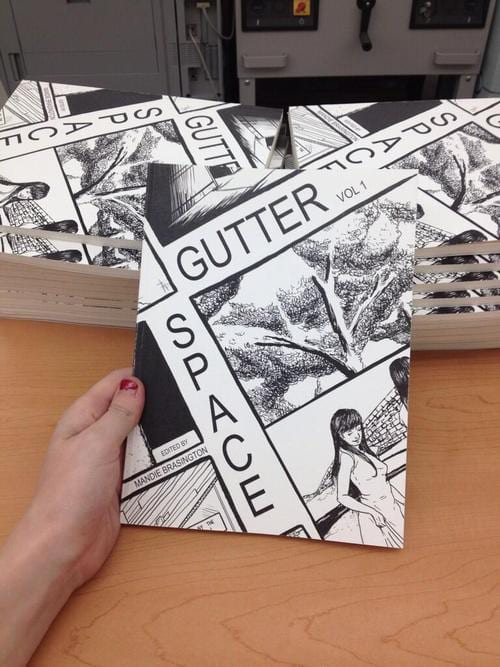

I was excited to attend Autoptic this year in part because it gave me a chance to meet and sample the work of a number of cartoonists in the burgeoning Minneapolis scene. Certainly, I was already well aware of the work of cartoonists like Zak Sally, Anders Nilsen, Rob Kirby, JP Coovert, Max Mose, Tom Kaczynski, and Will Dinski. I'm also quite familiar with small publishers like 2D Cloud (helmed by Raighne Hogan and Justin Skarhus) and Grimalkin Press (run by Jordan Shiveley). It's not a coincidence that most of these cartoonists were part of the show's steering committee. I was most curious to delve into the work of lesser-known local artists, particularly current and former students from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). Sally and Nilsen both teach at the school, which boasts about fifty students majoring in cartooning out of about seven hundred undergraduates. I found that overall, MCAD's students display a fairly high level of craft in their minis. While I didn't see anyone as of yet at the level of the best cartoonists to emerge from the Center for Cartoon Studies (though there are a couple of promising candidates), the depth of their talent pool is impressive. Let's take a look at a student anthology, Gutter Space, as well as look at the work of a number of MCAD students, graduates, and other local cartoonists.

Gutter Space has a fair amount of strong work. In "Another", "Okay", and "Sleep", Alexis Cooke delves into her near-crippling anxiety with brutal honesty, using a line that's equal parts spare and unnervingly cute. That cuteness is used to good effect, especially when she draws herself with bunny ears but no mouth, trying to convince herself that she's OK. "Sleep" is a more naturalistic, delicately-rendered story where exclamations are literally stuck in people's mouths and a corpse laying in a swamp with a bag over its head is something to be comforted. Cooke addresses horrific imagery in a manner that's in turns direct and then oblique, restrained, and then sharply visceral. Her work was the most impressive in the book.

Alice Woods' comics explore dreams and dream logic, with a chunky line that she doesn't seem to have complete control over yet. Chris Olson creates atmosphere in his short story, but not enough to really stick the landing in just two pages. Eric Munson's stories about "trap suits" (robots that can contain your soul after you die) are both ingenious; one is a murder mystery and the other is a conspiracy plot turned upside down. I enjoyed his weird, tilted parallelogram-shaped panels and boldly-inked figures. Erica Valdez' stories emphasize shadows as a storytelling device, with what looks like a children's story and another story set to the lyrics of "The Long, Black Veil". Her use of atmosphere is sophisticated and clever, even if the stories feel more like formal experiments than fully-fleshed out narratives. Heather Williams and Liz Glein both crafted adventure strips that went in different directions; Williams uses simple rendering with a clever formal structure, while Glein emphasizes character interaction and body language.

