Don Draper: “In Greek, ‘nostalgia’ literally means ‘the pain from an old wound.’ It's a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone.”

1.

In 1992, I was dawdling my way through a Ph.D. program in English at the University of Illinois. I had trouble focusing on my work that year, because back in my hometown of Buffalo, New York, my mother was dying of cancer. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1985, while I was still living at home but poised to start graduate school at Illinois in the fall. When my parents told me about the cancer, I said that I wouldn’t go to graduate school, that I would stay and care for my mom, but they said “No.” They were insistent that I begin my adult life and career, and they also realized that my offer to remain in Buffalo was based as much on my fear of an unknown direction for my life as it was in some sort of noble self-sacrifice. In retrospect, I’m incredibly grateful that they exiled me from home.

While I studied (and partied) in Illinois, my mom underwent several bouts of radiation and chemotherapy. One breast was removed, then another. I went home when I could, which wasn’t often, because I didn’t own a car and couldn’t afford the time and money that the one-way 16-hour bus ride from Champaign, Illinois to Buffalo required. (The half-hour stopovers at the Cleveland bus terminal at 3am were sad and grimy.) By 1990, though, I’d started dating Kathy, the woman I’d eventually marry, and she’d graciously loan me her car (a hand-me-down from her own parents), and I’d speed down I-90 and visit mom and dad more frequently. Every time I went home, mom looked frailer, more diminished, and more folded-in on herself.

In December 1992, I charged an airplane ticket, flew from Chicago to Buffalo, and stayed with my parents for the Christmas holidays. A few weeks earlier, my mom had lost the use of her left arm. The nerves in the arm had been decimated by repeated radiation treatments, and, according to her doctors, were beyond repair. My mom cried every time she couldn’t do a task with her single functioning arm. She wept when she couldn’t make a cup of coffee or fish keys out of her purse.

