Every now and then, when a new publishing concern pops up, one wonders how it's possible they weren't there all along. Some publishers fill a niche that one didn't even know existed, and as a reader you're the richer for having been exposed to it. Sparkplug Comic Books, PictureBox, and Secret Acres are three American companies that immediately come to mind, though all three were obviously strongly influenced by the aesthetic (if not economic) model blazed by Tom Devlin's Highwater Books. Koyama Press has a similar role in Canada. Both of these countries have strong alt-cartooning traditions. England is a country that historically has seemed way behind the US, Canada, and Europe in terms of publishing and appreciating art comics, but two burgeoning publishing concerns are filling that gap. Nobrow Press and Blank Slate Books bear little resemblance to each other in terms of design and aesthetic focus, but both are playing a role in not only providing a place for young British artists to publish their work, but also in bringing the work of European artists to English-speaking audiences for the first time.

If Blank Slate has a U.S. analogue, it might be Top Shelf. The emphasis here is on narrative and character above all else. The design of the books is simple and clear, but not especially spectacular. Three of the four books I was sent deal with autobio variations and the fourth is historical fiction. In that respect, these books differ a bit from Top Shelf in that they eschew most genre conventions. Let's take a quick look at each of them in turn:

The Accidental Salad, by Joe Decie. This is my favorite of Blank Slate's offerings. Decie uses a muted, restrained black & white wash to uncork quirky and fanciful autobiographical musings. This forty-page comic reminds me quite a bit of Lewis Trondheim's autobio work, in that it is not so much directly confessional but rather displays the machinations of the artist to turn himself into a droll punchline. As in Approximate Continuum Comics, Decie starts a narrative anecdote in an expected manner, then quickly moves into absurd territory, all in a deadpan style. The strip where he talks about how he does his comics is a great example, wherein he discusses spreading coriander seeds around his scanner so that the demons who haunt those devices will be distracted by having something to count. Decie manages to mine humor from his wife and young son in a similar fashion, though those strips tend to be closer to pure naturalism than the flights of fancy that take place strictly in his own head. All told, this was one of the best autobio comics I read in 2011. The format of this comic is much like that of the Ignatz line: heavy paper, subdued colors on the cover, and a dust-jacket style cover with french flaps. It's both beautiful and familiar.

Luchadoras, by Peggy Adam. This is an odd book that addresses the misogynistic violence taking place in Juarez, Mexico through the experiences of a single fictional character and the people she meets. Adam's line is crude but powerful, packed with a considerable emotional charge but also buffered by restraint. It's a polemic disguised as a narrative, one in which all of the men in Juarez (and some of the women) are complicit in crimes against women. The result is unrelentingly grim, and even if it feels like Adam is stacking the deck narratively by piling on misery after misery on her characters, the protagonist of the book manages to live through the experience. In some ways, the ending Adam comes up with is far more crushing than if the character of Alma had died. The foreign man who comes to her rescue in some respects is a stand-in for the reader, wanting to rescue Alma from her horrible life. Instead, he betrays her as well, killing off the last vestige of hope and idealism she possesses. The insights the book offers are not especially novel, but that's part of the point: the book is an invective at the very idea that this tragedy even exists in a supposedly modern society.

The Band, by Mawil. The artist is a German autobio cartoonist whose rambling style is very much in the vein of Jeffrey Brown and the wave of Swedish autobio cartoonists from the last decade or so. Mawil lived on the other side of the Iron Curtain and was just thirteen when the Berlin Wall fell. That must have been an incredible time for a young person to transition from childhood to burgeoning adulthood, as literally anything must have felt possible and the typical self-mythologizing that comes along with being a teen must have risen to epic heights with the promise of the West available at last. The Band is a sort of more gleeful companion piece to Gipi's Garage Band, one without the emotional resonance of that latter work but still packed to the gills with energetic cartooning. His line is a bit like Manu Larcenet's: loose, busy, and rubbery. Cartoony characters jam each panel with all sorts of action for the eye to follow. This book feels a bit overstuffed at eighty pages, especially for a book that's so episodic in nature, following the misadventures of the various bands Mawil particpated in.

Home and Away, by Mawil. This collection of strips is a better gauge of the artist's strengths. None of what he discusses here is exactly innovative in the world of autobio strips, but it's attractive and funny. His line holds color well, and the strips about his particular love for a video game demo, the relationship he had with his first junker of a car and how he discovered a love for graffiti are some of the strongest in this collection. That said, "Welcome Home", a long story about his attempts to get laid at a hippie gathering in France, score huge points for the absurdity of the event and his own series of humiliations. I can understand why these books are so popular in Germany, because the propulsive nature of his line and his willingness to portray himself as an occasional buffoon make this comic compulsively readable. His work is nowhere near as clever as Decie's, but his heart-on-his-sleeve (with a joker waiting inside) approach immediately puts the reader on his side. This is mainstream work in the true sense of the word.

