Just think of it: a comic-con without movie or television stars. No Hollywood. No gaming. No cosplay. And no superheroes to speak of. What kind of a comic-con is that? Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC) is another of a rare breed— a comics festival for people who love comics and the art of cartooning. And it’s all free. No charge. Just come to Columbus, Ohio.

For four days in Columbus, October 13-16, the CXC organizers’ “mission was to make Columbus the cartooning capital of the world,” said Tom Spurgeon, Festival Director, in an interview with Tim Hodler on this site in early October.

Spurgeon was picked for the job after the first “soft launch” of CXC last year. CXC needed a manager. As editor of this magazine from 1994 to 1999, he knew a lot of people in the field, and his connections were valuable. One of the CXC founders, Jeff Smith, was among the first cartoonists Spurgeon interviewed after arriving at TCJ and Smith reached out to Spurgeon, who moved to Columbus from his hideout in New Mexico where he produced The Comics Reporter.

“Festival director,” Spurgeon told Hodler, “means I’m primarily responsible for the logistics of it, the making it happen of it. That’s both in just making sure stuff gets set up but also that we’re executing according to our goals and ideals.”

Why Columbus?

Because the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum on the campus of the Ohio State University is in Columbus. The Billy Ireland houses the world’s largest collection of original cartoon art and related books, magazines, and newspaper clippings, and the Billy Ireland actively promotes interest and scholarship in the arts of cartooning, staging numerous exhibitions and seminars throughout the year.

Other special comics events through the year include the Small Press and Alternative Comics Expo (SPACE) and the Independent Comics Fair.

Falling in line, the Columbus College of Art and Design recently announced the addition to its curriculum of a new Comics & Narrative Practice major. Columbus Alive, a free weekly in town, devoted its October 13 issue to CXC; the coverage began with an article about cartooning in the city, “25 Essential Columbus Comics,” graphic novels and comic books produced by local cartoonists.

And Ohio has an ample cartooning history. Scores of cartoonists were born in Ohio or spent significant time there. The reputed “father of American newspaper comics,” the Yellow Kid’s Richard Outcault, was born in Ohio. Ditto Billy Ireland, Milton Caniff, and James Thurber; others lived and worked in the state— John “Derf” Backderf, Brian Michael Bendis, Billy DeBeck, Roy Doty, Al Frueh, Cathy Guisewite, Charles Landon, and dozens more, from Gene Ahern to Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel to Bela Zaboly.

The first two days of the four-day CXC took place at the Billy Ireland, with programming and special exhibits; the succeeding two days transpired downtown at the city’s Metropolitan Library, where the CXC Expo opened. Spinning out from those two sites, the CXC took over the city with special exhibits at various venues.

CXC replaces the triennial festival of cartoon art that was sponsored by the Billy Ireland for many years. The idea of CXC founders Jeff Smith (Bone) and Lucy S. Caswell (curator emeritus of the Billy Ireland) was to make Columbus the Angouleme of America. Like the International Comics Festival in France in January of every year since 1974, CXC would take over the host city.

For Smith, CXC is a dream come true. “I had this idea,” he said, “What if we could bring these artists together on one weekend in Columbus? This isn’t the kind of event where people come dressed up as Captain America (although they’re free to do that if they want to). These artists are people that are working from their own voice.” As Smith did in creating Bone (which, this year, celebrates its 25th anniversary).

This year, CXC took over Columbus from Wednesday evening, October 12, with a preamble event, through the following Sunday.

There’s no registration. No list of attendees. (And people, including Columbus residents, come and go all weekend.) And no head count. Attendance at last year’s “soft launch” was estimated at 600-1,200.

With no formal registration required, determining how many people enjoyed this year’s Festival requires looking at several aspects of the event. The scholarly presentations at the Billy Ireland were not counted, Spurgeon told me (I counted about 130 people at one of the second day’s presentations), but Wednesday evening’s screening of Mark Osborne’s “The Little Prince” was estimated at 200 based upon the available seating; similarly, at Thursday evening’s rare public appearance of Garry Trudeau, 750 people filled seats at the Mershon Auditorium.