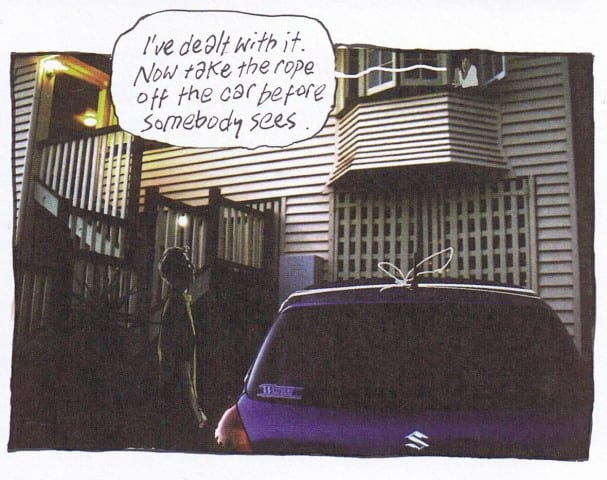

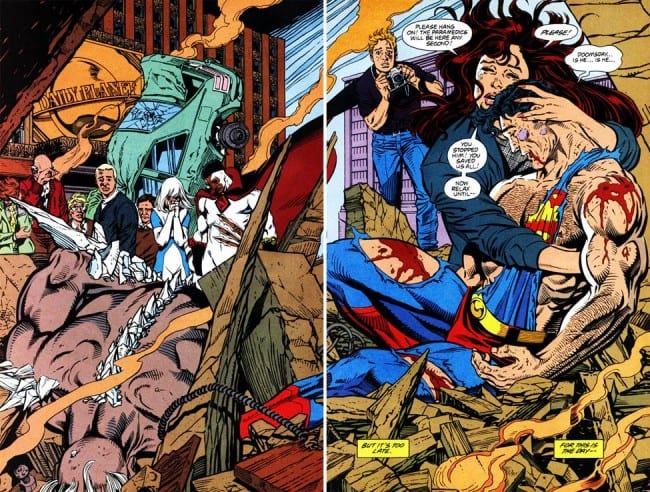

On Christmas Eve, we exchanged presents. I bought my parents a microwave, thinking that it would make it easier for my mom to cook one-armed, and she was ecstatic. Then mom and dad handed me my gift: the deluxe, polybagged version, complete with black armband, of Superman #75 (January 1993), the infamous “Death of Superman” issue. Of course, my parents knew that I read comics—though they didn’t realize that by 1992 my tastes had migrated to Eightball, Hate, and other black-and-white alternatives—and they saw and heard the publicity barrage surrounding Superman’s death. On the day the comic came out, my dad drove my sick, frail mom (who never had a driver’s license) to a local shop, where she stood in line for two hours (mostly with investors, I think) to get a copy.

After the holidays, I flew back to Illinois, and returned to Buffalo one more time before my mom’s death in April 1993. I still have that copy of Superman #75, worthless because I ripped open the polybag and read the comic inside. Occasionally, I’ll remember the image at the finale of that comic, of Lois Lane holding the dying Superman in her arms, and I’ll smile. In the last two years, both of Kathy’s parents have died, and I told her the cliché “You’re never too old to be an orphan,” and that’s absolutely true.

2.

In 2001, my four-year-old son Nate accompanied me on my weekly trips to the comics shop. I felt guilty picking up a stack of comics for myself (and nothing for him), so I got into the habit of buying him a comic that he’d choose from the all-ages rack. During one of our visits, Nate picked out DC’s Looney Tunes #75 (April 2001), and I read this comic out loud to him when we got home.

The story in Looney Tunes #75, “A Hare Gone Conclusion,” written by Dan Slott, penciled by Dave Alvarez, and inked by Mike DeCarlo, is a film noir parody, where Daffy Duck plays a detective investigating the disappearance (and presumed death) of Bugs Bunny. (Slott is clearly riffing off the animated cartoons where Daffy tries and fails to fill a heroic adventurer’s role, such as Deduce, You Say! [1956]—where Daffy plays famed sleuth Dorlock Homes—and Robin Hood Daffy [1958].) In Slott’s story, detective Daffy begins by interrogating the suspect most likely to have killed Bugs, Elmer Fudd, and Daffy’s interrogation segues into Slott’s spin on the “rabbit season/duck season” cartoon routines:

This is an interesting gag to explain to a four year old. As I recall, I told Nate that Elmer “kissed” Daffy (obvious from all the lipstick marks), and vowed that I’d show Looney Tunes #75 to Nate again when he’s a teenager (which I have). Clearly, though, more than smooching went on: Daffy is roughed up in that last panel on page two, and it’s impossible to miss Elmer’s fey facial expression and effeminate gestures.

Slott’s joke seems wildly transgressive, but it’s actually a logical extension of the fluid sexuality in the original Bugs Bunny cartoons. In his article “Bugs Bunny: Queer as a Three Dollar Bill” (1993), film critic Hark Sartin argues that Bugs’ proclivity for drag (as in his show-stopping performance as Brunhilde in What’s Opera Doc [1957]) is only one symptom of the general queer aesthetic of the Warner cartoons, present even in the earliest Bugs shorts. Sartin describes A Wild Hare (1940), the first battle between Bugs and Elmer, like this:

Bugs quickly established a playful sexual innuendo in his dealings with Elmer. When Elmer points his gun at Bugs’ rabbit hole, Bugs’ gloved hand reaches out and strokes the gun. And strokes it. And strokes it. It’s just a little too much. This leads to an extended tug of war, with that big gun of Elmer’s going in and out of Bugs’ hole, in and out, in and out. Later, when Bugs comes up from behind and covers Elmer’s eyes to play “Guess Who?” Elmer comes back with “Heddy Wemarr? Owivia de Haviwin?” Bugs responds to these charming misapprehensions by planting a big kiss on Elmer’s lips.

