Genre storytelling has long been a means through which real world issues have been parsed. Our values and fears are reflected and refracted in the stories we consume. As we struggle to move on from the global pandemic -- even as COVID variants continue to ravage some corners of the globe -- the inequalities that the crisis laid bare are proving difficult for the powerful to sweep back under the rug. It’s safe to assume that a crop of pandemic-themed entertainment is not too far off.

Night Hunters and Beef Bros, a pair of recent releases, don’t address the pandemic specifically, but they do explore the social ills that were brought into stark relief by the pandemic in insightful ways. To call these books timely would be appropriate, but also an understatement. For millennials and zoomers, they also feel timeless, since the issues highlighted in these books have cast a shadow over our entire lives. Both of these stories posit how we might move beyond the obstacles inherent to neoliberalism, such as class division and inequality, scarcity of resources, and rampant government privatization and deregulation. These titles also raise questions about what role socially progressive genre comics can play in realizing this vision.

Night Hunters, by artist Alexis Ziritt and writer Dave Baker, is a four-issue limited series published by Floating World Comics, following a successful Kickstarter campaign. It follows adopted brothers Julian and Ezequiel throughout their lives on the mean streets of Gran Caracas, a crime-ridden city sprawl in the Venezuela of 2057 through 2078. Tantamount to life in an open-air prison, life in Gran Caracas is brutal and unforgiving. A fascist, corrupt police force modulates the movement of citizens among the city’s various zones, quarantining the indigent out of the sight of their social betters. It’s a life of abject indignity and constant humiliation. Julian, Ezequiel, and their father, Juan, do their best to get by, scavenging for scraps they can sell and trying to move through the various real and socio-political checkpoints of their small world without raising the ire of the cops or falling prey to their fellow citizens, who are ultimately trying to do the same.

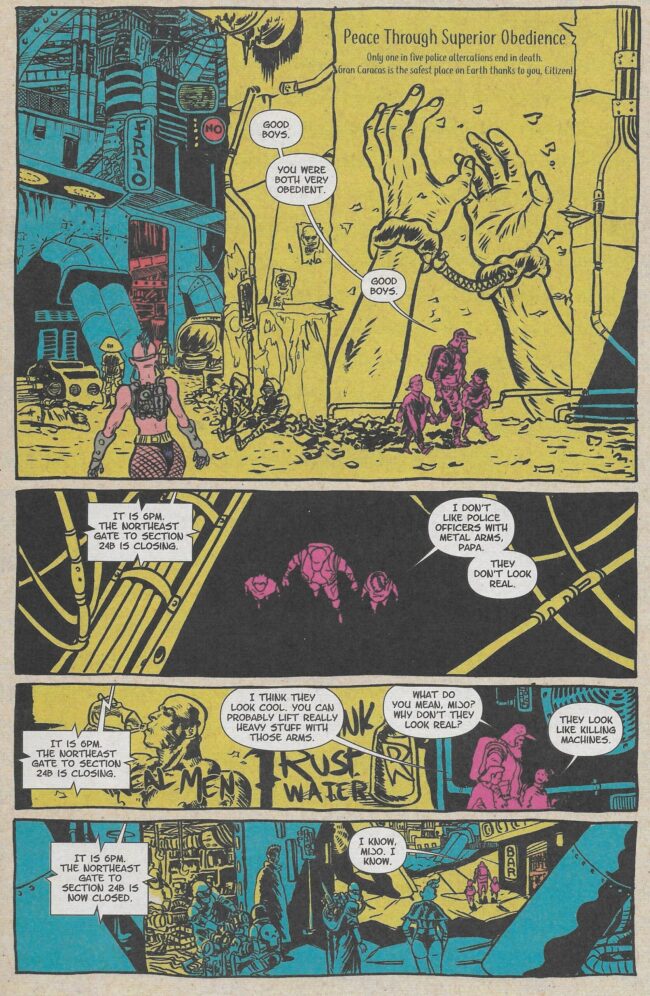

The direness of Night Hunters reveals itself immediately by way of the state propaganda that seems to cover every surface of the city. The state’s effort to indoctrinate the populace is impossible to ignore. But the propaganda machine requires seemingly limitless fuel, and the state’s insatiable hunger for more bodies on its police force is presented to citizens as a path out of their soul-crushing poverty. “Peace Through Superior Obedience” reads a towering poster that centers a pair of bound hands. Juan reflexively echoes the sentiment. “Good boys,” he says. “You were both very obedient. Good boys.” Obedience insures safety, except when it doesn’t. It isn’t long before police violence separates the family and brings Julian to the brink of death.

In a devil’s bargain, Juan trades what little he has to save the boy. This salvation comes in the form of cybernetic enhancement. The procedure does not make Julian whole, however. He is badly disfigured, and his only means of communication is a ghastly clicking sound. “One click for yes. Two clicks no. Are you glad to see your father again, Julian?” the back alley surgeon asks the boy in a heartbreaking exchange. “—Click—” comes the reply as the boy’s artificial eye and teeth glimmer from the darkness. Baker and Ziritt have created a world in which every citizen outside of the police force is inherently criminalized. Everyone is oppressed. Everyone is just barely surviving amid mounting crises and diminishing resources. Everyone is one crisis away from fatal catastrophe.

