Daniel Clowes on translating his comic from The New York Times to its own book

Pinch Sulzberger’s ad budget and sense of humor permitting, Daniel Clowes could have spent Fall/Winter of 2007 and 2008 being touted by assorted yuppie stereotypes in those annoying “There’s the week, the weekend, and the Weekender” commercials. In arguably his highest-profile comics venue ever, The New York Times Magazine’s “Funny Pages” section, the Eightball creator and Ghost World screenwriter loosed Mister Wonderful on an unsuspecting, and perhaps indifferent, brunch-eating populace. The first in a diptych (with 2010’s Wilson, from Drawn & Quarterly) of stories centered on sclerotic, splenetic middle-aged men, it started out in the witheringly misanthropic vein of Clowes’ previous effort, Eightball #23 (itself about to take book form from D&Q as The Death-Ray), before slowly revealing itself, week after week, to be one of the cartoonist’s most kind-hearted efforts to date. In fact, its story of a divorcé given to obsessive self-censorship and self-deprecation as he takes one last stab at blind-date romance was conceived with the Times’s tony audience, and the “Funny Pages”’ serialized, one-page-per-week parameters, in mind.

Pinch Sulzberger’s ad budget and sense of humor permitting, Daniel Clowes could have spent Fall/Winter of 2007 and 2008 being touted by assorted yuppie stereotypes in those annoying “There’s the week, the weekend, and the Weekender” commercials. In arguably his highest-profile comics venue ever, The New York Times Magazine’s “Funny Pages” section, the Eightball creator and Ghost World screenwriter loosed Mister Wonderful on an unsuspecting, and perhaps indifferent, brunch-eating populace. The first in a diptych (with 2010’s Wilson, from Drawn & Quarterly) of stories centered on sclerotic, splenetic middle-aged men, it started out in the witheringly misanthropic vein of Clowes’ previous effort, Eightball #23 (itself about to take book form from D&Q as The Death-Ray), before slowly revealing itself, week after week, to be one of the cartoonist’s most kind-hearted efforts to date. In fact, its story of a divorcé given to obsessive self-censorship and self-deprecation as he takes one last stab at blind-date romance was conceived with the Times’s tony audience, and the “Funny Pages”’ serialized, one-page-per-week parameters, in mind.

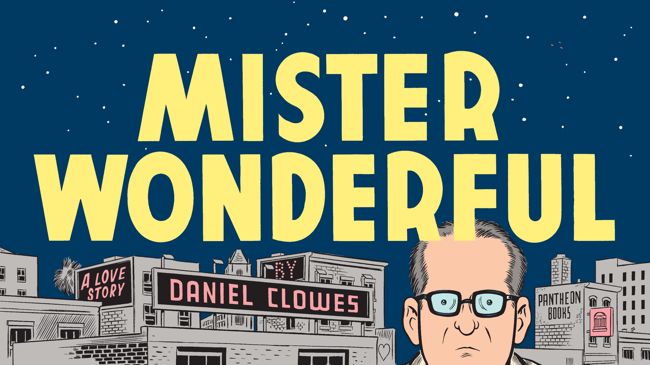

Fittingly, then, Mister Wonderful the book, now available from Pantheon, is a different beast. With its original tabloid-format strips bisected and placed on opposite pages, incorporating occasional art and dialogue tweaks, and interspersed with brand-new material mostly in the form of massive single images stretching across entire spreads, it loses the original’s reliance on punchlines and cliffhangers and becomes a much less dense, occasionally outright spectacular affair. The book’s romantic heart, and that of its protagonist, Marshall, become apparent more quickly, and to more emotionally involving effect. And the renowned cartoonist’s art receives its most expansive, immersive canvas to date.

In this interview, conducted during a late night last week and after a bit of commiseration over our mutual experiences with parenthood, Clowes discusses the creation of Mister Wonderful the strip, Mister Wonderful the book, and how the former became the latter—a process involving David Lynch, Maurice Sendak, Sandra Bullock, and schlubby men in the cafés of Oakland.

This isn’t so much a question as just a “no duh” observation, but the age of the protagonists in your stories has shifted. There were some transitional works, like Ice Haven, which included a mixture—

Ice Haven has every age.

Right. And in The Death-Ray, you depict the same character at different ages. But with Mister Wonderful, and subsequently Wilson, the protagonists are full-fledged grown-up middle-aged men.

Yeah, they’re basically my age. Actually, they’re a little younger than me, which is scary to admit. They’re the age I imagine myself to be, I guess.

Is it just as simple as reflecting where you are in your life?

