Mister Blueberry 29: Dust, by Jean Giraud. Dargaud, 2005.

Arzak L'Arpenteur, by Moebius. Glenat/Moebius Production, 2010.

Inside Moebius Tome 6, by Jean Giraud Moebius. Stardom Editions/Moebius Production, 2010.

The work of Moebius is so under-represented in the English language that it hardly bears mentioning. Everyone who has seen one of his drawings wants to read a book; everyone under 40 can tell the same story of comic store frustration at the discovery that he lacks a robust in-print catalog. For decades he didn't have one at all! It's an obvious bummer that few in the English-speaking world have been able to read The Long Tomorrow or Arzach for 30 years. But just as unfortunate, I think, is that the understandable hunger for the stone cold classics of the '70s and '80s has almost totally obscured popular consciousness of Moebius's late-career works.

Great cartoonists get weirder as they get older; as a general rule they stop expanding the scope of their work and drill down into old obsessions, attempting to answer the few fundamental questions that hindsight makes obvious they've been asking all along. Like Herriman or Ditko or Alan Moore, Moebius became more idiosyncratic and introspective with age, often seemingly in search only of himself. The final installments of three series that he spent significant chunks of his career working on - Arzak, Blueberry, and the newly translated Inside Moebius - provide compelling insight into where their author stood as he faced his end, and a look back at everything he'd picked up along the way.

The Blueberry volume is the weakest of these selections, which perhaps is no surprise. Moebius's civilian identity as mainstream six-gun opera illustrator Jean Giraud always seemed to lack something. If you're into Moebius you're down to get a little weird, and Blueberry plays it straight. Especially in the earlier volumes (the only ones we've had in English), the influence of Milton Caniff and the "house style" of French Westerns pioneered by Jije always seems a little too close at hand. By the time he drew Dust in 2004, however, Giraud was content to be himself. The drawings are unmistakably his... but this still isn't what most people look for from a Moebius comic. Moebius had one of the most formidable design senses ever seen in comics, birthing an entire visual lexicon that's spread from comics into movies, video games, and increasingly, the gallery arts. In the Western series that kickstarted his career and acted as a constant shadow of his better known sci-fi work, Moebius the visionary is tied down and Giraud the pure draftsman pulls the weight.

Fortunately, that guy isn't exactly a slouch. The combined talent Moebius brought as designer and draftsman is close to unprecedented in comics; you'll have plenty of fingers left over counting the cartoonists who equal it. Reading books like The Incal or The Airtight Garage can be overwhelming: you have to go slow and put them down a lot because there's just too much input on the pages to deal with all at once. Seeing Giraud the pure draftsman knock out a straightforward Western using all his excess energy on staging and basically none on design might be a lesser pleasure, but sometimes you just want a sandwich and a Coke, you know? Here ya go!

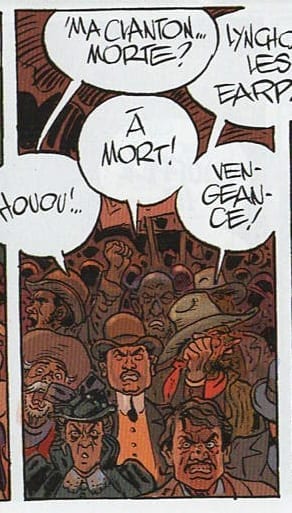

The never-translated late-period Blueberry books are basic genre executed with a level of visual mastery that most comics can only dream about. Every character that appears on the page, no matter how minor, is a uniquely developed individual cartoon; every location is imagined as vividly as if its artist were right there drawing it from life. One gets the sense that Blueberry's world expands out and out to form an entire continent inside Giraud's mind - that he can just zoom in on whatever particular region or population is necessary and draw it in an instant if need be. (This volume covers quite a bit of that imagined territory, moving from parched desert through deciduous forest into a snowbanked climax.) The panels above are all little ones, tossed off to fill space on the pages during the expository scenes that link the big set pieces - the one of all the guys yelling is literally printed at the size of a postage stamp. But look at 'em, man! The concreteness not just of the facial expressions, but the facial features. The deadpan ease with which a few marks perfectly capture the texture of piñon bark. The way the figures seem stapled to the ground by gravity, yet alive with the force of their movements. The mastery of perspective. Dust opens with a propulsive multi-stage action sequence that provides more meat than anything else in the book, but really you'd stop and gape at any of these drawings if they appeared in most comics.

