Staging and Acting

I’m interested in what your goals are when you’re working on a story. There’s sometimes an outwardly straight-ahead quality to your narratives, but when you’re rendering out a page, what are your priorities? What are the main challenges, which you alluded to a bit earlier, that you’re setting up for yourself?

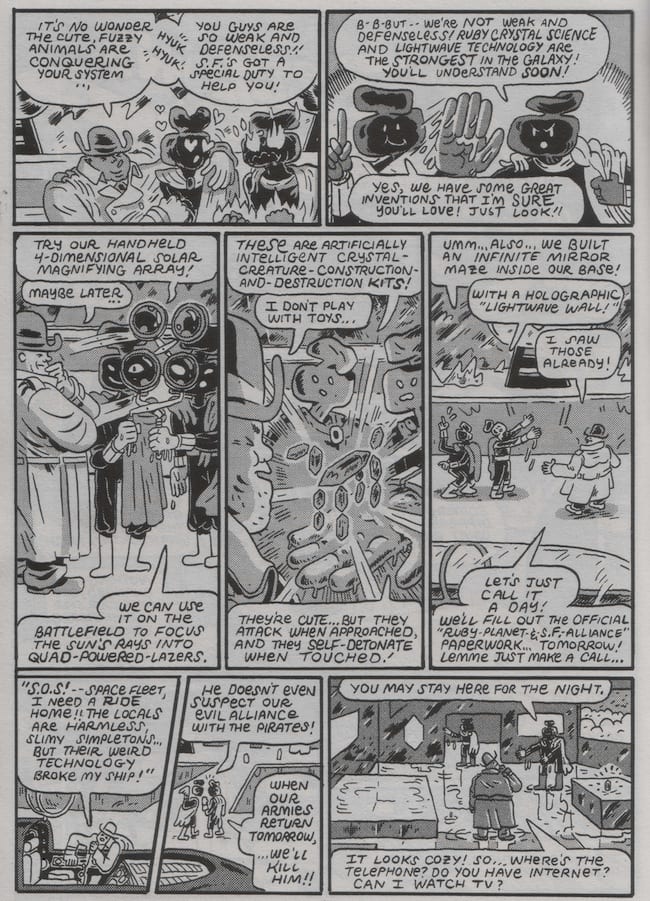

Well, I’d say that I’m not always successful at what I try to do, right? You know, but what I get into, I guess, is the sense of motion… I think when I did SF#2, I had a lot of pages that were rendered really tightly. And that was kind of because the environments were really hard to draw otherwise. Like, in a cave planet—that was like half the story. And I thought I over-rendered it at the time. I mean, to me, the rendering and having detail isn’t that important. I just get more excited by the flow and the rhythm from one panel to the next—like, moving things around and having beats. And then drawing backgrounds—drawing backgrounds is cool because it’s like giving a stage to everything. So drawing a “stage” is cool because it gives placement to the characters, and a place for all the things to happen. So rendering tight stuff isn’t something I’m necessarily excited about—but I think it’s necessary, because it gives something flavor, you know?

Yeah, I think so.

I don’t know—usually the exciting part for me is when I’m working out the thumbnails and working out the rhythm. I also keep a really tight grid in SF… well, not a really tight grid—but I use the same grid all the time. And I don’t know if I want to change that any time soon—I think I do really strong work when I do it. But there’s also times when I break out of it and it’s really fun. I’m just, I’m looking at SF#3 right now. I have it with me. Like, page 52 is off the grid, but I think it came out really good. I don’t know, I try to get a good flow and a good design and balance to all the pages with that “stage” in mind, and then I try to switch... I don’t know if this is what you want to hear.

[laughs] No, no, I want to hear however it is!

I don’t know, I try to switch and create a contrast between panels so that you’re not always getting the exact same kinds—try to make a rhythm between medium-shot-wide-shot kind of stuff, and where things are on the page. I guess technical comics stuff gets me really excited. Technical comics storytelling is something I think is really exciting. Drawing really cool stuff—like spaceships and outfits and glorious splash pages and stuff—that just isn’t very exciting. Making something look really cool isn’t my goal. It’s more about the technical stuff and the design; the technical storytelling, the general page design, the way things move on the page. And then making things look cool is maybe the least of my concerns.

Hm. Well, I can imagine how [Kazuo] Umezu would jump out at you, then. Because he’s another artist where clarity and flow are sort of the things he won’t compromise on at all.

Yeah, Umezu’s a really cool inspiration—and yeah, his stuff is, like—in terms of readability… I liked reading your stuff about The Floating Classroom [published in English as The Drifting Classroom]. The Floating Classroom is the first thing of his that I read, and he has a really amazing way to keep things going, because he uses the same… he does a weird thing with time, like, he’ll kind of keep focused on one character all the time. Like the main character in Floating Classroom, I don’t remember his name—but the little boy—

Uh, Sho, I think?

