Dan Dare is an aspirational comics-based figure once created to entertain young boys that has since grown to become an all-purpose symbol of what is meant to be “good.” It makes that particular British strip a natural target for deconstruction and re-interpretation. The space-ace hero first graced the world of comics within the pages of Eagle comics magazine (actually, he graced the cover and some inside pages), and he was a regular feature since the magazine’s launch on April 14, 1950.

Ever since, he has been recycled and recreated endlessly in the world of British comics. He never quite landed outside the United Kingdom in terms of popularity, and he's certainly never broken into the lucrative American market, but Dan Dare has always carried enough nostalgic weight to justify yet another attempt. With the character’s 70th anniversary fast approaching, it is time to look at some of the more notable versions that filled the funny papers throughout the decades.

The original Dan Dare is notable for a lot of things, but to me the most interesting thing is the counterintuitive method of its creation: a lavish budget, a full studio, a team of four assistants, photo references galore, and the scientific advisory of famed science fiction writer Arthur C. Clark. All of this? To draw two pages per week. This seems so out of bounds with the realities of commercial comics at the time, and even today, one wonders how it could have lasted. The answer is, of course, financial success. The first issue sold 900,000 copies, and by the time the title died in 1969, sales fell to a dismal 150,000 copies in Britain alone – enough to make it a number one title in the American market today.

Still, it wasn’t just a question of profit. Eagle’s founder, the Reverend John Marcus Harston Morris, pursued the highest standards in his creation. He created Eagle as a counter to American publications, which he saw as "comics that bring horror into the nursery." His publications were to be comics with strong ethical sense that would install in every fiery youth the qualities of courage, loyalty, fairness, and patriotism. Illustrator Frank Hampson was hired by the Reverend to help curate the magazine and its star attraction strip.

The original run of Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, republished by Titan Comics in a series of hardcovers, gives us an alternative history of the 1990s, the decade in which the story is set. I’m not talking about the advance gadgetry or the space flights to the edges of the solar system. Rather, this is a reality in which Britain flourished after World War II and secured a dominant position in the new United Nations. Here, England still rules over the world (with a velvet glove, of course), as it did in the days of the empire. The series might refer to a United Earth, but it’s quite clear to any Union Jack-loving reader who calls the shots.

The French and the Americans, in the form of Dare’s co-pilots Hank and Pierre, are valuable allies – but always second in command. Likewise, allies Digby, Dan’s orderly, and the female Professor Peabody show the possibility of some social reformers without ever crossing a line that would appear scandalous in the 1950s. Digby’s working class approach keeps him as a perennial comic sidekick, and we’re only allowed one woman scientist while the upper brass remains all-male.

The first story arc, the massive Venus Campaign, can be read as justification for empire-building. Overpopulation means Earth’s governments lack the resources to feed everyone, and Space Fleet sends ship-after-ship to Venus, trying to discover if the ground is fertile enough to grow food. When Dan and company. arrive, they discover the land is good, but it is also inhabited. There are three local races, including the evil Treens, under the command of Dan’s most popular villain – the big-brained Mekon. Not that the local population bothers our heroic explorers too much. That land is already as good as theirs: “And it’s pretty obvious the Venusians don’t need [all the land]. Look at it going to waste in all that jungle down dare” (October 6, 1950).

I don’t know about you, but it brings to my mind Ayn Rand’s infamous notion regarding ownership and use of land. Civilized countries respect land ownership overall. It is the foundation of personal freedoms overall, but only as long as the right sort of people hold the land, and only as long as they use it in the service of capital:

"[Native Americans] had no right to a country merely because they were born here and then acted like savages .... Since the Indians did not have the concept of property or property rights – they didn't have a settled society, they had predominantly nomadic tribal "cultures" – they didn't have rights to the land, and there was no reason for anyone to grant them rights that they had not conceived of and were not using."

Our protagonists can’t imagine any other use for the land but production that will serve their own needs. They do not consider the possibility that these are sacred lands, or that some interaction of natural forces exists beyond their limited observation. They will win, and they will bulldoze over the “wild” and will make it all “civilized.”

There are other criticisms to be made against the strip. Reading them in the modern large collections they can be a painfully slow experience. These stories were made to be read weekly, and thus a good third of every strip can be used to recap plot elements instead of moving forward. It’s a challenge of form rather than content that Dan Dare doesn’t really pass with flying colors – “The Venus Campaign” aims for ‘epic’ but by its end you might fell more ‘exhaustion.’ Likewise, the more action-y “red Moon Mystery” piles events one after the other in an attempt to keep the reader’s interest, but the attitude of the storytelling naturalizes any sense of danger. Of course we know Dan would survive, the effort is to make us feel the threat – but it’s all rather bloodless.

