The other day, for the first time in my life, I was personally offended by kawaii. I have found it silly, gross, frivolous, and stupid on many occasions, but never offensive.

“Wouldn’t you like to have this cute little puppy dog hanging in your house? It’s an image of the artist’s own puppy dog. Wouldn’t you love to share it with your family?” said the beseeching salesman to the old lady in the third floor gallery at Maruzen Bookstore in Nihonbashi.

I was heading back to the subway station after a coffee with a Los Angeles director about a documentary he is making about ninja and pop culture, when I chanced upon a sign outside Maruzen advertising Nakashima Kiyoshi’s print show. This is an artist that recently crossed my radar for reasons explained below, but in whose work I would otherwise not be interested in the least. I popped into the show hoping I might learn something about him, not expecting that that something would be that he’s a weasel.

Nakashima Kiyoshi. Born in colonial Manchuria in 1943. Grows up in a coalmining town in Saga, Kyushu. His grandfather was also an artist, a painter of ceilings and lanterns for temples and shrine. As a child, loves manga. Sends his work to Tezuka Osamu multiple times, but receives no reply. His mother dies when he was seventeen. He moves to Izu and works digging hot springs. After hours, spends time alone teaching himself how to draw. In 1964, he joins an ad agency in Tokyo named Asahi Kōsha, mainly doing storyboards for animated TV commercials. Once his daytime duties are complete, serves as an assistant to Morita Kenji, author of the popular slapstick children’s manga Marudedameo, about a boy and his robot companion.

In 1968, joins Sima Creative House as an art director, where he achieves fame for storyboards, character designs, and illustrated calendars for clients such as Ito En (green tea), Sunstar (toothbrushes), Kikkoman (soy sauce), and Toa Corporation (construction). In 1971, spends six months in Paris visiting museums and sitting in on art classes. In 1976, goes freelance. Works with ex-Tōei animator Nagasawa Makoto as an art director on Kirin’s The House of Know-it-All (Monoshiri yakata), a popular daily (3 minutes per) animated television series. Amongst his fans are manga artist Mizushima Shinji, who said about Nakashima's work, “When you first see his children’s pictures [dōga], they look like manga. But when you look at his draftsmanship, you know this is the real thing. Cartoonists are simply no match.”

In 1976, through a coffee house in the Ginza, Nakashima sells his first framed artwork, fatefully to folksinger Sada Masashi. It shows a little girl in kimono standing under the eaves, a refugee from the rain. Sada wrote a chart-topping song inspired by it, titled Taking Shelter from the Rain (Amayadori, March 1977). He later anoints Nakashima “painter of the wind” (kaze no gaka), a handle that has stuck. In 1982, Nakashima’s imagery becomes nationally known through NHK’s Songs for Everyone (Minna no uta), a music program for children by Japan’s national public broadcasting organization. Soon after, he begins exhibiting watercolors of children in rural settings and neo-classical bijinga (beautiful women) paintings in department store galleries across Japan. In the mid-late 80s, begins receiving a large number of commissions from NHK, solidifying his links with government cultural programming.

In 1987, awarded a prize at the Bologna International Children’s Book Fair for his illustrations for Yoshimoto Naoshirō’s Kodama myōto. Thereafter, continues exhibiting widely and internationally, including shows in Beijing (Agency for Cultural Affairs, 1990) and Paris (Mitsukoshi-Etoile Art Gallery, 2001). In 1988, a cancer-emaciated Tezuka comes to his show at Odakyū Department Store in Tokyo, carefully looks at each painting, and leaves saying, “They’re perfect.” Nakashima continues working with publishers looking for furusato (rural hometown) imagery in a mixed neo-classical and kawaii mode. In 1993, begins a set of paintings illustrating all fifty-four chapters of The Tale of Genji, which he finishes in 1998. In 2006, begins a cycle of fusuma (sliding door panel) paintings for Kiyomizudera Temple in Kyoto, which he finishes in 2010. In 2012, begins a set of cartoony and impressively violent Buddhist hell paintings for Rokudō chin’nōji Temple, also in Kyoto, which he gifts to the temple in 2015. In the past couple of years, his NHK and Kyoto temple connections have led to a spate of publications championing him as the preeminent artist of Japanese furusato.

These are Nakashima’s career highlights as described in two recent Bessatsu Taiyō catalogs, a 200-page hagiography, and prominent magazine articles about the artist and his work. Note that he is an artist whose main patrons have been domestic corporate clients, the government, department stores, and religious institutions – an influential and monied and decidedly conservative bloc. As you will discover below, Nakashima has been supported by one other elite patron, whose name has been strategically left out of every recent publication on the artist.

His work. It’s technically accomplished and often beautiful if you can see through the kitsch. What’s interesting about his nihonga paintings from an art historical perspective is the overt cartoon stylization of the figures, this years before Murakami Takashi’s Superflat and the subsequent Neo-Nihonga boom. While this can be attributed in large part to his early apprenticeship as a manga artist and his professional work in CM animation storyboarding, I wonder if Nakashima recognized the latent cartoonishness of early Meiji nihonga artists like Kano Hōgai and was consciously trying to reverse engineer a highbrow bridge between contemporary pop culture (manga) and neo-classical Japanese painting?

While most of his work features children, in the late 70s and 80s Nakashima created many paintings of thin young women, indicating another classical genre (bijinga) and another crossover influence in Hayashi Seiichi. Some even reference enka. The careful attention to background fields of flora, and the strong cutout quality of some of his figures, especially in recent work, suggest absorption of late Edo Rinpa aesthetics. I wonder if Kondoh Akino knew of his collaboration with poet Kaneko Misuzu (2005), with colorful images of pixie-sized girls nestled in flowers.

In Nakashima’s penchant for chubby children, one might again perceive an ex-cartoonist’s revision of modern Japanese art history: the airborne bubble baby of Hōgai’s Hibo Kannon (1888) animated in a squash-and-stretch contour line fashioned after Tezuka which was fashioned after Disney. The essential difference with Murakami and today’s Neo-Nihonga (other than stylistic differences) is that Nakashima’s subject matter is not ironic, not self-consciously excessive, not Pop, not reveling in consumer culture. Hence its inability to be appreciated as “contemporary art,” and its palatability to institutions like NHK, where the crassness of the world is buried under fronts of refinement, good behavior, consensus, and middlebrow taste.

