Mark Newgarden:

Maurice Sendak wasn’t the first modern picture book maker to re-integrate the comics medium into the proceedings, but he was probably the one that made it possible for cartoonists like me to get a decent shot at it, decades later. The book was In the Night Kitchen, and for my money, he nailed it.

I grew up with his books, literally from day one. I was Pierre (I didn’t care). Sendak gave me my first literary role model at age zero. And he soon became one himself. My dad was casually acquainted with Sendak and there was a household legend that they had once discussed publishing a children’s magazine together. It probably never went any further than grownups-with-alcohol banter, but it was a heady story to grow up on.

The most important thing about him and his work can be summed up in a headline the Guardian ran with in an interview last October: “Maurice Sendak: I refuse to lie to children.” This might seem sort of obvious but of course it is really anything but. In 2012 when children’s literature is, as often as not, as calculated, pre-formatted, and nutritious as the latest Happy Meal, the issue of what is true— and brave—and right— to actually put into the books themselves can easily get lost between the word count and price point.

Very few others ever did as pitch-perfect, emotionally-connected picture books as Sendak. Whether he actually made them for kids at all, or for himself as he sometimes claimed is moot. He knew exactly what was important, page by page, at all times—better than the editors and publishers and marketing departments and parents and librarians and critics and awarders and all of the other pseudo-superfluous grownups who stand between a children’s book author and his reader. That he was able to do it so well and for so long now seems nothing short of miraculous.

—————————

Mo Willems:

Even if Maurice Sendak (or Morose Sendak as James Marshall reportedly called him) had never created Where the Wild Things Are, he would be in the pantheon of great illustrators for his direct, dynamic draftsmanship (particularly his ink work in the 1950s). His originals are tremendous, all the more so as he usually drew and painted at half the size of the published work.

Where the Wild Things Are is rightly considered the pinnacle of children's picture books, for its structure, draftsmanship, and content. Certainly, I used the book as a template for my first effort, Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! Where Sendak increased and decreased the size of the drawings to indicate the slide of emotion from reality to fantasy and back to reality, I used colored backgrounds to underline the character's emotional state. If you’re going to steal an idea, steal from the best, right?

It is a book that, when deconstructed, teaches you that good design is good storytelling, that it works best on the subconscious (when you notice it, the potency disappears), that posing and strong silhouettes create motion and emotion, and (most importantly) that childhood sucks.

I am very glad he lived and made the books he did.

—————————

Seth:

Maurice Sendak was one of those artists, like Edward Gorey, who sat at the edges of the cartoon world. Not quite cartoonists, but close enough to have influenced at least one generation of comics artists-- probably more. He was certainly an artist whose work I adored. I truly love those early books he did with Ruth Krauss. And is there any more impossibly exquisite work (and object) than the Nutshell Library? Like those little medieval carvings of a world in a walnut--so perfect you cannot believe anyone actually made them.

I must admit, I didn't really grow up with his books. I have a sense that I did read Wild Things once-- a vague memory of being frightened, at an early age, by those amazing drawings. Certainly I recall reading In the Night Kitchen, but whatever impression it made on me was slim. It did stay in my mind. I never forgot it. I wish I had read more of them.

For me, it was in my early twenties that his books came into my life. Around the same time as Gorey and Addams and Steig and Blechman and Steinberg. Everyone knows that the very best children's books can be as deeply appreciated as an adult as when a child. Often more. That's true of Sendak's work. Terrific stuff. Deep. Playful. Maybe even a bit sad.

Sendak seemed like a character as well. From a distance he appeared pushy, egocentric, increasingly disinterested in the modern world ... a navel-gazer ... crabby. Maybe even self-centered or arrogant. All things that made me like him. His life was an object lesson on how to be a publishing artist, that's for sure.

I never actually met the man, of course. I saw him once on stage (more than a decade or so ago) at one of those "in conversation" events in Toronto. Afterward I pressed a copy of one of my books into his hand and mumbled a few words of praise. I recall hoping that he might actually read it, not toss it in the hotel waste-basket before heading to the airport. Later, as that book looked worse and worse to me, I hoped he had tossed it. Several years after that, R. O. Blechman made some offhand comment to me about my name having passed casually between the him and Sendak. Nothing extraordinary. Just a remark.