Still, they are a piece of comics history and might be recommended for their illustration prowess alone: Hampson, and his colleagues, attempted to keep things toned-down in terms of the science fiction and there’s a lot of technical stuff that is sure to excite any gearhead. Whereas many science fiction strips of the day (and let us be honest, of this day as well) treat the science as an afterthought, it is satisfying to see the art respect the improbable nature of these rockets and ships.

Early Dan Dare stories did respect their craft, and thus, their readers as well. There’s a real ‘spared no expense’ sense to these tales with their neverending parade of background, complex machines, large scale battles and ever growing cast – all while trying to adhere to a degree of realism (or, at least, probability). These qualities, which made the strip and character so popular are exactly that which fail to appeal to me, on a personal level. Dan’s just too good and nice to be an exciting action hero, all these apocalyptic explosion around him and he fails to even blink. Just chin-up all the way.

All of this meant is I was actually quite happy to get the next incarnation of the character, which have felt like quite a slap in the face for all the older fans: The Eagle carried on for almost twenty years before shutting its gates (for the first time) in 1969. Dan Dare fell into disuse for almost a decade, until the strip was revived by the newly launched science fiction comics magazine, and the moral antithesis of everything The Eagle stood for: 2000AD.

Arriving with the first prog (issue) of 2000AD, Dan Dare doesn’t seem to fit in. Launched to capitalize on the expected popularity surge in science fiction following the release of Star Wars, and brought to life by young firebrands Pat Mills and John Wagner, the old man was ill-fitting to the new world of the 1970s. Other strips introduced in that issue included the hyper-violent time travel story Flesh, brutalist spy serial MACH 1, the class-conscious occupation-narrative Invasion! (which featured the Prime minister shot on the page and almost got the publisher in hot water with the USSR), and the black cast of the Rollerball-inspired Harlem Heroes. The biting satire of Judge Dredd was to follow just one week later.

Arriving with the first prog (issue) of 2000AD, Dan Dare doesn’t seem to fit in. Launched to capitalize on the expected popularity surge in science fiction following the release of Star Wars, and brought to life by young firebrands Pat Mills and John Wagner, the old man was ill-fitting to the new world of the 1970s. Other strips introduced in that issue included the hyper-violent time travel story Flesh, brutalist spy serial MACH 1, the class-conscious occupation-narrative Invasion! (which featured the Prime minister shot on the page and almost got the publisher in hot water with the USSR), and the black cast of the Rollerball-inspired Harlem Heroes. The biting satire of Judge Dredd was to follow just one week later.

Compared to these, Dan Dare immediately felt like the oldest man in the room, a geezer who was only there because management insisted (there are conflicted versions in the various histories, but there seemed to have been a belief that a movie was forthcoming and securing the rights was the smart thing to do). The solution of the initial creative team, writers Ken Armstrong and Pat Mills and artist Massimo Belardinelli, and all who followed them were to pretty much remake the character from scratch. They kept the name and idea of space adventuring hero (as well as classic villain, the Mekon) while tossing away everything else.

This Dan was not the favorite son of the space fleet, but an angry action-oriented loner who balked at his superiors and preferred to solve all his problems with a fist, a ray gun, or (personal favorite) a living, blood-thirsty axe. True to the 2000AD-type, his adventures begin without a pause for explanation. Nobody even bothers to explain how Dan Dare made it to the year of 2177, with Dare’s crew being killed by a new alien weapon. When his own command refuses to believe him, Dan takes a spaceship and ends up being chased by both sides. As typical for a Pat Mills protagonist, there’s a direct rejection of any authority, and the focus is on the action and excitement. Mills’s pet theme of class-warfare is pushed to the background. Dan Dare is no Bill Savage, but you can see echoes of his usual interests in the distance between the chair-bound command, all smooth and shiny and distant from the actual dangers of the universe, and rough and ready protagonist.