I don't think it's an accident that Nobrow's books are distributed by AdHouse at U.S. comics shows, because the design and illustration emphasis of the English publisher is one that's sympathetic to the company run by graphic designer Chris Pitzer. It's an aesthetic that's part Drawn & Quarterly and part Blab!, where design and color are often more important than line and narrative. This is not to say that narrative is irrelevant in these comics, only that the narrative direction is more on the abstruse side. The design, packaging, and attention to detail and color here are almost painfully exquisite. That's true even in their "17x23" series, which are 24-page comics "designed to help talented young graphic novelists tell their stories in a manageable and affordable format." Nobrow also sells handmade books, prints, toys, and even wrapping paper, all with the same bold and colorful design sense. Their Nobrow anthology is an illustration spotlight, though the most recent volume (#7) also has comics content. Here's a quick survey of the bounty I was sent:

Hildafolk, by Luke Pearson. The 23x17 books are about the size of an issue of Papercutter, only in full color and with French flaps. This book aimed at kids follows the adventures of a girl who lives on a mountain and looks a bit like a Jordan Crane comic, only with characters that are drawn more roundly and with stick-arms like Leslie Stein might draw. This book is an absolute delight, as the scrappy Hilda encounters a troll, deals with a man made out of wood who won't stay out of her house and winds up with a pet that's part fox, part reindeer. Pearson works mostly with pastels, which helps emphasize his line thanks to the overall soft feeling of its colors. Browns, blue-greens, russets, and sea-greens dominate the color scheme, creating a comic that's warm and inviting to the reader. His sense of humor and ability to create a bit of suspense in his stories is very similar to Crane's, whose children's books have the edge that all the great ones possess. Pearson is very much in that category as well.

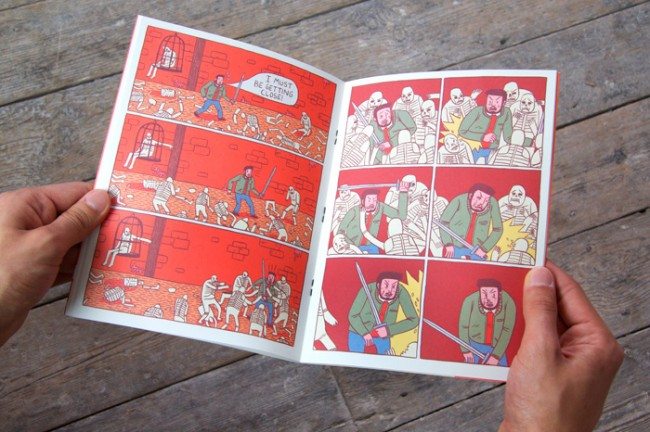

Jeff Job Hunter, by Jack Teagle. This is one of the more narratively straightforward of the Nobrow books, as Teagle combines sword & sorcery fantasy work with absurd humor. Teagle's line is reminiscent of Alec Longstreth's in terms of its boldness, simplicity, and static nature; the panel to panel transitions are all a bit stiff. This comic is strictly a lark and would have looked fine in black & white, and the end result feels a little insubstantial in terms of content matching form.

Ouroboros, by Ben Newman. This is a simplistic but graphically interesting comic dominated by loud greens, reds, and mixtures of the two, as an anthropomorphic rabbit finds a new set of eyes when he happens upon a corpse and winds up being captured by monstrous aliens. This is a kinetic, fluid book whose ending is deliberately telegraphed but still fun to reach. It's less a comic than a sort of graphic exercise for the cartoonist, one that's interesting to scan but ultimately less compelling than some of the other Nobrow comics.

Temporama, by Clayton Jr. This comic was the most visually striking of the bunch, as the narrative is almost entirely carried by moody, noir-ish color. It's a silent story about a man who goes out late at night to get some food, only to be chased by a man in a sort of monstrous piece of construction equipment. It's one of the more interesting depictions of night in the city that I've ever seen in comics form, as the Brazilian artist uses a midnight blue as his base color and juxtaposes it against the extremely harsh and bright yellow of a store and the bright reds and purples of a fireworks display. Clayton Jr. makes that darkness work for him, keeping the story bouncing along à la Carl Barks despite the fact that he's not using a standard line to keep the reader's eye moving from panel to panel. Like many of the other 23x17 books, this comic is slight of story but fascinating to read.

