Let's take a look at ten of the most interesting comics that have come my way over the past few months.

Snake Oil #7, by Chuck Forsman (Retrofit)

Forsman tells yet another story about teens, this time a love triangle involving a terrible high school band called Witchzard. Forsman is great at evoking the ways in which people try to pretend that they're not in pain, matching it up with a loose drawing style that brings to mind Charles Schulz. Each of the main characters--John, the lead singer and guitarist; JC, the drummer; and Jess, the bass player who's the object of affection for both boys in the band--is unable to directly express his or her emotions, frequently in hilarious ways. As we learn in surprisingly poignant and subtle fashion as the story proceeds, John is acting out because of the death of his older brother, who was his idol. JC is jealous of John and Jess is ambivalent because she'd feel guilty hooking up with either one, leading to a climactic fight at the end of the story that of course resolves nothing.

The fact that all of this drama is under the aegis of kids trying to live out their rock 'n roll dreams makes it all the funnier and more ridiculous, as John gets the idea to eat his sister's gerbil onstage after a demon induced by a glue-huffing sessions tells him to do so. Of course, in this story, even most of the dream sequences have a depressingly mundane quality, like when John "meets" his brother after being punched out by JC. Told that he's in heaven, John retorts with the ultimate teenager putdown: "Heaven is stupid." This is a genuinely pleasurable comic book, from the format to the character design (John's little sister has a mouth that curls up in anger just like Sally Brown) to the effects (lots of zip-a-tone) to the slightly removed narrative style. Forsman gets all of the details right, and in this sort of story, the details are everything.

Pansy Boy #2, by Jose-Luis Olivares

This comic is part of Olivares' continuing subscription service, wherein he sends out monthly minicomics, art, and other ephemera, and is the second installment of a series that meditates on gender identity and sexuality from the viewpoint of a child. This is a jarring read, transitioning from a child's wish to fly as he is zipping back and forth on a swing to a sweet moment with a friend to an ugly session of playground sexual politics. The cover, decorated at the bottom with crayon (the crayon wrapper is included with the issue--a nice touch) features that innocent bit of whimsy, then transitions into the young boy being asked to get married by a little girl. The girl saying "Are ya hurt?" when the boy flies off the swing is actually quite sweet in its own way. Then comes the gang, who essentially hold the girl down and tell the boy he has to kiss her in a moment that is uncomfortably close to sexual assault. The peer pressure is too much for him, so he does it, only to be slapped hard by his former friend, amidst the laughter of the other kids. It's a brutal moment made all the more difficult by Olivares' childlike but highly effective scrawl of a line. As he continues to work in tighter narrative forms, Olivares' talent is really starting to shine.

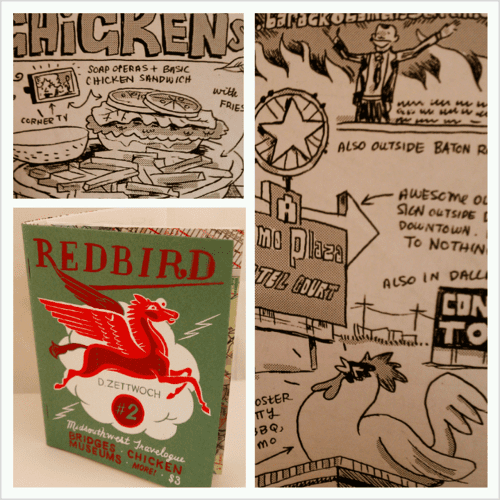

Redbird #2, by Dan Zettwoch

In terms of both form and content, Zettwoch is perhaps my favorite minicomics artist of all time. I am in awe of the sheer craftsmanship he pours into each of his creations; it's a reflection of his mix of a punk/DIY aesthetic and an artisan's work ethic. This issue of his catch-all minicomic series details a road trip he took around the country with his wife. Because it's Zettwoch, this means a breakdown of various sights and attractions into list/diagram form, all spun with a folksy wit and charm. The endpapers for the comic are cut from an atlas. There's a crazy double fold-out in the middle of the comic. When you fold the flaps out and extend them, you get to read about the top five fried chicken experiences Zettwoch had on the road. When you unfold those pages up, you get the overarching map of everywhere Zettwoch and his wife traveled.