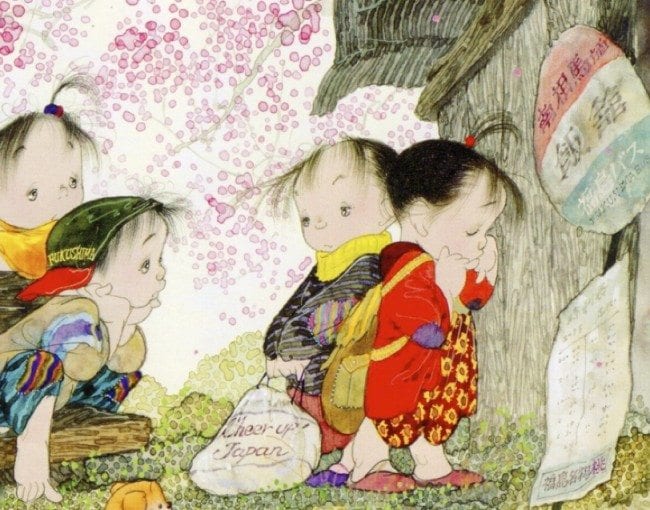

Much of Nakashima’s work since the 70s features pudgy little kids with hobbit-sized feet and wiggly caterpillar fingers (very Disney-esque), lying desultorily upon flower-flecked fields, hanging from trees (see first image above), or simply standing around looking lazy in an Indian Summer kind of way. There are also many images of komori (young female child-minders) walking across spring fields, standing under autumnal foliage, usually with their clothing and wisps of their hair tugged at by upstart gusts of wind, like an extended homage to Monet’s Woman with a Parasol (or related women-in-a-meadow paintings), which Nakashima reports falling in love with while in Paris in the early 70s, and which Miyazaki Hayao (also a master of middlebrow sentimentalism) productively exploited in his last films. Nakashima’s kids are typically dressed like bums, or more exactly like rich kids mimicking hippies, with floppy hats and loose hanging garments composed of brightly colored scraps (I think they call this boro), as if they’ve stopped at a Daikanyama boutique on their way to grandma’s house in the countryside. Furukawa Masuzō’s rusticated work for Garo (slacker fūten in ink landscapes) also comes to mind.

This was already a dated fantasy in the late 60s, this image of small Japanese kids out on their own in the countryside, as if their parents are too busy tending the fields to watch over them, as if they’ve been left to their own devices on the way back from collecting kindling or mushrooms in the forest. According to Nakashima, the imagery is rooted in his own childhood in Saga. “Everyday, I spent the day playing outside. Nearby were a mountain and a river. My memories of playing there is the starting point of my pictures.” But obviously, it’s a highly mediated representation, its codes derived from prewar dōyō and komoriuta and their adaptation in illustration for children’s books, and more immediately those songs and images adaptation in manga and illustration of the 60s. Nakashima’s work represents the mainstream culture that avant-gardists like Terayama Shūji and Hayashi Seiichi initially tried to subvert, but who, over the long term, probably did more to entrench furusato sentimentality than deconstruct it. It’s an aesthetic that matches NHK’s music programming (Nakashima’s second biggest client for the past three decades) perfectly. Oftentimes, Nakashima’s munchkins are carrying bags and knapsacks while waiting or resting. Sometimes the setting is travel, in images arranged around bus stops, which are simple wood shelters left over from the 50s and 60s, or more specifically from a timeless “Shōwa.” The mood is of simpler times as a child in the countryside back in the days before the Japanese village had become either a characterless suburban non-place or a ghost town hollowed out by outmigration. It is the Japanese version of Norman Rockwell’s Main Street, populated with the Japanese version of the Care Bears.

It’s culturally refined and technically accomplished kitsch, in other words. But there’s more. One of the watercolors at Maruzen showed a boy horsing around with a bag on his head, and on the bag it says in English “Keep Up Japan,” which I took to be the artist’s awkward translation of “ganbare nihon,” a slogan you heard over and over again after the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011. I asked the Maruzen salesman if this was the case. “Yes,” he responded, “Mr. Nakashima was deeply moved by the tragedies of the Great East Japan Earthquake, and so you will find special messages hiding in many of his recent works.” He pointed me to another watercolor, in which the “ganbare nihon” was really not hidden at all, plastered on multiple kids' shirts and hats and on a soccer ball. Knowing something about this artist that I have not yet shared with you, I already thought this disaster kitsch obnoxious. But when I picked up the accompanying catalogue, including ten times more work than what was in this little bookstore show, my blood began to boil.

Nakashima has made a number of images referring to Fukushima. It’s one thing to say “ganbare” for areas further north hit by the tsunami. Rebuilding and recovering emotionally is really all that the people in Iwate and Miyagi can do. But when a nuclear meltdown is thrown into the mix, and you are thus referring to a situation of massive corporate and government negligence with regards to both the disaster itself and the recovery efforts, and a situation in which people are fighting daily for compensation, to protect their personal health and that of their families, and to see that those responsible are brought to justice, what is the point of a supportive pat on the back in the form of a limited edition Hallmark card? The proper translation of “ganbare” in this situation is “sue the bastards” – but this, for reasons outlined below, is not something Nakashima is in a position to say. So it’s just, “get better soon.”

The Bus Stop on the Peak (Tōge no basu tei, 2013). Two girls, older and younger sister perhaps, stand at a shred of bus stop beneath a canopy of yellow foliage. The younger girl holds a bag that reads “Keep Up Japan.” Her puppy dog and her doll rest on a weathered wooden bench. The bus stop sign reads Futaba Peak, Bound for Sōma, Fukushima Transportation. Sōma is a district on the coast, north of the Daiichi facility. It was hit by both the tsunami and the meltdown. Futaba is a large district (856 sq km), and as home to the Daiichi reactors, the one most heavily hit by the meltdown. Almost the entire district (more than 70,000 people) was evacuated progressively in the days after the accident. Today about one-tenth of Futaba’s citizens have returned, after the government recently reopened limited portions of the area to inhabitation, much to the anger of Futaba citizens, who recognize the reopening as the government’s attempt to deny their “rights of evacuation” (hinan no kenri, their right to compensation and relocation) and pretend that the meltdown was much less serious than it actually was for the sake of TEPCO’s financial health, the Japanese nuclear industry’s survival, and the ability to say that all is well by the time of the 2020 Olympics. Most of Futaba district today is a weed-infested ghost town. These girls will be waiting a long time for that bus to arrive.

