Every comics fan has one: an obscure work that sneaks up and enthralls you, until you’re overcome with a desire to fiercely defend it—or recommend it—to anyone within earshot. I admit: I’ve fallen victim to this type of comics monomania several times in my life,thanks to works such as Justin Green’s The Sign Game, Jimmy Frise’s Birdseye Center, and the original run of Collier’s by the great David Collier. All works of singular, quirky genius that I maintain deserve much more adoration.

But when it comes to great overlooked comics there are few greater—or more woefully overlooked—than Bus Griffith’s Now You’re Logging. First published in 1978, it’s worth it for a couple of reasons: 1) it’s one of Canada’s first real graphic novels, and 2) it’s one of the few graphic novels to portray the logging industry—or any industry for that matter—in such a thoughtful and considerate manner.

But when it comes to great overlooked comics there are few greater—or more woefully overlooked—than Bus Griffith’s Now You’re Logging. First published in 1978, it’s worth it for a couple of reasons: 1) it’s one of Canada’s first real graphic novels, and 2) it’s one of the few graphic novels to portray the logging industry—or any industry for that matter—in such a thoughtful and considerate manner.

Taking its name from early 20th Century logging slang, Now You’re Logging is an honest-to-goodness, roll-up-your-sleeves, working-man of a comic. Which shouldn’t come as a surprise given its author, Bus Griffiths: a career outdoorsman and self-taught cartoonist from British Columbia who relied on logging and fishing to pay the bills that comics couldn’t.

A burly gem of a book, Griffiths’ paean to life in the woods manages to summon the working-stiff spirit of American Splendor and The Sign Game while packing an unmistakable—and improbable—resemblance to the art of Howard Cruse and the infamous homoerotic artist Tom of Finland. (I think my friend and fellow comics writer Bryan Munn summed this up nicely when he called Griffiths “a sort of porno woodsman icon.” And I suppose the title of the book doesn’t help much in this regard.)

But despite this book’s ample bizarro charm and historical relevance, it’s somehow managed to fly under the comics radar for much of its 33-year existence. Aside from a 1996 Comics Journal interview with Griffiths, the book has received remarkably little in the way of critical appreciation. It’s as if the comics world greeted it politely, then simply abandoned it for more interesting party guests. As a result, it has become increasingly scarce: out-of-print for more than 20 years, original hardcovers now typically fetch $250 price-tags. A combination of these factors have resulted in Griffith’s life’s work being summarily swept into history’s dustbin; unfairly forsaken by time and circumstance. Which is surprising given that the book has some considerable champions.

I first heard about Now You’re Logging around 2001 thanks to Seth and The Beguiling’s Peter Birkemoe, who talked about it as if it had talisman-like powers: an improbable comic that had the magical ability to renew one’s enthusiasm in the medium. I’m a little embarrassed to say that it took me nearly a decade to get my hands on a roughed-up library copy of the book, but I’m happy to report that it didn’t disappoint me. But perhaps the only thing that is more intriguing than the comic itself is its origin which stretches back nearly seven decades.

Gilbert Joseph Griffiths was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan in 1913, and became a full-blown fan of comic strips at age 10 around the time his family moved to B.C. As a teenager he pursued a career as a newspaper cartoonist, but after being repeatedly rebuffed as being too amateurish he turned his talents to a job illustrating farm equipment for an agricultural catalogue. After the Depression hit he started logging to make money, a skill he had picked up as a 12-year-old when he felled trees around his rural community for spending money.

Gilbert Joseph Griffiths was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan in 1913, and became a full-blown fan of comic strips at age 10 around the time his family moved to B.C. As a teenager he pursued a career as a newspaper cartoonist, but after being repeatedly rebuffed as being too amateurish he turned his talents to a job illustrating farm equipment for an agricultural catalogue. After the Depression hit he started logging to make money, a skill he had picked up as a 12-year-old when he felled trees around his rural community for spending money.