You know, I can’t really explain it. It’s not something I think about. I don’t set out: “My next book is going to be about a 37-year-old, because I’ve never done that before.” That’s the kind of thing I wish I could think about. [Laughs] I wish I could be that clever, to think in advance of what would be the least likely character for me to do and then do it. These characters just land in your brain and take over, and you can’t really do anything about it. I was on kind of a middle-aged man phase there for a while. I think it started with that Death-Ray story I did; it was mostly about the 18-year-old or 17-year-old version of the character, but then it was framed by the story of the middle-aged version of that Andy character. Originally, that book was going to be half and half, half the old guy and half the young guy, and it just didn’t work narratively. It was too equally weighted on both sides and it didn’t have the right feel as a story. So I cut out the older guy in favor of the younger guy. But I felt that I hadn’t explored that kind of Angry Old Man character enough, and that led to the next two books, I guess. I’d say that Wilson is the last word on that character. I’m sort of done with it for now.

The comparison I’ve made between Mister Wonderful and Wilson is that they remind me of the difference between the Joe Pesci character in GoodFellas and the Joe Pesci characer in Casino.

Ha!

When you meet the Pesci character in GoodFellas, it’s the “What do you mean, I’m funny?” scene, which is hilarious. When you meet the Pesci character in Casino, he stabs a guy in the neck repeatedly with a pen and then kicks him when he’s down on the floor. [Laughter] I always thought that told you a lot about the difference between the two films: Casino was much nastier, almost a rejoinder to GoodFellas making people have so much fun with gangsters. So Wilson was Mister Wonderful weaponized in a similar way.

Ah! I didn’t necessarily think of them as two versions of the same guy. I thought of them like they would be, possibly, friends, or at least two guys who ran into each other at the Post Office in Oakland—sort of the same class. But Wilson is the pure id creature, and Marshall in Mister Wonderful is all superego, all repression. Part of that sprung forth from having to do the strip originally in The New York Times Magazine and feeling this sense that I could not do a character like Wilson. I knew I had to do a character that was very constricted, and what he could do was circumscribed. I decided that instead of letting that be a hindrance, I’d use that as what the story was about. I made him a character that was constricted, and was self-censoring to the nth degree, to where he’s actually obliterating what’s going on around him and living entirely in his own head.

At a certain point when I was working on the strip, the editor called me up and said, “We’ve had a lot of complaints that this character keeps saying the word ‘Jesus,’ so we’re going to have to ask you to stop doing that. You can’t use that word anymore.’ [Collins laughs] At first I was like, ‘That’s an outrage! How can I do that?’ Then I started writing around the world, and I realized that just added more to the story itself. That just made it all the more restricted. He doesn’t even have the words to express his anger. It made it so much stronger that when I did the book version, where of course I was totally uncensored, I wound up leaving it as it was. using all the swear symbols and all the stuff I had in the New York Times out of necessity.

I was going through the Times version and the book version mainly to look for differences in the art, but one dialogue tweak jumped out at me: In the Times, Marshall walks into a darkened room and sees something and says, “Oh, dear God,” but in the book version he just stammers. So your blasphemy count dropped even further in the book version.

Ha! I actually didn’t even think of that when I did that. It was really because “Oh, dear God” seemed like something you’d say in the last panel of a strip when it was gonna be a week before you found up what was gonna happen next. I needed something that wasn’t quite such a final punctuation on the page, that you could turn the page and the scene was still happening. But there you go—I’m sure my unconscious decided, “We must censor out anything that anybody could find offensive!”

How much did the original venue for Mister Wonderful influence the way the story was conceived and the way it was executed? You said earlier that the characters just land in your brain, so which came first, the Times gig, or Mister Wonderful?

It was one of those rare occurrences where…I was working on something else. It was ten in the morning and I was trying to write this longer comic that I was working on for a while that I later abandoned. That was what I was working on that day, and then I got a call at ten, and it was the editor from The New York Times Magazine, just out of the blue, saying “Would you like to do the next ‘Funny Pages’ strip, starting in...” whatever it was, two or three months.

We were talking about the “Funny Pages” section—I had wondered how popular it could possibly be, since nobody I knew was really talking about it. It seemed like all the cartoonists who were in it and the friends of the cartoonists who were in it were talking about it, but it wasn’t the kind of thing that was making the rounds, where everybody was talking about the latest serial fiction piece that was running in there. She said, “Yeah, people are a little confused by it.” She was very careful in the way she spoke, and she said something like, “We’d really love it if you could consider the audience.”

I remember thinking, “Oh, she means, ‘Try to make this one mainstream in a way that will appeal to the New York Times reader.’” Off the top of my head, as a joke, I said, “I should just do a romance story.” I was making a joke—like, a Sandra Bullock movie! A totally formulaic Harlequin-romance kind of a story.

