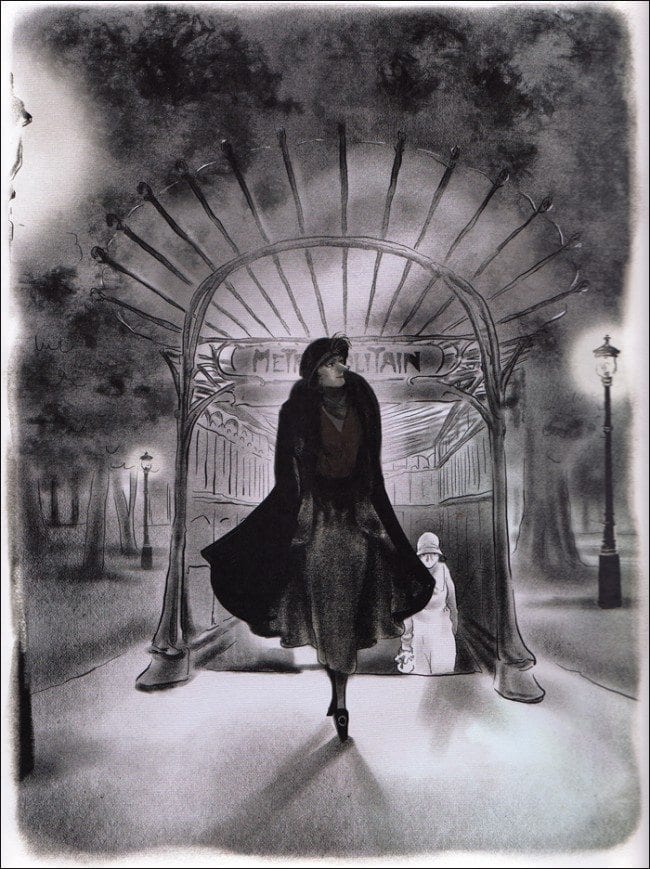

The cover of Chloé Cruchaudet’s Mauvais Genre ("Trashy Types") from Delcourt makes you think it's a story about stylish lesbians. Yet the French bestseller – which won both the critics' Prix ABCD and last year's Angloulême's Prix du Public – takes place during and just after World War I. The couple on its cover are in fact working-class Parisians, Louise Landy and Paul Grappe, whose strange story is actually true.

The cover of Chloé Cruchaudet’s Mauvais Genre ("Trashy Types") from Delcourt makes you think it's a story about stylish lesbians. Yet the French bestseller – which won both the critics' Prix ABCD and last year's Angloulême's Prix du Public – takes place during and just after World War I. The couple on its cover are in fact working-class Parisians, Louise Landy and Paul Grappe, whose strange story is actually true.

Married to Louise on the eve of World War I, Paul was a draftee who deserted the ranks. He spent ten years hiding in plain sight – by living with Louise as a woman called "Suzanne Landgard". Less constrained than freed by his female identity, Paul took to cruising after dark in the Bois de Boulogne. (Eventually he also pimped his wife to other park habitués). In 1925, when the French offered deserters an amnesty, "Suzanne" dumped the dresses and returned to a life as Paul.

The couple's new normalcy, however, proved to be troubled. When Paul's sex swap brought him a modest notoriety, the attention only worsened his bad temper and drinking. Their saga ended badly when Louise shot and killed him. Yet, re-positioned by her lawyer as a battered wife, 'Madame Grappe' was fully acquitted of the murder.

Cruchaudet found Paul and Louise in a book by two historians (La Garçonne et l'Assassin by Danièle Voldman and Fabrice Virgili). But she turns this item from the police blotter into a showpiece. Paul and Louise are only "little people of Paris", a pair who struggle every week with paying rent and buying groceries. Cruchaudet, however, brings their tale both grit and romance. Her couple is not so sympathetic but they're funny and fascinating – and her pages burst with an irresistible panache.

Under pressures they never expected – first terror and violence at the Front, then a clandestine life – Paul and Louise stick together and cope with every change. The biggest, their reversal of roles, comes about by chance. Stuck in their tiny flat all day while Louise is working, Paul starts going stir crazy. Late one night, desperate for a bottle, he visits a bar in drag.

Under pressures they never expected – first terror and violence at the Front, then a clandestine life – Paul and Louise stick together and cope with every change. The biggest, their reversal of roles, comes about by chance. Stuck in their tiny flat all day while Louise is working, Paul starts going stir crazy. Late one night, desperate for a bottle, he visits a bar in drag.

A liberating idea is born: maybe he can pass for a woman! Frightened for his safety, Louise starts to school her husband. Carefully, she instils the manners and looks he needs to seem female.

It all begins in giggles that spring from the tensions of underground life. But, slowly, things start to take a serious turn. The pair can't manage to feed themselves on a single salary. So Paul, as Suzanne, decides to join his wife at work. Poor Louise has longed to escape her textile sweatshop. But, for her better half, it offers a psychic reprieve. As "Suzy", he can relax: chatting up pretty seamstresses, mocking the foreman and participating in the workplace gossip. Even the silky fabrics they slave over start to please him.