Upon hearing that I felt that odd feeling that you never lose--no matter how old you get--a feeling of wonder. A profound sense of the impossibility that such distant mythical creatures -- demigods from your youth (a Sendak or a Blechman ) could have somehow spoken YOUR name when you weren't around! How did it ever happen?

I encourage everyone to read Caldecott and Co., Sendak's book of essays and introductions. That's a good read. That book made as big an impression on me (way back when) as did his beautiful picture books.

—————————

Peter Blegvad:

He and my parents, Erik and Lenore, were on friendly terms in the early 1960s in Connecticut. Fellow members of the community of children’s book illustrators, writers, editors. They saw him in the UK too. I think he was in hospital in Cambridge (was he there to dig the Blakes in the Fitzwilliam?) after his heart attack in the '70s? I think they visited him then.

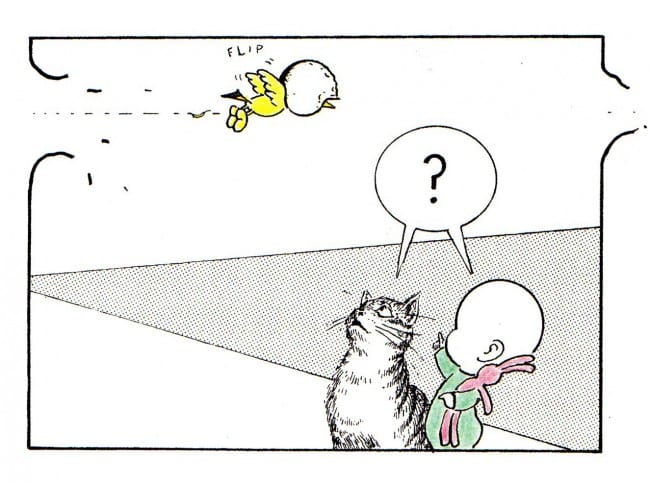

Drawing Leviathan, there was a period when I used the cat in one of Sendak’s “Little Bear” books as my model in several strips.

—————————

Charles Hatfield:

I teach Where the Wild Things Are every time I teach my flagship course in children’s literature. I teach it in other courses too. What this means is that I get to renew my acquaintance with the book in an intense way several times a year. I reread it a lot.

There’s nothing original about choosing Wild Things for a children’s literature course. It’s an old choice. Maybe it’s a stale choice. Sometimes I chide myself for getting stale, and tell myself that I’m going to swap Wild Things out in favor of some other, less familiar book.

I never do.

The truth is that Wild Things draws me like a moth to candle. The reason isn’t just that I find it delightfully, endlessly provocative—a book simultaneously so definite and yet so ambiguous, so eager and light-footed and yet so dark and fearsome. The reason isn’t just that Wild Things is an endlessly provoking Rorschach of readers’ attitudes, assumptions, and tolerances. Those are some of the reasons. But another reason, and one that always outpaces my desire for novelty and change, is that Wild Things is the teachable picture book par excellence—a book that contains so many potential lessons in it. By lessons, I mean useful provocations. More than that, Wild Things contains within it a whole picture storybook tradition.

The miracle of Sendak stemmed partly from his understanding of that tradition, which was historical, critical, even curatorial—but not at all scholastic in the starched-collar sense. Sendak knew the tradition in which he was working: not simply as a market genre, nor as a careerist niche, but as a shimmering, dynamic, ever-adjusting tradition in which he was proud and happy to work. When he won the Caldecott Medal for Wild Things the better part of a half-century ago, he gave an acceptance speech that not only unveiled some of the memories that inspired the book but also sang the praises of the artist for whom the Medal was named: Randolph Caldecott, the Victorian genius whose visual-verbal repartee and rhythmic gusto Sendak eagerly sought to make his own. Sendak’s appreciations of Caldecott—reprinted in his splendid book of essays, Caldecott & Co. (1988)—reveal an artist-critic ensconced in a tradition that, even as he celebrated it, he was busy changing. Sendak clearly loved picture books and illustration, heart and soul. His critical appraisals were acutely observed and keyed to the subtleties of form, but also animated by a pure, bounding delight. He reveled in drawing, the rhythmic exchange of word and image, and sheer creative troublemaking.

