of the line in alternative comics. Not to suggest that the post-Clowes wave of creators had mercenary intentions (especially since the format was never a cash cow) but there was definitely a new guard forming at the time. Although that new generation was still in its infancy, it was very much being cultivated by a single publisher. One can’t blame a creator for trying to adapt, including Ware, and it doesn’t make them any less noble for trying to find their way. As evidenced by the list above, a lot of those titles barely made it past a third issue. Whether or not it was part of the indie zeitgeist at the time, the one-artist anthology wasn’t an approach that agreed with everybody.

The Drought

The mid- to late-'90s were tough all around for comics. As the decline in sales can attest to, the collective disinterest in the medium leveled the industry's morale as well as its bank accounts. The audience who once humored it dwindled all across the board. Time passed but comics never went anywhere; they didn't die the way it's always predicted every few years. This time, though, graphic novels proved to be the thing that people wanted, as did the bookstores, as did the creators. Who in their right and respectable mind would play with a disposable item such as a comic book? Serious stories needed spines, better paper, and more importantly they needed larger page counts. What they didn't need was to mess around with limited distribution, serialization, or handwriting indicia every single issue. Not many comic book creators have the resolution or the patience to juggle every chore it takes to make a complete comic, but most that do would rather spend their time crafting their very own graphic novel.

The downside of the preoccupation with making larger works is that it has yielded some pretty bloated and unreadable attempts at making both serious art and garbage culture. There's something to be said for honing skills over the years to the level where one can fill up those hundreds and thousands of pages of something worthwhile, but it's no longer a question of doing something well, it’s about simply doing. It’s no fault of the graphic novel, though; even on the level of a single issue, excellence isn't on the menu because going beyond the basic level of aptitude is hardly ever rewarded in comics. The current, prevalent agenda seems to be cranking out page after page no matter what, as creators pray that the law of averages will favor them. There may be hope yet, though, because if there’s anything to be learned from following these one-artist anthologies, it’s that beauty can indeed take root in low rent conditions.

Only Way

Thankfully there have been a few blips on the radar. Ryan’s Angry Youth Comix went official in ’01 via Fantagraphics, who also released Jordan Crane’s Uptight and Sophie Crumb’s Belly Button Comix. Sammy Harkham had Crickets published by D&Q but it was cancelled after two issues; he now self-publishes the title. AdHouse Books put out an issue of Zack Soto’s Secret Voice, which promised subsequent issues. Nick Bertozzi created four issues of his Rubber Necker series from Alternative Comics before concentrating on graphic novel work, but he recently returned to the fold by making the fifth issue as a mini comic. DC’s Solo series, edited by Mark Chiarello, was more of an artist’s showcase than a real deal one-artist anthology, but the strongest issue of the bunch was Brendan McCarthy, who best took advantage of the single issue concept. His was the last of the series before cancellation.

Kevin Huizenga came through with Supermonster, and has since also created a system in which to catalog his work project by project. Instead of springing back to one umbrella title, Huizenga appoints every comic he makes with a KH number, making that designation somewhat of one-artist anthology (not unlike Ditko’s “D” numbers for his aforementioned small press material). Obviously, I’m applying these ethics to Huizenga’s work while projecting my own fascination with the compilation, but I think something as simple as KH numbers can tie it all together in a way that matches my theory.

While there’s no boom for this format on the horizon, we have been witnessing a mild upswing (meaning there’s a faint pulse) with comics such as Ted May's Injury, Lisa Hanawalt's I Want You, Michael Kupperman's Tales Designed To Thrizzle, and Noah Van Sciver's Blammo. Prominent amongst these is Michael DeForge’s Lose. If you zoom out and take a look at the scope of DeForge’s regular output, you’ll see that he has enough short stories, one-pagers, and mini comics to fill in a monthly Lose title. But why limit it to one’s own solitary comic? The key is expansion, no? Notice how this follows Crumb’s publishing trajectory, even Huizenga’s, in that you get your comic out when you can, but you also spread out to as many outlets as you want.

The most unlikely substantial example that comes to mind is the remarkably determined work of Steve Ditko. His all-over-the-map comics didn’t stop in the mid-'80s. Fantagraphics published an issue of his Strange Avenging Tales in ’97, and Robin Snyder published his Steve Ditko Packages, two of them (#1 in ’99 & #4 in ‘00) especially packed to the gills with random material. These days, Ditko continues to carry the torch by putting out individual issues, up to 16 and counting, with nary a connection between the stories. The man is 82 years of age and is still producing black and white comics on newsprint. He was one of the first, and with our waning desire to see such tailor-made work, he may very well be one of the last.

Too Fucking Bad

That’s the business we deal with. It’s not an easy thing to market, being that the mere mention of “one-artist anthology” explains very little. All you know you’re getting is one person’s particular offerings, and who’s to say that such a vague concept is worth people’s time from a salable standpoint anymore? Let’s get past the bottom line pitch for a second… there are also our interest levels as readers to contend with. Have they moved beyond this point, or are we ready to embrace the totalitarian nature of the one-artist anthology? Are there creators still interested in or even capable of perpetuating this branch of comic books? Realistically, is there even an audience for this kind of thing? Artists can try to create their own audience by simply doing what they do and hoping something sticks, but that’s not a business plan, it’s a gamble, it’s a fantasy, and even though comics are built on the hopes and dreams of the stubborn and/or the delusional, performing to an empty room is never fun.

From a different marketing standpoint, the creator would frequently be on the stands with single issues, as sometimes presence is enough to keep readers captivated. On a deeper level, single issues over complete works give the artist the space to develop a relationship with the audience. Overall, it’s a lot of work for a payoff that only a person with a God complex can appreciate. For all of these limits, there is still a powerful charm in having a good, strong variety of ideas forced within a specific pulpy parameter.

It’s a beautiful thing, the modest booklet quietly containing a master’s vision or a genius’ greatest serialized work. Many of our finest were at the top of their game when they crafted entire publications from scratch, works that left defining marks on the world of comics, one issue at a time. One-artist anthologies are love letters that can make you feel like you’re a part of a very specific world, that you’re in on a joke. It’s the ultimate form of expression in modern comics, and we shouldn't be found short of assigning heavy emphasis on its importance. The most perfect of comics have lived and thrived within this cheap method of presentation, and for an art form that can be revisited and re-examined directly from the hand of the creator, it doesn’t get any better than that.

*Front piece image by Gilbert Hernandez, Love and Rockets #49, November 1995