Then, with the onset of the Second World War Griffiths was given an unexpected second shot at a comics career. Left jobless after the closure of a lumber mill, Griffiths was flipping through the job ads and spotted one from a B.C. company that was seeking original comics. His semi-autobiographical pitch about a crew of 1930s loggers caught the eye of Maple Leaf Publishing (one of four outfits that comprised the “Canadian Whites” era of comics) and Griffiths was soon producing a series of short, eight-page “Now You’re Logging” stories for the company’s Rocket anthology. He produced several of these (along with a cowboy serial) over the next few months when the B.C. government suddenly asked him to return to logging. According to Griffiths, the province believed the overseas war effort would be better served by him producing lumber rather than comics for entertainment–starved Canadian kids. Go figure.

And that should have been that for Griffiths’ brief stint in comics. That is until the 1960s when someone at the Provincial Museum of British Columbia stumbled across his comics and acquired them for their archives as a record of B.C.’s industrial history. This unlikely turn of events prompted an editor at the trade magazine B.C. Lumberman to reprint the “Now You’re Logging” comics as 8-page educational pamphlets and to offer to pay Griffiths to make more.

Griffiths took a five-year sabbatical from logging and fishing to finish off the semi-autobiographical story begun some 25 years earlier. In the 1970s, when the magazine couldn’t afford to pay him anymore, Griffiths shopped a collected edition to Harbour Publishing—a small publisher specializing in books by regional poets and writers—which released a hardcover version in 1978. Apparently, Griffiths’ stated goal with this book was to make the definitive comic about 1930s logging, which he felt had been poorly portrayed by the media over the years. If a nobler goal in comics exists, I’m having trouble thinking of it.

The book tells the story of two rookie loggers: Al Richards (a stand-in for Griffiths) and Red Harris, who sign up to learn the ropes of “truck-logging” along Canada’s west coast during the Depression. Unfolding over a year, the pair faces a series of obstacles and perils which are clearly inspired by classic adventure strips like Captain Easy or Terry and the Pirates. Yet unlike these strips, Griffiths was drawing from a deep well of personal experience which informs his unique graphic novel in a profound way.

The book tells the story of two rookie loggers: Al Richards (a stand-in for Griffiths) and Red Harris, who sign up to learn the ropes of “truck-logging” along Canada’s west coast during the Depression. Unfolding over a year, the pair faces a series of obstacles and perils which are clearly inspired by classic adventure strips like Captain Easy or Terry and the Pirates. Yet unlike these strips, Griffiths was drawing from a deep well of personal experience which informs his unique graphic novel in a profound way.

In the 1930s logging was still very much a manual operation, which means trees were cut down using little more than axes and ropes—the chainsaws and machinery we associate with it were still a decade or so away. As a result, Depression-era logging was widely acknowledged as one of the most dangerous jobs in B.C. and the men who worked in it earned larger-than-life reputations as hard-living guys whose toughness was unchallenged.

Once described as a “husky, clinker-built barrel of muscle and sinew,” Griffiths understands this in a way a career cartoonist could never fathom. His sympathetic depictions of the physical poetry of logging and the resilience of the men who chose to do it is evident on every page of this beautiful, brusque comic.

As you follow the adventures—and budding bromance—of Al and Red, each page and panel is layered with minutely observed period details, whether it’s the weird handle-less coffee mugs or the leather logging gloves, which were specially designed for climbing trees. And no machine here goes unexplained: Griffiths exacting description of a “steam donkey,” a mobile engine used to haul timber onto trucks, is particularly memorable.

Although this near-compulsion for minute details trips up the narrative flow sometimes, it’s easily forgivable when you consider his action sequences. One such set piece involving Al and his crew transporting a steam donkey across a raging river is a genuine thrill to read—and is stacked with enough tiny details to make Dan Zettwoch jealous.

Although this near-compulsion for minute details trips up the narrative flow sometimes, it’s easily forgivable when you consider his action sequences. One such set piece involving Al and his crew transporting a steam donkey across a raging river is a genuine thrill to read—and is stacked with enough tiny details to make Dan Zettwoch jealous.

