Nick Cardy, best remembered for his artwork for DC Comics in the 1960s and 1970s, died of congestive heart failure on November 3, 2013 at 9:40 p.m. He was 93 years old.

Nick Cardy, best remembered for his artwork for DC Comics in the 1960s and 1970s, died of congestive heart failure on November 3, 2013 at 9:40 p.m. He was 93 years old.

Cardy was known for his classicist approach to the human form and his ceaseless inventiveness. He also drew some of the prettiest girls and young women to appear on a comic book page. Working closely with Executive Editor Carmine Infantino, Cardy became a cover specialist at DC in the early 1970s.

Born Nicholas Viscardi on October 20, 1920, he was the son of Italian immigrants who didn’t speak English. Nick, who shortened his last name after entering the comic book field, grew up on New York’s Lower East Side. His father was a laborer and his mother was a seamstress in the garment district. Cardy started woodcarving, sculpting and drawing at the age of six. When Nick was 14, photographs of his painted murals appeared in the New York Herald Tribune and the Literary Digest. He attended the School of Industrial Arts where he won awards for his artwork, and also took art classes at the Boys Club of America and the Art Students League of New York.

After high school, Cardy worked briefly as an apprentice in an advertising agency, then was hired in 1939 by the Eisner-Iger production shop to draw comic book features. His early work in Fiction House titles included Roy Lance in Jungle Comics and Stuart Taylor in Jumbo Comics. Will Eisner, who split with Jerry Iger to produce a newspaper insert featuring The Spirit, hired Cardy to take over Lady Luck, a four-page backup strip in the insert. Working alongside such stellar talents as Lou Fine, Bob Powell and George Tuska, Cardy produced Lady Luck in Spirit sections dated 5/18/41 through 2/22/42. Eisner became a mentor of sorts. Cardy later described Eisner as, “A gentleman, a creative genius and a wonderful artist. He was a master of dramatic lighting. I believe we were both very much influenced by John Ford’s movie direction and other directors of the era.” Nick also worked for Quality Comics through Eisner, and when permitted to sign his name, used “Cardy” for the first time. Then he left Eisner’s studio to work directly for Fiction House before being drafted into the U.S. Army in mid-1943.

Cardy saw action in World War II as a Sherman tank driver in the European theater, and received two Purple Hearts. Back in New York in 1946, he met and married Ruth Houghty while working as a freelance artist for Fiction House and doing other types of magazine art. He drew the Tarzan daily newspaper strip for Burne Hogarth and Casey Ruggles for Warren Tufts, but the most important career development occurred when he did a six-page backup story titled “Customs Cop” in Gang Busters #6 (October-November 1948). It was his first assignment for DC (then National), who became his principal employer for the next 26 years.

Cardy’s artwork in the late 1940s and 1950s appeared in such titles as Adventures of Alan Ladd, House of Mystery and Tomahawk. He drew all the stories in the short runs of Congo Bill and The Legends of Daniel Boone, and later contributed to My Greatest Adventure, House of Secrets, Tales of the Unexpected and many others.

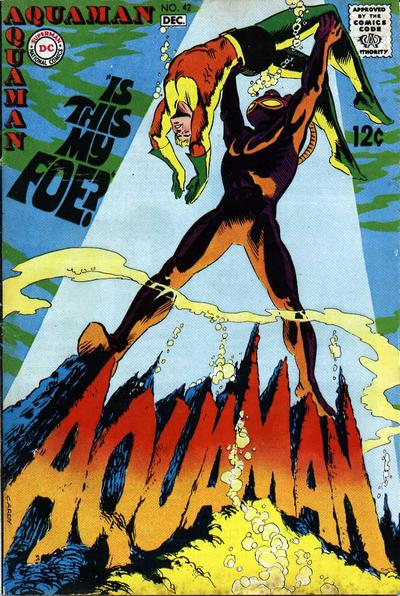

Late in 1960, Cardy worked on the first of his three signature series. When DC began pushing super heroes, they decided to see if Aquaman could successfully star in his own book. Aquaman was created in 1941 by Mort Weisinger and Paul Norris, never rising above second-string status in the back pages of various titles. The first of four Showcase tryouts was drawn by Ramona Fradon, who had been handling the character since 1951. Cardy was given the nod with Showcase #31 (March-April 1961) and the two issues that followed, and associate editor Murray Boltinoff decided he was a perfect fit for the Sea King’s adventures. Cardy proved adept at drawing sea creatures; his fluid, swirling water currents helped create a captivating, eye-pleasing undersea world. When Aquaman received his own title (#1, January-February 1962), Cardy continued as the regular artist. He became a fan favorite, not only because of his superb story-telling ability, solid figure work and facile inking, but because of the way he rendered Mera, Aquaman’s girlfriend. Cardy’s women had curves, not angles, and seemed to exist in three dimensions on the two-dimensional page.

