One day, I will be as dead as Jack T. Chick.

* * *

I was extremely religious as a child. When I'd kneel down to pray at night, I'd set up small icons of Jesus and Mary on my bed and I'd get out a little prayer book from which I would perform readings. I'd been an altar boy, so I was used to navigating the great index of lore that tottered atop the lectern; I'd read all the books available in church, in fact – everything, even the stuff nobody read aloud. In the missalette, for example, there was instructions for what should happen if chance or misfortune conspired to present a non-Catholic at the celebration of the Eucharist. They could not receive the body and blood of Christ – not even other Christians were allowed such communion, and that made me proud; I felt like I was born into some elite number, starting at the top. And I wanted to keep it that way.

So I tried to make everything perfect in my nightly masses.

And then -- not every night, but on most nights -- I would lay down and I would beg God to kill me and destroy the world.

Such was my early affinity with comic books.

In Fun Home, Alison Bechdel writes of a certain childhood preoccupation, by which she believed that upon crossing some invisible line, say, or moving her body in the wrong direction, she would somehow cause a catastrophe. I was exactly the same way, but there was a religious aspect too, as with Justin Green in another, earlier autobiographical comics landmark, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. His anxieties were sexual though, while Bechdel's and mine were not. I suppose I've always preferred violence to sex, when it doesn't involve me.

The lifelong atheists among you may not fully ascertain what I'm about to reveal, but I beg of you nonetheless to surrender to a child's imagination. “Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven,” Matthew 18:3. I was maybe 9 or 10, and I couldn't picture God as a person. He made me in his own image, I knew, but He was also simultaneously a bird and a ghost, so it seemed to make sense that He could also gaze through innumerable astral faces, feeding a massive fungal brain processing anything and everything at once, which is how He has heard every prayer and knew every deed – to claim that it was narcissism to insist that God heard your prayers and not those of the starving and maimed revealed only a saddening paucity of imagination, which I attributed to lack of faith. Because I had faith, I knew that God would receive my petition for mayhem, and could easily, with a stray thought, act on that.

My weakness at that time is now self-evident: I could not understand how any worldview beyond my own could possibly survive as valid. Deviations were mistakes; shortcomings. 'B' grades to my 'A'. God was real, so real and strong. I'd heard all the Catholic kid stories about the guy who thought -- merely thought! -- that he'd like to die, and God gave him a heart attack right there. So I felt compelled, in the face of this immense power, to ask God to kill me. To kill everyone. Kill my parents. Kill my friends. To cause all of us to blink from existence, forever.

And then I'd plead with God:

Please don't let anything happen.

Please don't let anything happen.

Please don't let anything happen.

Ten, twenty, forty minutes. It was so pleasurable, this negotiation with Armageddon. Maybe it was sexual; fetishistic. Onan, unwilling to consummate his divine agreement.

* * *

There are several ways in which Jack T. Chick demonstrates his affinity with comic books, but initially I think it's important to recognize a man with the foresight to give things away for free.

We've all heard of Chick tracts – those little rectangular comic books people buy in bulk, and then scatter around public places as a means of witnessing the Gospel of Christ. It was around the same age as my protestations of cataclysm that I found my first such item. I was with my dad and my younger brother at a Domino's Pizza, and sitting on a bench was a tract titled The Sissy?

I think my brother was the one who found it. It was a comic with trucks in it, and he really liked trucks and backhoes and stuff. I know now that this was an unusually desirable tract, because it was drawn by Fred Carter: the Good Chick Artist. Like Carl Barks, nobody knew his name for a long time; Chick himself was an industrial artist a little earlier in life, doubtlessly acclimated to the studio procedures of Walt Disney and etc., which countenanced no compelling need to identify individual contributors. Still, Chick's own '50s-ish magazine gag look could not be more different from Carter's detailed muscularity, entirely self-taught with a prodigious gift for caricature of puffy, beefy faces; Corbenesque.