If formalism gives Wild Things its structure—a tug o’war between word and picture, superego and id, mom and child, domestic reality and far-flung fantasy—then that quality is offset by Sendak’s fearless depth-sounding of the inadmissible, inarticulable feelings that nearly carry Max, his child-protagonist, away. Sendak’s formalism serves to give shape—not only at the level of the page, but even at the level of entire book design—to feelings that, until Sendak, picture books had hardly registered, feelings of rage, loneliness, thwarted autonomy, and the desperate need for love. I’m not talking about “love” earned through some disciplinary calculus that seeks to impress its grinding lessons on the child—apologize, say you’re sorry, don’t act out—but love given openly in spite of our essential fucked-up-ness.

From my teacherly perspective, which I admit leans toward ruthless pragmatism, Wild Things has many potential “lesson plans” in it because it is so many things at once: designingly simple and formally elegant; self-aware about its genre, by which I mean historically grounded yet innovative; ambiguous enough to lure readers into so many different judgment calls; and, perhaps above all, affirming and challenging at the same time, teasing out how we feel about brattiness, selfishness, discipline, a parent’s love, the urge to dominate, and the urge to give in—in fine, about childhood as we’ve come to know it. I can ask students to read this book to one another and thus observe its rhythmic visual/verbal exchanges; to write or recite its text from memory, thus to catch its poetry; to compare it aesthetically to a late Victorian toy book by Caldecott; to think about why the book’s unseen mother is its second-most important character; to disclose how they feel about the book’s resolution (definite? open-ended?) of the mother-child conflict; to compare and contrast it to a range of post-Sendak picture books dealing with similar conflicts and feelings, from Molly Bang’s When Sophie Get Angry—Really, Really Angry… to David Shannon’s No, David!; to interpret the book as sentimental or fierce; in sum, to reread the book again and again for weeks, admiring its grace or confronting its terrors. It is a great, inexhaustible treasure: the quintessential late-twentieth century American picture book.

