Only a year ago, I wouldn’t have been able to recognize Badiucao from a photograph for our meeting; his identity was still a secret. Even now that it’s been revealed, he didn’t offer his real name and I didn’t ask. Badiucao is the pseudonym of a prolific political artist and Chinese dissident – though he’s at pains to say he’s now an Australian, too. (“I’m Aussie, mate!” he says of his new home.) His current daily ritual is to get out of bed and draw in response to overnight news from the Hong Kong protests. These pieces are then often displayed in the protests the following days. We talked about responsibility, censorship, and the decision to show his face. - Martyn Pedler

When a pro-democracy politician had his ear ripped off in a mall in Hong Kong, it provoked two new pieces of art from you. Can you talk me through them?

When a pro-democracy politician had his ear ripped off in a mall in Hong Kong, it provoked two new pieces of art from you. Can you talk me through them?

I am very strongly inspired by whatever has been circulating online associated with the Hong Kong protests. A thug – he could be a member of Triad, I don't know – apparently got into an argument with pro-Hong Kong democracy protesters in a shopping mall then just snapped and started to attack people with a knife. That is why I suspect he might be a member of a Triad, because no normal person would carry a knife in a shopping mall for no reason. Then he attacked people until he was restrained by security. This council candidate came and tried to stop him during this incident. The thug bit off the man's ear. There was video circulating on Twitter and one of the screenshots was just the moment he bit off the ear. That became the icon for the whole thing. It tells exactly what is happening, which side is civilized, which side is barbaric.

But, of course, it was a very graphic image to circulate, and in order to tell the public the story without getting too much of the disturbing feeling, it's necessary to make a spin on it and that is why I created this first image. I replaced this thug with Winnie the Pooh, and exaggerated a real bear with force and violence. Art has this power to tell truths behind facts, and this violent person is just the face of the authoritarian tyranny from Beijing. By bringing back Winnie the Pooh, which is a symbol for President Xi Jinping, it’s telling the people what’s really going on. This is a juxtaposition with a cute version of Winnie the Pooh and this violent bear, but also a juxtaposition between the leader from Beijing to the soldier of his evil force in Hong Kong. It’s a fast and raw reaction.

After that, I did one featuring [Hong Kong leader] Carrie Lam and her new jewelry collection, adding the necklace of a bitten-off human ear. Compared with the first work, this is more a metaphorical way to do it. You don't see it as particularly confronting until you realize the detail. I also added an eyeball to her ring, symbolizing another famous case when the police were shooting tear gas right in First Aid people's eyes during the Hong Kong protests. So these two pieces of human flesh become the symbol for the whole movement, showing how much risk and danger the protester or the journalist or First Aid have to go through almost every night of the last five months. I like to depict the face of a leader like Carrie Lam as, in a practical way, it empowers people. Gives people an alternative way apart from violence. You can strike back using art. You can mock them. You can make them look ridiculous, absurd, cruel, whatever they try to hide in the media. Using art, you can show their true faces.

Some people say, "Oh, I just create art for myself" or "I don't think about my audience", but your art – you want it to have a practical effect.

Some people say, "Oh, I just create art for myself" or "I don't think about my audience", but your art – you want it to have a practical effect.

Exactly. I mean, sometimes people might say I'm trying to meet my audience within the protesters, but also, the ones who I'm criticizing are also my potential audience. They're probably my priority. I want them to see the work as if they're looking into the mirror and see the truth of themselves. Maybe that would change them, or at least make them uncomfortable, which is one of the most important things to me.

I guess your question is that a lot of people say art is for the sake of art, or art is for internal exploration. I do not deny that art always performs in that way and to some extent, it’s the same motivation for me – but it's reflecting my experience of being me and interacting with the world. I was born in China, a country that tries to take away all political discussion from daily life while, on the other hand, hugely oppressing people politically. This is my life experience and my art is merely reflecting on this experience. It makes me understand more of the people in Hong Kong as well. They're oppressed by the same force in Beijing. I absolutely understand them. So I extend myself, allow them to come into my heart, and then I start to make work not just for me but also for them, because we are commonly experiencing this terrible oppression from one authority.

I never want to deny the social responsibility of an artist because I believe responsibility should come with power. As artists, we definitely have this magic power and we can potentially influence a lot of people, not just entertain ourselves. When we're talking about artist, we can't talk about him or her without including that we're exhibiting our work in whatever venue. It could be online. It could be a gallery show. It could be social media, and that's a huge impact. With this reality, I think it is very selfish for anyone to say, "I'm just doing it for myself." This is just not possible. Even by saying so, it's just a different kind of political statement.