Along the way, Zettwoch also reveals the top five bridges he traveled across, selected signs of the "midsouthwest," the three best roller rink realms, the top five museums, and the top three bands they saw. The front and back covers are gorgeously screen-printed from images actually seen on the road, be they from an oil sign or a work of fine art. This is fitting for Zettwoch; he sometimes conceals his keen mind and eye for detail in his affection for detritus, kitsch and otherwise disposable culture. He's equally adept at succinctly discussing his interest in both high and low culture, as his accounts of what struck his eye in his museum travels attest. Zettwoch is fascinated by America and all of its contradictions; his book Birdseye Bristoe explores this in detail, especially in terms of local culture vs encroaching, corporate culture. This issue of Redbird is just another segment of his career-long love affair with documenting and celebrating the odd, the offbeat, and the provincial.

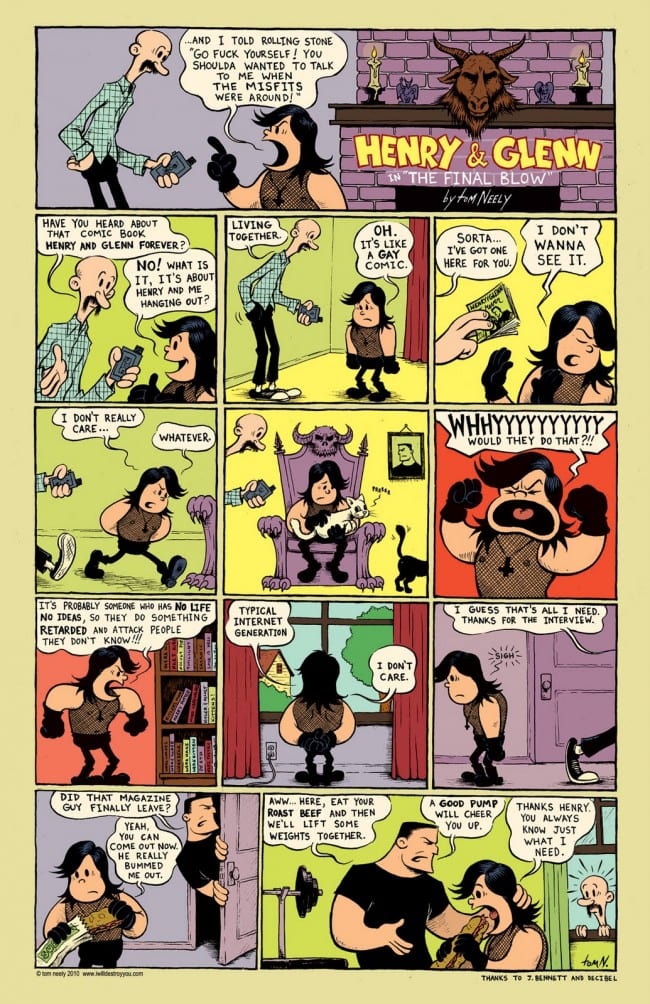

Henry & Glenn Forever & Ever #1, by Tom Neely, Ed Luce, Benjamin Marra, & Scott Nobles.

This is the latest and best installment in the Neely-instigated concept imagining fictional versions of macho rockers Henry Rollins and Glenn Danzig living together as lovers, a gag that's taken on a life of its own. This new comic, presumably the first in a series, is a slightly more conventional take from the original source material. The result is the funniest comic I read in 2012. Neely formats the comic like a classic EC horror book, complete with a Crypt-Keeper torturer sort of character who informs the reader what sort of torture each of the book's artists is suffering as a result of their "degenerate art."