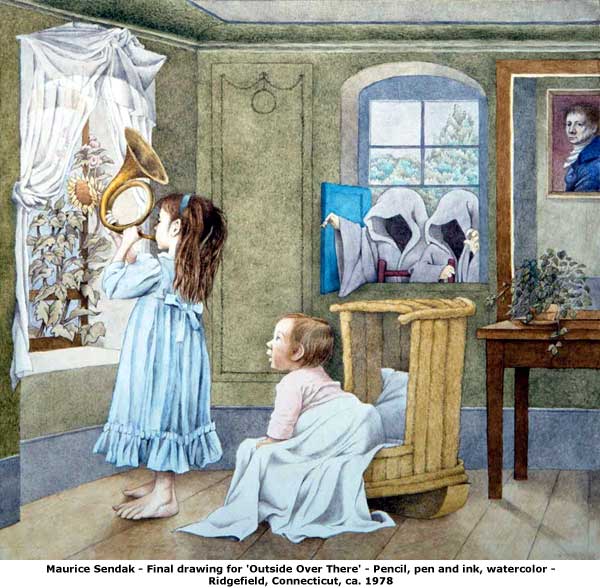

Sendak did beautiful, affecting work before Wild Things; a survey of his career to 1963 alone would be impressive. (My wife introduced me to the unaffected schoolyard delight of A Hole Is to Dig, Sendak’s first great collaboration with Ruth Krauss, published in 1952.) But Wild Things was the book that unlocked Sendak, freeing him career-wise. This was not only because of its marketplace success—Sendak once quipped that Max was the best kind of child, the kind who allowed his parent to do whatever he wanted—but also because it overturned the last vestiges of obliging timidity in his work, uncorking the dark and unabashedly personal stuff that now defines him. Sendak would later pursue this dark stuff into openly self-indulgent crypto-autobiographical territory, from the McCay-inspired dream comic In the Night Kitchen (1970), with its balancing of homey delights and childhood nightmares, to the frankly chilly, almost frozen Outside Over There (1981), an uncanny horror story about a changeling. Wild Things helped bring many great and startlingly personal books out of Sendak, from Higglety Pigglety Pop! (1967), a fable based on the life of a beloved dog, to We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (1993), a satiric riff on mega-capitalism based on two traditional nursery rhymes, to the Holocaust-haunted Brundibár (2003), his collaboration with Tony Kushner based on Hans Krása’s children’s opera, which was performed at Terezín (Krása was murdered at Auschwitz, dying in a gas chamber). Kushner and Sendak engineered a revival of the opera as well. Who else has had a career like that? Wild Things was the passport that led to all these boundary-shattering works, as well as Sendak’s design work for operas and ballets, starting on the cusp of the 1980s with a stage adaptation of Wild Things itself.

Sendak, then, was a genuine Renaissance man, whose interests could not be neatly corralled into one tiny box (genre, style, medium). But for me the heart of his achievement will always be his picture book children, those squat, feisty urchins, full of vinegar and fire: feisty, anti-authoritarian, and, yes, wild. He paid tribute to their imaginations by unleashing his own fierce imagination, untrammeled, boundless, and free. Wild Things is the turning point in that story.

Sendak is that rare artist whose pursuit of self-indulgence liberated and humanized an entire field, extending its horizons and enriching its emotional palette. Against pinched, hidebound ideas about what children's book could do, he depicted childhood in all its confounding mystery, unfogged by sentiment and invested with fear, fury, and joy. His understanding of the picture book form was so complete, his reverence for its history so genuine, that he became America’s greatest practitioner-critic of children's books. His understanding of the human heart was greater still. He was, in short, an incandescently bright star—and Where the Wild Things Are, I believe, is the thrumming heart of his achievement.

I just can’t seem to get away from that damned book!

—————————

Lauren R. Weinstein:

Few people know how to tap into a child’s deepest emotional life and shape his or her subconscious forever. Maurice Sendak did. My favorite book of his is Outside Over There, and the reasons why keep changing as I get older. In the Night Kitchen and Where the Wild Things Are seem to explore primal urges and dreams, and are resolved by the characters waking up, or going back to their mommies. I love these books, but in Outside Over There, there’s more at stake.

A baby sister is kidnapped by goblins. The baby is replaced by a changeling made of ice (the scariest thing I could imagine when I was a kid). The mother is absent—waiting for her husband who’s away at sea. Our hero, Ida, probably four or five, has to save her sister using her will, her mother’s cloak, and her wonder horn. The goblins happen to be disguised as babies. Ida entrances them by playing the wonder horn, making them dance so fast that they dissolve into water. Few people could draw this transformation with such naturalism. In the end, Ida is charged with the responsibility of raising her little sister, while her mom stares off to sea, waiting for Ida’s papa to come home. When I was a child, I looked up to Ida. I marveled that a girl could be so brave and save her sister. I longed for one of those big flowing night gowns, and I wanted a sister.

The drawings in this book changed my life. I scrutinized the sunflowers growing up and up and the facial expressions of the portrait in Ida’s room changing slightly. The German Shepherd. The musician and the sailors hidden in the compositions. Sendak’s inspiration seems to have been German and Netherlandish engravers. These drawings don’t take any short cuts. They are very rendered, but carry an emotional weight.

Do I identify more with this book because the main characters are girls? Possibly. The story seems to be more about girls, and what is expected of them. If the protagonist was a boy, would he be expected to raise his younger sibling? Ida has big feet and flowing hair; she’s going to be tall and gorgeous. She’s more in control of herself than the boys in Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. She has grace.

Now we read this book to my daughter. She’s 2 1/2 and I don’t know how much of it she gets, but she wants to hear it over and over. She thinks the goblins are aliens. Maybe she can just tell how enthusiastic about the story I am. Sendak knows he can take children to these dark places, but he builds in the security of the adult reader guiding them along. This book takes childhood seriously. It talks about love and responsibility and heroism, in a way that is never spelled out. I read somewhere that he revised the book over one hundred times, and it shows. It reads like Yeats, like perfect poetry. I don’t mind reading it over and over again to my daughter, always marveling at new details in the drawings.