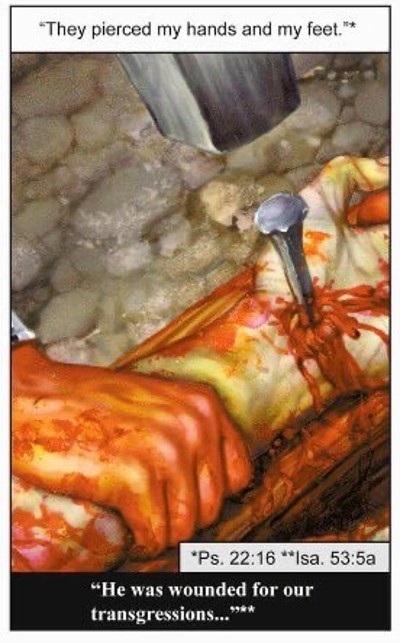

The story of The Sissy? is pretty much built for Fred Carter; it's about these two grizzled truckers, one of 'em in a huge-ass hat, who talk about tough stuff like throwing dudes through windows and shit. And then one of them sees a Jesus Saves sticker on another truck and he goes “Jesus was a sissy!” And then a booming voice goes I HEARD WHAT YOU SAID and this gigantic seven-foot-four motherfucker walks out and the guys are like GULP! but all he does is sit them down inside a diner and tell 'em how tough Jesus was. How he had all the power of God, but chose to forgive. How he endured his muscles ripping open in the scourging and iron nails pounding through his hands: real The Passion of the Christ stuff, and let me tell you, if you were a kid growing up Catholic and you had a nun for a teacher in second grade who kept this Spanish painting of Jesus under the glass top of her desk, this blood-spackled Christ covered in yawning crimson wounds, soaking the flimsy cloak they'd rip sticking from his body on Calvary, and if that scared the fucking shit out of you, and set you on the path of transfixion with the aesthetics of gore, friend - the success of that film was no surprise.

Anyway, my brother and I were completely tickled by this comic. Of course, the big guy saves everyone (in the evangelical sense), and they all bow their heads and pray at the table and this cliché cook with a white hat peers out the kitchen window going IS THAT A PRAYER MEETING I SEE? It was really funny, and we immediately liked this man we'd eventually, imperfectly come to know as Jack Chick.

But there were two subsequent comics that would cause trouble.

* * *

The first problematic comic was titled Gun Slinger (1997), which I would read in high school. Chick drew this one himself. It was all about a swarthy, unshaven outlaw who rides into town with a malicious task; all the classic cartoon stereotyping is out in force to code this guy as BAD, black hat and all. He's a killer and a varmint, and the virtuous white hat Marshall is out there to put him away and save the town, and that's basically what he does.

But before the outlaw gets rounded up, this preacher he's been hired to kill talks to him about being saved, and about being born again and accepting Christ as your personal savior - and the outlaw wants to be forgiven his transgressions. And so he goes to the gallows accepting God.

And the Marshall is a very righteous man, but he's not accepted Christ. And while he's riding out into the desert, a rattlesnake leaps out from the sand and bites him, and demons appear to drag him into hell, and he protests that he's a good person and it doesn't fucking matter. Being a good fucking person and respecting people and being nice and doing good fucking deeds does not fucking matter. In fact, you know what you deserve for your empathy?

Eternal fucking torture. The worst, most agonizing pain imaginable, suffering beyond human comprehension, until the end of time. You deserve exactly the same punishment as a murderer. You deserve exactly the same punishment as a rapist. Because all of us, fundamentally, are garbage, and the only means of knowing salvation is through accepting God.

You know who loves empathy? Satan. You know who loves altruism? Satan. You know who rules the world? Satan rules the world, and anything functioning in this world is thereby under his command, and there is only one way, ONE WAY to transcend your programming.

This, in less dramatic terms, is the essential divorce between Catholic and Protestant ideology. Put simply, the Catholic view is that God's efficacious Grace is accessed through through sacramental means, and, moreover, can be augmented, replenished, *enhanced* by the performance of works. Grace, however, to Luther -- opposing the Church's abuses of its self-declared position as arbiters of salvation, selling indulgences like money-changers in the temple -- was solely the province of God, and could only be accessed via faith in Him. You are a little thing, a broken toy, and you cannot fix yourself.

But you can be fixed.

* * *

The second problematic comic I cannot fully identify. It was another one my brother found, this time while we were on a family vacation. I feel a shiver when I hear the title Why is Mary Crying?, so I think it was that. Definitely it was one of the heavy anti-Catholic pieces Chick would intermittently release to illustrate the points I've just raised. Positing veneration of the Blessed Virgin as a stratagem of Hell was one provocation too much for my mother, who ripped that tract up not unlike the irate non-believers in Chick's actual comics; the only other thing I recall clearly is my brother wailing that the comics are funny.