At the Library downtown, Spurgeon said, “we were 2,200 over average attendance on Saturday, and 1,600 on Sunday.” There’s no advance printed promotion. To get yourself oriented, you must start at the web site. The closer CXC came, the more programming popped up on the site. So before I booked a hotel room and bought my plane ticket, I knew the first official event was Wednesday evening, and that the programming began Thursday morning at the Billy Ireland with coffee and pastries at 8 a.m. I showed up there at 8:30 a.m. and picked up the printed program and a cup of coffee. I was handed a blank name badge (no preprinted badge with your name; no one knew I was coming—no registration, remember?) and wrote my name on it.

The program booklet told me about the exhibits all around town:

At the Columbus College of Arts and Design, selected original art provided by Nate Powell from March: Book Three, the final autobiographical volume of Congressman John Lewis’ engagement in the Civil Rights Movement. Powell signed copies of the book on Saturday. At the Columbus Museum of Art, selected original art by artist-in-residence at the Thurber House (where James Thurber grew up), Ronald Wimberly, who appeared on the program on Sunday in conversation with OSU’s Jared Gardner. At the Wild Goose Creative, the Sunday Comix Group presented Comics vs Art: Fine Art Isn’t Just for Adults Anymore, “a show that playfully reimagines fine art as comics panels.” OSU’s Barnett Collaboratory, cartoonist Keith Knight and collaborator Matthew Schwarzman appeared in “an evening of ideas, games and live art called Sex, Lies and Social Change: The Roots of Community-Based Arts.” At the Boat House, the Columbus Metropolitan Club offered a special CXC program featuring animator Mark Osborne (“Kung Fu Panda,” “The Little Prince”), editorial cartoonist Nate Beeler (Columbus Dispatch), and graphic novelist Ronald Wimberly (Prince of Cats).

On Friday, the Sol-Con Expo and Workshops was scheduled to take place at OSU’s Hale Hall. This event was founded in California by John Jennings and Ricardo Padilla to foster awareness (among the public and among the affected minorities) of Latino and African American comics and their creators by showcasing their work. Said Jennings, interviewed in Columbus Alive: “Basically, it’s a way to combat symbolic annihilation, which is erasure through omission. It’s a way to empower people who haven’t been able to see themselves in mainstream comics and media.”

And at the Billy Ireland, two special displays (in addition to the permanent exhibit): Good Grief: Children and Comics, which examines “the history, role and tensions of child characters in comic strips and comic books”; and Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, which combines original art from the Nemo tribute book of the same name with resources from the Billy Ireland’s extensive collection of Winsor McCay material. And on Friday, an Open House offered special tours of the facility (leaving every hour) and a display of some of its treasures in the Reading Room.

The program booklet also listed (and annotated) the CXC special guests: cartooning legends like Garry Trudeau, Sergio Aragones, Ben Katchor, Ed Koren, Carol Tyler, Stan Sakai, John Canemaker, Seth, Charles Burns; modern stars Raina Telgemeier, Brandon Graham, Julia Gfrorer, Jay Hosler, Mark Osborne, Sacha Mardou, Skottie Young, Ronald Wimberly; skilled practitioners of their craft like editoonists Ann Telnaes and Nate Beeler, satirists Keith Knight, Lalo Alcaraz. All of these caroonitsts made presentations throughout the weekend. What follows are a few highlights, day by day.

THURSDAY

The presentations began Thursday morning at the Billy Ireland with the first of the two day-long scholarly symposium featuring about three dozen presentations, all gathered under the umbrella heading “Canon Fodder!”

The cultural status of comics has improved over the last 30 years, particularly since the success of the so-called “graphic novel,” which term, by avoiding the word “comics,” helped make comics socially respectable. And social status in combination with a tsunami of new and much better work fostered study in academe—hence, the need for determining a “canon,” a list of essential comics works. "What are the great comics?” The printed program asked. “What are the comics everyone should read? An all-star line-up of scholars and thinkers sit down under the CXC banner for a two-day summit on the making of canon. Who gets to decide the comics canon? Who gets left out? What are the implications of canon building for the academic, for artists, for the art form?”

I sat with 60-130 others in the audience (the count varied from one time period to another and from Thursday to Friday) and dutifully took notes, often about presentations that I could barely hear. I’m about half-deaf (don’t ask which half), and some speakers spoke more softly than others. Although I had a sound magnifying gizmo with me, I probably missed as much as I heard. So what follows is more a summary of major points (and not all of them) than a detailed examination of any of them.

The headlong growth of comics studies in colleges and universities now embraces histories of the medium, of genre (heroes, funny animals), of publishers, and of cartoonists/artists and writers. And as the social media took over human interaction, social media and the comics became a legitimate subject for study.

Ally Shwed, cartoonist/writer/visiting prof of sequential art at Tecnologico de Monterrey in Queretaro, Mexico, discussed the growth and influence of social media on the determination of canon under the heading: “To Pander or to Play the Game: Fan Interaction and Comics Canon in the Digital Age,” her argument taking the following route:

Industries no longer have control over how their brand is disseminated: that’s been taken over by the social media. Letter columns in comics were an early form of interaction between publishers and consumers, and publishers controlled what was made public. With social media, that control is no longer possible. The Internet, fostering a kind of anonymity, de-individualizes by grouping like-minded consumers. Individuality is subsumed in the resulting sense of power in groups, and the growth of groupings weakens any sense of personal responsibility for what one says even as it enhances the influence of individuals through the group.

Group responses can overwhelm the hierarchies of power. Social media protested a recent cover of a version of The Killing Joke and got it withdrawn. Ditto the connection between Captain America and Hydra because the connection was not consistent with the Joe Simon/Jack Kirby character as initially conceived. The Internet eliminates barriers between the readers and producers of comics. Smart publishers acknowledge the power of social media. And so fans help create canon to a greater extent today than ever before.

This may seem a laborious way to arrive at the conclusion that social media has the power to determine canon, but tracing the route of the reasoning is one of the attributes of the academic enterprise in comics studies.

In other presentations, the history of comics was seen as a history of influences. Australia’s cartooning historian Ian Gordon argued for more comparative histories. He maintained, for instance, that Jimmy Bancks was undoubtedly influenced by Percy Crosby’s Skippy when, in 1921, he concocted and conducted Us Fellers, a strip that eventually morphed into Ginger Meggs, becoming virtually a national institution in Australia. I’m not quite convinced: in the early days, Ginger Meggs was about a gang of kids; the eponymous Skippy was usually presented as a loner, particularly at first.

Besides, the timing is a little off: Skippy, which began in the old Life humor magazine in March 1923, didn’t get into newspapers until syndicated in 1925, and then by a bush league syndicate; the strip didn’t get major distribution until Hearst took it over as a Sunday in 1926 (daily, 1929). So it’s unlikely that Bancks saw the feature until at least 1925, four years after he started Us Fellers, or maybe as late as 1926. But there could still be some kind of influence. Dunno when Us Fellers began focusing on one of the fellers, Ginger Meggs, who became the title character. But it’s possible that Bancks began concentrating on one mischievous character after seeing Skippy —somewhere, in Life or in newspapers. (See? That’s the sort of hair-splitting that scholars, even mere chroniclers like me, get involved in.)

Autobiographical comics were mentioned as candidates for the canon—especially those starring Scribbly, who, in comic books, was the cartoonist alter ego of his creator, Sheldon Mayer. Thursday evening was occupied by John Canemaker, the award-winning animator and historian, who, with illuminating commentary, presented several of Winsor McCay’s celebrated animated films (with Nemo and Flip, about how a mosquito operates, and the famed “Gertie the Dinosaur”).

FRIDAY

The scholarly presentations continued most of the day.

John Jennings, a professor of media and cultural studies at the University of California at Riverside and an artist with several comics to his credit (a couple pages of a current comic book/graphic novel project, Blue Hand Mojo, appear near here), talked about “Marvel Comics Original Cloak and Dagger Series as Anti-miscegenation Narrative.” He deviated from the usual academic practice of “reading a paper.” He occasionally quoted from his paper on the comic book heroes (Cloak and Dagger representing white and black cultures respectively), but he mostly talked extemporaneously, often interjecting self-deprecating asides or humorous observations (“What is the shadow in darkness?”), sometimes recommending further reading or research on the topic, while he showed pictures illustrating his premise.

Daniel Yezbick, professor of English and media studies at Wildwood College in St. Louis, Missouri and author of Perfect Nonsense, an appreciative biography of George Carlson from Fantagraphics, read from his paper— but forcefully, with emphasis and wild gesticulation. The topic was “The Action Figure as Embodiment and Extension of Comic-Book Continuities.” He presented images of action figures that “extended the lives of comic book superheroes” and called for further study.

Afterwards, I asked him if he was serious. “Weren’t you being satirical about academic comics studies?” I wanted to know. He laughed. But “expanding the canon” was, after all, one of the subtopics of the seminars. Someone mentioned the German doll, Lilli, who morphed into a panel cartoon character and then into Barbie, “the iconic toy of the 20th century.” Another presenter talked about the a-sexuality of Jughead Jones in Archie Comics—“a form of queer relation.”

Here’s a selection of some of the topics of the two-day seminar:

Cultivating Transnationality in the Comics Canon: on Spain and Latin America

How Lust Was Lost: Genre, Identity and the Neglect of a Pioneering Comics Publication

A Fabric of Illusion: C.C. Beck’s Critical Circle and His Theory of Comic Art

Seeing Deafness: Representing an Invisible Disability Through the Visual Rhetoric of Superhero Comics (“We tend to equate fluency with literacy, an outdated model”)

Decentering and Recentering in the Field of Comics

Ach! Female-Created Comics Strips and the Scholarly Canon

The more seriously such obtuse subjects are considered, the more self-satirical the presentations seem to become. Maybe it’s just me: after a day-and-a-half of these effusions, I was beginning to see satire wherever I looked—Yezbick’s paper on action figures, for example.

Esoterica aside, I enjoyed as much of the presentations as I could hear. And many were provocative. “The error of equating fluency with literacy,” someone said, is a tantalizing notion, worth pondering further.

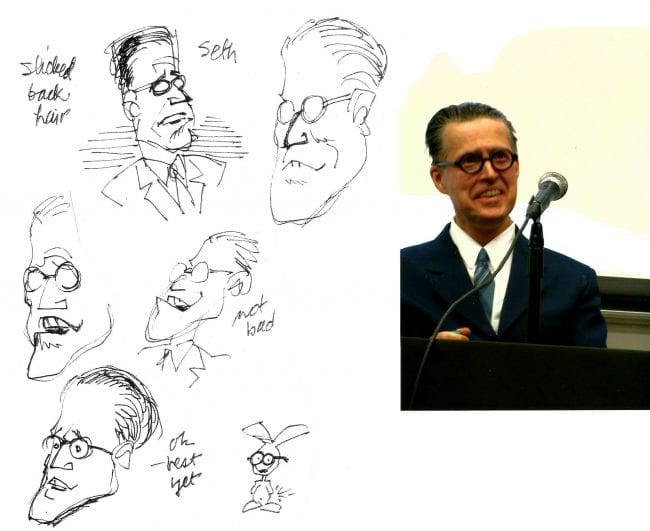

Later in the afternoon, Canadian cartoonist Seth took the stage in conversation with Craig Fischer. Seth was, judging from the audience’s reaction, an amusing as well as informative speaker. Among his thoughts: anyone aspiring to doing comics has an obligation to learn the history of the medium. Charles Schulz thought the same. But I couldn’t hear much of what Seth was saying, so I amused myself by trying to caricature him.

The day’s agenda concluded with a panel discussion on “The State of the Industry.” The panelists included Brendan Burford, comics editor at King Features syndicate, Shena Wolf (GoComics.com), Chip Mosher (comiXology), and Keith Knight (self-published). Burford, who’s worked at King for 17 years, 10 of them as comics editor, said his department consists of 53 employees. In today’s newspaper market, the question always is: what’s worth taking a risk on. But as newspapers struggle to survive, said he, “We have to change the way syndicates operate and what they do.” But he offered no specific suggestions—even though the topic must be under more-or-less continuous discussion at his office.

“Most of the great cartoonists,” Burford said, “can’t stop themselves.” Hence, his advice to aspiring cartoonists looking to get syndicated: “If you can’t not do it, then you can think about syndication.” Wolf, at one point, chimed in: “Sometimes we give up on something or don’t accept it just because it isn’t like what we’ve done before.” Knight added his usual unconventional perspective. He goes to lots of shows that aren’t comics shows. That enables him to cultivate readers that aren’t in the usual crowd. When he wasn’t speaking, he was listening while he also drew a daily installment of his comic strip, The Knight Life. At the beginning of the session, he asked if anyone in the audience had an H2 pencil; someone did, and loaned it to him for the duration of the panel. A question that lurked through the presentation: Are comic books and graphic novels taking the position in the cartooning industry that once syndicates held?

The afternoon ended with a reception in the Billy Ireland. Mad’s Sergio Aragones and Carol Tyler, underground comix legend, were presented with Masters of Cartooning Arts awards.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the campus, the all-day Sol-Con: The Black and Brown Expo and Workshop was transpiring. The event featured a “slew of local and national Latino and African American creators,” showing their wares in a variety of genres, formats and styles and participating in workshops and academic panels.

“They are creating these really vital, kinetic African American or Latino superheroes, said Frederick Luis Aldama, who teaches film, comics and Latino pop culture courses at OSU. “But then there are others that are working to use the visual and verbal craft of comics to tell everyday heroic stories.” The stories, he continued in Columbus Alive, “are as exploratory as the mind is infinite, but grounded in concerns that we experience as Latinos and African Americans in this country, things like discrimination, lack of access to education, racism, homophobia and sexism.” Aldama has authored two scholarly books: Your Brain on Latino Comics: From Gus Arriola to Los Bros Hernandez (332 6x9-inch pages, b/w; 2009 U. of Texas Press, paperback, $29.95) and Latinix Comic Book Storytelling: An Odyssey by Interview (270 6.5x10-inch pages, occasional color; 2016 Hyperbole Books/San Diego State University Press paperback, $24.95).

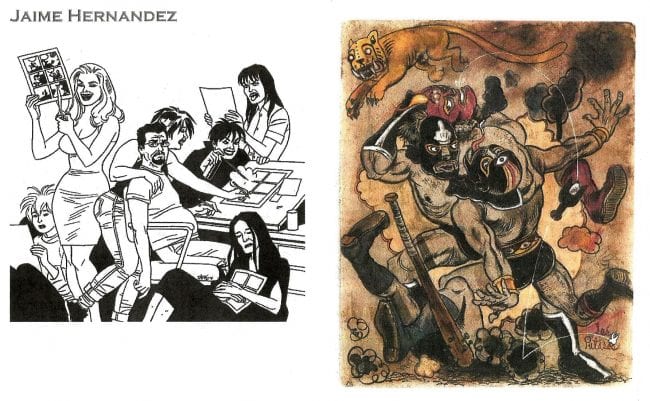

In his first book, Aldama begins by tracing the history of comics by and/or about Latinos (including the occasional appearance in mainstream funny books), pausing to describe some of the heroes, some of their adventures, and some of the cartoonists. The last two-thirds of the book consists of interviews with Latino/Latina cartoonists and/or writers, 21 of them. The second book is entirely interviews, 29 of them, including only 4 that appeared in the previous volume. Among those interviewed are Hector Cantu and Carlos Castellanos (creators of the contemporary syndicated strip Baldo), Gus Arriola (creator of Gordo, a syndicated strip that ran for over 40 years, starting in 1941, and the subject of a book of mine, Accidental Ambassador Gordo; this interview, Aladama told me, he believes was the last Arriola gave before he died), Roberta Gregory, Los Bros Hernandez (Gilbert and Jaime), Lalo Alcaraz (creator of the syndicated strip La Cucaracha) —alas, the only names I know.

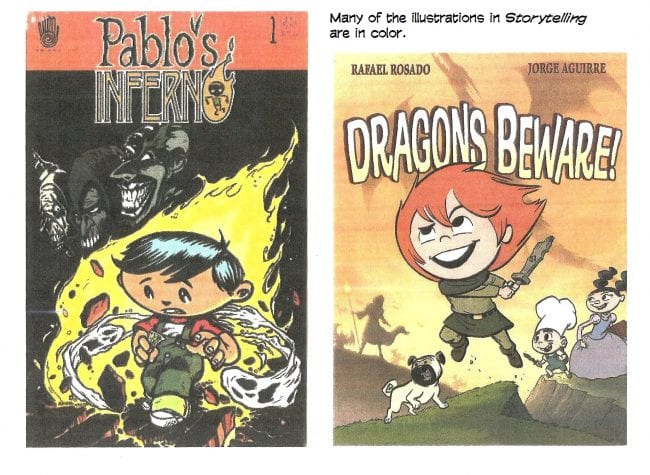

Both books are modestly illustrated: not every work is depicted in Your Brain, but many are, albeit in black-and-white. The Storytelling volume offers at least one illustration for each of the cartoonists interviewed—and most of them are in color.

This brace of books are the best way to equip your library for dealing with an emerging cultural event—cartoons and comics by Latinos. If you have something you need to look up, you can probably find it in one of these two tomes.

This brace of books are the best way to equip your library for dealing with an emerging cultural event—cartoons and comics by Latinos. If you have something you need to look up, you can probably find it in one of these two tomes.

Friday afternoon, the spotlight fell on Garry Trudeau, who was “in conversation” with author Glen David Gold on the stage at Wexner Center’s Mershon Auditorium at OSU. Trudeau seldom makes public appearances, so his gig at CXC was a rare event and attracted a big crowd. I don’t think there were many empty seats in the auditorium: all of the CXC events were open to the public, and this event, like several others over the weekend, had been written up in advance in the local newspaper, the 145-year-old Columbus Dispatch, and the publicity pulled in ordinary civilians—comic strip readers and aficionados, not just cartoonists and comics scholars.

In an article in Columbus Alive, Trudeau the political satirist was asked about Trump. Did he buy into the notion that Trump really doesn’t want to win, that he launched his campaign as a publicity stunt? Trudeau’s response was typically acerbic and insightful: “No,” he said. “That’s what normal people call an ‘ulterior motive,’ which implies delayed gratification, of which Trump is incapable. When he says he wants to be in the White House, you have to believe it because it’s very short neural pathway between his id and his mouth.” Is Trump’s candidacy a “mere sign of the times or is it symptomatic of larger issues we can’t hope will be swept away by his potential defeat?” “A one-off,” said Trudeau. “But that doesn’t mean the GOP doesn’t have a Herculean task of reconstruction ahead of it. All the china’s been broken, and that’s not even good for Democrats. We need at least two functioning, philosophically robust parties to make our system of government work.”

Gold got Trudeau talking by showing some of the controversial Doonesbury strips and asking the cartoonist to comment on them. Trudeau’s been quizzed by newspaper reporters about many of the more sensational strips, so when Gold put one up on the screen—Joanie Caucus famously waking up in bed with Rick Redfern, for example (a strip that more than 30 client newspapers chose not to publish)—Trudeau had talked about it before. And he did again here.

Among the strip images Gold displayed was the one in which DB was shown just after being wounded in Vietnam. He lost a leg in the process, but, said Trudeau, the thing that caused the most comment from readers was that DB’s helmet was removed while he was unconscious. No one had ever seen him without his helmet. He’d started Doonesbury life in a football helmet and was never seen without it—and when he went to Vietnam, he was never seen without a military issue helmet that concealed as much of his head as the football helmet had. Readers were stunned to see him bareheaded. That he was also missing a leg was apparently of less concern to readers. And DB’s surprising appearance without head gear symbolized and emphasized the drastic change that the character was going to undergo. At the end of the conversation, CXC president Jeff Smith came back on stage and presented Trudeau with the CXC award for Transformative Impact on the Profession.

Various saloons around town had been designated as CXC watering holes where the festivities would be hosted by some of the visiting dignitaries. Enjoyable as they undoubtedly were, I, aged and half-deaf, went to my hotel and bed.

SATURDAY

The CXC Marketplace and Expo opened at 11 a.m., and the Festival moved away from the Billy Ireland on campus to downtown Columbus. At the Columbus Metropolitan Library, almost 100 display tables were staffed by creators selling their own books (including 15 from Sol-Con) and magazines and by publishers doing the same with theirs. I was surprised to see so much high quality work being published by independent creators. Fantagraphics had a display, as did OSU Press and IDW (and others, no doubt; I must’ve missed a few).

About 20 panels and individual presentations ran parallel all day long in meeting rooms throughout the Library. Unlike the scholarly programs of the previous two days, these hour-long sessions featured cartoonists, not academicians. Every cartoonist who was a special CXC guest (see the list at the beginning of this extravaganza) was interviewed or made a presentation. Several also did drawing demos. And Sol-Con joined in the festivities, offering a strand of programming. Charles Burns at another downtown venue discussed his career; Nate Powell talked about the March books he’d drawn. Raina Telgemeier did a solo session; ditto many others. I went to a session featuring The New Yorker’s Ed Koren being interviewed by Tom Spurgeon. I placed my mini-microphone on the table, but Koren kept moving his chair away from the table. I heard very little.

At a session on political cartooning, the presenters represented a range of minority passions—Ann Telnaes, sexism/feminism; Lalo Alcaraz, Latino; and Keith Knight, African American. Nate Beeler, Columbus Dispatch editoonist, moderated. The panelists were seated at a table, and behind the table, a projection screen had been dropped from the ceiling so the cartoons of the presenters could be displayed as they talked.  After projecting a couple dozen cartoons, the computer-projector failed to work, so the panelists plunged onward without it. Then, several minutes later—suddenly, without explanation—the projection screen was pulled back into its ceiling nest, rising silently like spooky wraith. Telnaes and Knight and Beeler chimed in with a couple jocular comments on the mysterious ways of projection screens and the ominous import of the screen’s disappearance, but Lalo said nothing. Looking a little alarmed, he stood up, staring at the audience, then he turned around, putting his hands on the wall behind the table and spreading his legs in the classic posture of a miscreant apprehended by law enforcement.

After projecting a couple dozen cartoons, the computer-projector failed to work, so the panelists plunged onward without it. Then, several minutes later—suddenly, without explanation—the projection screen was pulled back into its ceiling nest, rising silently like spooky wraith. Telnaes and Knight and Beeler chimed in with a couple jocular comments on the mysterious ways of projection screens and the ominous import of the screen’s disappearance, but Lalo said nothing. Looking a little alarmed, he stood up, staring at the audience, then he turned around, putting his hands on the wall behind the table and spreading his legs in the classic posture of a miscreant apprehended by law enforcement.

There were serious moments thereafter—and a couple more humorous ones; but nothing will ever compare to Lalo’s spontaneous demonstration of a persecuted Latino.

In a reflective moment later, Telnaes warned about the sexism we could expect to see emerging more obviously once Hilary is elected—just as racism bubbled up after the election of Obama.

Later in the afternoon, Knight made a solo presentation entitled “They Shoot Black People, Don’t They.” He’s been doing this presentation around the country for months, often at gatherings having nothing to do with cartooning. Raised in Massachusetts, Knight didn’t have a black teacher until his junior year in college when he enrolled in an American literature course. “My teacher, who was black, assigned James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Maya Angelou—all black writers—for us to read,” Knight explained in a newspaper interview published over the weekend (and he said pretty much the same during his presentation). “Someone brought up the idea, ‘Why are you giving us all black writers?’ and the teacher said, ‘I’m giving you all American writers.’“When he said that, that’s what made me want to change my work: knowing he was working within the system but he was an activist.”

Knight has been an activist for more that 20 years, embracing cartooning as a means of confronting big ideas of race, identity, cultural appropriation, police misconduct and more in his three cartooning ventures: K Chronicles, a weekly autobiographical comment on the passing scene; The Knight Life, another autobiographical enterprise, this one a syndicated daily comic strip; and (th)ink, an occasional overt political panel. He started reporting his personal experiences in his cartoons because he didn’t see anyone he identified with represented in the medium. “When I look at editorial cartoons,” he said, “I never see the average joe as a person of color. The best cartoons,” he continued, “can take complex issues and sort of simplify them. Not to present them and to say, ‘This is a simple issue,’ but to get people to understand an argument in a simple way.”

He showed some of his cartoons during his presentation, but mostly, he talked. He cited statistics. He related several personal experiences that exemplified the ludicrous absurdity of racism in America. Once, he said, he had been putting up posters around his neighborhood when he was accosted by police. Looking for someone who had burgled a house, they were acting upon a description—“tall and black.” That was the description. That was all. Knight was tall and black, but, he pointed out, he was sporting a dreadlocks. He related other instances in which white people were “privileged” in a way that a black person, in the same circumstance, was not. A white man can yell and scream at police; a black man can’t.

SUNDAY

CXC stayed in the same places, and the day’s events were pretty much the same as Saturday’s—the expo, parallel programing, and spotlights on special guests. Seth joined Ben Katchor “in conversation” at the Museum of Art, and Raina Telgemeier was “in conversation” with Jeff Smith at the Library.

And the Wild Goose Creative offered an exhibition of comics art inspired by Western paintings: “Imagine an exhibit hall lined with paintings by Western artists from 1400s through modern times. Imagine these works mysteriously transformed into words of comic art.”

I left about noon on Sunday, just as the day’s events were getting going at the Library, so I can’t report much of what happened. But I’ll certainly return to Columbus for next year’s CXC. It’s a better event for comics lovers than any of the comic-cons I’ve attended.

We leave with Spurgeon’s comparing CXC to other comic-cons while talking with Hodler: “Most conventions are like tent revivals that pull up and leave when the weekend is over; we’re a series of churches—in the case of the Billy Ireland, a cathedral—and we’re still here that next Monday.”