The never-translated late-period Blueberry books are basic genre executed with a level of visual mastery that most comics can only dream about. Every character that appears on the page, no matter how minor, is a uniquely developed individual cartoon; every location is imagined as vividly as if its artist were right there drawing it from life. One gets the sense that Blueberry's world expands out and out to form an entire continent inside Giraud's mind - that he can just zoom in on whatever particular region or population is necessary and draw it in an instant if need be. (This volume covers quite a bit of that imagined territory, moving from parched desert through deciduous forest into a snowbanked climax.) The panels above are all little ones, tossed off to fill space on the pages during the expository scenes that link the big set pieces - the one of all the guys yelling is literally printed at the size of a postage stamp. But look at 'em, man! The concreteness not just of the facial expressions, but the facial features. The deadpan ease with which a few marks perfectly capture the texture of piñon bark. The way the figures seem stapled to the ground by gravity, yet alive with the force of their movements. The mastery of perspective. Dust opens with a propulsive multi-stage action sequence that provides more meat than anything else in the book, but really you'd stop and gape at any of these drawings if they appeared in most comics.

Seeing it all drawn with a brush is another simple pleasure. Again and again the crashing chaos of panels with far too many marks, lineweights far too variable, is reined into order by an unerring sense of light, space, and depth. The weightless line of a rapidograph might have given Moebius his cold futurism, but Giraud's way with the brush is just as technically impressive. The panoramic shots stand out, giving us peeks at landscapes with more character to them than the figure drawings in an average Western have. It's all set down with a sense of ease, Giraud's neat flicks of the brush growing finer as they retreat along the lines of perspective, grounding everything in an incredibly concrete mise en scene. This is a different function of the same design sense that built Jerry Cornelius's hermetic garage: at its core is visionary potential, the ability to make things imagined seem real. It's nice to be reminded of just how talented this guy was with an unassuming exhibition of his less-discussed skills that still blows most comics makers' career highs out of the water.

The knee-jerk assumption that Dust was commercial work divorced from its visionary artist's passions isn't necessarily accurate. Though the cover bears the name of Blueberry's cocreator, writer Jean-Michel Charlier, Giraud scripted the final five Blueberry books alone following his collaborator's passing in 1989. Inertia didn't pull Giraud into this book, much as the fact that it's the 29th volume of a series might seem to imply such. Putting on this kind of virtuoso pure-drawing display, as well as flying solo across the terrain of his longest-running character's adventures, must have mattered to him. He wouldn't have done it otherwise.