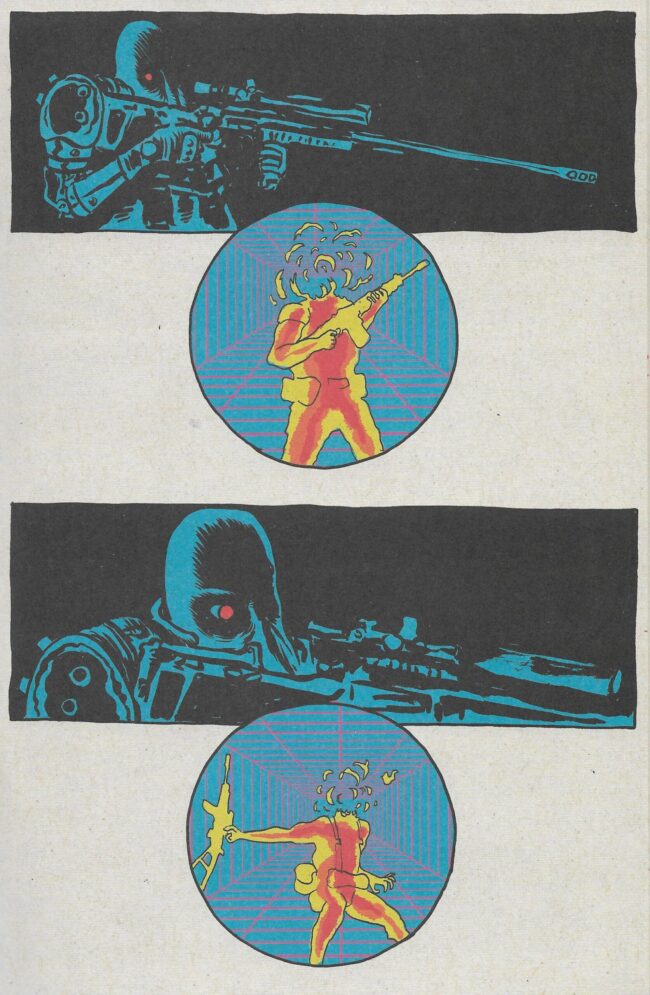

The story advances, finding Julian in adulthood, in service to the police forces. In the intervening years he has acquired a wealth of technical expertise, street savvy, and a menacing new handle. To his paramilitary teammates, he is Sombra, a hooded sniper. His no-holds-barred task force is in pursuit of the benevolent outlaw and local legend Junk Boy. In short order, following some heavy action and a rooftop foot chase, Junk Boy is revealed to be Julian’s estranged brother, Ezequiel. Night Hunters goes on to explore the conflicts between and among these opposing forces, as the brothers must surmise what they are fighting for and where their loyalties lie.

While executed on a sparse, lean scale, Night Hunters is a convincingly rendered, deeply-felt addition to the cyberpunk canon. Ziritt and Baker -- working from a concept first explored by Ziritt and the late Ralph Niese, to whom the book is dedicated -- deliver a more visceral take on the cyberpunk genre than most contemporary conceptions of it. Night Hunters is stripped of the gloss and sheen that often mark current iterations of the genre. The future Ziritt and Baker portray is not honed to a bleeding edge, but heaped and tangled, wrapping everyone in knots from which they try and fail to extricate themselves. For his part, Ziritt evokes claustrophobia and menace by rendering much of the world in monochromatic neon. His broad, gestural approach is short on detail and intricacy, but in trading those away he gets a momentum that really sells the brutality of a bullet to the head or a punch in the throat.

Narratively, Baker’s script is in keeping with the roots of a genre long-known to shine a light on the horrors of unchecked corporate growth and overreach. Privatized forces work in tandem with the oppressive state to insinuate themselves into the lives of every person, invading ever-deeper to enact parasitic relationships from which the citizen cannot withdraw, stripping them of what little they have left. Baker is remarkably effective at making the story relatable by turning the miseries and indignities of the present into the horrors of the future. Those upgrades that facilitated Julian’s survival? “Planned obsolescence,” the back alley surgeon explains. “Every two years or so you’re going to have to come back and see me. We’re going to have to do this dance for the foreseeable future, Juan.”

Neuromancer author William Gibson’s oft-cited observation that “The future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed” holds true in Night Hunters. And it never will be. That’s a feature, not a bug.

Also crowdfunded, but taking a lighter, more playful approach, the self-published one-shot Beef Bros follows Huey and Ajax, a pair of yoked and woke bodybuilding buds as they defend their neighbors from myriad systemically oppressive forces. They are introduced to the reader as many heroes are introduced, intervening on behalf of some poor troubled soul in a back alley. In this case, the poor troubled soul is Nugget, a down-on-his-luck veteran. The menacing figures the titular bros must dispatch are the police who are harassing him. The cops -- rendered gleefully by artist/co-creator Tyrell Cannon as spittle-flecked, goose-stepping, jack-booted thugs -- make no qualms about the fact they are merely defending private property. “You think you can just mooch off society?” a cop asks. “[Y]ou’re hurting business!”