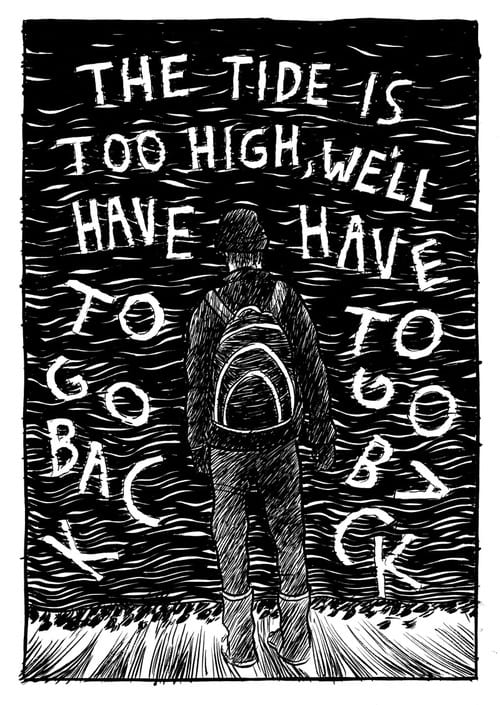

Mayme Thompson's "August" silently tells a story of a couple struggling after the death of their child. She doesn't quite have the chops to pull this off, using images that are too on-the-nose. On the other hand, in "An Atlas Of Monsters" Sarah Evenson uses a strong, immersive brand of storytelling, scrawling out its letters in white against a black background. Clearly influenced by Zak Sally, she makes great use of this style, creating a number of memorable images thanks to her use of negative space. It's clear that some cartoonists simply submitted assignment work and others the first chapter of a longer narrative, but there are a number of personal, powerfully told stories in this book. I'll discuss more of them as I delve into the artists whose minicomics I received at the show.

Jen Silverman: Her two comics, Level 1 and Things & Stuff, represent an artist with a wide range of interests and drawing styles. "Level 1" is a cute, video-game-inspired story about a pair of friends going on a quest to get fast food for breakfast. This is an enjoyable bit of fluff, thanks mostly to a few genuine laughs generated by Silverman's character design. In the latter comic, a collection of short stories, "Pick Up The Phone" stands out with two parallel narratives: naturalistically drawn images of a wolf devouring its prey vs someone regretting that they didn't pick up a call from someone they never heard from again, suggesting a link between the two actions. In "Fetch", Silverman cleverly plays with panel design to give multiple points of view regarding a dog's motion as it chases a ball. "Blackout" is a silent story involving our relationship with technology and silence when we are around others but aren't interested in interactions. Silverman's got chops, to be sure, but I'm not sure she's found a story really worth telling so far. She certainly has every tool necessary to make something memorable.

Kitty Berry: Berry is one of several MCAD cartoonists who is working out issues of identity on the page. The title of this book is what I assume is her birth name, written out in Morse code. The comic is a monologue by Berry about feeling as though the persona she presents to the world is entirely a construct, built by a younger, meeker version of herself. Berry is bubbly, extroverted, and fashionable, which she notes is precisely the kind of person she made herself become: "Kitty", if you will. This comic is a tribute to that "original" self whose name is a forgotten secret, the architect and engineer of her new persona. I very much related to this idea of a "constructed" and "true" self built on extrovert/introvert lines, but in Berry's case the divide seems much more severe and calculated as a reaction to some specific life events. This is a smart, personal, and brutally honest comic. Berry excels at body language and drawing clothes, though her figures are still a bit stiff and her faces on the distorted side. This is to be expected in a comic that's less an exploration of self than an excavation, as she digs up her own secrets. Not only so she doesn't forget them, but so she can comfort them. I'm eager to see how Berry continues to work out this struggle on the page.

Leigh Luna: Luna's characters are always in motion. In An Addiction To Hands And Feet, Luna takes the lyrics of a Regina Spektor song as a catalyst for a brief interlude where she's walking loops around the city, her panels and the text meandering along with the lyrics. In the story "Smoking" in Gutter Space, two friends have a confrontation as they walk through the city at night. In Clementine Fox, the titular character and her other animal friends scramble to go on an adventure at sea. None of these three stories has a real beginning or ending, it's all "middle" as it were, because Luna wants to skip to characters going somewhere and the interactions that take place during such journeys. Luna experiments a bit with line weights in these stories. In "Smoking", she uses a fairly thin line that doesn't flatter her character design; Hands and Feet displays a thicker line and more spotted blacks to lead the eye around the page, which is crucial because of the unusual composition of elements; and in Clementine Fox, she mixes up line weights, giving the characters a bit of fragility with a more delicate line and their surroundings greater density with a thicker line. Luna seems especially interested in character and friendship dynamics, emphasizing a mix of conflict and warmth. That's certainly at play in another Gutter Space story, "Breakfast", which is a series of tight, static images that pans back to reveal a couple at a restaurant. Luna seems ready to cut her teeth on a longer character narrative, and a story involving anthropomorphic animals might suit her best.