Sho, that sounds right. I think it might be Sho. But yeah, he’ll stay on Sho’s face, with Sho screaming at his mother, and then crying in fear. But then he’ll… you know, it’s goofy, but a page design is the way he’ll ground everything, like kids screaming and yelling. It’s kind of like stage acting. Always facing the viewer, you know? He always has the characters facing the viewer with a similar expression. Keeps it really readable, and it’s never too crazy. But the weird thing with time that he’ll do—like, really arbitrarily, it’ll be [a sequence of] really slowly watching someone’s hand grab someone’s ankle. Kind of like when Chris Ware does those stupid comics where he’ll follow the one mouse sitting in his chair again and again. And he’s tight on the one mouse going back and forth doing that. Umezu pretty much does the same thing. He keeps it tight on the character, on what the character does. And it’s very much like tracing their body motion as they do something. And if it’s dramatic to trace their body motion slower, he’ll just do that. But it somehow reads consistently. It doesn’t read like a crazy break in the page, because he is always just keeping on the character, and that grounds it. And that’s so cool—so straightforward, so readable, and yet it becomes kind of flexible, under the surface.

Yeah—I think it frees him up for all kinds of other experiments. The events of that comic get to be so all-over-the-place and bizarre because in a certain sense he’s so formally strict.

Yeah, totally.

Cross-Pollination

You said something earlier that I thought was interesting—which is that if you didn’t have Matsumoto to work off of, then SF wouldn’t have “a core.” Can you explain that a bit?

Well, I think SF is kind of this mix of Japanese sci-fi—like, older sci-fi from the ‘70s—and American sci-fi. And for me personally, I read a lot of sci-fi short stories and novels from the ‘40s and stuff like that when I was a kid. So I guess I’m more informed about Western sci-fi. But I don’t know if it’s “having a voice.” But I didn’t know how to approach making my own sci-fi stories that didn’t feel like just a rip off of Star Wars or Star Trek, or something. So for me, having another thing to bounce off of made me able to… like, I can do Star Wars gags. There are clear Star Wars gags in SF. I think there’s probably more Star Wars gags in SF than there are Matsumoto gags. But starting from a place that was totally different made me able to use those gags. If I wasn’t exposed to the Japanese world of comics, I wouldn’t have an interesting place to start from.

There’s a guy named Buichi Terasawa who does really Western-influenced, really Western-looking manga. And I love looking at that stuff, because it is very much like Western sci-fi. I just think even just a light cross-pollination for me helps a lot. I don’t think I’m super-deeply influenced by Matsumoto, but if I wasn’t influenced by him, if I didn’t read his books, I wouldn’t know how to do it. I wouldn’t know how to approach making a sci-fi story.

That’s interesting, because I definitely feel like the SF series, even though it’s called SF, and it has, say, a bunch of Star Wars gags, it doesn’t feel like “a tribute comic”—to Matsumoto, or to anything else.

Yeah, that’s a good point. SF is not a tribute comic. I mean, I think Two Eyes of the Beautiful is closer to that. I don’t know if I’ve told you this story, but I read this manga by Umezu, and it was amazing, but I couldn’t read Japanese. So I just guessed what the story was. And I think this is totally normal—but I just kind of guessed and kind of made up what it was about. And that’s what I turned into Two Eyes of the Beautiful #1. And it turned out to be pretty wrong. But then with #2 I took it in a different direction.

But it’s still very much an Umezu thing. You know, I put his name on the cover of the book. Because I don’t want anyone to think that I’m trying to take credit for it. Even though the stuff that’s mine is mine—but it comes directly from him. But Matsumoto’s comics… He has a really distinct mood to his work, which really affected me very strongly. And when I start from that—and also from Japanese culture, and Japanese lifestyle, and his comics—all of those affect me very strongly. And I think those give me a language to approach other stuff with. But it’s not about Matsumoto, it’s not exactly paying tribute to him. That’s not the point.

Well, I’m with you, and I don’t think it feels that way, but it’s a little … the reason for that is a little elusive to me. Like, why it feels different from something Brandon Graham might do, or, like, a Heavy Metal tribute.