This is Dan Dare in name only, something that is actually acknowledged in the introduction to the reprint collection by writer Garth Ennis. “[This was] not Frank Hampson’s original creation from the 1950s Eagle, far from it,” he wrote. “This was a different beast.” This is not a deconstruction or an intellectual examination of the problematic issues with the original creation (these would come later). What we have here are some angry kids being forced to play with toys they don’t particularly like and just doing whatever the hell they wanted. Someone gave them a Ken doll, so they fashioned him a Mad Max-inspired armor and a Mohawk. In one story, Dare gets to meet up with old enemy who cannot bring himself to believe this new figure is indeed the same as the clean-cut figure from the past, with superimposed drawing done in the old Eagle-style atop the new design.

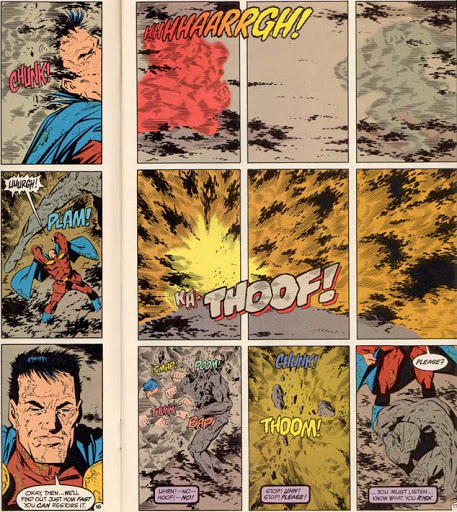

While it must have been shocking, damn near heretical, to any of the old-school fans, the simple fact of the matter is that it worked. True to 2000AD’s mission statement, every chapter of the initial serial is forever rushing forward in a surge of action. While this version of Dan Dare went on to feature the talent of Dave Gibbons (and, arguably, being the place where he honed his controlled and bold style), the best parts of it can be attributed quite safely to Massimo Belardinelli. Already a familiar name by the time 2000AD came into being, the Italian-born artist worked on a long list of projects for British publishers but never seemed to become a fan favorite as other early artists, possibly because his style appeared a bit old-fashioned compared to the likes of Gibbons, Mick McMahon, or Carlos Ezquerra. A talented draftsman for sure, but also someone who was often just “there,” without imparting too much impact.

But, for my money, Dan Dare was his high point. It’s such an over-the-top violent fantasy, the imagery seemingly taken from the pages of Metal Hurlant (especially the living ships and the massive space battle as the story nears its climax). It is hard to do anything but grin at it. There’s monsters and aliens, space battles, punch’em ups, and screaming living axes. Really, it is everything a boy could want. Eagle wanted to educate kids; 2000AD wanted to entertain them, and it’s why this version aged so much better than the original.

The giant, color double splashes that opened every chapter also helped immensely, working in both a highlight reel of the story and a promise of better things to come. It’s the best use of limited color pages allowed by 2000AD at the time, later aped with much success by Pat Mills and Mike McMahon’s Judge Dredd: The Cursed Earth serial. Compared to that, the Gibbons drawn strip, though technically more accomplished, fell like a rather mundane affair – the color is often limited to a single page that is simply used as a part of the story. And while it does wonders to the plotting speed, one cannot help but feel something is lost.

The Gibbons-drawn strips also take the series down a more regimented path, first with an arc reintroducing the classic villain, the Mekon (as written by Steve Moore), and later with the Star Trek-inspired “Legion” storyline, with Dan leading a crew of selected hardcases on a journey across unknown worlds. These are also fun. Gibbons draws with scientific precision that the script never seems to demand from him, but something about them feels tame compared to early stories. Gibbons’s art is almost too good, if you catch my drift, lacking the rawness that gave Belardinelli’s chapters such an appeal. I keep wanting to stop and focus on the details of his drawing, the bolts on the outside haul, the way the space suits fold as people move, the wrinkles on hardened faces, etc. … When I should be rushing forward through every page, eager to see what comes next.

Warren Ellis, in one of his “Come in Alone” articles, talked about the crudeness as part of the charm of these early 2000AD issues – crudeness that was built into the whole package (from the writing to the art to the print quality). And while he was talking through his nostalgia goggles, there is some element of truth to his words. To embolden the early visions of Pat Mills and company, all your work must come with a kick to it. And here’s Dave Gibbons, a ballet dancer of absolute mastery and genteel form. Good on his own terms, but not necessarily what the story called for.

The next big Dan Dare revival came with the relaunched Eagle in the mid-80s. Despite leaving the confines of 2000AD and returning to the mothership, the new Dan Dare strip, back to the usual 2-3 pages of old, brought with it the writing team of John Wagner and Pat Mills. It is an interesting mix, in theory: the old magazine but with a young creative team. At this point in their career, the two writers already developed very distinct voices and approaches to their writing. Wagner was often angry in his writings, but it was anger masked by cynical comedy, exposing the corrupt undercurrent of society by highlighting its faults. Mills was just straightforward revolutionary – his comics filled with working class rage and hatred for the rich that could put any Marxist to shame.

At first, this new Dan Dare seemed like it was going to do something unique: with the hero being the original protagonist’s great-grandson, and the story mostly taking place on Mekon-occupied Earth, giving it a very ‘80s “man-vs.-the-system” vibe. A rather sacrilegious, and seemingly unnecessary (in plot terms), flashback sequence gives the old Dare a new origin story as a time-displaced WWII veteran, despite the fact he’s long-dead by the time this story takes place and thus of little importance. Still, looking forward, instead of satisfying the old, has never been a bad maxim to live and write by.

Alas, instead of being the best of both worlds, this new Dan Dare strip ended-up as nothing more than a competent action-adventure serial, enlivened at first by some great dynamic art from Gerry Embleton and pretty (if less exciting) pictures by the venerated Ian Kennedy. It might be heresy, but I preferred Embleton’s dynamic energy over Kennedy’s perfectionist compositions – though both are a pleasure to look at. There’s a lot more “biff” and “pow” here than in the original story, but after the violent visions of Belardinelli, and the all-out space-action of Dave Gibbons, it feels rather milquetoast in comparison.

It’s as if Mills and Wagner’s instincts canceled each other out, with the result being too often typical and bland. This is a story about occupation and rebellion that feels as endorsed by the establishment as the 1950s version. The most interesting thing about it, in retrospect, are the bits and pieces either writer used or would use in their more personal work: a threatening alien mercenary with flying sharks evokes the Kleggs from Judge Dredd, the over-accented Scottish robo-car has the same basic joke as Strontium Dog.

That version of the character, despite being extremely long-lived (The New Eagle lasted all the way to 1984), has never been properly collected. The only way to find it is through obsessive bin diving or via less-than-kosher websites. This has helped its rather inert legacy. Despite its epic length and the prestige of its creative team, it has become mostly forgotten.

Dare, originally published in the 2000AD spin-off magazine Revolver before it folded prematurely and was later reprinted in regular issue format by Fantagraphics is probably the most ‘80s comic imagined. It’s alternative. It’s revisionist. It’s deconstructionist. It’s angry-young-man-political. It’s written by Grant Morrison just as he was in ascent. It’s also very British, in a way that American audiences surely appreciate, and it’s also quite bad.

At least, the writing is quite bad. Artist Rian Hughes does his best, and some more, with the material given – mining the old strips for a world that is both an exaggeration and a degradation of the original creation. The backgrounds and city-scapes give just the right feeling of something that was once great but has been brought low. These are pop-art comics done right. There are some spectacular action scenes as well, particularly the nasty end of issue #3 with old Digby being gunned down. While every iteration of Dan Dare beforehand has been more strongly defined by the art, this is one in which the visuals totally dominate over the story.

Unfortunately, Morrison’s script is singularly in degradation mode. The story is set in the years after the original strip’s end, and it gives us a sad and broken Dan Dare, who sells his image for new Prime Minister Gloria Mundi (an obvious Thatcher substitute), while reminiscing about his fall from grace. It’s a story about how everything that you thought was good is actually bad, especially England, and you should be very sad indeed because all your old icons are built on lies and blood.

The final issue features the (heavily implied) anal violation of Dare by his old enemy the Mekon, who even gets the cheesy line, “Think of England, Colonel Dare.” It’s probably the most Mark Millar-esq thing Grant Morrison has ever written (and that includes the stuff he actually co-wrote with Millar). It’s all bleakness and misanthropy.

Look, it’s not as if I disagree with Morrison’s target bank, from the historical memory of England to its current (well, current to the ‘80s) politics, and it’s fascinating to see him express his emotions so clearly on the page. But he expresses his criticisms in such a straightforward manner it feels like it might as well have been a blog post. Or, given the period, an angry fanzine article. It keeps explaining why the old comics are bad, and you should feel bad for enjoying them. It’s one-note and one-dimensional in both character and presentation.

There are clever bits, mostly reserved to the final issue, but they are less related to the political posturing and more to Morrison’s usual meta-fictional interests: for example, as the story progresses, we are lead to believe that Dare’s memoir will serve the same role as Rorschach’s diary in Watchmen, showing the awful truth the powers-that-be has kept from the populace in order to preserve their bloody order. But in Dare, exposing the truth proves inconsequential. The people who learn of what happen are either afraid to speak up or have long since sold out. The populace, as a rule, does not care. Wicked people keep on being wicked and don’t even bother to hide it because they know their supporters do not care.