Late in 1960, Cardy worked on the first of his three signature series. When DC began pushing super heroes, they decided to see if Aquaman could successfully star in his own book. Aquaman was created in 1941 by Mort Weisinger and Paul Norris, never rising above second-string status in the back pages of various titles. The first of four Showcase tryouts was drawn by Ramona Fradon, who had been handling the character since 1951. Cardy was given the nod with Showcase #31 (March-April 1961) and the two issues that followed, and associate editor Murray Boltinoff decided he was a perfect fit for the Sea King’s adventures. Cardy proved adept at drawing sea creatures; his fluid, swirling water currents helped create a captivating, eye-pleasing undersea world. When Aquaman received his own title (#1, January-February 1962), Cardy continued as the regular artist. He became a fan favorite, not only because of his superb story-telling ability, solid figure work and facile inking, but because of the way he rendered Mera, Aquaman’s girlfriend. Cardy’s women had curves, not angles, and seemed to exist in three dimensions on the two-dimensional page.

Cardy stayed on the interior art in Aquaman for 39 issues, and continued doing the covers through the end of the series (#56, April 1971). He never stopped trying to elevate his work, until the later covers in the series were among the most striking and imaginative of the publisher’s entire line.

Nick Cardy’s second important series for National was Teen Titans, a group initially made up of Robin, Kid Flash, Aqualad and Wonder Girl. After two try-outs drawn by Bruno Premiani, Teen Titans #1 (February 1966) featured interior art by Cardy, a switch which added immensely to the appeal of the book. He penciled or inked all 43 issues of the series. After Wonder Girl’s origin was belatedly told in #22, Donna Troy’s new costume was shown off on Cardy’s striking cover to Teen Titans #23.

Nick Cardy’s second important series for National was Teen Titans, a group initially made up of Robin, Kid Flash, Aqualad and Wonder Girl. After two try-outs drawn by Bruno Premiani, Teen Titans #1 (February 1966) featured interior art by Cardy, a switch which added immensely to the appeal of the book. He penciled or inked all 43 issues of the series. After Wonder Girl’s origin was belatedly told in #22, Donna Troy’s new costume was shown off on Cardy’s striking cover to Teen Titans #23.

He also worked on other titles at DC. His moody art for the Bat-Squad story in The Brave and the Bold #92 garnered special notice. He told interviewer John Coates, “I was looking for a certain perfection in style. Out of a hundred drawings, I may like maybe four or five. I was trying to draw the women prettier. With some comics work I didn’t get the opportunity to use many shadows and blacks, but with The Brave and The Bold, I had the chance to work on dramatic detective stories and I was able to use a lot of bold blacks. With pen and ink, I can achieve a scratchy, foggy effect that is appropriate. It was a continual process of learning.”

He also worked on other titles at DC. His moody art for the Bat-Squad story in The Brave and the Bold #92 garnered special notice. He told interviewer John Coates, “I was looking for a certain perfection in style. Out of a hundred drawings, I may like maybe four or five. I was trying to draw the women prettier. With some comics work I didn’t get the opportunity to use many shadows and blacks, but with The Brave and The Bold, I had the chance to work on dramatic detective stories and I was able to use a lot of bold blacks. With pen and ink, I can achieve a scratchy, foggy effect that is appropriate. It was a continual process of learning.”