Criticisms of Chick have historically proceeded in much the same way. Some become irate; some see only humor. The most clichéd reactions combine both, building a simmer of mocking comedy up to a boil of moral indignation. The comics scene, however, was early in advocating another way. In 1979, cat yronwode wrote an essay for The Comics Journal #50 titled “Blackhawks for Christ” - a broad overview of The Crusaders, which was a series of comics Jack Chick and Fred Carter had begun releasing in '74, starring idealized, young, muscular versions of themselves. These were not tracts, but full-sized color comic books, which you'd have to go to a store and buy. Carter drew them all, but nobody knew who he was back then.

The Crusaders hung around until 2016, still drawn by Carter, but mostly as a venue for comics adaptations of personal religious testimony or prose works from outside the Chick operation; back then it was a proper adventure comic in which 'Jim' and 'Tim' would smuggle Bibles into commie territory or tangle with cultists in between bouts of biblical-historical exposition, and what yronwode suggested was that you could read these comics not as blunt tools of conversion but as world-building: as comics possessing an internal logic (or compelling illogic) of the sort you'd see in the long-lived war comic Blackhawk. Even if you see war as an atrocity, you can still enjoy Blackhawk, in that you can consider the aesthetics of the work – a option which yronwode, writing from a time when the question of whether comics could or should be 'art' was still very much open, positions as necessary for any legitimate art form.

Today there is no controversy as to whether comics are art, and I think Chick always knew it, because his practice had a very particular objective.

What comes to mind immediately is a 64-page comic Chick & Carter produced in 1980, a one-shot apart from The Crusaders, titled King of Kings. It's a Greatest Hits version of the Old and New Testaments, drawn with Carter's autodidactic aplomb. All the most dramatic and visually acute portions are devoted to evil. Jesus Christ does not receive a splash page in this book, but Lucifer does, staring glamorously out into the distance anticipating the sympathies of the Vertigo label. Another splash depicts the mighty obliteration of the Pharaoh's armies in the Red Sea, and before that sits the obliteration of Sodom: big, strapping men, nude above the waist, posing and gesticulating, arms wrapped behind their heads in exquisite agony. A huge cobra rips through the earth, flames spewing everywhere, while a phallic obelisk, like the Washington Monument, pregnant with Masonic and occultist significance, topples. In the foreground is a very effeminate, very camp Sodomite in lovingly-detailed green eye shadow, shrieking in terror.

And the caption reads: “Right after that, the city was wiped out with fire and brimstone from heaven. Only three people made it out to safety. (A picture of the U.S. in the future?) It is estimated that over 10% of our population are homosexuals... and proud of it! God help us!”

One can, of course, adopt the poise of apologia. That Chick and Carter vivify rather simple Biblical scenes so fiercely, is to reveal the hidden rot beneath the piety of faith. The Bible, a genocidal text, is simple to apprehend as such from the gristle inherent to Fred Carter's depictions of flood and plague. So too it goes for Chick's taste for counter-intuitive argumentation. Good men deserve eternal suffering? The prosecution rests – no more evidence is necessary to demonstrate the toxicity of this favored draught.

Elsewhere in King of Kings, comparisons are drawn between Biblical events and then-contemporary politics. A gathering of peoples in Babylon is deemed “the first United Nations.” This is more than a bit John Birch -- as is the conspiratorial dint Chick pressed on the activities of Jesuits, Communists, Satanists, etc. -- and to the rightly distanced and/or contemptuous observer it underscores the political ideologies that run parallel to ostensibly ancient religious stuff.

It is fitting indeed that Chick should oppose the Catholic Church: that was not an unusual aspect of populist xenophobia for much of the history of the United States. The Catholic presence, in short, would sap the self-reliance of America, knee bent to Rome, as sure as a later generation's participation in the U.N. would sop to collectivism. Americans are individuals; rebels. They shook away the chains of tyranny to live free, and the coming of the One World Government, then, as prophesied in Revelation, only confirms how throwing one's body to the feet of the Almighty is an act of profound self-determination. Because you are free, you can be saved, and the duty of the Christian, then -- saved already by the grace of God -- is to witness to others. It is a mistake to characterize Jack T. Chick as against the performance of good works, it's just that such altruism is irrelevant to the self; it is relevant only to demonstrating the ideal state, by which others may draw the inspiration needed to elect the individual option to be born again.

You don't need a mass.

You don't need a priest.

You don't need a church.

And all you need is the word of God, and maybe... a helpful demonstration.

* * *

You love to eat tasty foods. "It's my only vice," you think, as you wonder where you will eat lunch tomorrow. There is a new sushi place downtown. When you wake up in the morning, you can't taste or smell anything. You have a cough, and you call off work. You are very glad you work in an understanding office, and you wonder how the rapid test will interact with your insurance. That night you are gasping and coughing for air. You cannot drive, you think, oh my god, you reach for the lock on your apartment door so they don't have to break it down, that would cost money you cannot afford. You want, distantly, to text your mother, but you don't see your phone again. Yelling yelling tired, they told call you sorry, white painted walls. It hurts, a little. Then cold; nothing.

The commentator smiles. “We don't need any restrictions, at all." That gets them tittering from the naughtiness of it. "If we didn’t do anything, our lives would be better. Better economy. People would actually be going to work.” Laughter. “Any of us could die at any moment." Now the rosy grin of wisdom. "It would teach us to live life to the fullest, every minute." His grandson is running around in the yard. The child slams into a fence, and a bird's nest falls from the top. A tiny chick tumbles out onto the ground. There is shouting in the sky as the surrounding flock screech, circling above. The boy laughs and runs to get a toy. The commentator feels a well of tears forcing itself out like a creature wriggling upwards from the ocean at night.

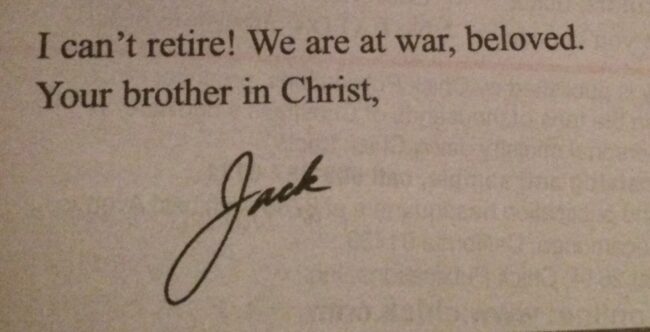

Jack Chick never doubted the efficacy of art. The efficacy of art is that it can cause pain. To hurt people, immediately and meaningfully, to push them toward a goal that Chick did not need or want to be alive to witness. Art affects the world, because art is war.

* * *

There's one tract I'll be taking to my grave, I love it so much. It's titled Somebody Goofed . Drawn by Chick himself, it begins with a guy laying dead on the ground from an overdose of speed while a hulking dude in a black pentagram t-shirt is going WOW! WHAT A DRAG! – it's great. This local kid is standing around, aghast, and before he knows it a hipster slithers up, jacket over a turtleneck shirt; Jack Chick was way ahead of the game on hipsters.

So the hipster starts telling the kid yeah, Bobby's in a better place, his problems are through. Soothing stuff, until this old man comes over and suggests that Bobby's problems are totally not through, because where is he going to spend eternity? And the hipster starts cracking up at the sight of him, and maybe we're cracking up too, just like they're cracking up at the offices of Chick Publications, because Chick is not stupid. He knows -- and knew, even then -- that people are laughing at him, and he works that right into the script. The hipster tells the old man, if God is a God of love, why would he condemn people to torture unto fucking eternity? He tells him, look: the Bible contradicts itself! It doesn't make sense! Men put it together! The hipster becomes indignant, comedy boiling over to outrage, and declares the speech of the older man, of Jack T. Chick, to be nothing more than fear-mongering. Nonplussed, the old man then hands the boy a little booklet not unlike a Chick tract: a mimesis, then, of the probable circumstances which delivered Somebody Goofed into your hand, closing the allegorical circuit on the give and take of emotional and logical impulses the author can presume, from experience, that you are facing.

The hipster rips up the tract, and he and the boy hop in a car. As the boy drives, the hipster tells him that all you need are the Ten Commandments; all you need is Love Thy Neighbor. This is bullshit. If you believe that you deserve to burn in Hell. “You are your own salvation!” the hipster declares, as they approach a set of train tracks. An engine is approaching. “I don't think I should!” the boy says, worried that he too will die of speed. “Go ahead! You can make it!”