The other interesting touch is reserved to the end, in which Dan becomes an out-and-out terrorist by bombing the government with a hydrogen bomb. Not only is Morrison’s raw anger at Conservative politics felt far stronger here than in any other thing he’s ever written, a moment of “deeds, not words” that’s rare for a writer so obsessed with the influence of fiction over reality, the image of the bomb taking out everyone, fading into pure white before pulling back from that, revealing a drawing room with a blank page, is far more intriguing than anything seen before in the story.

Possibly, Morrison is just not right person to tell that type of angry story that was much in-demand at the time. I can’t fault Dare for its ideas, but the execution leaves much to be desired. An interview with Morrison published at the end of the first issue of the Fantagraphics reprint series has him noting that he sees parallels between his take on Dan Dare and that of Frank Hampton’s original strips, in that both show the character selling their good name in favor of some idealized notion of something that never actually existed. This is certainly more in Morrison’s usual ballpark, and it’s little wonder these parts of the series land with a little more impact.

Garth Ennis and Gary Erskine’s Dan Dare revival was originally produced for Virgin Comics, and if you do not remember this unfortunate venture (founded in 2006 as the comics arm of Richard Branson’s Virgin Group), I can attest to the fact that you are a human being. With titles such as John Woo's Seven Brothers (not actually written by John Woo) and Guy Ritchie's Gamekeeper (not actually written by Guy Ritchie), you can bet not much was lost when the company was renamed to Liquid Comics in 2008 and subsequently dropped off the map. The seven issue Dan Dare revival miniseries was the one true standout in the catalog. Thankfully, you don’t have to hunt through secondhand bins to read the story fully: the collected edition has been kept in print by Dynamite Comics.

This story belongs to a tiny subsection of Garth Ennis’s expanded bibliography: the revival of old war comics of which he was a fan of as a lad. Ennis’s experience with corporate intellectual property (more often than not, American superheroes) often involves him doing stuff he obviously doesn’t really want to do. One needs only to look at his work on Spider-man, Thor, and Ghost Rider (The Punisher being a special class that allowed him to indulge his usual proclivities even within a superhero setting). But every once in a while, he gets a shot at one of these old British characters, these square-jawed and morally unbent heroes of old, and we get to see a different side of Ennis – an almost child-like admiration for values long-forgotten of honor and decency. Such is the case with his Battler Britton, Johnny Red, and finally Dan Dare.

In his own war comics, the ideal of the old soldier, the one who dragged civilization from the brink of destruction by his sheer manliness, is something to look up to while acknowledging it never really existed. There are no out-and-out heroes in War Stories and Battlefields because these tales are meant to ape real life. To place cartoon figures in the real world is gouache (though, Ennis often surrenders to sentimentality; you can’t say he doesn’t try).

This Dan Dare is set as a sequel to the original. It takes place some unknown amount of time after the original adventures, with Dan retired from service and the Utopian world order collapsing (America is apparently an uninhabitable hellhole). Britain persists as a nation long ago surrendered to mediocrity. Writing this article with Brexit in mind, the story seems oddly prescient, not that I believe Boris Johnson is about to team up with an evil green alien to destroy the world via a portable black hole. (This would require a degree of competence that is not in evidence.) But this is a story about a country that renounces every Utopian ideal it might have had in favor of supposed realpolitik and ends up paying for it.

You can also see it as a commentary aimed at the modern democratic party establishment that keeps on pushing candidates that are “not good, but also not as bad as the other person.” People on the left giving-up before the fight even started, starting from compromised choices and moving onward. Of course, to accept that, you need to accept that Britain was once truly “great” in the way Ennis would like to see it. His Dare reminisces about World War II: “Small matter of saving the country, and western civilization along with it.”

It’s a rose-colored view of history, ignoring Britain’s own private theater of horrors abroad, but it works because Ennis and Erskine deal not in real history but in comic book history. They give us the Britain of the original Dan Dare, the country as it should’ve been after World War II and the foundation of the European Union. They ask, “How did we dare to let go of that dream?”