That's a nice segue point for each of the different approaches in the book. Neely's rubbery, cartoony "Buried Secrets" combines elements of E.C. Segar, Chester Gould, and Archie comics into a story that portrays Danzig as a hysterical drama queen (which is not all that far off from the truth). It's just that Danzig in this story is now writing songs about pizza rolls and taco Tuesday ("You just don't get me! I'm evolving as an artist!") and putting on Raisin Rampage nail polish. In the hands of Benjamin Marra, a camping trip designed to mend Henry & Glenn's relationship turns into a battle with a sect of satanists led by '80s rocker Lita Ford. As one might expect, Satan himself rises from the earth at the end of the story.

My favorite story was Ed Luce's "Henry and Glenn For Five More Minutes", which involves the couple in a therapist's office, trying to work things out. What made this strip so fun was Luce's shots at the most ridiculous moments of both men, like Henry making fun of Danzig's "demon boobie comics" (which are truly atrocious). The story reaches its comedic peak when the therapist suggests them seeing other people (for Glenn, Kerry King of Slayer, performing animal sacrifice; for Henry, Ian MacKaye of Fugazi, knitting "This is not a Fugazi scarf" by a fireplace). Sure, some of these are music fandom in-jokes, but so what? Luce lands direct hit after direct hit in a manner that's still funny even if one doesn't understand every reference. His naturalism in some ways is even more cartoony than Neely's story, given the larger-than-life qualities of the protagonists. The pin-ups and gags at the end of the book add extra flavor, especially Coop's depiction of Danzig riding Rollins like a horse. This is the sort of comic where the concept will sell you on reading it or skipping it; the good news is that it lives up to its idea.

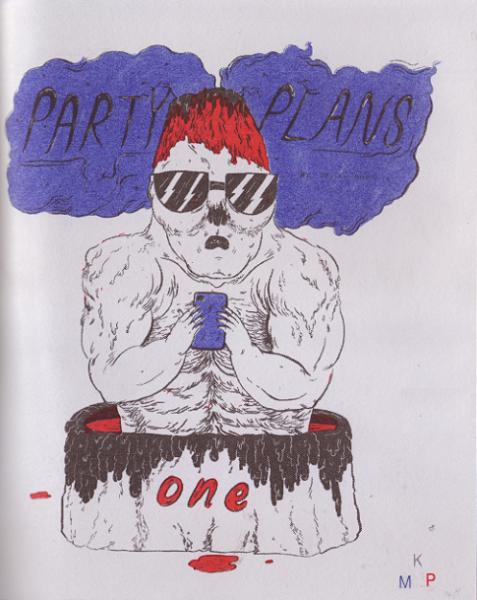

Party Plans #1, Upset Cats, Let's Do It by Zejian Shen.

Shen is part of the Collective Stench group, a collective I was entirely unaware of until her comics showed up in my mailbox. To say that her style of drawing and sense of humor line up precisely with the sort of comics I like is an understatement. Each one of these comics is a sheer delight, reminiscent of two of my favorite cartoonists: Chris Cilla and Matthew Thurber. There's a touch of the grotesque and bizarre in her work, but she also mines the same kind of Dada absurdity that informs Thurber's comics so hilariously, as well as his surprisingly iron-clad command over both plot and character.

Upset Cats and Let's Do It are short, one-joke comics. The former is exactly what it sounds like: drawings of cats dramatically expressing their woes, with captions ranging from "a mystery" to "I hate peanuts" to (hilariously) "TETSUO!" The latter title initially seems to be about having sex in any number of locations, but as the comic is folded out, it turns out to be something far more grisly. Shen has a nasty streak in her work that pops up in unexpected ways at surprising times, and this is a good example of that tendency.