Slott’s script for Looney Tunes #75 also plays off other elements of the Warner Bros. universe besides its polymorphic sexuality. There’s a pointed joke about mounting Buster Bunny’s severed head, and cameos by obscure characters from the cartoons, including Hassan (“Chop!”), Gossamer and even the unshaven caricature of Humphrey Bogart. This comic was fun to read out loud; I loved reading to my son.

Twelve years later, Dan Slott still tinkers with corporate-owned characters (still to controversial effect), while Nate and I (and Kathy and my daughter Mercer) went to our first gay wedding last September. Life and love’s pulse: in and out, in and out.

3.

Last semester, I taught a class on comics and graphic novels to college sophomores. I’d taught this class before, but I always change the syllabus around from semester to semester—I don’t want to get into a boring routine. In revising my syllabus for fall 2012, I decided to foreground serialization as one of the major topics of the course. I added new assignments and readings that addressed the history of the comic book as periodical, and replicated (as well as I could) the experience of reading stories in spaced-out, floppy-sized chunks.

There were several comics I assigned to teach serialization, but central was all thirty issues of Grant Morrison’s Seven Soldiers project (2005-06). Seven Soldiers consists of three parts: (1) a single comic (Seven Soldiers #0) that established the series’ premise, an invasion of Earth by fairy folk called the Sheeda; (2) seven 4-issue miniseries featuring DC Comics B-listers (including Kirby characters like Mister Miracle and Klarion the Witchboy) moving through individual plotlines and overlapping with the events of the Sheeda invasion; and (3) a final issue (Seven Soldiers #1) chronicling the roles each of the seven characters play in defeating the Sheeda (although the seven heroes never coalesce into a super-team like the Avengers). Seven Soldiers is both a challenging modular puzzle and an exhilarating experience: the more issues you read, the more connections you can trace among the seven series (“Hey, isn’t that Shining Knight in the foreground of this panel from Frankenstein #4?” “Hey, aren’t all these characters dealing with absent fathers and authority figures?”) and the more complete your understanding of the Sheeda storyline. Given the complexity of Soldiers, it was helpful that there were at least two superb exegeses of the series, Douglas Wolk’s chapter on Morrison in Reading Comics (2007) and Marc Singer’s chapter on Soldiers in Grant Morrison: Combining the Worlds of Contemporary Comics (2011). I shamelessly borrowed from the insights of Wolk and Singer in putting together Soldiers lesson plans.

To make my students read Soldiers serially, I put multiple copies of all thirty individual issues on reserve in our university library, with instructions to circulate only three issues per week, in the order that the comics were originally for sale in comic shops. The first week, my students read Seven Soldiers #0, Shining Knight #1 and The Manhattan Guardian #1, and then paused until the next week, when Zatanna #1, Klarion #1 and Shining Knight #2 would be available at the library, and so on. Students could cheat—they could’ve bought or downloaded trade paperback collections of the entire series and read ahead—but judging by our class discussions, most stuck to the “to be continued” plan.

Other parts of the serialization focus: near the end of class, my students read Fantastic Four #44-67, the best Lee-Kirby-Sinnott issues and a key example of comic-book soap-opera serialization. The Fantastic Four was followed by examples of Jack Kirby’s Fourth World comics, which allowed me to talk about creators’ rights, and about Kirby’s influence—appropriate, since Kirby’s technique of splitting the Fourth World mega-story across four separate titles was clearly the inspiration for Morrison’s Soldiers design.

How did my unit on serialization go? Terribly. Choosing Soldiers as a semester-long text was a lousy idea. It’s too stuffed with superhero arcana, too dependent on prior knowledge of DC continuity history. (One of the climatic beats of Seven Soldiers #1 involves a villain named Zor being “sewn,” i.e. changed, into Cyrus Gold, a child murderer killed by an angry mob and then reanimated as the zombie Solomon Grundy. None of my students understood this, and I barely remembered Gold myself.) I also assumed that the students would be interested in superheroes, which was untrue: they like superhero movies, possibly because the property destruction inherent in the genre makes for dynamic summer spectacles, but they found the comics much less of an immersive experience. Their most common complaint was that the ads in the individual comics kept breaking up the flow of their reading.