Does his role-playing exert a force of its own? Or has Suzanne been a part of Paul all along? Certainly he is a woman ready to change with changing times, while Louise remains obsessed by pre-War hopes and dreams. (At one point, shocked by his wife's lack of attention to fashion, Paul insists on bobbing her curly hair).

Neighbours and workmates take Suzanne and Louise for a lesbian couple, yet even the building's nosy concierge accepts them. But one night Suzanne finds herself in the Bois de Boulogne, where she stumbles into its other life as a sexual playground. Paul's evolving tastes make Suzy a star in this cosmos. When a lonely, jealous Louise finally tags along, she is also – to her surprise – attracted.

Cruchaudet's Paul spends only a dozen pages at war. Yet these images, in stark black and sickly green, explain all the dislocations that come after. Paul and his friends think going to war will enhance their virility. But the filth and atrocities annihilate Paul's sense of self. As he is trying to save his old friend Marcel, for instance, Marcel's head is abruptly blown away. When its bloody stump insists on still "speaking" to him, Paul cracks completely. Desperate to get away from the Front, he cuts off a finger.

Although he escapes the hospital and goes into hiding, Paul's hallucinations – including the dead Marcel – persist. He tries to distract himself in the netherworld of the Bois. But once the pretty Louise joins in, even that universe fails him. As with those troops at the Front, its actors are merely bodies; just like the soldiers, every one is replaceable. Both Paul and Louise see this, yet neither wants to accept it. They’ve come too far from "normal" life to give up its thrills.

Although he escapes the hospital and goes into hiding, Paul's hallucinations – including the dead Marcel – persist. He tries to distract himself in the netherworld of the Bois. But once the pretty Louise joins in, even that universe fails him. As with those troops at the Front, its actors are merely bodies; just like the soldiers, every one is replaceable. Both Paul and Louise see this, yet neither wants to accept it. They’ve come too far from "normal" life to give up its thrills.

Cruchaudet does an impressive job presenting the Bois de Boulogne. Under her hand, its kinky games appear as dreamlike and comic. Envisioning this and the Front, she says, were her book's biggest challenges. "Partly because, in all my research, there were no concrete details. Nothing really told me how Paul's wife reacted – or what either one of them actually thought of as sexual liberty."

She has always been an artist who excels at storytelling. Cruchaudet's first bande dessinée, Groënland–Manhattan, concerns another forgotten slice of the fin-de-siècle. Published in 2008, it is about Minik Wallace, an Inuit baby who was brought to New York from the Arctic by Robert Peary. Prized as the explorer's trophy, Minik is raised in America – where he ends up losing both his family and dignity. Its narrative won Angoulême's prestigious Prix René Goscinny.

That choice was validated just a year later, when Cruchaudet launched a three-volume series, Ida. Ida is about the transformation of two hoop-skirted travellers, Frenchwomen who set out for Africa during the 1880s. Like all the artist’s work, it is quirky, inventive and preoccupied with what comprises human identity.

In Mauvais Genre, Cruchaudet's art has developed enormously. Based around a palette dominated by smouldering greys, the story is distinguished by an ingenious use of red. Whether applied to blushes or skirts, smiles or a scarf, red becomes our indicator of the feminine. When applied to the "normal" – a young Louise or the callow soldiers – it can seem as common as a glass of tomato juice. But as Suzy comes into her own, it morphs into a flagrant crimson. Only at the end, as blood, does the colour return to Louise.

The use of red is just part of Cruchaudet's attention to rhythm. Her images and their memories dance, floating through or circling around the album's pages and distorting the frames. The further her protagonists drift from social norms, as well, the sharper and darker their features start to become.

The use of red is just part of Cruchaudet's attention to rhythm. Her images and their memories dance, floating through or circling around the album's pages and distorting the frames. The further her protagonists drift from social norms, as well, the sharper and darker their features start to become.

In Europe's commemoration of the World War I centennial, bandes dessinées and graphic novels play a serious role. Numerous exhibitions and memorials are featuring them – from Tardi’s classics to 2009's Scars of War. Even the Paris métro joined in, turning Joe Sacco's The Great War into a monster mural.

Mauvais Genre offers a tribute with few parallels. After all, the unlikely tale's third character is the War. Not only does that conflict force the drama's choices and sufferings; it re-shapes the social expectations around Paul and Louise. Their immersion in debauchery is – like so much life in the Twenties – partly an attempt to try and loosen its hold.

Cruchaudet has added several surprising twists to the story. But, for her, historical veracity was never the aim. "With true stories, there are facts that simply wouldn't work on a page. The real Paul, for instance, was one of the first 'women' to try and make a parachute jump! In addition to everything else, that would never have been believable. There are always things you have to leave behind."

"To make a fiction communicate, you never choose the typical elements. You want to seize on the oddest, the most surprising things. In history, I find those. I find the sorts of details I could never, ever imagine."