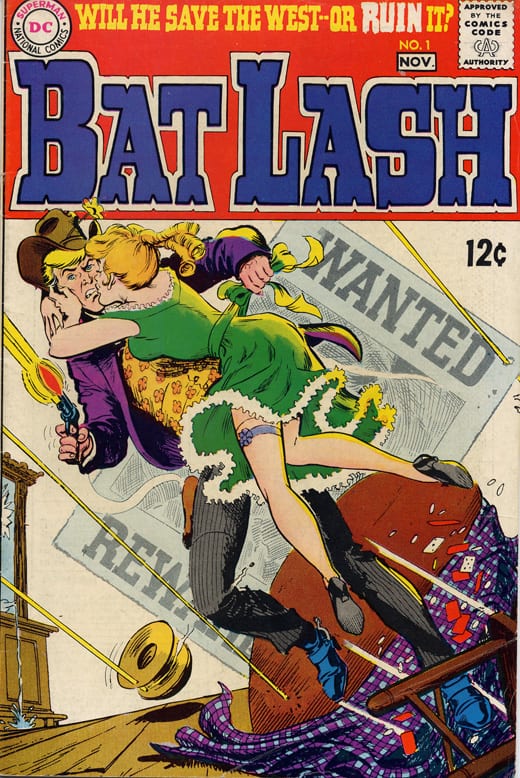

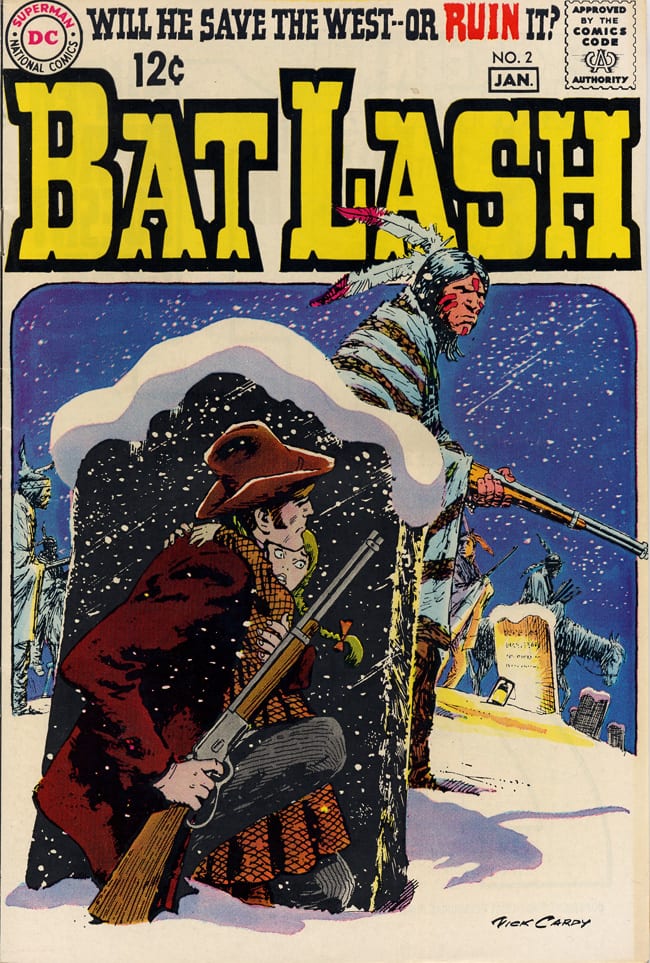

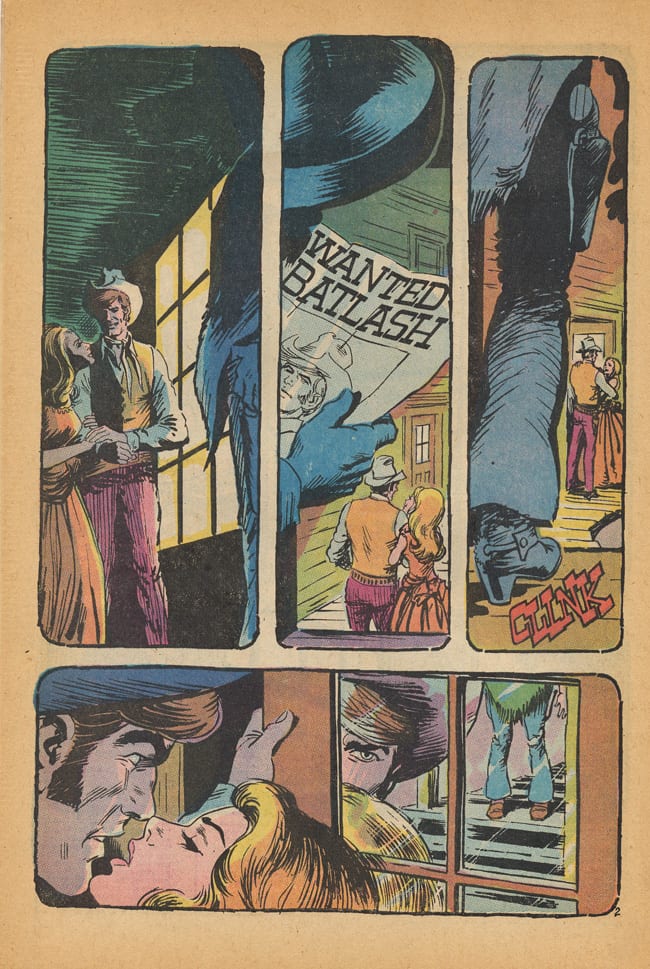

Probably Cardy’s most critically lauded work was for the Bat Lash series from DC, launched in Showcase #76 (August 1968) and Bat Lash #1 (November 1968). The unorthodox Western series was conceived by editorial director Carmine Infantino, editor Joe Orlando, former editor Sheldon Mayer, and cartoonist Sergio Aragonés. The protagonist of the tongue-in-cheek series was a self-professed pacifist, ladies’ man, and gambler, so Cardy adopted a looser visual style to better accommodate the pronounced humorous elements in the book. (Some have compared it to the James Garner episodes of the TV series Maverick.) The stories, dialogued after the first issue by Denny O’Neil, were engaging, and immeasurably enhanced by Cardy’s inventive story-telling techniques (experimenting with the way the pictures flowed from panel to panel) and expressive inking. Produced when Cardy was 48 years old, Bat Lash benefited by work by an artist with decades of experience, who was also able to bring a remarkably youthful spirit to the pages. It represented a creative peak, and cemented Cardy’s position as an important interpreter of the sequential art form. Unfortunately, even a re-invigorated Western couldn’t revive the genre. Less than stellar sales forced the cancellation of Bat Lash with its seventh issue, dated November 1969.

Probably Cardy’s most critically lauded work was for the Bat Lash series from DC, launched in Showcase #76 (August 1968) and Bat Lash #1 (November 1968). The unorthodox Western series was conceived by editorial director Carmine Infantino, editor Joe Orlando, former editor Sheldon Mayer, and cartoonist Sergio Aragonés. The protagonist of the tongue-in-cheek series was a self-professed pacifist, ladies’ man, and gambler, so Cardy adopted a looser visual style to better accommodate the pronounced humorous elements in the book. (Some have compared it to the James Garner episodes of the TV series Maverick.) The stories, dialogued after the first issue by Denny O’Neil, were engaging, and immeasurably enhanced by Cardy’s inventive story-telling techniques (experimenting with the way the pictures flowed from panel to panel) and expressive inking. Produced when Cardy was 48 years old, Bat Lash benefited by work by an artist with decades of experience, who was also able to bring a remarkably youthful spirit to the pages. It represented a creative peak, and cemented Cardy’s position as an important interpreter of the sequential art form. Unfortunately, even a re-invigorated Western couldn’t revive the genre. Less than stellar sales forced the cancellation of Bat Lash with its seventh issue, dated November 1969.