And she laughed, like, “Don’t do that.” [Laughter]

But then, as she was talking during the rest of the phone call, we were going over all this other stuff, I was talking without even listening to what I was saying. I was actually thinking, “That’s a great idea! I could do a romance story!” I immediately thought, “I should try to think of who would be the ultimate, quintessential New York Times Magazine reader—a schlubby, middle-aged guy, the kind of guy I would see reading the New York Times on Sunday morning at a café in Oakland—and make him the hero of this romance.” So by the end of the phone call I had already figured out what I was gonna do. I just bluffed my way through it, saying, “Yeah, I’ll send you some ideas.” Then a week later, I said, “Oh, by the way, remember I joked about that idea?” She liked the idea. That’s what you hope for: Something leaps into your head, and that’s it, you don’t have to worry about it anymore. At 5 pm that day, I’m already drawing pictures of Marshall, and I’m off on that new project. That just never happens.

If you were approached to do the very next one, that had to be one of the shorter periods between the conception of the idea and seeing it in print you ever experienced.

I feel like I got the call when, I think, Megan [Kelso] was ahead of me, and she had just started, she had just done the very first one of hers. So I would have had 20 weeks. I was hardly done with it by the time mine came around—I had done maybe eight of them, or something like that. I had a head start, but by the end, I was turning it in the day before it was due. [Laughs]

I’m glad that you still feel deadline pressure. That makes me feel better about myself, somehow.

I’d never had a deadline in my life for comics, really. I used to turn ‘em in whenever I was done, and then they would solicit it. I didn’t like to think about having to get it out for a certain date for any reason. It just seemed so arbitrary. But this one, I couldn’t miss the deadline. I couldn’t leave ‘em hanging. They had the page reserved! I guess they could have sold an ad for a super-expensive luxury condo or something.

When people say “mainstream comics,” they tend to be referring to superhero comics. I’ve sometimes responded to that by saying, “Really? Superhero movies are mainstream, but in terms of comics, Dan Clowes was in The New York Times. That’s a mainstream comic.” Is that something you felt as you were doing the strip?

That was part of the fun for me. I’d always wanted to try to write something for an audience. I don’t really like to think about who’s reading when I’m doing my own stuff. I have this vague sense of someone who’s sort of an alternative version of myself reading my comics. In this one, I wasn’t necessarily tailoring the jokes or the situations for a certain reader, but I was trying to make it clear for someone who had no knowledge of comics, didn’t understand all the fancy devices of modern comics. Somebody like my parents or some neighbor who’s not that interested in comics at all—I tried to imagine what they might actually read. I can’t say that I was necessarily successful. [Laughs] People used to say to me after that strip was running, “Boy, you must be getting so much attention for this, and getting such a response!” I remember that the year the strip was running, I actually got more response for the Christmas card I sent out than for the entire run of that strip. [Laughs] It was really a weird vacuum. I got the idea people were reading it, but there was no mechanism to respond to it. They didn’t have comments on the New York Times site where they were running the pages, and they didn’t run letters in the magazine. They would send me e-mail responses every once in a while, but they were always these little old ladies from Virginia, people who would write [in a little old lady from Virginia voice], “My mother’s name was Nathalie, so it’s great to see someone with that name!” It was a very strange experience. I talked to all the other artists who did the strip, and they all said the same thing: It was a ghost-town of response.

In comics, anything that appears outside of the usual venues almost doesn’t seem to exist. Alvin Buenaventura has been editing a comics section in The Believer for god knows how long, and I’ve never heard anyone talk about it.

That’s true. It’s amazing! Every month! [Laughs] That’s true. I see Alvin every other day, and I completely forgot he was doing that until he said something about it the other day. I was like, “Oh my God, I haven’t looked at that in three months!”

There’s something [else], too. We all had the delusional fantasy that a modern audience could actually read a continued weekly strip. That was certainly true back in 1940—people could follow the Sunday continuity of Terry and the Pirates, and sit around on Thursday chomping at the bit to see what was gonna happen when he fell off the cliff last week. That does not exist anymore. The audience does not have that kind of attention span. By the time the next week came around, they’d just be like, “Oh, yeah, this thing.” They hadn’t thought about it at all. I can say that that was true for me with all the other strips that ran in there. I read them very sporadically, and sort of forced myself to read them. I cut them all out, and eventually I’d sit down and read the whole continuity of each one in order, and it would work really well. But it doesn’t work in the modern world, to have a continued thing like that. They should have had something more where it was a different guy doing a single-page strip every week. I think that might have worked better. If they gave people three or four pages, that would have been the greatest, but they would never do that.

That’s quite an investment of real estate in any one issue.

Yeah, no, you can’t take that risk. You’d have to copy edit it and go over it and make sure it was worth the pages, and it would be such a pain in the ass that it wouldn’t be worth it.