A New Wind (Atarashii kaze, 2011). An artist with an extremely limited range when it comes to subject matter and composition, Nakashima has been producing such bus scenes since at least the early 90s. Even a meltdown has not persuaded him of the wisdom of change. Here’s another one, this time with an entire gaggle of kids waiting. Many have accessories inscribed with variants on the English of “ganbare nihon,” and one wears a ball cap that says “Fukushima.” The bus stop reads Iitatemura, Bound for Minami Sōma, Fukushima Bus.

Iitatemura is located in Sōma, the district north of Futaba. A small agricultural community, it was added to the registry of The Most Beautiful Villages in Japan in 2010. Then came the meltdown. Iitatemura was located beyond the original 30 km radiation exclusion zone. But due to shifting wind patterns, the entire population of 6000 was evacuated on May 30, 2011. This is probably not the “new wind” of Nakashima’s title. Because of the mayor’s reluctance to make public alarmingly high Geiger counter measurements, evacuation was delayed, with the result that Iitatemura residents were some of the highest irradiated in Fukushima.

It’s a weird image, not least in how it crosses past and present. The kids wear clothes meant to evoke the early postwar years, but which are inscribed with messages addressed to the post-2011 present. They wait at a bus stop that is modeled on those from simpler times, but in an era that is cripplingly complex. One can easily criticize Nakashima for trying to use nostalgia as a superficial band-aid on a painful and exceedingly infuriating political and legal situation. Presumably Nakashima intends for the viewer to travel back in time through his images, and gain solace and strength in fantasy images of their own era of innocence. But what’s really creepy is how this and other images are temporally structured such that it’s almost as if the children of the early postwar years (Nakashima’s generation) are prophesizing things to come. This, we will see, considering Nakashima’s career and his primary audience, is extremely disingenuous.

Bullfrog (Ushigaeru, 2012). Another Iitatemura image. A boy and a girl stand atop a big black bag half curious and half afraid of a big-eyed bullfrog that has hopped their way. On the bag is a white label that reads “Cheer Up Fukushima” and white text that reads “Disaster Prevention” and under it “Iitatemura Youth Association.” This bag resembles what is now often referred to in Japan as “furekon baggu,” literally “flexible container bag,” or what they call in English “flexible intermediate bulk containers” or FIBC. Made of thick woven plastic, furekon bags are designed for hauling soil and grains and are often used as sandbags for creating flood barriers. In Japan today they are associated mainly with decontamination efforts, as containers for storing contaminated soil removed from areas inside and around the exclusion zone. Former farmlands in Futaba, Sōma, and northern Iwaki have been converted into “temporary storage sites” (kari okiba) for this low-level radioactive waste, creating eerie images of hundreds and thousands of these bags piled ten feet high and hundreds of feet deep, forming black, blue, or green (the last the color of the nets thrown atop them to keep crows away) sarcophagi across the Fukushima landscape.

Who knows what Nakashima imagined is in that furekon bag on which those two children stand. But it looks like soil. I am thinking, especially because it’s open, they should probably be playing somewhere else.

Children are the last category of human that should be in contaminated areas like Iitatemura or Futaba. Their bodies are the most susceptible to radiation. In the summer of 2015, studies showed increased rates of thyroid abnormalities amongst children who had lived near Fukushima Daiichi at the time of the meltdown. The government and some scientists have attributed this to overscreening and overdiagnosis. Recently, in March 2016, the Japanese government announced that it intends to declare most of Iitatemura safe for living in 2017, with schools ready to open in April. While the maximum exposure limit for Japanese citizens is set at 1 msv per year, an exception has been made for school facilities inside Fukushima prefecture so that estimated exposures (based on ground and air surveys) can be up to 20 msv per year. (The exclusion zone around Chernobyl is set at 5 msv per year). Naturally, this has angered area parents and activists intensely. It’s one thing if the elderly wish to live out their final years in the comfort of their contaminated homes, but quite another to allow children to play in schoolyards only superficially decontaminated by removing a few centimeters of soil.

Preempting such outcry, the Fukushima prefectural government is creating multiple Environmental Educational Centers (Kankyō sōzō sentaa) ostensibly dedicated to educating citizens about radiation and helping with radiation monitoring and decontamination efforts. Activists fear it will become a center of strategic misinformation, since it will operate under a government with a track record of dissimulation and in collaboration with the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency). As a taste of things to come, in local libraries, government offices, and convenience stories, residents can today pick up copies of Eggplant’s Doubts (Nasubi no gimon), a manga produced by the Ministry of the Environment and issued by an outreach organization called the Decontamination Plaza (Josen puraza). Its goal, once again, is to educate people about the science and dangers of radiation. The eponymous Eggplant, modeled on a local TV personality whose head looks like an elongated aubergine, asks scientific and medical experts their opinion on various aspects of the matter. At a symposium I attended recently in Iwaki, activist Mutoh Ruiko (coordinating member of the group, Complainants for Criminal Prosecution of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster) described the content as “90 percent accurate, but 10 percent false.” As an example, she singled out a passage in which a doctor recognizes the genetic damages caused by radiation, but then explains that DNA self-repairs after a few hours.

Nakashima’s work is not targeted at kids. Though children populate his images, his main audience is senior citizens. This is the sense I got at the Maruzen show, with the old ladies being targeted most aggressively by salesmen. But it is also stated outright in some of the texts published recently in support of his work.