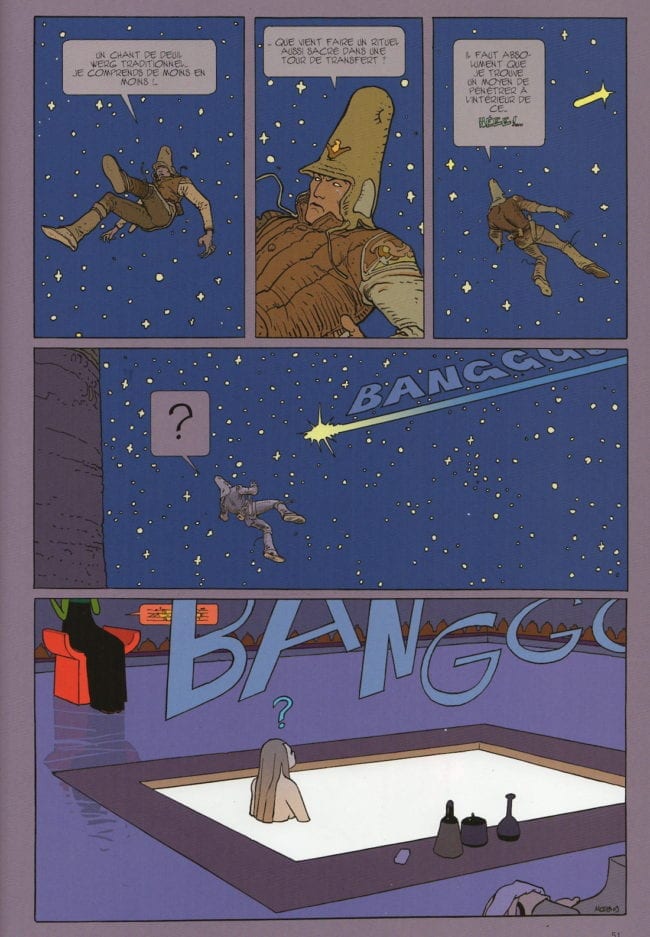

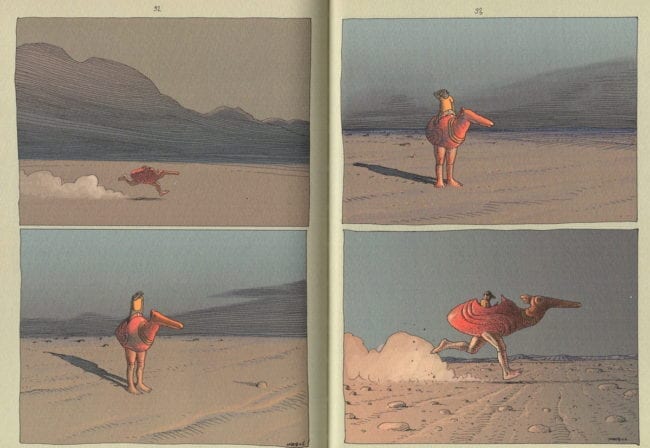

A look at Arzak L'Arpenteur, the last dance of Moebius's iconic pterodactyl-riding, tall-hatted adventurer, gives a hint as to why a final exhibition of skill and saleability might have been important to him. Drawn a few years later in 2008-9, its visuals carry an unexpected simplicity, bordering on crudity, that perhaps was born of necessity. I've read that toward the end of his life Moebius had good days and bad days at the drawing table, and that digital tools became more and more a part of his process as he was forced to stitch together workable compositions from different drawings' component parts. Miles from the hyper-intricate, starkly designed visual style of the iconic original Arzach strips, this Arzak (with a K) is a reverse image of the look at Moebius that Dust gives. The book contains a welter of far-out visuals while providing a primer on the foundations underlying its creator's talent. The pin-thin line of Moebius's classic '70-'80s period is long gone from L'Arpenteur, replaced by thick, scratched trails that make up in expressiveness what they've lost in delicacy. Those whose familiarity with Moebius begins and ends with the meticulous vistas of his Metal Hurlant days will almost certainly see his latter-day embrace of a minimal style as evidence of decline, but open space was always a defining trait of his drawing. His explorations of a simpler ligne claire-derived idiom date back just as far as his more florid work, but expanded the older he got.

The computer is very much in evidence here, its voice autotuning its creator's imagery into a place as different from "classic Moebius" as it is inextricable. The most noticeable change can be seen in the colors. I think the sublime flatting combinations Moebius assembled in his prime are at least as big a contributing factor to his enduring popularity as his rendering style itself. Without them, he's a talented psychedelicist with technical chops and a Crumb influence. With them, he was something else, something bright and glowing you always sensed should exist but no one else was able to show you. (Should you require more proof of the contribution color made to Moebius's career highs, and possess a strong stomach, check out the absolutely hideous recolored version of The Incal that DC put out in the early 2000s.) Moebius's hand-coloring approach (often in concert with the work of assistants) was never too complicated: establishing a striking color as a ground, he would build up shape and depth with darker and lighter values of the same tone before marking out the essential information a picture contained with a strong contrasting hue, usually combined with areas of white or black. In a modification of this approach, he would form a ground with pastel tones before using a bold color for pop.

In L'Arpenteur, the computer changes everything. Like David Hockey on his iPad, Moebius seems to have found the possibilities provided by digital color dizzying. I've always found it odd that Moebius was such a relatively shitty painter, given his skill set, but he was a graphic artist first and foremost; blending elements together into a perfectly unbroken pictorial ground didn't appeal to him as much as popping things out at you, making them separate. On these pages digital brushes streak garish highlights and lowlights into surfaces without being overly subtle about it. It's the subtle color choices that let this approach work at all; boldly slashed across the panels, the rendering lines function as compelling markmaking in and of themselves. They look like alien graffiti tags if you focus on them, and fade into the picture plane quietly adding dimension to the forms if you don't. The colors used are a departure as well; instead of pinballing between thin slivers of the color wheel, L'Arpenteur's panels hammer down tent stakes across wide wedges of it. Rhyming tones distinguish background details as subtly as possible, and contrasts between the dominant elements of panels set them off from each other, rather than just pushing them out from the ground. A few panels ditch drawn backgrounds completely for flat color fields, using forced perspective alone to indicate depth. If you've ever wanted a Moebius comic that looks like a riff on Tim Hensley, here it is. The choice to color the gutters between panels in shifting hues that quietly complement each scene's unique color identity also pays great dividends.

The simplified drawing approach refocuses the reader's attention from drafting to blocking and panel transitions. That head-chop page above is bracing, as close to Kirby-impactful as Moebius got, but there are quieter moments whose construction stands out too. A sequence of our hero being stalked by an ever expanding pack of strange black catlike creatures as night falls is a standout, as is a sexually charged passage in a lavish tower-top apartment that shows crazy sci-fi worlds weren't the only thing Moebius could design from the ground up. The plainspoken drawing brings the power of the pictures' subject matter into focus as meat for color compositions and exercises in visual imagination. Landscapes resemble emerald elephant graveyards, beds of pastel flowers bloom like coral forests, and a menagerie of alien creatures ambles by, each one stranger than the last. Occasionally the panels edge over into total abstraction, offering a glimpse of the master's image-making power untethered from any need to make sense.

The drive for simplicity and focus on design extends to the actual pictorial solutions. The cold depths of outer space, rendered with such painstaking dimensionality in early Moebius, become a background tapestry of white circles on pure blue, unexpectedly echoing Winsor McCay. A scene of our wandering hero treed by a monster, recalling one of the first Arzach stories, foregrounds a creature that could easily have sprung from Gary Larson's pen. A nude woman slowly lowers herself into a shining pool of blank white space. The clothed areas of characters' bodies are rendered as brightly colored silhouettes. Moebius delivers plenty of his old razzle dazzle too - the scenes among towering rock formations are full of fluid hatching that's as specific to its creator as can be - but the most evocative images in this book are the ones that look the least like the stuff that made their artist famous.

Interestingly, Arzak L'Arpenteur's story - or the half of it that features the titular hero, at least - ends up treading into territory reserved for one of the other guys who made Moebius famous, a certain Mr. Blueberry. While a cosmic battle between humanity and the alien Wergs paints the heavens, Arzak wanders through a very Western-y outpost on the trail of an operation trading in the extraterrestrials' heads. It's given an appropriately sci-fi cast by the design choices and the inclusion of some bizarre side characters, but it feels like the map of Moebius's internal landscape folded down and in on itself as he approached his end, turning in ever narrowing circles to reach the single creative spark that powered so many different things.

That process is concluded in Inside Moebius 6, credited to "Jean Giraud Moebius", an integrated identity that covers the sum total of its bearer's creativity. Inside Moebius is a truly bizarre metafictional series that sees the image of artist himself interacting with his fictional creations, using them as a kind of psychiatrist's couch amid the expanses of Desert B, an arid landscape much like those seen in both books discussed above. The first volumes of Inside Moebius are little more than sketchbook comics documenting a master practitioner's playful examination of his own creativity. By the series' final installment it had become much more: volume 6, drawn between 2004 and 2009, feels distinctly like its creator's attempt to grapple with old age, infirmity, and approaching oblivion.

The casual fluidity of line seen in vintage Moebius that becomes a scrawl in Arzak L'Arpenteur has degenerated to a scribble as this book begins. The computer colors, too, are downright ashen. Dust grays and sand browns fill the pages, the brightest thing in sight the pale orange shirt worn by Moebius's cartoon avatar. The cartooning is as loose and bigfoot as Moebius ever got, with rounded forms seeming to billow in the desert wind. The lettering approaches illegibility. Rare is the page with more than three panels on it. The comic seems to be struggling to pull itself together into something that actually exists.

Slowly, it does. The thin-lined grace of vintage Moebius appears in glimpses, like light shining through cracks in an edifice, before breaking free entirely at the book's midpoint. It's welded to the simplified forms of the early parts of the book, and the dense hatching that once dominated the artist's pages appears sparingly, adding wisps of texture to figures fixed against stark, harsh backgrounds. Splashes of brilliant color creep in as well, hazy violets and mottled greens with substance beaten into them by speckles of digital texturing. Bit by bit, they immerse the ashen world we observe. The effect of this book's transformation from slashed-out basic cartoons to glowing, elegant memento mori is reminiscent of William Basinski's classic The Disintegration Loops: both a journey and a meditation on ruin.