—————————

Sergio Ruzzier, children's book author and Sendak Fellow:

I miss Maurice's voice and I miss his hugs. I miss walking with him and sitting on a stone wall to rest and chat. The last time I saw him was the day before the night he died. He was sleeping peacefully and it feels good to remember him like that.

—————————

Michael DeForge:

—————————

Megan Kelso:

While I agree that Maurice Sendak's work deserves its place in the picture book canon, I feel lucky that I got to discover his books on my own. The imaginary world that feels real---equal parts terror and delight---- belongs to childhood. Only a very few adults retain a grasp on it the way Sendak did. I think having your first grade teacher (or your mom) introduce you to Sendak's vision of that world somehow diminishes its power. In kindergarten, soon after I learned to read, I remember going to the library on my own during lunch recess; a respite from the stressful routine of Boys Chase the Girls/Girls Chase the Boys. I remember finding Where the Wild Things Are on a low table stacked with picture books. Max seemed a little older than I was. I did not identify with him, but the book shed some light on the mysterious, somewhat frightening behavior of boys. My favorite part of that book is when the smell of supper lures Max back to his room, so cozy and prosaic after his big adventure. If I were an elementary school teacher, I too would probably not be able to resist reading the gorgeous, perfect prose of Where the Wild Things Are aloud, but I also think that book, and most of Sendak's work is meant to be read, and pored over, in solitude. And on a final note, how did Sendak manage to make his simple drawings of food seem so delicious? I think all my favorite Maurice Sendak moments are food related. I love that overflowing pot of noodles when the Alligators are making macaroni ….and in Chicken Soup with Rice, my favorite drawing is when the March wind knocks down the door, blows the soup off the table and proceeds to greedily lap it up and roar for more. I wanted to climb right into those illustrations, live in the funny old houses with Max, Pierre, Johnny, and all the little dogs. When I reached the point with my own drawing where it occurred to me to copy what I admired, Sendak's were it. May his work live forever, quietly, on library shelves, waiting for children to discover it.

—————————

Dylan Horrocks:

When I heard Sendak had died, even though I knew from interviews he'd given that it was coming, I was hit by the news like a physical shock. It was like when Charles Schulz died. It's not just because Sendak made such great books (and they really were incredibly good - from the tiny Chicken Soup With Rice to the extraordinary Outside Over There). It's because - in his work and in interviews - he was utterly painfully candid and honest, full of rage and passion and intensity, compassion and love. He was angry and he fought with life, and life took him to some very dark places. But for anyone who's ever been a frightened, angry, crazy child (i.e. everyone), Sendak was on our side; he was fighting on our behalf. He was just so goddamn present in the world. And now he's not.

There are things he said in interviews that will always stay with me: "I refuse to lie to children," he said. Then there's the story he told about a young boy called Jim who loved the drawing Sendak sent him so much that he ate it ("That to me was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.").

Of course, it goes without saying that so many things he wrote and drew will stay with me too. Sendak's books changed everything. Everything.

Maurice Sendak is one of THE great writers and artists of the twentieth century, in any field. And if anyone disagrees, I'll fight 'em! In a parallel universe, he'd have won the Nobel Prize. But then, the Nobel Prize is nothing next to that small boy who ate an original Sendak drawing for sheer joy: "We'll eat you up, we love you so!"

—————————

Cathy Malkasian:

Maurice Sendak seemed destined for an agonizingly full life. He was a special kind of bug, with antennae tuned to suffering and humor. In every careful line, every thin subtraction of light he used to shape an image, there's a bit of sorrow at the beauty of living and loving too well. His complete honesty—in line, print and speech—can leave you feeling both empty and full. He seemed to understand that oscillation well, and somehow thrived in its fine frequency. His work can look playful and buoyant, but it is heavily weighted, too, and deeper than some parents might be willing to accept. But he wasn't writing for parents, or anyone who had learned how to be sensible. He was appealing to that very real oscillation—of dark and light, empty and full, terror and bliss—from which children don't necessarily want to flee.

—————————

Victor Kerlew: