So what’s up with this Michael DeForge character, anyway? What’s his dilly? Does he fight the X-Men or what?

Ah, but I kid, I kid. We all know who DeForge is. He’s great. Works a lot. Distinctive yet very mutable style, isn’t afraid to do something completely different. Heaven No Hell is the book today, a new collection of short pieces from DeForge’s longtime publisher, Drawn & Quarterly.

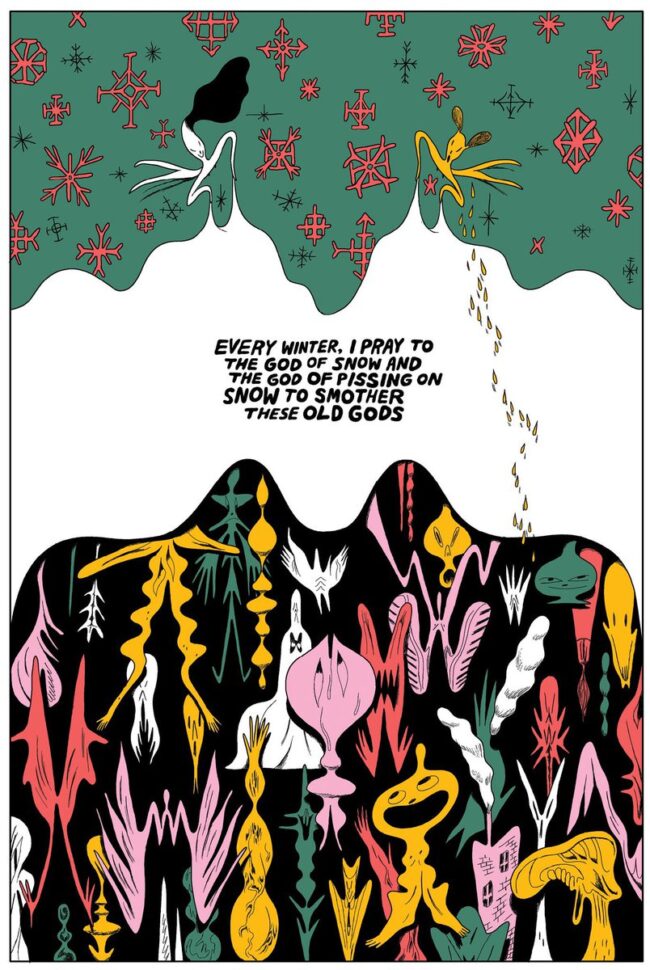

There’s often an element of contingency to DeForge’s line, as if he has begun his composition by dropping a piece of string from a foot above the page and tracing the resultant shape. Figures bend and distend freely. Sometimes the action is difficult to parse, you might have to stop to decipher unexpected lines.

Look at “No Hell,” perhaps my favorite piece here. Only second at bat and short. It’s about the afterlife, funny and terrifying in equal measure. The illustrations aren’t quite figurative and aren’t quite abstract. Angels and demons appear wisps of cloud floating through cosmic teeth. The afterlife described here doesn’t seem particularly pleasant. Decent people get to fuck Nora’s husband in heaven. Ultimately it turns out that the godhead is a giant demon masticating on unexceptional human souls. Exceptional souls get to hang around to judge the living. Because isn’t that what the thing is about, a gnarly hallucinogenic Robert Williams canvas taken apart and reassembled by someone trying to get over the guilt of having slept with Nora’s husband? Makes sense to me.