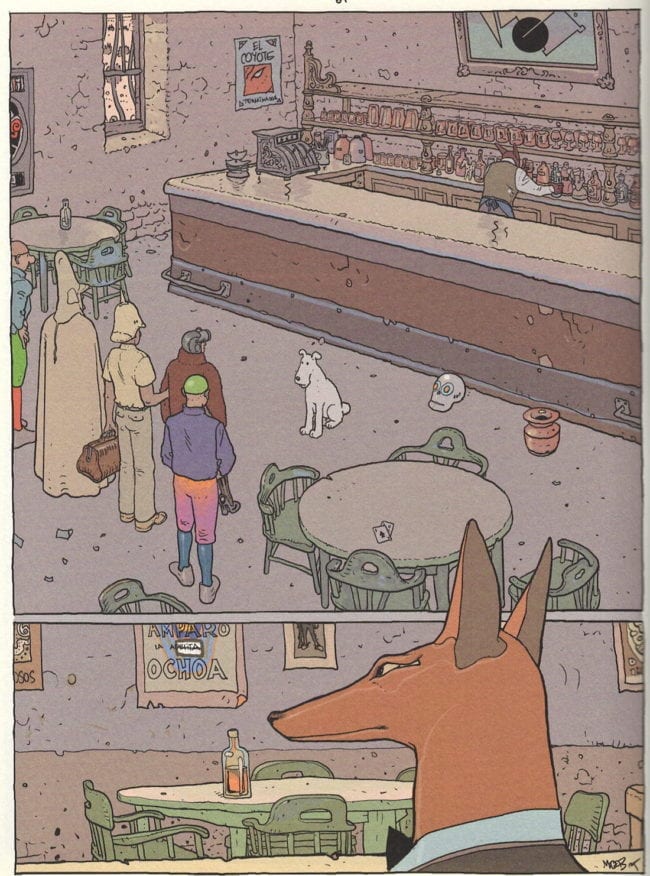

Unlike plenty of greats across the spectrum of artistic endeavor, Moebius doesn't let the shadow of the end dampen his work's energy or blacken its outlook. (The act of smoking weed has never received as heroic a visual treatment as Moebius gives it here.) Visual punchlines and the author's eagerness to lampoon himself are everywhere in this book, which is at root a funhouse ride through a world artist and readers know well, with a group of old friends alongside. But it can't help feeling like a funeral too. The book's cast of classic Moebius characters, drawn in a style somewhere between the bold simplicity of L'Arpenteur and their original forms, feel like the shades of themselves, flickering across the surface of the pages as their author's creative life flashes before his eyes at the drawing table. Does anything define delirium better than talking to people who aren't real? Perhaps only a man conversing with fictional characters of his own creation.

Death imagery abounds in Inside Moebius 6. A tiny green skeleton grabs onto the author's leg as he gets out of bed to open the book; skulls populate the panel backgrounds. The aged Moebius encounters a much younger, more vital version of himself who joyfully if buffoonishly avoids all the pitfalls that buffet his elder, wizened, through the pages. The action we follow is repeatedly revealed as an illusion: a theatrical performance, a Shining-esque miniature maze, a series of drawings. The plot sees a coyote ("The" coyote, one character insists), a ringer for the Egyptian death god Anubis, tracking the author across the wastes of Desert B before a final meeting.

This encounter triggers a towering suite of narrative-free psychedelic imagery, which sees Moebius's body transformed into a whirl of abstract shapes, wandering through a series of hallucinatory vistas, entombed in a futuristic sarcophagus, the subject of ruined statuary, with skin pulled tight to reveal the contours of the skull beneath. Then it ends, and the younger Moebius ambles into the book's last few frames to discover the death mask of his aged self in the sands of Desert B. He picks it up, stares, then looks out of the panel at us in perplexity. In a final splash page he walks away, whistling and smoking a joint the size of his forearm.

If any of Moebius's works earn the adjective "hermetic", it's not the one that used it in the title, but this book: an exploration in the land of the dead. Numerous are the Moebius comics that explore aspects of spirituality, usually from Gnostic or New Age angles emphasizing identity and vitality, the life force and changes in physical form. The living spirit, in short. This one peeks onto the other side, simply and directly, without fear. The artist's insistence on foregrounding his own image in the final sequence is highly telling. This is who I am, who I was, how I want to be remembered, he seems to say with pride. One picture is particularly indicative: a naturalistically rendered Moebius stands in a phantasmagoric landscape. The top of his head has been removed and intricate keys shaped like hands, tusks, coyotes spill out from his cranium. Enigmatic behind opaque glasses, he holds one out to the reader, smiling.