Most of post-disaster images discussed above have appeared as cover illustrations for Late Night Radio (Rajio shin’ya bin), a monthly magazine that supports a program of oldies songs of the same name that is produced by NHK. Its nightly listenership is reportedly around 200,000, the vast majority of whom are seniors. The magazine’s circulation is around 140,000, and it too is mostly consumed by seniors. Nakashima has been drawing the covers since the first issue in 1996. As noted above in the officially-approved rundown of his achievements, he has been hired by NHK on many other occasions since 1982. Thus, while his work can be described generally as kawaii and sometimes Pop-y, it is important not to mistake that to mean that he draws for little kids or frilly girls, and instead recognize that Nakashima’s work belongs to a category that we might call Silver Art, a main feature of which would have to be Japan’s aging baby boomers’ nostalgia for rural furusato. But as Nozaki Hiroyuki, head producer of NHK’s Late Night Radio, explains in a short text on Nakashima’s work, there’s more to it than that.

Nozaki says that the commonly held view at NHK about why Nakashima’s work appeals so much to the elderly is that his images are suffused with “nostalgia” (kyōshū) and a “soothing” (yasuragi) quality. He thinks, however, that seeing things that way is condescending to a generation whose life experiences have contained too many hardships for their relationship to images evocative of the past to be so simply therapeutic. We need, he suggests (without putting it this way), to understand what kawaii might mean to old people. Seniors see themselves in Nakashima’s children, not, Nozaki hypothesizes, as idealized images of themselves in the past, but rather as sympathetic mirrors of themselves in the present. “The children that Nakashima draws might look like they are having a good time together, but what really leaves an impression are those works that show them in seemingly trying conditions. They are battered by the wind, they get wet in the rain, they look cold buried in the snow. They vacantly avert their eyes in the face of such conditions. What we can see in their expressions is worry (fuankan) and powerlessness (muryokukan).”

He continues: “Such sentiments correspond to most elderly people’s reality. They sincerely see themselves in the children in these pictures. The children are powerless to do anything about the situation they find themselves in. Thus they also worry about what will come just ahead. It is the same for the elderly, except that for children it’s ‘someday I will (might be) able to change things’ while for the elderly it’s ‘I will (probably) never again have the power to change anything.’ There is a metaphor – the fire of life – that people use in reference to Nakashima’s work. If a person’s age is the horizontal axis, and the magnitude of the fire the vertical axis, then as you mature the flame of the fire grows stronger, and when you get old it fades. Considering just the size and weakness of the flame, the elderly and children are the same. If a strong wind blows, either will be snuffed out all too easily.”

But what to do with the fact that Nakashima’s images are invariably set in the countryside? That can probably be chalked up to the art historical (nihonga) and popular cultural (dōyō and related media) context I sketched out above. Sociological is the last thing Nakashima’s work is, yet in an age in which the Japanese countryside has suffered from serial decades of depopulation, and have become essentially sprawling old folks homes – a common lament is that there’s no descendants around anymore to tend the family grave – Nakashima’s imagery appears as an extended fantasy of rural rejuvenation, in which the geriatric hopelessness that Nozaki describes is replaced with youthful hopefulness for a brighter and better tomorrow. The “ganbare nihon” pep talk imbedded in Nakashima’s images thus seems directed less at the disaster and more at the suffering Japanese countryside in general, which Nakashima has represented by not representing it for decades.

As for the Fukushima works, in some ways it is appropriate that they are different from Nakashima’s previous works. It has been argued, by scholars like Kainuma Hiroshi, that the meltdown only accelerated an irreversible, decades-long process of depopulation in the area. Yet the evacuation has enabled an interesting reinterpretation of the aging countryside in art, film, and photography. As mentioned above, many elderly in the exclusion area have wished to live out their last years in the comfort of their homes despite the radiation, knowing that they will die of old age before they will die of radiation. A number of documentary and fictional films (most famously, Sono Shion’s The Land of Hope, 2012), as well as photography collections, have taken this phenomenon and used it to create a picture in which the older dystopian image of the countryside as a place where the elderly are left to die becomes instead a place where they choose to live. The rural ghost town is turned into a kind geriatric utopia, where the elderly not only get to live out their lives in the (compromised) manner they wish but also become emergency life-givers to the community. By living in the abandoned village, they offer proof of life even though the village has officially been pronounced dead. The ease with which Nakashima has incorporated “ganbare nihon” and Fukushima motifs suggests that the furusato as geriatric utopia was perhaps latent in his imagery all along.

However, there is good reason to believe that Nakashima also had personal motivations for peppering his furusato with melancholic Fukushima references and post-disaster pep talk. The time has come to tell you how I knew about Nakashima’s work before going to Maruzen, and why I find his recent work gross on more than aesthetic grounds.

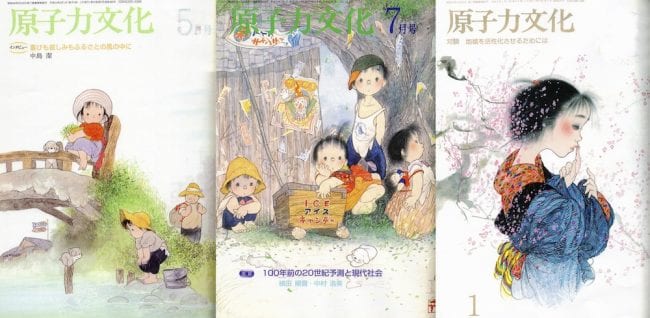

You won’t find this piece of information in the catalogue published to accompany the Maruzen exhibition, nor in any of the many other catalogues and texts on Nakashima’s work issued in recent years. In lists of his achievements, they have seen fit to omit the fact that for more than forty years, from its first issue in January 1970 until June 2011 – exactly 500 issues, including three after the Fukushima meltdown – Nakashima drew the covers for Nuclear Culture (Genshiryoku bunka), the leading PR magazine published by JAERO (Japan Atomic Energy Relations Organization, Nihon genshiryoku bunka shinkō zaidan, literally “Japan Atomic Energy Cultural Promotion Foundation”). An agency set up by the government in 1965 to promote the “peaceful use” of the atom, JAERO was one of the most aggressive promoters of nuclear power in Japan through pamphlets, manga, magazines, newspaper ads, films, science centers, events around “Nuclear Energy Day” (October 26), and essay writing contests amongst school students, all of which were ultimately paid for by Japanese citizens through taxes and tariffs on their electricity bills. The organization was hated, despised, and a little bit feared by antinuclear groups across the country, especially in how it targeted children. For those, like Nakashima, who have actively contributed to this and related programs, antinuclear voices have unkind names like “genpatsu bunkajin” (nuclear power literati) and “goyō sakka” (lapdog artist/writer), the latter derived from the title for those who served the shogunate.