We are free to do whatever we want and we should use this freedom for social struggle. Especially given that we are now in what could potentially become another Cold War situation. In the trading of the so-called West and China, because there is a fundamental political difference on human rights. That's very critical and urgent. We're also facing problems like the environmental crisis. We're facing the problem of Trump's presidency. We're facing the problem with Brexit that endangers the whole EU’s stability and a lot of other things, like the refugee crisis and Middle East turmoil.

All of this should be a wake-up call for my fellow artists around the world. It is time for us to pay more attention to what is going on. I think being political is not the problem. The problem is if your political message is not specific enough. This is my problem with, I guess, the mainstream political artists, artists like Banksy. A lot of his work ended up with this broad idea of, "We want peace. We want love." I think his most powerful work is when it's really specific. When it's about human rights, when it's about advocating for the Kurdish artists who got repressed by Turkey.

Is there an emotional cost to being political? Does your art come from a place of anger, say, rather than playfulness? Or is it both?

I think I will leave this question to the audience. I mean, it would be very subjective for me to say. If I still see people laughing when they see my work, I think it’s okay. Of course any work comes with sensitive emotions of the artist. It's part of the work as well. But I don't think anger is really the right emotion to describe me when I'm creating. Being playful is important within my work, not just political work, but also for my whole art practice. Some artists serve as a magician, and that’s the trick – you get the audience to look at your work and ask questions. But what I want to emphasize is that, while the trick is important, so are the questions you want the audience to ask. As artists, we're not politicians. We are not obligated to give a solution to problems. We do have this duty to ask questions in front of the public and let them come up with better solutions to address those problems. But this should not come from pure anger. This should coming from a broad understanding. It's about putting myself into a situation with those who are oppressed, and to try to be a voice for those who do not have a voice.

You talked about responding to the news cycle. You obviously work fast, and you’re very prolific. But do you ever look back and go, “I wish I had a few more days?”

Well, I guess I never see my cartoons or drawings as the end of the whole process. I would rather say they're just my visual journal. My struggle here is that I see myself as an artist and a political cartoonist, at least equally, but I haven't gotten a chance to exhibit my work and to prove myself to different genre or venue. The way that I work is I closely follow the news and do quick work addressing whatever happened and put it online. I will always come back to work like that. They're like the landmarks, the pins on the timeline, that I can trace back to see the incident or the topic that I was interested in. But one way that I develop work for gallery practice is I will try to bring the political cartoon to sculpture.

For one example, I did a very quick sketch for Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia. [Liu Xiaobo] is a Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner who passed away two years ago. Before he passed away, I did a drawing of a photo that went viral after his cancer was diagnosed in the terminal stage. He'd already been in prison for several years. There's a very limited visual reference of him. So this one particular photo of him and Liu Xia, his widow, got really circulated inside China, and outside, because it is probably one of the first photos of him for maybe five years or even longer. Unfortunately, censorship in China quickly sees that as a threat and deleted it.

My reaction is to kind of recreate this image but in a very abstract or simplified way. It can lay low to go around the censorship but also giving people enough indication that this is a work for them. Within that photo, Liu Xiaobo was wearing a hospital uniform with these stripes, and Liu Xia was wearing an orange top. I simply traced their outlines. It's just stripes and the orange color blocks symbolizing them, and suddenly that work becomes a new icon when others of their photos are deleted. You see, this is almost like a war. My understanding of censorship makes it possible to create work like that but still maintain its function and maintain its efficiency for spreading the message.

It does not just stop there. I transformed into street art. I made it into post-up work in Hosier Lane in Melbourne. The very day after Liu Xiaobo passed away that artwork became a memorial site for him. People started to bring flowers, cards, candles. It surprised me, I never expected it to happen. There's things being put up and covered up in Hosier Lane almost overnight. That work, it was there a month or even longer because people continued to contribute flowers, their own artwork, and letters. That inspired me greatly. I kind of rearranged the work and made it downloadable for everyone around the world. We had six major cities including New York that joined us to do the same street art. That's the evolution from online work to the real world.

Back to your question. Yes, it is always just a beginning when I draft, but it will not stop there. I always look for new inspiration from these old works. The limitation for cartoons is you have to do it fast, which means you can't do it very deeply. There's no experiments that you can do within it. But when you've got time to revisit them, that's when you can make it a living work that's ported into different space.