Well, I think maybe a difference between SF and some other stuff is that part of my purpose is to introduce people to Matsumoto and to Umezu—that’s kind of why I want to put that [on the books]. People know what Moebius is, so if a contemporary artist does a Moebius thing, you kind of know what’s going on. Especially if you’re comics-literate. You can pick it up, and you can enjoy that very much. I was more concerned about this when I started, but people don’t [tend to] know anything about Matsumoto Leiji, or Umezu Kazuo? So I’m kind of trying to give people a lens into a different approach to world-building and attitude that’s possible in a sci-fi story. And that’s possible in life, you know? Like, different “life attitudes” in Japanese culture that make different sci-fi stories… that are really cool! So I kind of want to show that to people when they read it—maybe you’re not thinking, “Oh, this is a Matsumoto thing.” I don’t think that’s possible for most people. But maybe you can feel like, “Oh, this is different!”

Yeah. Okay.

But I don’t want to do a tribute to him, I don’t want to copy him. Because that wouldn’t be as fun for me. It’s fun for me to do a story and then show it to people.

Yeah. I can enjoy that kind of stuff, but as a reader I don’t always find it interesting, either. I think part of it is there’s a sort of reverence that’s assumed, or expected, that can get kind of irritating?

Okay, George… well, I could kind of go on a little bit about things I really like that inspires the work. And I don’t know how interesting that is for you, necessarily. But there are certain things that are really, really beautiful about living in Japan. Like, there’s a certain sincerity. Oh yeah! That’s a thing with Matsumoto: sincerity—that we don’t ever have in our literature. You know, like, even the antihero that he has. Is Harlock an antihero? I’m not sure. But he’s so full of conviction, and… I think we have a tendency to be more jokey in our culture. But I think it’s cool to have a world where everyone is totally serious. And it’s also less sexy? Like, sex is less a part of it. Like, for example—every actress in a movie… maybe Guillermo del Toro is a cool exception? Which I think people picked up on in that Godzilla movie [Pacific Rim] that he made? Usually in movies you have to have some “sexy heroine,” right? There has to be, always, sex appeal between the main actors. But in a lot of manga and in that Godzilla movie that he made, there’s not a lot of sex appeal. I mean, there’s appeal. They like each other. But it’s not about sex. And when you feel that difference, it’s refreshing! Because you’re like, “Oh, yeah! There doesn’t have to be that! I don’t want that in every story.” And, you know, relationships without that are cool! Ones without sex appeal are cool! And there are certain relationships that are like that in manga and that are like that in Japanese life where I’m, like, “Oh, man, it’s so nice.” When you have a certain kind of conviction or a certain kind of sincerity that you don’t see in our culture. And I’m like, “Oh, man—that’s the kind of story that I think people want to hear, and that I think people want to tell.” I mean, it’s kind of like breaking out of the clichés of art and literature, kind of? Which is all good stuff, you know, but it’s a different way to approach it.

Hm. Well, that point about sincerity is interesting, because all these elements—like, with your work, I don’t think the branding stuff is ironic. I don’t know if you saw that Sammy Harkham book, Everything Together, but it has these sorts of sayings on the covers. “Do You Believe in God?” or something. And it has the price. But those [design elements] feel a little more ironic.

Yeah. I don’t know where he’s coming from with those, but I noticed them too. And I’m not sure how to read them.

Yeah. ... I don’t really know either.

But I think people read my stuff and they don’t know how to read certain parts. Maybe. Because when I read Japanese stuff, and I see stuff like that, I’m like, “Oh yeah. I know what that’s about.” I think it’s probably the same thing, I’m not sure… it’s, um, “Do You Still Believe in God?” Right? [looking around the room] I have that book somewhere in here…

I think that’s right. [We’re both wrong, as you cans see above—but Ryan’s closer] [Laughs] It’s just an affecting question, I guess?

I don’t know. I will say, with SF#3, I put on the cover, “If you make a promise in space, you have to keep it or you die.” Which is the same kind of thing. And I feel like I didn’t work enough of that theme into the book. Which I feel bad about. I didn’t intend for it to just be a kind of interesting—or “ironically”—strong statement. And I should’ve worked that theme in more. I think as I was finishing the book, I couldn’t fit in part of the story as much as I wanted to. But I still think… Sammy Harkham’s… I wish we had that book in front of us. I think it’s a similar kind of thing. Because I think what I respond to—what makes me interested in those kind of captions— they’re real. I guess it feels kind of Kevin Huizenga-y too, but maybe that’s just because it’s a circle? I don’t know, maybe that’s just the circle stuff.

[laughs] Yeah, I don’t know.

Circle stuff… and also talk about God. It is Kevin Huizenga-y! But I think there’s also… and I think it comes from people who study, like [puts on severe, academic tone] “the essence of the word and image” [Elkind laughs] It’s kind of like [in same tone], “What is the exact meaning of this statement?” And I think there’s something about the directness of the statement, where the question is interesting. Like, what is the relationship of it to this other story? And it’s interesting. It’s hard to say, but I don’t think you have to know.

(continued)