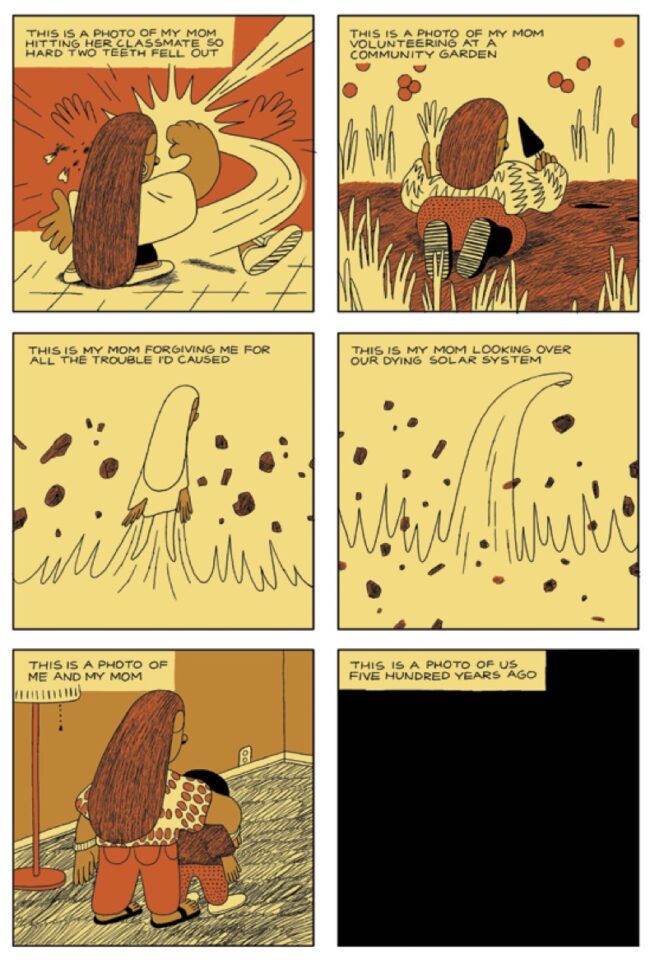

It’s difficult sometimes to get a handle on DeForge. Switching up style with every piece is a great way of showcasing virtuosity - and, you know, mission accomplished on that - but it’s a baller move that also makes it difficult to size up the book as more than the sum of its pieces. That’s a trap for short story collections in any medium. What binds the collection across these many disparate pieces and styles is not DeForge’s style, which remains protean throughout, but his voice. The stories here are mostly fables and anecdotes, dystopic sketches in a number of modes. The only prevailing thread is an elemental misanthropy, generational to judge by the acceptance of the tragicomic deadpan as the universal voice of older millennials.

For a cartoonist DeForge has a very distinctive presence as a prose writer. There are multiple instances of illustrated panels accompanied by text. “Song Selection” is a sequence of images telling the story of a night out for karaoke during a snowstorm that seems more eventful than necessary. It ends with this memorable passage, as clear an evocation of the slow grief of aging as you are likely to find:

We woke up healthy. We woke up in agony. No one overdid it, since none of us overdo it anymore. There were less of us than there were last year. Some day we’ll wonder how we ever managed to pack a room. None of us had hangovers. We’ve cut back on our drinking.

“New Museum,” tucked deep into the back half of the book, is another example of this format. There’s nothing at all sequential here, rather we see a succession of images illustrating the final conflict between figurative and literal thinkers. Apparently there wasn’t just a war but a rout, described as such:

Every realist was, at least, maimed, beheaded, or crushed under boulders. No more hand-wringing; we lopped off their hands. The mealy-mouthed had their tongues forcibly tied. We fed their appendages to dogs, finally making themselves useful for once.

What accompanies this grim recitation? A surreal landscape demarcated by abstract squiggles and strange eruptions of parallel lines. The horizon is broken by splotches of ink resembling the striations of illustrated Kirby chrome. Disembodied eyes overlook a field of queasy pastel pink. Look at it for a minute and you can see something more figurative, if only just - tiny little cartoon men being crushed under giant rocks, Giles Corey style for the real OGs in the house. Who do these sequence remind me of, more than anything? Ralph Steadman, an artist oft disinterested in portraying the natural as anything other than chaotic disruption across fields of empty geometry. He also often exhibits multiple styles within the same drawing.

Namedropping stylistic referents can be lazy shorthand that, in announcing the critic’s ample understanding, further obscures that of the audience. It can feel cheap. I struggled with the impulse while reading Heaven No Hell, because DeForge is so clearly trying to inspire that kind of reaction, by leapfrogging so assuredly across technique and style. It’s a book to scratch the critic’s chin, certainly, but what are you getting out of it, dear reader?

It adds up to more than merely an exercise in spot-the-pastiche, I assert, even if some of the referents are easier to see than others. Two very different names occurred to me multiple times throughout the book, Jerry Moriarty and Larry Marder. You’d struggle to find two more different indie books than Jack Survives and Beanworld, but these are the twin stylistic poles that much of the book seems to swing between - Moriarity’s abstracted naturalism and Marder’s highly metaphysical minimalism. With “One of My Students is a Murderer . . . But Which?” Deforge gives us an entire middle school mystery story in the style of something between Nancy and Skibber Bee-Bye. There’s little here of the hands that created 2014's Ant Colony. “Kid Mafia,” the penultimate piece in the collection, is about a group of kids hanging around the neighborhood and learning about the birds & the bees. It’s the most “normal” story here inasmuch as it’s just a story about normal people shooting the shit and making out, with nary a speculative conceit in sight. The color is garish but it’s all about the body language, real people interacting in a real environment. “Road Trip” precedes it by a few pages, and features rounded stick figures walking through a purgatorial afterlife demarcated by squiggles and smudges while having a metaphysical conversation.

“Role Play” leads the collection, a narrative built around the unvarying width of DeForge’s line. There are no gutters between panels, and the lines between panels are just the same width of the lines that demarcate the panel borders. It seems very much within the realm of what I might expect from a DeForge comic even if, as you may have inferred, DeForge doesn’t necessarily have that consistent a style to begin with. But it’s good. Oddly enough, despite the claustrophobic framing, the story flows quite smoothly. In the absence of gutters the panels move like frames of a movie reel. Quite effective.

There’s nothing here that doesn’t work, even if you might not like each story equally. It seems a cousin to Eleanor Davis’ How to Be Happy, another stylistically polyglot collection by a young artist seething with talent and unafraid to efface their own style in the name of growth. Also one of the strongest books of the last decade. Anyway. I just checked and DeForge isn’t even thirty-five years old, the kind of sadistic factoid that makes you want to just pack it all in and move to the Yucatán.