Dawson Walker: Walker's name was one mentioned by a number of people during the time I spent at MCAD. It's obvious that he's an adventurous and meticulous artist with a fully-formed style. Autonoetic (referring to "the ability to mentally place yourself in the past, the future or in imaginary situations") details a trip through a blinding snowstorm to a cabin, including a hike blocked by a river that's too deep to wade. Mostly, this is a piece about consciousness and disassociation, as the more densely rendered and intense a page is, the more that the character's consciousness starts to fade from his body. Dawson sells this with a painstaking, gorgeous whirlwind of scratchy black lines and carefully spotted blacks. In Phantosmia, ("phantom smell"), Dawson uses smell lines to wicked effect with a character nicknamed "Neal the Nose" because of his powerful sense of smell. For Neal, the world is a series of assaults on his nose, but he plans to use it to become a detective. His first case: finding out what happened to make his mother leave. He's led into his basement by an overwhelmingly powerful smell to a series of huge canisters and a body wrapped in bandages. The way Walker weaves in drawings of bandages and dense smell lines that take on a corporeal form is ingenious and genuinely unsettling. He seems fascinated by dark corners, secrets and shadows so dense they can be felt. I'm curious to see what he does when he graduates, because he has the talent to push himself to do something truly ambitious, something that incorporates his formal tricks with other storytelling concerns. His style is distinctive enough to become a breakout indie star.

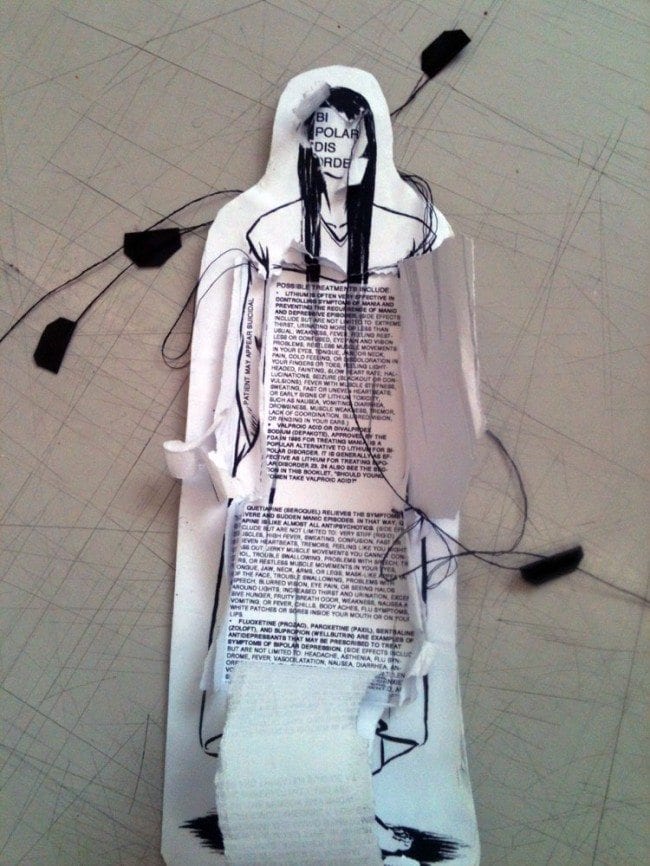

Mandie Brasington: Brasington runs the Dead Cartoonist Society and in general seemed like one of the more ambitious and experimental cartoonists I encountered at Autoptic. She's another artist for whom issues related to mental illness are obviously quite important. In Wall, the character is frightened by her commute, frightened by someone walking by late at night, and generally experiences a high degree of anxiety. What's interesting is that the second voice the character hears in her head (denoted by white text in a black world balloon) gives her instructions that are at once practical and restrictive. That leads to a confrontation in a dream, where she encounters a wall that she wants to break down before the voice stops her, admitting that "it keeps her functional." This satisfies the character, but that is a hell of an admission for a character, to not search back for the particular triggering trauma, at least not while she's still healing. Her other comic is one where the reader has to rip out string that tears up the page, revealing facts about bi-polar disorder. It's a visceral comic meant to mimic the feeling of being ripped apart while dealing with cycling up and down as well as being medicated.