Birchfield Close and Pebble Island, by Jon McNaught. These small hardback books have the feel of the Petits Livres series from D&Q or perhaps a poetry chapbook found at your local independent bookstore. McNaught's work is like Tom Gauld if Gauld used an intense, almost pointillist style of coloring that dominated his strips. McNaught's comics feature no dialogue and are dominated much more by landscape than figure; like Gauld, his figures are a tiny part of their environment. Pebble Island is about life in an island community where isolation and boredom are dealt with in different ways. In one story, a boy goes through an elaborate, painstaking series of rituals just so he can blow up a toy with his friends in an abandoned bog. In another, a man comes face-to-face with his isolation when his generator runs low in the middle of watching Raiders Of The Lost Ark, only to resume his escape into that most escapist of films when he fixes it.

Birchfield Close takes the opposite approach, as it examines life in a jam-packed suburb where every house looks the same. Two boys spend an afternoon taking great pains to make it up to the roof of a house where they can watch others, and they gaze silently at their subdivision settling down after sunset and coming to a "close." McNaught's take on claustrophobia and alienation is just as interesting as his take on isolation and loneliness; in his view, both states are simply the flip side of the other. Corals, light pinks, and blues dominate his color scheme, which makes sense since these hues ably represent the dying of sunlight. I can't imagine an artist's content matching the format of the books their stories are printed in any more appropriately than McNaught's work for Nobrow.

Dogcrime, by Blexbolex. This French artist had a story in Kramer's Ergot #7, and it's easy to understand why his unique graphic approach would appeal to Sammy Harkham. Blexbolex's figures are colorformed shapes, sort of like the shapes Richard McGuire uses in P+O. He accompanies these frequently dense, melting images with crazy narrative text about a private detective who is framed for an unspeakable "dogcrime," an act of violence that compels an entire city to form a lynch mob. Though he's able to track down those responsible, Blexbolex gives us an ending that's amusingly apocalyptic and bizarre. Printing this short story as essentially a deluxe minicomic fills exactly the sort of niche that Nobrow serves, because I can't imagine any other publisher trying this. That's too bad, because this is a great comic by a unique creator, one of many European cartoonists whose work many English speakers have never encountered.

![graphcos_slide06[1]](https://the-comics-journal.sfo3.digitaloceanspaces.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/graphcos_slide061-650x432.jpg)

A Graphic Cosmogony, edited by Alex Spiro. This is Nobrow's visually stunning anthology wherein each artist gets seven pages to give their version of the creation myth. Without exception, each story is beautiful, bold, and distinctive. The narrow directive of the anthology does mean that certain themes and plot lines are repeated: the universe created as a kind of game by a bored god, for example. The best of these is Lucas Melanson's "Deus Magicus", which reimagines each of the biblical days of creation as part of a magician's stage act; this strip is made effective by the sharp yellows and blues. There are also some more traditional takes from various mythological systems, like Mikkel Sommers' adaptation of Norse mythology in colors that are bright but not cheerful, or Daniel Locke's more primitivist approach to the Ainu of Japan.

![graphcos_slide08[1]](https://the-comics-journal.sfo3.digitaloceanspaces.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/graphcos_slide081-650x432.jpg)

Jon McNaught's "Pilgrims" may be the best piece in the book, depicting the creation myth of Christianity as told through stained glass to a group of pilgrims. This silent story is so effective because McNaught effectively balances the awe of the meaning of the images the pilgrims see with the distance and alienation foisted on them by the physical environs of the church itself. He's also quick to note how the experience is in many respects simply an opportunity for commercial exchange and how quickly many of the pilgrims are to buy things. Other highlights include Isabelle Greenberg's "Masters of the Universe" (a creation tale about a father and two children that's a bit reminiscent of Theo Ellsworth's art) and Stuart Kolakovic's "Illumination", a blocky and cartoonish account of how a monk's fever dream wound up branding him a heretic.

While it's obvious that both Blank Slate and Nobrow have a steadfast commitment to quality and producing beautiful books, it's worth noting that these are still young publishing concerns. As such, they have yet to publish a book that's in the same strata of quality as the best of D&Q or Fantagraphics. Part of that is a function of time; D&Q in particular nurtures the artists in its stable and allows them to grow. The new British presses don't have the advantage of a Chester Brown or Seth publishing with them for nearly twenty years. I get the sense that this is something that is understood by the publishers, who don't push graphic novels as much as they do shorter works. It will take time to develop talent, but it's obvious there are a number of artists here (Pearson, McNaught, and Decie in particular) who are brimming with talent and potential.