WHAM.

The boy is in a cave. The hipster tells him that this is where souls go, temporarily, before they stand before the Great White Throne. He cannot accept Christ now. Only the lake of fire awaits. And the boy goes YOU GOOFED, and the hipster goes no, you did, and he takes off his mask – and it's Satan!!

No autobiographical comic, my friends, has ever been so astute.

* * *

Art: You work six years on something, then a critic grades it a "C+" after skimming half of it between their two day jobs. 150 years pass; you, them, and everything you've done is gone and forgotten. Your kids are dead.

But sometimes art endures a little while longer. Jack Chick died in 2016, but his work continues its ill effect, warping and bending around every contemporaneous critical reading. cat yronwode, in the '70s; who sought to divorce aesthetics from intent. Robert B. Fowler, in the '90s; who chased the ironies of cataloging all of Chick's peccadillos. Dan Raeburn, a year later; literary and political criticism, shot through with the worried thrill-seeking of the subcultural connoisseur. The No Context Chick Tracts Twitter account, since 2019; trafficking in absurdist mockery that offloads the burden of history to the audience. Me, now; whatever this is.

It is like staring into the face of an angel: an ever-shifting instrument of judgment.

* * *

I knew this guy who ran a pizza place where I used to work – an older man with deep roots in the Pittston, PA area; his mother knew all the guys from The Irishman. He was basically healthy for the longest time, and then he found out he had cancer, and it was all over within a month or so.

One of my friends still helped out with shop every so often; he'd go and visit this guy, and stayed in contact with his family. They told him at one point they knew knew the end was near, because from his sickbed the dying man had a vision.

Through the opioid mist common to pain management, he began conversing with a child, which nobody else could see – broken fragments of conversation, maybe half inside his head, but enough uttered aloud that the other family members in the room could discern that he was talking to a brother of his, who had died as a baby.

Now we are all rational people here, so I'm going to presume we understand that this dialogue was predicated upon a manifestation of this man's memories. And by memories, I don't just mean recorded experience, but the suppositions that become as real to us after a while as tangible events. There is a lot of fantasy to recollection, and fantasy, in this way, is experience, and in his state, what occurred to this man was a breakdown between experience-as-observed and experience-as-recollected.

I don't if we can expect this to happen to us when we die, though we can be certain that we will, in fact, die.

And in those last hours, days, months, when we're thinking “oh wow, this is real, this is really happening” -- as certain as when you're hovering over a toilet thinking “I didn't believe I was gonna throw up tonight” you're thinking “I didn't think my life was really going to end” -- I suspect Jack T. Chick, who has pondered this banal certainty often, is counting on the power of comics to win.

He's betting that you'll remember the cartoon truckers, the swarthy outlaw and the hipster who was Satan, and while you'll remember too the times you laughed at old JC - he never really minded. Because he knew by mocking him, by castigating him, by analyzing him, by 'understanding' him, you would instill him inside you, and maybe in that one crucial moment, at the portal to something you don't understand, the cold nothing, the cold, cold black nothing, maybe, maybe, maybe you'll be into a sure and simple thing, a comic book in the most vulgar and negative sense of the term, a caricature and a simplification, a needle driven into your presuppositions, an assumption too basic too catch in the mesh of your logic, your decaying logic, your precious logic, dying, your cultivation, your intellect, dying, dying, and that is when you'll remember you don't need a church, or a priest, or anything else, and you'll think:

“Well, why not?”

* * *

* * *

IMAGE KEY

1. Chick, from The Next Step for Growing Christians, 1973

2. Carter, from Jonah, 1994

3. Ibid.

4. Carter, painting from the motion picture The Light of the World, screengrab, 2003

5. Traditional prayer card illustration; artist unknown

6. Chick, from Gun Slinger, 1997

7. Ibid.

8. Carter, from King of Kings, 1980

9. Ibid.

10. Carter, painting from the motion picture The Light of the World, scanned from a print catalog image, 2003

11. Chick, from Somebody Goofed, 1969

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Chick, from This Was Your Life!, 1964

16. Ibid.

17. Carter, painting from the motion picture The Light of the World, scanned from an art print, 2003

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Scanned from the Chick Publications Battle Cry newsletter