Jaime Willems: The three stories I've read from Willems are all over the place in terms of subject matter. Babies' First Punk Show is an accordion comic with brown cardboard covers meant to mimic a child making their first book. Rendered in a naturalistic style, it details Willems taking two friends to a punk show and realizing that they have never been to one before. The scene where she throws one of them into the mosh pit and describes the positive energy that can flow in such a situation is both amusing and interesting, obviously the product of lifeblood experience. In The Black Rider Act I, Willems adapts the album/story by Tom Waits, William S. Burroughs, and Robert Wilson. Here, her drawing is much more stylized and surprisingly bright, considering the subject matter. It's a story about a man who makes a deal with a devilish figure in exchange for becoming a great huntsman in order to wed his true love. Willems' figures have exaggerated cheekbones and eyebrows, almost as though they were wearing stage makeup. I found it interesting that Willems chose to emphasize the artifice of the story rather than simply dim it with dense crosshatching and lots of blacks. Her story in Gutter Space, "Home", is a dystopian story of one woman's quotidian experience of waking up and trying to go through her day without being accosted by gas-mask-wearing policemen. Willems' variety of interests serves her well, but it's clear she's still searching for a style as she refines her drawing technique.

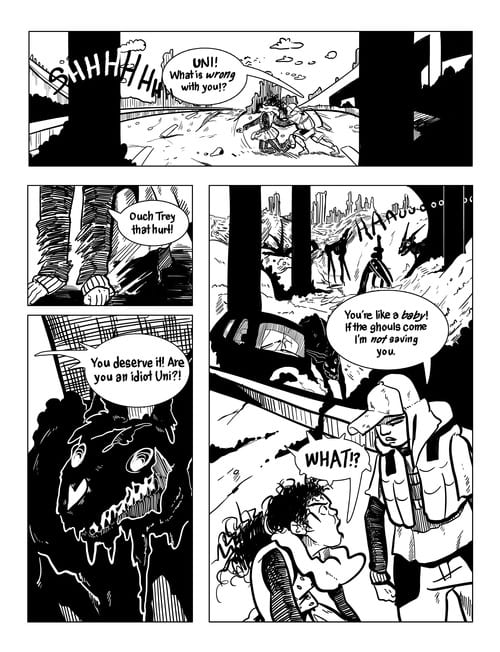

Olivia Johnson: Johnson is interested in speculative fiction, from "The Death of Fafnir" in Gutter Space to Keeps Me Going, a post-apocalyptic story about a brother and sister trying to navigate a wrecked cityscape. The former story is a series of tight close-ups and intricate detail work; at two pages, it's an interesting exercise that finds Johnson experimenting with technique and tone. The latter mini is cluttered in terms of its page design yet is also full of striking images. In particular, the shadowy dog-like "ghouls" are effectively frightening and add an unearthly feel to a story dominated by the two human characters. There's a little bit of Farel Dalrymple in the way she draws her characters and settings, though not quite at the same level of refinement. I sense that Johnson will continue to refine her line as she continues to write longer stories.

Joel McKeen: His mini Afternoon of the Hardly Living and his trio of stories in Gutter Space ("Teddy vs Zombies", "Steinbeck", and "The Gig") all point to an artist who loves comics and loves storytelling, but has yet to really come up with a story worth telling. Comparing cell-phone users to zombies isn't exactly a fresh idea, and having Teddy Roosevelt fight zombies is yet another tired zombie story iteration. "The Gig" feels a bit fresher, as a dog-man and his vampire detective friend embark on a sort of Big Lebowsky-esque shaggy-dog adventure. McKeen is interested in lighthearted fare to be sure, but his art often feels rushed and sloppy, as though he couldn't wait to race through one story to get to the next. McKeen is fine at storytelling, pacing, page design, etc; he simply needs to figure out what he really wants to do and take his time.

Rachel Topka: Her mini Unfortunate Relationships features a quartet of short stories about miscommunication and transformation. She's a great example of an artist who plays to her strengths. Her line is a little on the crude side, so her character designs are on the grotesque and funny side. Her comics where her line is thicker and cruder are more effective than her fine-line stories, but she's equally adept at working a grid or using an open layout. Topka enjoys invoking fantasy tropes, mostly to get at their funny and/or grisly components. "How Centaurs Are Made" is a perfect example of Topka deflecting expectations in a gross and hilarious manner. "Flight of Passion" turns vampire drama into high school-level silliness by way of a Bugs Bunny cartoon, once again turning ugly and weird characters into folks who dominate the page. "Unbridled Affection" uses a callback to the first story and yet another amusingly weird bit of character design to flip expectations and heroics. Topka is a clever cartoonist, and I'm eager to see her do more.