I also think serialization is increasingly irrelevant in 21st century media culture. In comics, floppies sell less as more readers “wait for the trade” and a coherent narrative arc. Television viewers ignore a program when it airs, opting instead for downloads and DVD collections that allow them to control when and how often they watch their favorite shows. (Some students will binge on a whole season of Lost or Justified over the space of a weekend.) Even though some movie franchises follow an episodic release model—“We’ve got to wait a year for the next Hobbit?”—many foreign and independent films open in theaters and on video-on-demand on the same day. One of the credos of the digital revolution is I want what I want when I want it, and my stories about waiting for my favorite serialized comic books to appear on drugstore spinner racks must sound to my students like a message in Morse code.

There’s a moment in Seven Soldiers #1 where many of Morrison’s narrative threads converge: while releasing a powerful mystic being out of a mason jar, the magician Zatanna screams “Ekirts sreidlos neves!” (“Seven Soldiers strike!”), as she activates the hidden machineries of Morrison’s world to defeat the Sheeda:

Tellingly, Zatanna stares directly at the reader as she casts her spell. In issue #4 of her miniseries, Zatanna breaks the “fourth wall” of the comics panel with a direct appeal for help from readers, and she does so again here, asking us to mobilize the connections we’ve built up while reading the comics to interpret Soldiers’ esoteric finale. Morrison invites us to figure out how and why the “Seven Soldiers strike,” but by the end of the semester, my students’ turned down his invitation—they were tired of superheroes, tired of Morrison’s narratives of transformation, tired of the class, and probably tired of me.

My ostensible reason for teaching serialization in the first place was that I felt an obligation to discuss the history of the floppy, but my students don’t care at all about that history—they read comics in the book-length graphic novel format, they never buy comics from a Direct Market shop, and they laugh at the knotted continuities of the DC and Marvel “universes.” Maybe my real reason for teaching serialization is that I still give a shit, even though I’ve supposedly preferred alt-comix over mainstream comics for a long time. Maybe like too many fans of my generation, I’ve given in to nostalgia—and I wouldn’t be the first on TCJ to do so, given how often the Lee v. Kirby debate rages in comments forty-plus years after the damn comics were published. And is it nostalgia when I connect specific comics (like Superman and Looney Tunes) to the memories of events from my personal life? Is it healthy?

4.

On Halloween, my kids and I went to our local comic shop, and picked up several of the free comics distributed as part of “Halloween ComicFest 2012.” Some of these giveaways were fun, and others less so, but one particular single-pager might’ve disabused me of my nostalgia permanently. Marvel offered a combination Ultimate Spider-Man/Avengers comic book, and although I’m currently not buying Marvel products (I’m participating in the Kirby boycott), my kids picked up the Marvel freebie, and I read it. It was fine, in a generic stripped-down, Batman Adventures way.

At the back of the comic was a single-page example of a “Marvel Mash-Up,” where a page from a previously published comic is rewritten with new dialogue that is allegedly funny. Here’s the page I saw:

I’m not offended by the incontinence gags, but they’re nowhere as amusing as Dan Slott’s “Mating Season.” I am surprised, though, that the art is identified as by Steve Ditko instead of Gil Kane. In his Morrison book, Marc Singer argues that the Sheeda—revealed as evolved humans from millions of years in the future, who travel back in time to pillage resources from earlier generations—represent Morrison’s critique of contemporary superhero comics. Like the Sheeda, contemporary comics creators repeatedly strip-mine the rich heritage of ideas inherited from Kirby, Ditko, and other creators, and this “Marvel Mash-Up” shits on the old work too. All I have left are untrustworthy memories and weird associations.