It’s surprisingly uplifting without surrendering to mawkishness, and like the 2000AD version, the creators grew up aware of the great fun to be found in the character. Their story moves along swiftly from set piece to set piece, from giant space battles, to daring marine raids, to ground battles, to “fix bayonets,” and everything else you might want from a war comic. Erskine’s storytelling is rather straightforward, missing the varnish offered by previous artists on the strip. But his Dare is note-perfect right – a square-jawed straight man who keeps his wits and honesty about him even as the world around him goes mad. Powerful, but never crossing the line into idealized ubermensche. A mighty man, but just a man. The series as a whole is an immediately sympathetic portrayal of an old man who still has a lot to offer, without becoming a lecture to stupid youths about worshiping previous generations.

It certainly feels more like an Ennis comic than a traditional Dare adventure. There’s a bigger focus on the action, and it portrays the space fleet as a straight-up military force rather a Star Trek-esq exploration navy, but it does so while respecting the educational notions of the original strip. It’s about what it means to be man, a soldier, and an Englishman.

Dan Dare, a 2017 miniseries from Titan Comics written by Peter Milligan, drawn by Alberto Foche, colored by Jordi Escuin Liorache, and lettered by Simon Bowland, is (as of this writing) the last new Dan Dare comic. It ends with a mandated “To be continued,” but seeing as nothing was announced in the last three years, I’m choosing to look at it as its own complete thing. On the face of it, this had the potential to be quite good. Milligan is one of the greats of the mid-80s British Invasion (though, his name offers less cache than that of Morrison and Alan Moore). When Milligan is on (Enigma, Human Target), he’s a superb writer, and he is a writer that can often be interesting even in his failures.

Therefore, it is quite sad to say that this series is not an interesting failure; it’s just a failure, period. It’s probably the single worst Dan Dare comic I have had a chance to read, and it’s a decent candidate for the lowest spot in Milligan’s bibliography. I wasn’t very familiar with the art team, but I was willing to be positively surprised. The retro-covers by Chris Weston, a great piece of promotional material, turned out to be nothing more than a tease.

The series starts with a commentary on the 2016 U.S. election and/or the then ongoing Brexit debacle, with Dan leading the resistance to dismantle the government of the recently democratically elected President Mekon. As it turns out, he used a sort of mind control machine to sway the public in his favor. And before you have a chance to groan, we are told, twice over in fact, that the machine wasn’t really doing mind control but simply ushering people’s darker impulses: “It’s been proven that the engine only effected some voters. Remember when women and minorities’ rights were eroded? The Mekon’s ratings shot up.”

Do you see? It wasn’t Russian interference or Cambridge Analytica’s fault – we were the real monsters all along! It’s true, of course. But it’s not exactly a revolutionary act of political commentary. Like the 1990 Dare series, this one is particularly unsubtle in hammering out its political point. Unlike Dare, it doesn’t have the spectacular pop-styling of Ryan Hughes, which at least gave the grim proceeding a degree of personality. Alberto Foche’s art is not bad per se. There’s nothing particularly awkward about his figure-work or action scenes, but it is uninspired to the extreme. This is what I imagine a Gold Key adaptation of a Dan Dare cartoon would look like – workmanlike all the way.

In issue #3, for example, our protagonists find themselves locked within a massive Treen ship and looking up they are meant to see “some kind of fourth dimensional architecture.” This blows their tiny human minds straight from the cranium. What the art ends up showing us is some big grey walls; it doesn’t even strive towards the uncanny. This is a comic book that acts as if it has the budget limitations of a 1970s science fiction show on the BBC (this includes a blue skinned alien lady).

It’s a story of fascinating ideas, at least in terms of radical approaches to an over-familiar concept, that remain undeveloped. The Mekon reforms (or does he?). The monk-ish Dan falls in love (with the above mentioned blue skinned space babe), and everyone in the world lives with knowledge that their neighbors voted for a vicious alien. All of these are introduced one after another and quickly swept aside. It’s a dull tale, preformed with all the excitement of washing the dishes.

There’s going to be more Dan Dare comics, and there’s even more we didn’t touch on because space is finite. Dan Dare’s name evokes too much for the notoriously nostalgic comics industry to give up on him. If anything, the fact that he’s been revived so many times just gives him more power – he’s not a character, he’s an icon (even if only on one small Island), an all-purpose symbol of that can be reshaped by the whims of the storytellers

It’s going to be a hell of a struggle to bring him back in an interesting fashion – he’s been revived, deconstructed, reconstructed, revamped, relaunched, altered and played as nostalgia. Finding a new angle is not going to be easy. But, as always, who dares wins.