The first issue of Party Plans involves an increasingly complex web of characters interacting with each other in what begins as a fairly simple set-up: the powerful character Victor Volcano is planning a party for his girlfriend Betty Boulder. That is, until he receives a text and photo from an unknown source that shows Betty in a compromising position with another man. From there, we are introduced to V.V.'s right-hand men (Bobby Basilisk and Damien Desertt), his estranged best friend hurtling through space, as well as assorted assassinations, machinations, betrayals, discoveries, and sleuthing. Shen's anthropomorphic geological features and animals are impeccably and humorously drawn and often take the reader down odd but straight-faced detours. At the same time, the book works as both a celebration and satire of pulp and soap operas. She also utilizes the animal nature of some of the characters quite cleverly, like when the detective Montgomery Mongoose hunts down Bobby Basilisk. There's a static quality to her pages that I find interesting; new characters are introduced with a half-page spread on the left side of the page, almost modelling for the reader as they're introduced. Her panels don't depict motion so much as they depict character poses, which heightens the melodramatic and funny nature of the comic while otherwise playing it straight. Zejian Shen is certainly one of the brightest new comedic talents in comics, a fully formed cartoonist whose chops are excellent and who possesses an intuitive grasp of where she wants to go in terms of narrative.

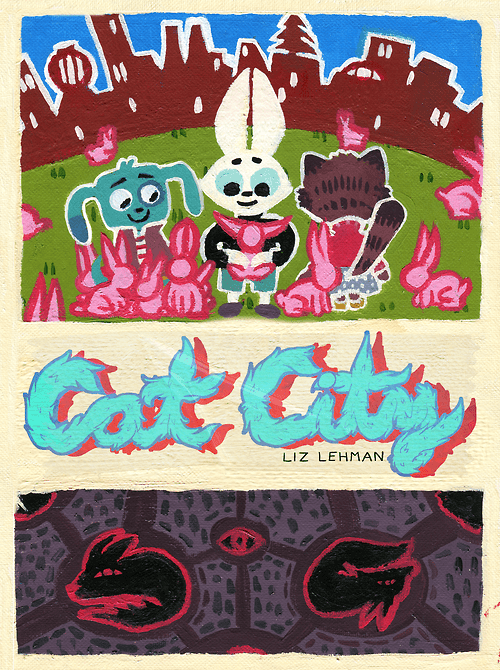

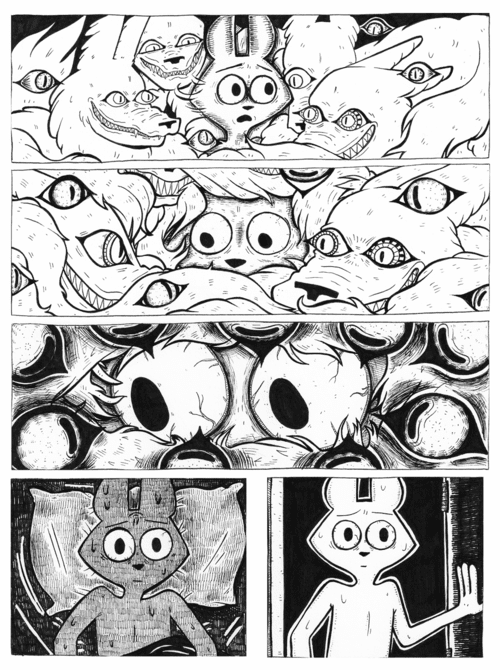

Cat City, by Liz Lehman

Micropublishers are truly popping up like mushrooms these days. This is the first publication by Kyle Petersen of Rigged Books, from a theater student who is just getting into comics. This is her first real work, and it's an audacious and confident debut. It helps that Lehman is a skilled draftsman who's obviously thought a lot about narrative, because her trio of leading characters are fully-formed and distinctive. This is a book about transformation, evolution, and the fears that can spring up around both. Lehman's use of funny animal figures for her characters is not just a quirk--it's essential in the way she depicts people trying to be something they're not, as well as seeming to be something they're not. The three principles are a pair of roommates (Denver & Milo) and their waitress friend Lil. There's a kind of Dan Clowes quality to the nature of their relationship, one that's somewhere between symbiotic and parasitic. That's a dynamic that changes as the story proceeds and the reader is let in on some backstory.

Each of the three characters has their own drama. Milo (a dog) is crestfallen that the college professor he had been seeing not only unceremoniously dumped him, but also essentially denied his existence. Denver (a dog who looks like a rabbit but is part wolf) is a drunk whose life is given meaning by helping Milo. Lil (a cat with raccoon eyes) is escaping her past and her inability to grow and evolve. Her friendship with Denver and Milo is such that she likes seeing them as a mope and a drunk, respectively, because she feels that if they put themselves together that they'd have no use for her. The funny animal conceit allows Lehman to delve into some nightmarish imagery, such as spectral bunnies who lead Milo to the brink of death and the wolves who haunt Denver's dreams. In the end, Milo makes it through and reaffirms his friendship with Denver, but Lil leaves after she sleeps with Denver. Intimacy is a warning sign for this character who never wants to see her true face exposed, something that's emphasized by the front cover (she's facing away from the reader) and the back cover (there are sculptures of each of the characters staring into a mirror, and Lil's face is obscured by a furious scribble). There's a little bit of over-rendering here and there in this densely hatched and cross-hatched comic, but for the most part it's an impressive and promising debut for an interesting new voice.

Smoo Comics #6, by Simon Moreton

Moreton's quiet, poetic comics have evolved to the point where he's eliminated all unnecessary lines. Moreton's very much in the John Porcellino wing of the comics-as-poetry school as he tells very short stories about his environment, his memories, and his anxieties. The quality of Moreton's line is different from Porcellino's, as his style is more explicitly about the lines we don't see than Porcellino's more specifically simple rendering. With Moreton, we see just a few curves of a car, a few lines of a brick wall, a few intersecting lines that represent a street. Indeed, one can feel the influence of Warren Craghead at work here, yet Moreton's voice is more direct.

In "One Day", Moreton's character is walking around, imagining that he's hearing a Hüsker Dü song coming from every window, depicted as blank word balloons. In "Summer", Moreton makes extensive use of grey in order to outline a rainstorm and the subsequent accumulation and evaporation of water. It's just one beautiful beat after another, as the artist tries to capture not just the appearance but the aesthetic experience this day invoked. "Houses/Homes" mixes the geometric reduction of the first story with carefully applied pencil shading to evoke the evolution of a space from an alien environment to home; the last image, of a steaming mug of tea, really brings this point home. "Do You Remember" and "Routines" are further variations on these ideas, with the former standing out thanks to the narrator visiting Stonehenge, as its shaded shapes dominate the page; and the latter an especially abstracted depiction of navigating a crowd and an environment and the moods & emotions they create. Indeed, Moreton's work can be reduced to that very statement: how he reduces the environments, memories, and people he interacts with down to their essence. It's not detachment, but rather a push and pull with full engagement, as complex emotions or feelings can be plainly spelled out as the reader stretches them over the bare bones of illustration he provides. The more confident Moreton gets, the bolder he is in leaving more detail out of his drawings.

In "One Day", Moreton's character is walking around, imagining that he's hearing a Hüsker Dü song coming from every window, depicted as blank word balloons. In "Summer", Moreton makes extensive use of grey in order to outline a rainstorm and the subsequent accumulation and evaporation of water. It's just one beautiful beat after another, as the artist tries to capture not just the appearance but the aesthetic experience this day invoked. "Houses/Homes" mixes the geometric reduction of the first story with carefully applied pencil shading to evoke the evolution of a space from an alien environment to home; the last image, of a steaming mug of tea, really brings this point home. "Do You Remember" and "Routines" are further variations on these ideas, with the former standing out thanks to the narrator visiting Stonehenge, as its shaded shapes dominate the page; and the latter an especially abstracted depiction of navigating a crowd and an environment and the moods & emotions they create. Indeed, Moreton's work can be reduced to that very statement: how he reduces the environments, memories, and people he interacts with down to their essence. It's not detachment, but rather a push and pull with full engagement, as complex emotions or feelings can be plainly spelled out as the reader stretches them over the bare bones of illustration he provides. The more confident Moreton gets, the bolder he is in leaving more detail out of his drawings.

