Ryan Standfest has just edited a very interesting anthology called BLACK EYE 1: Graphic Transmissions to Cause Ocular Hypertension (Rotland Press), devoted to comics done in the tradition of black humor. To my way of thinking S. Clay Wilson is a pivotal figure in this tradition, although like most of the underground cartoonists Wilson is woefully underappreciated or misunderstood these days. In the hopes of encouraging a new generation to take a  fresh look at Wilson’s work, I wrote a long essay for BLACK EYE trying to explain his centrality in the tradition of outre comics. Below are some excerpts from that essay, which give the gist of the argument:

fresh look at Wilson’s work, I wrote a long essay for BLACK EYE trying to explain his centrality in the tradition of outre comics. Below are some excerpts from that essay, which give the gist of the argument:

Crumb’s Crumb. In innumerable interviews and autobiographical essays many underground and alternative cartoonists talk about the Crumb epiphany. The first time they see Crumb’s work, it hits them like a hammer over the head. “You can draw anything you want,” they think. Crumb’s audacity liberates them to be equally daring and expressive. Monte Beauchamp’s 1998 oral history The Life and Times of R. Crumb contains many accounts of Crumb’s inspirational power. One way of describing S. Clay Wilson is to say that he is “Crumb’s Crumb”: seeing Wilson’s art awakened Crumb’s artistic id. “Wilson had all these drawings full of cocks and cunts and chopping and slicing and stuff,” Crumb told an interviewer in 1970. “He was into drawing anything he felt like and pushing all those things as far as he could.” Prior to seeing Wilson’s work, Crumb’s comics were heading towards greater sexual explicitness but these early strips also tended to be giddy, light-hearted, and even Disney-esque in their winsome cuteness. Crumb hadn’t yet shaken off his training as a greeting card artist. As Crumb admitted in that same interview: “I had always had this kind of built-in censor in my head because I was always trying to do something that had popular appeal, you know? And this censorship was so deeply ingrained in me that I never even thought about it. It was just there.” Wilson changed all that.

A Central Artist. If we acknowledge that Wilson was the artist who unchained Crumb’s unconscious, who gave the final push for Crumb to shove aside his internal censor and be utterly honest, who gave permission for Crumb to become Crumb, then it’s clear that Wilson was the central artist of the underground generation. Of course, there had been transgressive artists of all sorts before Wilson as well as a tradition of black humor in comics (witness Tijuana bibles or EC Comics or Gahan Wilson). But still, Wilson created something radically new. There was something furtive, ashamed, under-the-counter about earlier transgressive artists, the most shocking of whom often did their work covertly for a small audience; what set  Wilson apart was that there is never a hint that he’s embarrassed about what he’s doing; his strips weren’t printed for a coterie, they appeared in Zap Comix which had a print run in the hundreds of thousands. Wilson is not a dirty old man who occasionally flashes his cock out and then quickly hides it with a trench coat: he’s more like an unabashed exhibitionist who is not afraid to walk nude along a busy city street. Wilson’s gleeful depravity, his jaunty nihilism, his open-faced perversity were liberating. He opened up the floodgates and pouring out came Rory Hayes, Ivan Brunetti, Johnny Ryan, and countless others. I’d hazard a guess that most of the artists in BLACK EYE are, in one way or another, Wilson’s descendants.

Wilson apart was that there is never a hint that he’s embarrassed about what he’s doing; his strips weren’t printed for a coterie, they appeared in Zap Comix which had a print run in the hundreds of thousands. Wilson is not a dirty old man who occasionally flashes his cock out and then quickly hides it with a trench coat: he’s more like an unabashed exhibitionist who is not afraid to walk nude along a busy city street. Wilson’s gleeful depravity, his jaunty nihilism, his open-faced perversity were liberating. He opened up the floodgates and pouring out came Rory Hayes, Ivan Brunetti, Johnny Ryan, and countless others. I’d hazard a guess that most of the artists in BLACK EYE are, in one way or another, Wilson’s descendants.

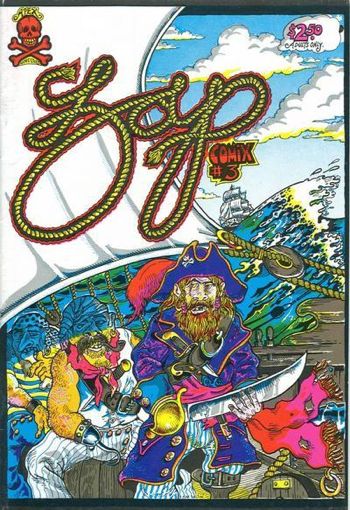

A Visual Stonewall. On June 28, 1969 the New York Police Department launched an early morning raid of the Stonewall Inn. They met with unexpected resistance as the patrons of the bars – gay men, bull dyke lesbians, transvestites – started fighting back. The ensuing riot was the spark for the modern gay rights movement. The Stonewall riot occurred a year after the publication of Wilson’s “Captain Pissgums and His Pervert Pirates” which showed a lusty battle between gay and lesbian (or “dyke”) pirates which ends in a giant orgy. Is it venturing too far to see an affinity between Wilson’s comic and what happened at Stonewall? Wilson art isn’t, God forbid, advocating on behalf of gay rights or any other sort of politics, conservative or progressive. But still, the very act of representing queer sexuality in such a blunt, ferocious way – without the smirk of camp or the winking coyness of earlier gay art – speaks to Wilson’s contribution to the new spirit of freedom. Aren’t his comics a kind of visual Stonewall? The message of the Stonewall riot was: “We won’t be pushed around anymore, we won’t hide our desires in the shadows anymore.” The message of Wilson’s work is “Anything my mind can imagine, my pen will draw. I will not hide in the shadows.”

Note: for information on the S. Clay Wilson Special Needs Trust, go here.