According to JAERO, Nuclear Culture had an opening print run of 15,000. This had increased to 40,000 by the mid 90s. It’s “Nuclear Energy Day” special issues had a print run of 50,000. Like much pro-nuclear propaganda of its day, the magazine was a tour de force of strategic half-truths passing themselves off as utopian promise and expertise opinion. Flush with money, it was able to corral major cultural figures to create work and submit to interviews that flattered the industry. Amongst them were cartoonists Tezuka Osamu, Akatsuka Fujio, Tominaga Ichirō, Fujiko Fujio, and (staunchest of them all) Matsumoto Leiji. Also architect Kurokawa Kishō, illustrator Manabe Hiroshi, and science fiction writers Komatsu Sakyō and Hoshi Shin’ichi. On a future occasion, I will dive into the pages of Nuclear Culture to look at how science fiction and kawaii were exploited by JAERO between the 70s and 90s, and how some of the baby boomer generation’s favorite manga artists and illustrators embarrassed themselves for the sake of nuclear money. Here let me reflect on a less obvious but nonetheless key dimension of the magazine’s discursive campaign, and that is its attempt to convince Japanese that rural furusato and industrial development were a match made in heaven rather than – as most people thought, especially antinuclear parties – natural born enemies. After all, one has to explain why the sentimental, pastoral Nakashima Kiyoshi was kept on JAERO’s payroll for more than forty years. He also contributed spot illustrations to most issues, and for many years his cover paintings were reproduced in annual Nuclear Culture calendars. In a world that you’d expect to be represented by gleaming control rooms, happy air-conditioned families, and sparkling night skylines, it was Nakashima’s unplugged country kiddies that JAERO chose as its poster children.

In 1970, the first year of Nuclear Culture, Nakashima’s covers show children gazing at the stars, tending cows, looking at flowers, and generally enjoying the wonders of nature. They are done in a feathery children’s book style unlike the manga-nihonga mode that became his signature. In late 1971, he dispensed with human figures, and drew pointillist landscapes with sea-bottom civilizations, flying helicopter pods, and other futuristic visions fluttering in the margins. Were it not for the fields of flowers, it would be hard to recognize these as Nakashima images. The nursery room quality of these covers might give the impression that Nuclear Culture was meant for children. Indeed, the texts inside are simple enough to be read by middle-schoolers, and there are readers’ letters from the same. Yet the covers seem too delicate and infantile for the average robot and sports loving boy, or the average heart-pounding girl. As even the magazine’s futurism has a strongly nostalgic flavor – rooted, like Nakashima’s 1972 covers, in 50s fantasy – I presume that even here Nakashima’s handiwork was recruited for its potential appeal to baby boomer adults, at this juncture on the cusp of parenthood.

After Nakashima’s show at the Mitsukoshi-Etoile Art Gallery in Paris (May 2002) and again after receiving the Kiyomizudera commission (February 2010), Nuclear Culture featured multi-page interviews with the artist honoring his achievements. In neither is nuclear or anything remotely related discussed. They’re all about art, his life, and why people swoon over his pictures. In fact, it’s hard to find any commentary on nuclear by Nakashima anywhere, even before he had reason to run and hide. But I do know of one sample, a short essay by Nakashima for an in-house publication celebrating JAERO’s twenty-fifth anniversary, published in 1994. It is a beautiful demonstration of how rural nostalgia could be interpreted (and contorted) in the name of developmentalism.

It opens with Nakashima returning to his childhood home in Saga, and waxing nostalgically on the soothing yet fragile qualities of rural Japan, which are such a therapeutic relief to him after so many years in the alienating city. Then, four paragraphs in, he shifts gears.

However, as the months and years flow by, even my hometown has sustained injuries. Upon my aunt’s farm fields where I played as a child, an expressway. The hills where the little birds cried have changed their shape, the river where the fish leaped has been straightened and lost its character, the road on which I ran to school with sleepy eyes is now a thoroughfare for dump trucks that threaten to crush the houses on each side, and children hide green hair beneath white helmets.

As I wandered through my hometown, I had the following thoughts. Time never stops, not even for a second. All things have a life. They continuously change while progressing forward one step at a time. Humankind stood up on two feet, took fire in both hands, and today has spread its wings of ambition in the direction of outer space. We have been challenged by disasters and illnesses, and reside within a civilization and culture that are already confounding in their scale, and yet they march ahead.

I got on the night train and headed back to the city. The houses outside the window were a light inky black, glowing within from a softly burning light. Around each light snuggles a family, caring for one another with love and affection, from parent to child, and then on the next generation, and so forth forever, proceeding ahead with dreams and hopes burning, just as nature’s shape never stops changing.

Today we have nuclear energy by our side. Like those families snuggling around the lights, today and for all eternity, we should go on living with love and affection for nature and all the world’s myriad things.

Nuclear power at the heart of the traditional nuclear family, to be loved and embraced like a new family member. It’s hard to find exact correlates to Nakashima’s nuclear kotatsu (heated family room table) here within the pages of Nuclear Culture. One might cite essays and cartoon diagrams that demonstrate how nuclear power can revolutionize rural homes and agriculture, but they typically lack any nostalgic dimension – nuclear countryside and nuclear homes, but not quite nuclear furusato. It also recalls the newspaper ads JAERO was funding in the mid 70s (discussed last time), featuring romantic imagery and beseeching the Japanese public to care for nuclear power like parents for a vulnerable but special child. For example, in 1976: “Rather than looking on nuclear energy with apprehension, we must actively support this ‘energy’ that represents the ultimate achievement of human intelligence, and contributes to its further growth. Nuclear power is ‘youth’ itself. And that is why each and every one of us must trust in it, look after it, and help it to grow.” But here too, the geographical dimension is missing.