Along the way, Cardy’s stock at DC had risen considerably. Joe Kubert later said, “In the late 1960s I was editing at DC while Nick was doing Bat Lash and various projects for DC. Everyone, and I mean everyone at DC was talking about his work. The figures, composition, his layouts, the impact his covers had, everything about his work is tremendous! Nick is so original in his concepts. I can’t think of an artist that knows Nick’s work and is not impressed by it.”

Along the way, Cardy’s stock at DC had risen considerably. Joe Kubert later said, “In the late 1960s I was editing at DC while Nick was doing Bat Lash and various projects for DC. Everyone, and I mean everyone at DC was talking about his work. The figures, composition, his layouts, the impact his covers had, everything about his work is tremendous! Nick is so original in his concepts. I can’t think of an artist that knows Nick’s work and is not impressed by it.”

Chief among them was Infantino, who gave Cardy the job of primary cover artist for the publisher’s titles (sometimes working from Infantino’s layouts) in the early-to-mid 1970s. His ability to draw attractive women made his numerous covers for the DC romance titles of that era worth more than a second look, appearing on such books as Heart Throbs, Girls’ Romance, Girls’ Love Stories, Falling in Love.

In late 1974, either due to business disputes or boredom with comics (depending on the source), Nick Cardy left comics for the commercial art field, signing his name “Nick Cardi” on those new endeavors. He produced ad illustrations, magazine art and movie ad art (not necessarily posters) for such films as diverse as Neil Simon’s California Suite (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). He later commented, “My work has always been challenging. I’m not only a frustrated illustrator, I’m also always looking for perfection. My career has always been phases: I got into comics, went into advertising, and finally did movie posters. The comics were my training ground.”

Nick and Ruth Cardy divorced in 1969, but remained friends. Their son Peter was born in 1955 and died in 2001. In 1998, Cardy was a Guest of Honor at the Comic-Con International in San Diego, after passing on the honor for years. He was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2005, and was the subject of two books: The Art of Nick Cardy (Coates Publishing, Inc., 1999) and Nick Cardy: Behind the Art (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2008).

Quotes are from The Art of Nick Cardy.