Coryn LaNasa: LaNasa is Tom Kaczynski's intern and he published this clever mini of hers. With a fine, scratchy line, LaNasa tells the tale of a man looking for his kidnapped daughter, only to find that the lands he traveled through to get her cause him to not only forget what he's doing, but also sees him joining a group of goat-headed creatures and becoming one himself. There's an elegance in this minicomic, aided in part by Tom K's simple design but mostly due to LaNasa's expressive and jagged line and open storytelling technique. Indeed, her use of negative space toward the end of the story only heightened the sense of tragedy for the poor father.

Alumni and Others:

Caitlin Skaalrud: I've reviewed her work here before, but I wanted to mention her remarkable Houses of the Holy comic. I've rarely seen a comic that so deftly merges its decorative, metaphorical, and poetic aspects. It's a densely rendered comic that follows a young woman reading a book titled "How To Walk Through Fire". Stripping herself naked yet strangely neutered, she pulls up a trap door and unlocks the heavy doors in the basement, one by one. Narrating what she finds in each room in an obliquely poetic style, Skaalrud is sharing a deeply personal howl with the reader, encoding her fears, hopes, and other feelings in each of the rooms before hesitating before room X, and returning to a prison cell with a broken heart before she burns it all down. While there's a cathartic quality to this comic, it's not a joyful one, but rather relief earned at great price. It works because her drawing is so sharp and visceral, and the shock of that nude figure is so incongruous. While I've liked her other work quite a bit, this comic is a big step forward, working on a comics-as-poetry level that reminds me a bit of John Hankiewicz.

Sean Hartman: His comic Angelic Blade represents the crazy, underground, anything-goes sensibility that's not present in most of the work of the other MCAD artists. I can't quite figure out Hartman's visual references and inspirations, other than to say that his work is highly stylized, angular, and grotesque. The comic is about a popular rock duo (Angelic Blade) who happen to also fight crime. The story involves them fighting with their arch-rivals (a group named Rival Blood) and a body-building, steroid-peddling ring, all while filming a music video. Pretty much every page is over the top in one way or another, with the action climaxing with a drugged-up rhinoceros eviscerating the main villain. The tone here is more silly than transgressive; it's less Ben Marra (though that may be a touchstone) than it is an amped-up Jem and the Holograms.

Bart King: This 2001 grad's The Pennsylvanians shows an artist with a smooth, fully-developed style and a quirky sense of humor. This first issue of what will be a longer series is about aliens suddenly popping up in people's homes, simply to watch them. The couple in this comic find that the alien sticks around in order to stare at a light bulb, watch them in their sleep, and eventually play with their dog. Mostly intangible, King portrays them as a kind of waking hallucination that the entire world is experiencing. That experience is certainly creepy for a reader (especially since they're drawn to look like "greys"), even as the aliens don't seem to actually do anything--until one imitates one of the characters at the end of the story. King is a confident draftsman and solid storyteller, and his naturalistic style is a perfect fit for drawing something so weird and foreign both to the characters and the reader's eye.

Jay Rasgorshek: Rasgorshek just graduated this past May. Summer Time is a journal comic about a summer romance with an expiration date. What's clever about it is not so much the romance itself, but the process that allows both parties to surrender to the relationship even though the female partner has a long-distance relationship on the rocks. Rasgorshek compares the way that emotions can grow and mutate to the way nature finds ways to adapt to its environment and even thrive under strange circumstances. I like the way Rasgorshek uses the grid here, rarely deviating from a nine-panel set-up. He makes sure to have his center panels be memorable images: a carnivorous plant, a picture of the woman he was involved with, gears in motion. He memorably breaks from the grid on the final page of this short mini, with the bottom panels merging into one as she departs. In terms of the drawing, Rasgorshek either rushes things or doesn't quite have the chops to pull off some of the things he is trying to draw, especially machinery. Still, this is an interesting and thoughtful take on something very personal.