As for that geographical dimension, consider Nuclear Culture’s occasional series “Bunka fūdoki.” The title might be translated as “Annals of Cultural Geography,” though the Japanese is not so academic sounding. The series looked at locales where nuclear power stations were being built, were about to built, or where the industry thought they should be built, with a focus on their cultural traditions, histories of industry and farming, and geography. Whether they are set in Tsuruga, Onagawa, Hamaoka, or the Noto Peninsula, inevitably the articles follow the same pattern. They begin with a few lines outlining history and landscape, then a statement that the area’s remoteness has left it cut off from nearby development is paired with a poem from the Manyōshu and/or by Bashō praising the beauty of the area. Then they go into more detail regarding local history, religious festivals, animal habitats, rare local flora, and notable geographical features. Further reminders are dropped in that what makes the area romantic is also makes it backwards – the oft-noted paradox of furusato. Descriptions of public works helping people in their struggle against nature are worked in. Life for farmers has been made much easier by the introduction of modern technology, while things like highways have improved the quality of life by better linking the traditional fishing and farming village to the culture and consumers of the cities. And then, often when you’re not expecting it, the local nuclear power plant is introduced, as a natural extension of rural modernization, exceptional not because of the magical nature of what goes on inside the reactors, but because of the unprecedented largesse nuclear plants bring in terms of roads, bridges, and jobs.

As if the nuclear industry’s primary motivation for aggressive expansion was to improve rural people’s lives, harmony and mutual aid are recurrent themes in “Annals of Cultural Geography.” In the entry about the Tsuruga Peninsula (November 1970), for example, “the fire of the atom” is credited with finally bringing an “isolated island” into connection with the rest of the country. While the area has been blessed with rich fishing and beautiful beaches and sea, life was never easy for the average resident, until the plants brought roads to the area, which brought tourists, which brought income to the struggling fishermen, which enabled them to buy “color television sets and microwaves.” For the bridge that connects the Mihama plant with the main road, the industry was thoughtful enough to “call in a specialist to chose the right colors to paint the bridge, and site it so that the beautiful view would not be lost.” The domes of the containment buildings themselves present a pleasing view from the white sands beach on the opposite shore. “On August 8 [1970], the day KEPCO first sent the light of atoms to Osaka Expo, visitors to the beach swam while gazing upon the plant, enjoyed fishing, and visited the PR center in their swimsuits. What a picture of health this was.” Given nuclear plants’ universal siting on the coast, similar scenes could easily be created for most any locale, like Hamaoka (August 1970): “With the sound of sara-sara sara-sara [wind blowing across the sand dunes] audible, and the beautiful windswept ripples across the sand in view, the Hamaoka Nuclear Power Station was constructed with a concern for harmony with nature.”

Never mind that, in many of these places, farmers and fishermen were fighting tooth and nail against the construction of nuclear plants and the underhand methods that had been used by utilities and the government to acquire land. In late 1970, in one of the earliest major magazine articles on regional antinuclear power movements, Ōishi Yūji surveyed the situation in Tsuruga, Hamaoka, and Kashiwazaki (designated site of what was to be then the world’s biggest nuclear power complex) for the popular left-leaning weekly Asahi Journal. “Nuclear power plants are the hidden fortresses (kakushi toride) of 70s Japan,” begins the article, using a term that would have probably evoked for contemporary readers Kurosawa Akira’s 1958 film. “This fortress has neither embrasures nor a drawbridge. However, the guards protecting its gates greet you with their fists together like soldiers. The technicians wear on their uniforms neither military medals or insignia of rank, but rather film badges that tell whether or not you have been exposed to radiation. Inside the fortress is administrative society (kanri shakai) itself, though its inhabitants are late twentieth century fire worshippers who pray to a god housed in a temple made of two layers of steel and concrete.” Like Nuclear Culture, the opposition could also allegorize the nuclearized furusato through antiquated historical tropes.

In contrast to Nuclear Culture’s travel writer’s approach to fantasizing the harmony of modernity and tradition in the Japanese countryside, people with sympathies for the antinuclear position tended to see the tensions created by the arrival of nuclear power plants through the history of peasant rebellions. “Looking at previous examples [of antinuclear movements],” writes Ōishi, peppering his non-fictional fable with terms taken from the Sengoku (Warring States) Period of the 17th century, “it’s rare for rebellions to succeed. The Empire’s mercenaries are sent in to break up the power of the peasant uprising (ikki). A rat inevitably rears his head within the peasant army (domingun) and tries to buy off the struggle with money. The leader continues screaming for battle to the death, yet finds himself isolated amongst people who were only yesterday still his allies. He looks around, and discovers that the ‘people’s sea’ that once teamed with guerilla fish has all but dried up.”

Presumably, the oft-made comparison between the Sanrizuka struggle (against Narita Airport) and Edo period peasant revolts helped Ōishi in fashioning this decidedly anti-furusato rendition of the nuclearizing countryside. Later in the early 70s, photographs taken in Kashiwazaki and Onagawa by Higuchi Kenji and Hanabusa Eizō show farmers and fishermen at antinuclear protests carrying farming implements and mushiro-bata (straw mat banners) inscribed calligraphically with angry slogans, looking almost like they just walked out of one of Shirato Sanpei’s manga. They are, at any rate, images inflecting a tradition of leftwing “people’s art” and people’s protest rather than the passive furusato of contemporary mass entertainment. In the realm of art, one might most effectively juxtapose Nakashima’s imagery with a mural-sized painting completed in 1981 by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, painters of the famous Hiroshima Panels (Genbaku no zu, 1950-82), showing fiery protests against nuclear power in the Noto Peninsula next to protests in Sanrizuka and Minamata. The furusato was aflame with industrial development.

