Recently, namely in the tasteful German comics anthology WHOA! #18 I might have claimed otherwise, but actually I'm NOT forgotten by the world – at least not like that guy in the song about Room 506.

Now, you won't earn any recognition for shouting out Dave Sheridan just because of the band name Leather Nun, or, for the sake of being an avid reader of my embedded journalism in the hanseatic cities of Hamburg or Bremen, for precociously mentioning that this text here is actually about Room 404, not 506.

However, Bremen's small gallery Room 404 is back after being exposed, like lots of other cultural institutions, to the straining pandemic that is Covid-19 – though for now it's only available to the limited number of ten people at once.

It seemed for a while that Germany was not faring as badly as a lot of other countries, though its subculture, suddenly working alone in front of empty ranks, had its own food for thought. Now, more than a year since Israeli cartoonists Keren Katz and Rotem of Qiryat Gat hit the floor of the former plumbery, art life has slowly reclaimed its natural habitat.

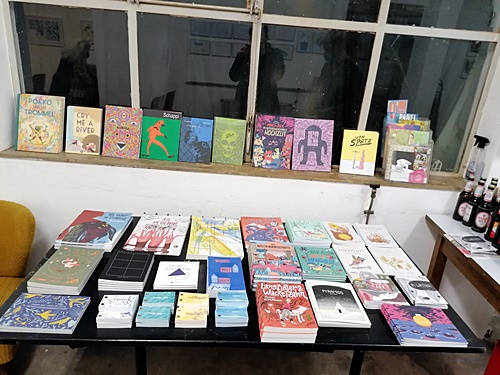

This time around Rotopol Press, the birthplace of the fatherland's indie comics household names like Anna Haifisch or Max Baitinger, as well as assuming responsibility for the German translations of Jesse Jacobs and Anne Simon (while furthermore an institution close-knitted to Kassel's art academy and its Professor Hendrik Dorgathen, who is not only the creator of Space Dog, but also did the beautiful cover for the German edition of Paul Auster's In the Country of the Last Things), sent seven dessinatrices who occupied the entire property the deceased plumber had bequeathed his sisters in mind, here Nina Kaun and Carmen José.

Because, you know: construction and things.

That would be a nice slogan fitting Nadine Redlich's collection of strips called Paniktotem (which translates loosely as "panic totem", you get the idea). She self-defines that work as ambient comics, and if you love to sit through an album like Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks by Brian and Roger Eno plus Daniel Lanois, you'll be in for the ride of your life. Sequences, drastically reduced in their time flow, point out the impossibility of actual movement within a medium being hopelessly rooted in static. The way of hanging was more adequately to her art than Redlich might've imagined: suggested was an endless and repetitive tube of sequential non-movement, thus a cartoonist's meditation. So this will also be the answer you're about to get when checking the FAQ for what nonline aspects could add to art, when they are exhibited in real life.

A completely different wave gets ridden by KIIN., the nom de guerre of sisters Kirsten Carina and Ines Christine Geißler. They successfully manage to capture the synesthesia born out of a sunny day at the sea, the distorted perceptions that come as a result of searing sunlight entering through narrowed eyes. These impressions get translated via bodies frolicking at a sandy beach, whereas swimsuits and the sand merge in yellow gradings with surroundings changing between brown and orange and finally leading to shapes getting blurred. Becoming witness to the whole scenery, you just can't help humming the tune of Surf's Up (And So Am I) while the salt of your running tears as a result of the Wagnerian rock combined with your palpebrals squinted reminds you of the taste of the sea – and if that's not synesthesia in full effect I don't know what is.

Julia Kluge is also heavy into shapes and gestalt effects, though not indistinct but precisely cut ones in a way French Leipziger-of-choice Blexbolex would make use of. Decorated with lines lifted from the likes of Germany's romanticism poet Joseph von Eichendorff et al and thrown in seemingly arbitrarily, a modus operandi leading to some nice-to-look-at color shiftings, but not contributing that much to an inductive effect as it is mostly intended by comics. So this works nice within an exhibition, as long as the hanging provides the conceptual elaboration to underline the solitary character of the artwork, but collected you'll end up with some kind of picture book that wouldn't even pass as a graphic novel. But besides my eternally pulsating Poison Heart, the definition of what a comic eventually is, appears like a mighty ever-morphin Power Ranger or, as Love once put it, Forever Changes, and this is the reason for Ley Lines and why I miss Thought Bubbles in more than one way.