This confrontation kicks off a tour of the stifling forces that constrain and immiserate the working class. The narrative proceeds by way of video game logic as the Beef Bros quip and fight their way through the mid-bosses of modern capitalism. Next, they square off against Ted the Landlord, who is emboldened by the “Crystalline Awareness” technique, which allows him to “justify anything, do anything” in service of growing his business. “I’ve got a right to make a living. And my business is renting out my building," Ted says. “Who are they to say I can’t live my life? Just because they’re too lazy to get jobs?” Sitterson revels in this kind of directness, eschewing subtlety in favor of direct confrontation. While it reads as humor, it is anything but cynical. It is bracing in its simplicity.

The narrative culminates with a throw down between the Beef Bros and their opposites, the Jovian and Sgt. Kilroy. The Jovian, the super-powered emperor of Jupiter is an Elon Musk analog -- “People say he’s the only one who can save us from ourselves!” -- and Sgt. Kilroy is the virtuous embodiment of military service.

Writer/co-creator Aubrey Sitterson is unequivocal and unapologetic in his espousal of a leftist worldview - anarcho-communist, in his estimation. Things do not need to be organized in a way that only benefits a lucky few. That’s a choice that is largely made without the consent of the many, by those few who hold power. The choices that the powerful impose on the working class foster a political climate, a state of mind that can feel inescapable. It affects the smaller choices that many of us make out of habit, or unfamiliarity with any alternative, often against our own best interests for short term gain. For survival, really. “[C]ompetition isn’t the solution to everything. Competition is the solution to very little, other than maybe entertainment, or sports, or something,” Sitterson told me when I interviewed him for The Comics Journal last year. Sitterson bets big that the prescriptivist nature of his script will not be read as condescending, but enlightening. He is preaching to the choir, but he is also attempting to serve up a point of entry for newcomers to the philosophy he espouses. Packaged with a list of recommendations for further reading, it might have been doubly effective.

Beef Bros is a pastiche of aesthetic influences. Pro wrestling, the side-scrolling beat ’em up video games of the '80s and '90s, and shōnen manga can all be seen in Tyrell Cannon’s bold-yet-concise linework. While distinct, these influences do occupy similar space on the spectrum, in that they all explore notions of masculinity and strength. They congeal very well here, thanks to Cannon working in tandem with colors provided by Raciel Silva and Fico Ossio. As a result, the figures have enough weight to give a fairly simple story a sense of stakes, and enough momentum to carry it forward. Tegan O’Neil put it succinctly in her review for The Comics Journal: “The art is immediately ingratiating. Cannon knows how to exaggerate the human form for comedic effect without obscuring storytelling. Beef Bros is colorful in a very contemporary way while also reflecting a debt to the 1980s.”

This bold palette is not just a nod to the source material, but also makes the case that fighting for a more egalitarian world can be a joyous thing. The looping gradient arrows that accentuate Huey’s and Ajax’s muscular forms amid their wrestling acrobatics, for example, pull double duty: evoking both the arrows found in detailed graffiti pieces, as well as the move input diagrams of fighting games.

Night Hunters and Beef Bros say the same thing in different ways: capitalism is making many of our lives miserable, but there is hope in class solidarity. If Night Hunters is a cautionary parable of class solidarity, Beef Bros is a celebration of the same. And while both of these titles succeed in telling their respective stories, it is Night Hunters that hangs together as a coherent, accessible narrative, even if it undercuts its radical vision with a resolution that favors symbolic victory over material gains. Its adherence to genre story structure gives it mainline appeal.

Beef Bros hits all the necessary storytelling beats and hints at further adventures, but it's hard to imagine it succeeding beyond the hyper-focused niche market for which it was created. It’s more akin to agitprop in genre packaging. Still, agitprop plays a crucial role in enacting social change. As a story, Beef Bros is entertaining enough, but it tells more than it shows. That makes it narratively uneven, but persuasively powerful - if the reader is willing to forgive the lack of nuance. “[W]ell-crafted, conscientious genre storytelling can come in, using genre tropes as a Trojan Horse for these big ideas, such that the reader arrives at the ideas on their own. This makes the reader more open to the ideas than if they were merely told them while also allowing the new notions to embed themselves more deeply since its understanding and wisdom the reader earned themselves,” Sitterson told me. He isn’t wrong, and baked into that sentiment may be a deeper truth about what audiences are looking for in their storytelling.

It isn’t news that crowdfunding has become a conventional avenue for making comics. Nor is it news that crowdfunding is no longer an avenue pursued solely by creators, but publishers as well. What feels new is that two titles so boldly critical of capitalism and police forces were successfully funded. It may point to an appetite for socially-conscious genre (and genre-adjacent) comics in the wider market, and more comics that address class struggle instructively and in entertaining ways. With Night Hunters and Beef Bros as evidence of what is possible, it isn’t hard to imagine such a world.