Then there’s the writing, which will read like music to jaded ears. Griffiths deploys the English language like a backwoods Raymond Chandler: lunch boxes are “nose bags,” shovels are “muck sticks,” and snuff is everything from “snooze” and “Swedish conditioning powder” to “Scandihoovian dynamite”. The jobs in the bush include “choker men”, “whistle punks” and “donkey punchers” while the dialogue is spiked with random poetry such as “It was colder outside than a timber tycoon’s heart.” (A phrase that I hereby pledge to use this coming winter.) A detail-man to the end, Griffiths meticulously catalogues this lingo in tidy, cramped glossaries at the bottom of every page.

Then there’s the writing, which will read like music to jaded ears. Griffiths deploys the English language like a backwoods Raymond Chandler: lunch boxes are “nose bags,” shovels are “muck sticks,” and snuff is everything from “snooze” and “Swedish conditioning powder” to “Scandihoovian dynamite”. The jobs in the bush include “choker men”, “whistle punks” and “donkey punchers” while the dialogue is spiked with random poetry such as “It was colder outside than a timber tycoon’s heart.” (A phrase that I hereby pledge to use this coming winter.) A detail-man to the end, Griffiths meticulously catalogues this lingo in tidy, cramped glossaries at the bottom of every page.

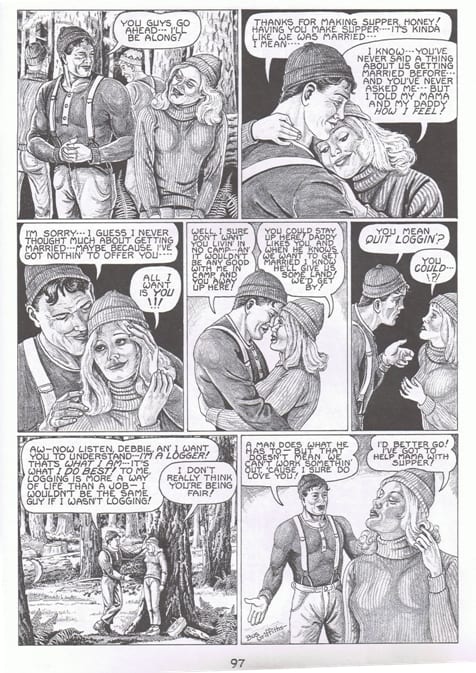

Of course, like any great oddball comic it is not without its hiccups. Griffiths’ female characters (of which there are only two) are humorously one-dimensional. In fact, the entire story threatens to leap of the tracks when he introduces Debbie, Al’s love interest (and a stand-in for Griffiths own wife) who is as interesting as a muck stick. His depiction of Debbie’s emotional range is pained, with her dual expressions of affection and anger distinctly lackluster (but in a compelling way, like Steve Ditko trying to draw a sexy girl). Luckily, these romantic interludes never last more than a page or two before you’re thrust back into the brawny action-packed world in which Griffiths is more comfortable.

Of course, like any great oddball comic it is not without its hiccups. Griffiths’ female characters (of which there are only two) are humorously one-dimensional. In fact, the entire story threatens to leap of the tracks when he introduces Debbie, Al’s love interest (and a stand-in for Griffiths own wife) who is as interesting as a muck stick. His depiction of Debbie’s emotional range is pained, with her dual expressions of affection and anger distinctly lackluster (but in a compelling way, like Steve Ditko trying to draw a sexy girl). Luckily, these romantic interludes never last more than a page or two before you’re thrust back into the brawny action-packed world in which Griffiths is more comfortable.

In the end Al and Red overcome the obstacles in their path, learn the essentials of logging without getting killed, and (spoiler alert!) Al gets his girl. But all of this is beside the point.

In the end Al and Red overcome the obstacles in their path, learn the essentials of logging without getting killed, and (spoiler alert!) Al gets his girl. But all of this is beside the point.

As a comic, Now You’re Logging is quirky and charming as hell. It’s also as pure a vision of working life as comics has ever seen, capturing a little-seen moment in history with such heart and veracity that you can almost smell the sawdust. I’d be hard-pressed to recommend anything else that’d be more deserving of your next infatuation.