One can find reference to protests in Nuclear Culture’s “Annals of Cultural Geography,” but it is oblique and condescending. Every mention that is made of nuclear plants providing a lifeline for economically suffering rural communities is, in effect, a reiteration of what was the primary pronuclear stance within village debates. The opposition’s response that development was dangerous and not in the region’s long-term interest is, when recognized at all in these articles (which is rare), neutralized through historical trivia. For example, in the article on Hamaoka, in lieu of recognizing oppositional voices in the present, the writer recounts Meiji period fishermen’s opposition to the Omaezaki Lighthouse (erected in 1874). They feared that the bright illumination would scare away fish. Once the fishermen began appreciate the lighthouse for the ease of sea navigation it provided and the income it brought in through tourism, they saw the errors of their ways. Ergo (reading between the lines), antinuclear protests are just another kneejerk reaction to modernization by goodhearted but tradition-bound people, whose enlightenment and acceptance of industrial development go hand in hand. Such an attitude and logic is common to many forms of colonialism.

Hence the need for “nuclear culture,” which JAERO described as a form of “PA” (Japanese business jargon meaning “gaining Public Acceptance”), but was essentially a civilization and enlightenment program tasked with breeding out the irrational superstitions of the anti-modernists and radiophobes. It was a propaganda campaign to gain new supporters, but also an aestheticized façade to hide the fact that the Japanese nuclear industry achieved its greatest successes in securing public consent through the non-cultural means of political bribes, buying land, flooding the countryside with pork barrel, and promises (absolute safety, the nuclear fuel cycle) that it knew it might not be able to keep – in other words, through lies, money, and force. It was this campaign of false advertising that Nakashima’s furusato imagery was recruited to support. His covers projected a paternalistic industry that cared about the future (children) and cared about the past (furusato) through a public commitment to “culture.” They presented as benevolent and benign an industry that was recklessly aggressive.

It would be one thing if Nakashima had drawn for Nuclear Culture once or twice, or even a dozen times in the days before it was widely recognized that nuclear power was an expensive, dangerous, plutocracy-breeding, kicking-the-can-down-the-road industry. But he continued to do so after exposés were published about exploited nuclear janitorial labor in the late 70s, after Three Mile Island in 1979, after the cover-up of leaks at Tsuruga were exposed in 1981, after Chernobyl in 1986, after protests against the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant increased in the 90s, after the Monju sodium leak in 1995, and after the JCO criticality accident in Tokaimura in 1999. Though his imagery was trapped in an idealized past, Nakashima himself could not have been so oblivious to know nothing about his client’s running record of infamy, which was slathered all over the newspapers for anyone with eyes to read. Given the handsome sums the nuclear industry is known to have paid its supporters, Nakashima either benefited handsomely for his belief in nuclear power, or chose profit over integrity.

Either way, short of making a clean breast of his past associations and reflecting on them verbally or visually, Nakashima has zero right to make work about Fukushima. Clearly he recognizes the stain. How else to interpret his choice to leave out from his biography one yen-packed pillar of his career as a successful commercial artist? How to explain the fact that, after the June 2011 issue of Nuclear Culture, his artwork disappears from the magazine? Are we to believe the editorial note in the same issue stating that, “for health reasons (kenkōjō no riyū), the artist Nakashima Kiyoshi will no longer be able to able to draw the covers of our magazine”? Did he have to be convinced to stay on to the 500th issue, three months into the disaster, or did his agent have to convince him the wisdom of parting ways? Seeing how subsequent issues of Nuclear Culture and the Japanese nuclear industry have been desperate to project the image of minimal damage and minimal necessity for rethinking nuclear policy, I cannot imagine JAERO wanted Nakashima to leave.

Do you now see how gross, and not just tacky, Nakashima’s recent Fukushima images are, reflecting melancholically as they do on the disaster and saying to the evacuees, “Chin up!” while the artist does his best to bury the part he played in the expansion of a reckless, dissimulating, furusato-killing industry?

And the story continues . . .

Last year, Nakashima finished a series of Buddhist hell pictures for Rokudō chin’nōji temple in Kyoto. The paintings, which took him four years to finish, are quite fantastic and graphic despite their cuteness, with sinners tortured and dismembered by underworld ogres in delightful detail. The images are based on varieties of hell and sinners’ punishment as depicted in medieval texts and paintings. For example, murderers are diced and pulverized like food. Drunkards are forced to drink molten copper. Adulterers and other people (men) who have surrendered to the desire of the flesh are made to climb bladed trees in pursuit of beautiful women. Heretics are skewered through the anus to the mouth. Iconoclasts receive all of the above, plus are cooked by the breath of a poisonous, fire-breathing serpent. “The times have changed, and hell has lost its meaning for modern people, so I think it’s important to find ways to approach it anew. That’s why I’m very happy that Nakashima sensei decided to create a set of hell pictures,” commented a priest at the temple pleased with the interest Nakashima’s pictures were extracting from children visitors. Yes, even the Japanese religious establishment appreciates the power of manga/anime aesthetics.

In a recent catalogue of his work published by Bessatsu Taiyō, Nakashima recalls his motivations for wanting to depict hell. He felt something lacking, he says, after completing his cycle of fusuma-e for Kiyomizudera in 2011. The goal of the project was representing “a beautiful soul” (kireina kokoro), and he gave his all to see it successfully executed. “But hadn’t I failed in expressing the hidden emotions inside of me? The world is filled with human relations ruled by desire [a bad trait in Buddhism], and then there was the giant disaster of 2011. There are also so many bad things on the news. What I then thought was that I would represent ‘anger’ [also a sin in Buddhism]. You cannot say you’ve represented everything if you’ve only shown the good. You also have to show the opposite.” In a hagiography published to coincide with the hell cycle’s completion, he adds, “I think balance is important, whether you are a painter, a musician, or a novelist. A painter who paints everything but anger is not balanced. By only expressing good things or things that people want to hear, or avoiding saying things that people won’t like, I realized I had been living a lie as an artist. So I thought now was the time to make pictures out of anger, pictures that really captured anger.”

This hagiography, A Painter: Nakashima Kiyoshi Hell Pictures 1000 Days (Egaki: Nakashima Kiyoshi jigoku-e 1000 nichi, 2015), written by one Nishidokoro Masamachi and published by a for-hire editing and publishing company named H & I (Harmony & Independence), is the kind of book I have only come across in art history when looking for information on nationally beloved nihonga artists, people like Kayama Matazō, Higashiyama Kai, and Hirayama Ikuo. Significantly, in contemporary art, only Murakami Takashi (whose doctorate in fine arts is in nihonga) marshals greater sycophancy. Neo-classicism might have mass appeal in Japan, but it depends on conservative power and elite money for its institutional legitimacy, and often uses that leverage to attract educated, eloquent, but helplessly star-struck writers who are more than happy to exchange their integrity for the privilege of access to high culture’s inner circles. The situation is not wholly unlike the nuclear industry with its PR mercenaries, with Nakashima a perfect example of how these two worlds of power can intersect in Japan. Nishidokoro’s book on Nakashima is particularly shameless, as the above quote – “I realized I had been living a lie as an artist” – should already indicate. When it’s not shedding stage tears over the artist’s personal struggles or fatuously praising his genius, it’s trying to make him seem a man reborn and galvanized by the 2011 disaster. Yet it makes no mention of Nuclear Culture. And without that, Nakashima’s heartfelt promises of becoming a truth-teller during this last phase of his career means absolutely nothing.

All the more irksome, then, that ethical questions are front and center when Nishidokoro discusses Nakashima’s hell paintings. Those afflicted by the disaster are described at various points as having “experienced hell” – vague and figurative enough. From the book’s first pages, Nishidokoro expresses concern with the appropriateness of showing such images to the disaster victims. For him, the issue seems to be that the paintings might be too violent and thus too disturbing for them, having been through so much already. But when he poses the question to Nakashima, the artist gives a bizarre, religiously oriented response. “The people who were killed by the disaster will definitely not go to hell. In my hell pictures, no such people go to hell. Everyone has survived. But the babies, parents, and friends who were killed . . . none of them will go to hell. That’s what I want to communicate. Those people, I want to save them.” As if (and Nishidokoro points this out too) the fate of their souls were in the earthly artist’s hands. An artist’s egomania taking religious expression? Or a sense of responsibility stemming from something else?

Many times while Nakashima was working on the paintings, we are told, he felt like he didn’t have the courage to finish. He worried that there would be no one who cared about these paintings. What kept him going? “The feelings of the victims of the disaster,” Nakashima says. Apparently he felt most keenly about those afflicted by the meltdown. “It’s not like Nakashima had not done anything for the disaster areas before this,” explains Nishidokoro, in reference to the “Keep Up” series. He relates a touching episode of “an older woman crying while standing before A New Wind and Bullfrog” when the two Iitatemura-inspired paintings (reproduced above) were exhibited in Fukushima, accompanying the Kiyomizudera fusuma-e’s tour of Japan in 2013.

“But Nakashima was still not satisfied,” we are told. “When he began making the hell pictures, he did so thinking that they might be of some help to the people of the disaster area. This was only instinct. Nakashima has always worked upon instinct, upon flashes of inspiration. . . . As he created the hell pictures, then he began to see what their significance was. He wanted the people of the disaster area to use them to vent their anger upon. Why must our children and our grandchildren have their lives taken away from them before their dreams come true? Why must we lose our husbands and wives, the homes our ancestors protected for so many generations? We can’t grow produce in our fields, our sea has been filthied. How much longer must we live in temporary settlements . . ?” And just when you think the hypocrisy couldn’t tower any higher, Nishidokoro adds, “Who those hell pictures are angry at is not the victims of the disaster, but rather those who made the victims angry. That’s why they [Nakashima and the victims?] can get angry together.”

Everything, tell us everything, but the detail that matters. This would be the place in the text that Nakashima and his hack biographer, had either of them an ounce of integrity, at least mention the artist’s own contributions to Japan’s nuclear culture. But no, that doesn’t happen. One has to flip back a few pages for a moment of critical self-reflection. It’s painful for Nakashima, we are told. But the occasion is utterly mundane. In the 90s, Nakashima split from his wife, leaving her and their three children while he decamped to a quiet studio overlooking the sea in Atami and life with another woman. “My past returned to me [as I painted the hell pictures]. There were multiple me’s in that hell. There’s one here, and also one over there. That man climbing the tree in pursuit of the beautiful woman, that’s also me. The act of painting hell pictures was a process of being forced to confront the things I’ve done in the past. If you were ask me to say something about my divorce, about having left my children to bear the same sufferings I bore when I was young [his father immediately remarried after his mother’s premature death from cancer], I’d be at a loss of words. What I can do is paint the sufferings that are bound to happen in the course of life. Paint it sincerely, paint it with everything that I have. And furiously paint a hell that forces me to confront myself completely. As an artist, that is the only kind of answer I can offer.”

How, when the artist feels so deeply, when he has visibly suffered so much, when he has been so open with us – how then could we even think of questioning him? It’s not my place to psychoanalyze an artist I have never met and whose work I have only recently gotten to know. But tell me this doesn’t read like a textbook case of evasion and strategic remorse, the soul-searching tone an elaborate smokescreen. Yes, he goes as far as putting himself in the picture, as party to the sins of the world. But not for the one that matters. And in this, Nakashima seems to have taken the ethics of his former friends in the “nuclear village” for his own. As Abe Shinzō has used “the lessons of the Fukushima disaster” to globally promote the Japanese nuclear industry as the world's most sensitive to safety issues, so the artist who most reliably stood by the industry’s side is now appointed with the task of helping to heal its victims’ wounds. And where things don’t add up, use PR to obscure the gaps.

Wait, before you go. I think I see another Nakashima. Not the lascivious one in the trees. Look, amongst the liars and deceivers and the careless speakers, who are punished by having their tongues pulled out of their heads or stretched and nailed into the ground. There he is, amongst the other nuclear literati who don’t have the courage to come clean and openly face the world they helped create.

Japanese title: ふるさと発、地獄行き:中島潔と『原子力文化』

Related articles:

"Pro-Nuclear Manga: The Seventies and Eighties" (February 2016).

"Manga 3.11: The Tsunami and the Japanese Publishing Industry" (August 2011).