Former Paula Bulling, now Nino Bulling, is firmly expert when it's coming to almost ghostly shapes – as previously shown in Im Land der Frühaufsteher (In The Land of The Early Risers) in which the way of refugees in Germany on their way through the institutions gets picked up as a metaphor for disappearing in your physical form, being exposed to assigned rooms and places beyond your control so you have to haunt these places like maybe in forever. The exhibited works here though were from Lichtpause (which means copying transparent drawings or letters to paper but can also be read as light taking a time out), a lecture in incidence of luminosity and color. It easily shows that those components, usually conceived as not important to narrative in graphic storytelling by a majority of lazy reviewers, are essential to tell a tale – even within an exhibition, by just getting accentuated via a specific hanging scheme, and also, you guess it, a strategic direction of the light. Which had been done, by the way, in perfection in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, when literally staging Marcel Van Eeden's comics hybrid Witness of the Prosecution in 2009.

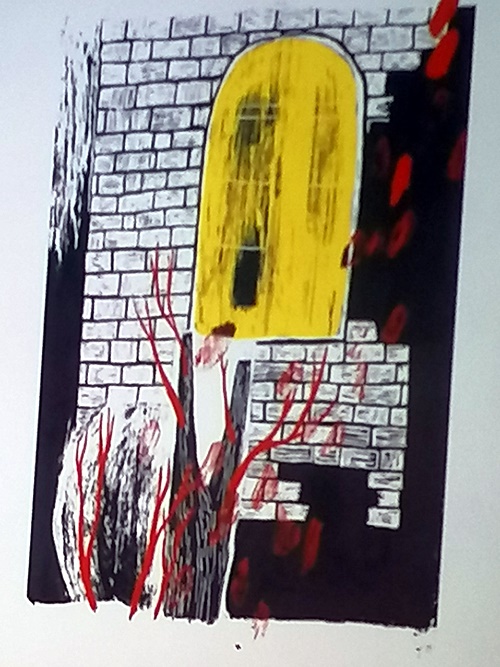

But where spotlighting just isn't enough, you may have to fall back on aural support. Lucky if your husband is a talented composer who manages to provide your dramatic reading with a score inspired by trip hop as well as relying on the neo-classical, apocalyptic folk and yet-to-be-defined sub-genres of industrial music. Not that Nina Kaun's Wie immer im Frühling (Like Always in Spring) sorely needed it, but it enhanced her performance presenting drawings of torn-out shapes crashing into spaces that appeared to be familiar somehow when given a second look. Ideally matched by a text that resembled of Fadensonnen by Paul Celan now and then through a seemingly out-of-place and simultaneously without-rhyme-but-reason variety of words while an outstanding coloring from shrill yellow to dried-out blood red did the rest to lure the audience into a violence-soaked fog made of components only to be described as *thick* while dragging one further in jettisoning melancholy.

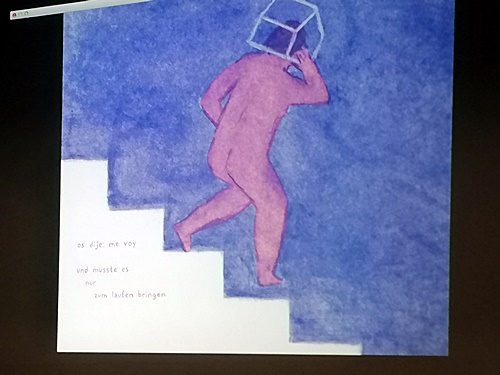

Carmen José concluded in tranquility, reading from the bilingual Allí'/Hier (There (Spanish)/Here (German)). The parts spoken in Spanish gave me spine tingles whilst watching strange fluorescent colors looking like a result from working with crayons. By utilizing connecting/dividing elements and color separations an atmosphere of feeling lost and comfort was ensured in equal parts. The two languages weren't translated, not to the listening audience nor to the readers of the book – there's just a small glossary on the final page of the printed version with some basic vocabulary in Spain/German. Guess what that procedure caused, a feeling of being alienated in your own home. In the end we all left in silence, heading home or wherever to – as long as it wasn't for the dreaded Room 506.

The exhibition, supposed to be open until November 7th, is now closed to a partially lockdown in Germany due to Covid-19.