Back at the dawn of webcomics, when it seemed like anything was possible and there would surely be more to the medium than strips about video games and stick figures getting mutilated, one of the popular buzzwords was interactivity. In Reinventing Comics, Scott McCloud speaks briefly, if none too enthusiastically, about the fleeting corporate passion for interactive comics on CD-ROM: “Voice actors were used to read word balloons out loud, some limited animation was offered, and readers were allowed to choose from short menus of plot twists.” Ultimately, McCloud notes, these usually uninspired projects “sidestepped the question of comics’ own evolution by letting comics become an undigested lump in multimedia’s stomach.”

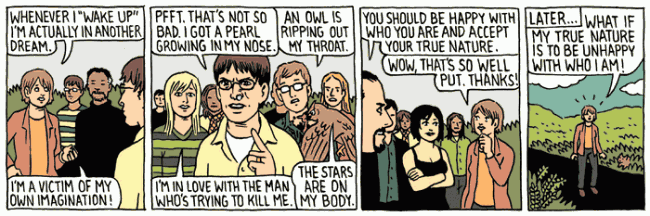

While CD-ROM publishers were trying to figure out how to turn Spider-Man into an immersive virtual experience, however, some webcomics were already using the interactive properties of the Web in more organic ways. In his comic Slow Wave, one of the earliest and longest-running webcomics, Jesse Reklaw came up with my all-time favorite comic concept: readers send in their dreams, which Reklaw illustrates as four-panel strips. Still running weekly after seventeen years, Slow Wave now has an ongoing plot of sorts, as a woman finds herself waking up into dream after dream. In a recent strip, a bevy of reader/dreamers confront her about her plight: “That’s not so bad. I’ve got a pearl growing in my nose.” “An owl is ripping out my throat.” “The stars are on my body.” Reklaw’s clean-line, comic-booky art lends an absurdly mundane quality to the bizarre subject matter.

This is the kind of interactivity that doesn’t require complex programming or flashy plug-ins, the kind every webcartoonist gets (or hopes to get), whether or not they choose to use it. The near instantaneous nature of online feedback makes it possible for a cartoonist to incorporate readers’ thoughts, ideas, complaints, and wishes into the comic as it runs. In retrospect, this type of mass collaboration was inevitable. After all, we use the Internet for a lot of things, but first and foremost for communication.

Hence the rapidly exploding popularity of Andrew Hussie’s MS Paint Adventures, in which the action from panel to panel is determined by reader suggestions. Initially a parody of Infocom text adventure games, MS Paint Adventures has mutated repeatedly, churning out two unfinished stories, “Jailbreak” and “Bardquest”, in which the narratives eventually disintegrate into pointlessness, before launching into the epic “Problem Sleuth”, which ran for a full year before reaching an ending. “Problem Sleuth” starts as a noir spoof, but, given the hairpin plot turns that come out of crowdsourcing a story, ultimately involves warring gods, Armageddon, Mandelbrot patterns, and lines like, “You retrieve the TECTRIX OF THE ARBITOR you were granted as a boon from the Weasel King a while ago to duel with Death. You had since stowed it in your HAT for safekeeping.”

Hussie’s art is, as the title of his site implies, not the most sophisticated, but as the comic has progressed he’s gotten gradually more ambitious, adding color, collage, animation, and even soundtracks to his wobbly stick-figure drawings. The current MS Paint story, “Homestuck”, continues this trend, and, unlike the previous stories, even has a preplanned story arc. This makes the interactive element less essential, and, as “Homestuck” has continued, MS Paint has drifted away from following reader directions at every turn and toward telling a story with only periodic nudges from the fan base.

MS Paint, along with the similar interactive fiction Ruby (archived here), has, like most successful webcomics, inspired numerous copycats. Most of them follow MS Paint’s panel-with-caption format and Infocom-esque writing style (complete with the sadistic, player-baiting sense of humor familiar to anyone who lost hair over Zork or Leather Goddesses of Phobos in the pre-graphics days of the Internet), even though many of the creators are probably too young to remember the source material. Many also try to follow Hussie’s impressive schedule; he often updates not just daily, but several times a day, as the Muse and the wisdom of crowds strike him.

Elsewhere in the vastness of the Web, cartoonists are still mining readers for personal stories, Slow Wave style. In A Little Death, for example, Donna Barr illustrates readers’ descriptions of how they imagine/fear/hope they will die. Some deaths are imaginative (chased off a cliff by a grizzly bear, eaten alive by a giant octopus, asphyxiation on the moon, “misadventure on horseback”), some mundane (coroner Hannibal wants to die “like Robert Shaw,” of a heart attack). Sometimes Barr’s adaptation provides an editorial slant: pirate radio engineer Juan imagines dying “of old age” “as the last man on earth,” so Barr draws him as the last man on a planet run by women, dying because “those bitches” won’t tend to his cold. And bootmaker Willis writes, “I’ve had cancer four times. I’ve beaten it every time. If it finally gets me, I’m really going to be pissed off.” Read together, and illustrated in Barr’s trademark sketchy-sexy penwork, they form a patchwork quilt that makes death look as rich and varied as life. Sadly, Barr put A Little Death on hiatus this past October; it’d be great to see her return to it in 2012.

Meanwhile, there’s Meanwhile. Taking a brief final detour to plug a non-reader-driven interactive comic, Jason Shiga’s choose-your-own-adventure opus, originally a print comic, is now available on iPad. Shiga has posted online versions of Meanwhile in the past, but the iPad version, engineered by legendary text adventure writer Andrew “Zarf” Plotkin, seamlessly transmutes the comic into an interactive ebook, making it the most readable edition of Meanwhile yet—and I own every edition save Shiga’s five-foot-square Meanwhile map, which is in Shiga’s house. Projects like the iPad Meanwhile suggest that maybe the dream of the ’90s is alive on the Internet after all, and this time comics won’t sit undigested in the gut of the new media.