Phil Thompson: His mini Night Police is based on an idea he had when he was nine years old (and no doubt drawing comics with his older brother Craig, who does a pin-up in this comic). The premise of the book -- that the "night police" keeps falling asleep during his shift -- gets sillier and funnier when we learn just what passes for contraband in his city, and what the dangerous group of "rappists" are up to. It's a comic that has a little-kid's sense of logic and a professional's polish and grasp of storytelling. Thompson is really funny as he tweaks cop-show conventions while never straying too far from his core concept. He seems to have really found his niche as a cartoonist and I hope to see more work like this from him.

Ryan Lower: Canned Goods and For The Joy That Was Set Before Him are both grim post-apocalyptic tales that are downbeat for different reasons. The former is about living in such a world comfortably but with no human contact or meaning to life at all. The latter is reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy's The Road in that it involves a father and son trying to survive in such an environment. For The Joy is about a father and toddler son sleeping and camping out in the wild, trying to dodge uniformed thugs and their firepower. It's about the intense, desperate need to protect one's children, no matter what. The former comic notably uses an internal monologue for the lonely character who is waiting for something, anything to happen. The latter is entirely silent, allowing the fluidity of Lower's storytelling to take precedence as we flip from scene to scene that are alternately warm and frightening. For The Joy was certainly the more interesting of the two comics, as his drawing just wasn't as interesting to look at in Canned Goods, nor was the monologue very memorable. Indeed, Lower could have told roughly the same story in just four pages. On the other hand, the rhythms of For The Joy more than justify its length, as the reader can't help but keep paging through tonal shifts to find out what ultimately happens to this loving family.

Jason Loeffler: The Bear is an intriguing, minimalist comic told mostly in shadow and scratchy figures. It depicts a bear happening upon a couple of hunters and their dead prey, and what happens afterward. Loeffler keeps the reader guessing by shifting the perspective of the comic several times, as the reader sees through the bear's eyes on some pages, the reader sees the action from above on others and various other disorienting angles on other pages. This made the comic difficult to parse at times, but a couple of readings of the comic were rewarding as it became easier to see just what was happening. Loeffler manages to make this comic both restrained and visceral in its storytelling.

Scotty Gillmer and Carl Thompson: My Snobbery Is Killing Me was written by Gillmer and drawn by Thompson, this is quotidian autobio in the vein of Harvey Pekar. The general smoothness of the anecdotes actually reminds me a bit of what Jonathan Baylis is doing in the comics that he's writing. There's a very practiced sense of craft that goes into each anecdote, polishing it up to make it as readable as possible. So while the anecdotes are personal, they have the feel of someone saving up their best, funniest stories to tell you rather than Pekar's method of deliberately telling stories of everyday life as he lived it. Getting that across was more important to Pekar than telling an interesting story with a specific beginning, middle, and ending. That said, Gillmer is quite funny and does get across a number of things that matter to him. The titular story, for example, talks about how important movies are to him and the specific experience of watching them in a theater, dismissing people who don't watch a movie all the way through or who do it on tiny computer screens. After pontificating about that, he then buys a ticket to a crappy action movie. It's a good punchline, solidly delivered by Thompson, who frequently aids Gillmer's storytelling goals by adding in eye pops and exaggerated characterization in the form of distorted body language. Their collaboration definitely has some chemistry, but I'd like to see Gillmer get a bit more raw and ragged in the kinds of stories he chooses to tell.

Scotty Gillmer and Carl Thompson: My Snobbery Is Killing Me was written by Gillmer and drawn by Thompson, this is quotidian autobio in the vein of Harvey Pekar. The general smoothness of the anecdotes actually reminds me a bit of what Jonathan Baylis is doing in the comics that he's writing. There's a very practiced sense of craft that goes into each anecdote, polishing it up to make it as readable as possible. So while the anecdotes are personal, they have the feel of someone saving up their best, funniest stories to tell you rather than Pekar's method of deliberately telling stories of everyday life as he lived it. Getting that across was more important to Pekar than telling an interesting story with a specific beginning, middle, and ending. That said, Gillmer is quite funny and does get across a number of things that matter to him. The titular story, for example, talks about how important movies are to him and the specific experience of watching them in a theater, dismissing people who don't watch a movie all the way through or who do it on tiny computer screens. After pontificating about that, he then buys a ticket to a crappy action movie. It's a good punchline, solidly delivered by Thompson, who frequently aids Gillmer's storytelling goals by adding in eye pops and exaggerated characterization in the form of distorted body language. Their collaboration definitely has some chemistry, but I'd like to see Gillmer get a bit more raw and ragged in the kinds of stories he chooses to tell.