Ci Vediamo, by Hazel Newlevant

Meaning "I'll see you" in Italian, this Xeric-winning comic is essentially one long, well-executed formal gimmick. At just 24 pages, it doesn't wear out its welcome. It's a wordless meditation on lost love, setting up a page of images and then changing the meaning of those images by flipping a vellum page overlay onto it. An empty street turns into one with an old lover on it. A figure looking off into space as she's leaning up against a wall turns into one where she's staring at her lover's shadow. Silhouettes turn into figures, and figures turn into silhouettes. Two flowers transform into two people kissing. It's a slight idea, but the novelty of the form and the skill in putting it together make this a worthy read. It's a comic that's constructed as much as it is read, and Newlevant's formal tricks really do contribute to the comic's downbeat and meditative atmosphere, along with the evocation of autumn as the representation of loss. This is a promising debut.

Annotated #9, by Aaron Cockle

None of the stories that Cockle writes seem to be directly connected, yet there's an implied continuity in his ongoing, abbreviated descriptions and anecdotes concerning bureaucracies, conspiracies, mysteries and the unexplained. "Notes From the Source" involves a conversation between two people (agents? ex-agents?) having a conversation and then going to the man's apartment to have sex. This sex was for a specific purpose: to access a sort of Philip K. Dick-like intelligence in the form of a ball of energy. Here, the crude sketchiness of Cockle's art serves the story perfectly, as this being couldn't really be captured in a slick or naturalistic style. Cockle seems to be following scraps of information as a kind of road map to enlightenment, creating a path for readers at the same time as he's mocking his own process (one character refers to certain comics about "their horrible lives filtered through bizarre science-fantasy amalgams").

The second story, "Exit Interview", feels akin to the sort of thing that Tom Kaczynski does. It's about a woman leaving a job, discussing a bizarre incident where a man she didn't know called a training meeting--or so she thought. The man kept on talking and talking, keeping the workers there for 17 hours through the sheer dint of his charisma and the horrific things he was saying. There's no real conclusion here, despite the fact that she was getting phone calls from the man at home. It's P.K. Dick by way of H.P. Lovecraft, and features one of many menacing but superior intelligences in Cockle's comics that are encountered but cannot be resisted. The rest of the comic contains snippets from interviews regarding the craft of writing, the craft of drawing, the effect of criticism and cut up maps: annotations without direct connections to source material. Cockle seems more and more adept at matching image and story, with the thick blacks and sketchy character design of "Exit Interview" being a perfect example. His mix of dread and absurdity is a potent one, especially when he doles it out to the reader in such small doses.

SF #2, by Ryan Cecil Smith

This series has touches of both the past and the future, given its nostalgia-inducing Risograph print quality and its cutting-edge storytelling techniques. Smith's manga influences are unfortunately beyond my field of expertise, but what's clear is that he has a stunning mastery over the page and knows how to create the sort of chaotic and cartoony environment that's the hallmark of much manga work I've seen. It's printed on cheap paper that soaks up the blacks nicely, adding to that sense of reading a comic tied to no particular time despite feeling like it belongs to multiple eras. His cute character designs are a perfect complement to the detailed and naturalistic backgrounds, just as his humorous asides and quirky dialogue are a perfect match with what is otherwise a potboiler space-opera plot. Smith is obsessed with universe-building, introducing character after character to create a highly-detailed, lived-in environment that the reader is introduced to along with Hupa Dupa, the orphan who is adopted by the titular Space Fleet Scientific Foundation Special Forces. Smith telegraphs to the reader that he has a mysterious secret that even he doesn't know about while keeping him an everyman sort of character. This was easily the best genre comic I read in 2012, one that was light in its conception and densely rewarding in its execution.