Does knowing that your work is going to be reproduced as protest signs in Hong Kong change how you approach the art itself?

Well, sometimes one thing is I don't particularly like is putting words in my work. I want my work to communicate with different people, not just the protestors, but also the people inside and outside of China. People who do not read Chinese or who do not read English. I believe that visual language has this magic to bonding and bridging between different understandings. Now sometimes, I will include some of the slogans that are used in Hong Kong like BE WATER or HONG KONGERS FIGHT BACK. Just so when people are downloading it and printing it out for a protest when they're demonstrating it, will make more sense. I guess that's my compromising a bit. It’s almost like a film poster. Also, if you go through my work, you’ll see most of them are portrait ratio, instead of landscape, because I know most of my audience are from Twitter or Instagram. That’s why I always design it to fit into our little screens.

I was reading about your grandfather, who was a filmmaker killed in China’s anti-intellectual crackdown. What were his films like? Have you seen them?

I was reading about your grandfather, who was a filmmaker killed in China’s anti-intellectual crackdown. What were his films like? Have you seen them?

Actually, they're on YouTube! There are several. I wouldn't say he got into trouble because he was a dissident artist. The pathetic thing is that he got into trouble just because his work was not 100% propaganda. Everyone in China during that time was making work praising the communist party. In the beginning, believe it or not, the idea was from the left, especially for artists. They fantasized about the promise from the communist party in China. [My grandfather’s] major problem was because his work was trying to bring a bit of humanity to the heroic communist party member. Basically, a story will be like Titanic. A hero is on the Titanic but, according to Beijing, he has to be brave. He can't show hesitation. You can't struggle, even if you're going to die. My grandfather was trying to make the film in a more humane way. Bringing in struggling, bringing in hesitation – but also overcoming the hesitation. He believed that's how you make it more convincing to the people. Apparently, this did not fit the party standard. You have to be a robot. This is their tragedy. This tragedy does not just belong to them alone. It belongs to the whole generation of intellectuals and artists and it's continuing, generation after generation. Now it’s passed on me.

He decided to stay in China. You decided to leave. Was that a big decision or a foregone conclusion?

They started filming even before [the] Communist Party were in power. They had become top people in the industry. In other words, they had a chance to leave China – but they choose not to because, as I said, they believed in communism like a lot of artists and intellectuals. It took real luck and, of course, knowledge to make the right decision. Apparently, my family, they didn't make a good decision. As for me, my whole family learned from this and they still saw very much that China is the same China. They saw me wanting to be an artist just like my grandparent, and that generated my decision to leave.

It was only this year that you came out publicly for the documentary China’s Artful Dissident. What made you decide this was the time to reveal your face?

I shall not say it was a decision purely of my own judgment. It was more like a chess game that I played from the very beginning of my art career. I knew once my identity was compromised it means a huge risk, not just to me but also to my family, to anyone who's helping me. I'd been anonymously working as an artist from the very beginning, but at the end of last year, something happened that compromised my identity.

It happened three days before my Hong Kong solo art exhibition. I was contacted by my family in China and told that police had taken one of my relatives to the police station for interrogation because of my art practice. And also because of my upcoming art exhibition in Hong Kong. The message was very clear – they wanted the show to be canceled. Otherwise, there would be bad consequences for me and my family. That was just three days before the opening. It left me no time to really deal with it. Then the very next day another relative got approached by the police, and the same thing happened. The tactic of the policemen is that they're just going to knock, door by door, until it breaks you down. It’s quite an efficient tactic. They say they’re also going to send two policemen from Shanghai to Hong Kong. If I chose to continue the show, it posed a huge threat to everyone who's helping me. Eventually, a decision is made to cancel the show.

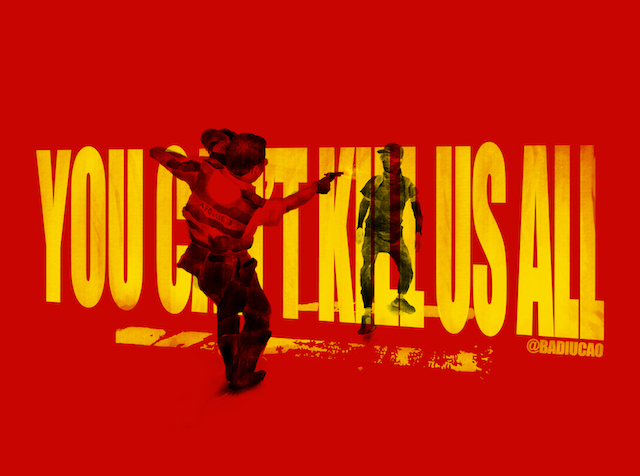

But it’s not just about the show. It’s also about all those years being anonymous as a layer of protection. Now it’s no longer there, what is my strategy? How do I deal with this? How can I protect my family and myself? You see my decision. That is why I chose to reveal myself. If I’m going to do it, I better announce myself on a big platform and on the right date – the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. This decision was not easy. There is no guarantee it will bring me safety. Now my strategy is that I want to tell the Chinese that their intimidation is not working. I will not cave in and give up what I cherish as an artist. But also, I want to tell the world that we should not back off when these things happen. It puts me in a better position to criticize let's say, Blizzard [Games], the NBA, all those big companies. If an individual artist can do it, what makes you a coward? Ultimately, what you're doing will harm you in the long term. It may be short term economic profit, but what about the future?

Anyway, back to the decision. Now, because I confront them face to face, I'll be more open for interviews like this one. I'll be more open to meeting people, making connections and receiving support and help. I don't know if this is 100% successful in terms of protecting myself, but at least I am free and that is a really great feeling. Free with fear!

What’s your greatest frustration with how the West perceives the Hong Kong protests?

I think the perception of the protests is invaded by this idea that it's all about violence. It's a complex issue. The people who are outside of Hong Kong can only see what is happening via media. I know media are trying their best to bring the reality to the audience outside of Hong Kong, but sometimes the media are also restrained by their own features. They are still audience-centered work. To be more specific, in the very beginning for the media it's excellent to see a million people on the street in peaceful demonstration, but after five hours it becomes really boring to see that on TV. I was doing a kind of world trip recently, trying to promote my documentary, and also to introduce the Hong Kong situation wherever I go. The one thing that I always do is I watch the local news, how they're reporting Hong Kong but unfortunately I would say maybe 50% of the time it will be about violence. That's just the fashion of news.

I mean, come on. Two million people are doing peaceful demonstration and the police are beating people all the time! We have maybe hundreds of front-line young kids trying to defend those people who are marching peacefully. Of course, they're going to use force in some situations. If the media only focuses on that, it creates a general impression of the whole protest. That frustrates me the most. The more you show, the more the world misunderstands Hong Kong. It makes a very vicious circle, sending the message to the people in Hong Kong, “Peaceful demonstration is not working. We can't rely on international support, because they don't really care about us. They only read us wrong. They see us as riots." Then how would it end? It’s not good.

Ultimately, it will not just stay in Hong Kong, because it's about Beijing and Beijing's plan is not just within its own territory. You can see in the South China Sea, you see how it’s threatening all those countries. Not mentioning the interference that China has been throwing in Australia, in New Zealand. The West has this wrong perception, not just of the Hong Kong protests, but of China in general. I think the Chinese propaganda machine did a very good job of rebranding the modern image of China. A lot of people are normalizing China, instead of saying China sits in Beijing’s authority. They see them as any other government in the free world, which is completely wrong. When you're doing that, it will fail every individual in China, and also every Chinese descendant in Australia as well.

I guess the other problem is more subtle. The Chinese government is really good at accusing others of racism when it’s dealing with criticism. That will probably silence a lot of people who are left wing. People here in the western world have to see there's a difference between criticizing the country and criticizing every individual from that country. I don't think it's very hard to distinguish. I think there's a principle that we should defend – that we have the right to criticize China's government, especially because of its awful human rights record. We shall not silence ourselves worrying about being called racists. I want to see more people from the left coming with compassion to the minority, coming with a strong spirit of defending fundamental human rights. Throwing away this concern of, "I don't want to be seen as a racist because the Chinese government says so." The Chinese government do not decide whether you're a racist or not. Chinese people do.

How do you stay hopeful for the role of art in changing the world?

How do you stay hopeful for the role of art in changing the world?

I don’t like the word “hope”. I guess my personal hero would be like Sisyphus, being punished to push a huge rock up the mountain and that rock being doomed to fall down. It seems like my position, or like anyone who's in a similar situation in dealing with the rise of mighty Beijing government. If I only rely on hope, it is very hard to continue on because it will be a very long term fight. My understanding is that hope is established on expectation of success – but what if you can't see success clearly? Then it shakes your belief. Hope becomes toxic. I try to avoid a world of hope. As an artist, I see the beauty of resisting itself. The purpose is not achieving. The purpose is doing.