Nursery Rhyme Comics hasn’t Sendak’s sharp teeth. Indeed at times it shrinks from controversy. Though some pieces mock authority with a nearly Caldecott-like spirit—say, Eleanor Davis’s “The Queen of Hearts,” or Aaron Renier’s “The Lion and the Unicorn”—and others attain a very Caldecott-like verbal/visual irony—Sakai’s “Hector Protector,” or Drew Weing’s “Baa-Baa, Black Sheep”—in most cases the rhymes’ possible implications, or even outright assaults, are soft-pedaled. Lucy Knisley’s “There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe,” for instance, reinterprets the severity of the rhyme—

She gave them some broth without any bread

Then whipped them all soundly

And put them to bed

—in an innocuous fashion, turning the old woman into a benevolent aging rock ’n’ roller and the “whipping” into a musical frolic:

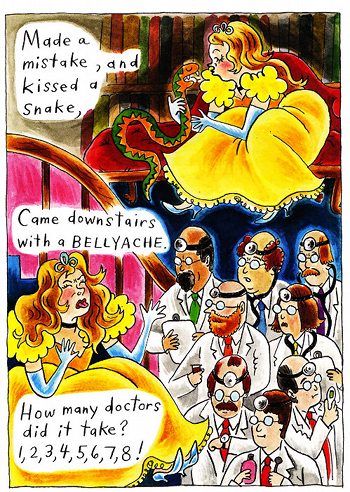

This is clever, as a way of solving a difficult editorial problem, but robs the rhyme of its provoking bluntness. Similarly, Raina Telgemeier’s “Georgie Porgie”—you know, the one about the boy who “kissed the girls and made them cry”—locates the story in an adult-supervised (well, almost supervised) birthday party, where young Georgie’s indiscretion is only a minor outbreak of the carnivalesque within an eminently safe context. Georgie’s face, you see, is smeared with pie, and so he gets a girl messy, hence the upset. Telgemeier stays away from other kinds of inferences that might have been drawn from the poem’s gendered antics. Ditto Vanessa Davis’s “Cindereller,” with its lines about the title girl “kiss[ing] a snake,” getting a “bellyache,” and requiring the help of “doctors,” all of which Davis literalizes, without plumbing the level of insinuation that seems so invitingly there in the rhyme:

(See by contrast Thomas’s reading of “Miss Lucy had a steamboat” in Poetry’s Playground, a veritable minefield of Freudian suggestions!)

There are a number of pieces in NRC that interpret the rhymes with this kind of blank-faced literalism. In other words, some of the comics in NRC are less inventive, or less engaged, than I would like.

Yet NRC does belong to the same tradition as Caldecott, and at its best plays the same game. Some of its contributors play it quite well, that is, creatively, dreaming up unexpected and witty elaborations. If the book doesn’t burn consistently bright, its highlights are high enough, offering startling back-stories and, comparable to Caldecott, finding ways to use the rhythmic resources of the medium—in this case comics—to reinforce the rhythms of the verse. Whereas Caldecott capitalized on the rhythms of quickly-turned picture book pages, the best pieces in NRC capitalize on the potential of the comics page (or in some cases the two-page spread) as structure. The effect is a beguiling kind of visual translation: one rhythm to another.

Davis’s “Queen of Hearts,” for instance, uses elaborate split panels, continuous action, and diagrammatic captions to develop a full story in two pages, one in which characters, plot, and even moral point of view are well realized. Elaborating with aplomb, Davis makes the thieving Knave of Hearts a sympathetic, Robin Hood-like figure out to rebalance an oppressive social hierarchy (in this she is very Caldecott-like):

Davis manages, in a tight space, to build a dense yet highly readable comic. She exploits a particular color scheme and multiple layers of text, most prominently the original rhyme, to guide the eye, also to win our sympathies and set up a delicious implied resolution (you’ll have to see the second page for yourself). This is a smart comic—as good as I’d expect from the author of the super-ingenious Secret Science Alliance and the Copycat Crook.

A similar formalism, with regular panel grids and regular rhythms, marks several other pieces in the book. For example, Marc Rosenthal’s take on “My Name is Yon Yonson” (an infinite looping rhyme rather like the infamous “Song That Never Ends”) uses uniform horizontal strips across the two-page spread, along with bleeds at the top left and bottom right, to imply that the rhyme will go on forever, endlessly cycling through the spread. In a very different vein, Craig Thompson’s sexy (!) adaptation of Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussycat” mixes his usual voluptuous brushwork with a consistent yet fluidly organic design in which ocean waves and other horizontals divide the metapanel that is the page, and bullseye panels visually rhyme with one another as well as with the round shapes evoked in the poem (the wedding ring, the moon):

Likewise ingenious is Jordan Crane’s crazed vaudevillean take on “Old Mother Hubbard,” which builds on a classical six-panel grid and repeating color scheme to emphasize the rhyme’s deadpan absurdism. Naturally, the dog steals the show:

Most delicious in this regard is Cyril Pedrosa’s “This Little Piggy,” in which his lively, hilarious cartooning is laid out as a series of discrete one- and two-tier strips with uniformly sized panels, each devoted to a single line from the poem:

The total effect is one of patterning and repetition but also comic surprise (again, you’ll have to read the whole thing for yourself).

Besides clever formalism, NRC brims with delightful cartooning, from Stephanie Yue’s quick, agile mouse in “Hickory, Dickory, Dock,” through Mignola’s eerie “Solomon Grundy,” very much in recognizable Hellboy territory yet absolutely right for the poem, to Laura Park’s “‘Croak,’ Said the Toad,” with its gluttonous, self-indulgent toad and frog. I laughed at many of the entries, and gazed wonderingly at some too. One of my favorites, Mo Oh’s “Hush, Little Baby,” unites formalism and peppy cartooning, translating the back-and-forth, question-and-answer form of the poem into a cascading series of small panels that tumble down the page, giving voice to the child’s challenges and the papa’s reassuring replies:

That Nursery Rhyme Comics welcomes among its contributors such relative newcomers as Oh, and that these artists contribute some of the best comics in it, makes the book doubly impressive. Diversity in style, outlook, and genre of origin distinguishes NRC’s artistic roster, and enlivens the book, overcoming the occasional timidity of its editorial choices. However, I do wish there were more diversity in the cultural origins of the rhymes themselves. One thing I try to get my students to do when discussing nursery rhymes is identifying ones in languages and traditions other than the Anglo-American, for example in Spanish, Armenian, Thai, or French, because of course there are many such rhymes around the world, and I do have students who know some of them. It’s just that they tend not to think of these rhymes as “nursery rhymes,” because their understanding of the genre has been boxed in by the Mother Goose tradition. While NRC gestures toward greater inclusiveness in its images, most of its chosen rhymes are decidedly English. The inclusion of verse from other languages, with or without complete translation, would only have enhanced the diversity of the project.

Apart from that, Nursery Rhyme Comics is terrific. It doesn’t traffic in playground poetry—it’s not as scrappy and aggressive as that—but does impressively extend the rhyming book tradition that reaches back, through Caldecott, to the very roots of the picture book. Most importantly, there are comics in NRC that I will be reading and gazing at again and again, for their verve, ingenuity, and high spirits.