Blue Delliquanti and Dylan Edwards are both cartoonists working in the field of queer and trans speculative fiction for kids and teens. In this interview, they talk with Melanie Gillman about the power of LGBTQ spec fic as a genre to challenge existing infrastructures, provide escapes, and create allegorical mirrors for young queer and trans readers.

Blue Delliquanti and Dylan Edwards are both cartoonists working in the field of queer and trans speculative fiction for kids and teens. In this interview, they talk with Melanie Gillman about the power of LGBTQ spec fic as a genre to challenge existing infrastructures, provide escapes, and create allegorical mirrors for young queer and trans readers.

Melanie Gillman: We're here to talk about queer and trans spec fic comics for kids and teens! Which is an area you both work in. I wanted to start with a general question. What were some books/media, if any, that appealed to you on that level as a kid? Were you able to find any?

Dylan Edwards: My answer is very simple: there was basically nothing. I grew up in the 80s, and there wasn't anything marketed to teens that had any queer characters. The first book I remember encountering was the Magic’s Pawn series, by Mercedes Lackey, in high school.

Blue Delliquanti: I have one that's an extremely common origin story, from what I've heard—Sailor Uranus. In the original manga, she was bigender, and in the anime, she was portrayed more as a butch lesbian. And when it was first distributed in the States, the dub version had changed the lesbian relationship into them being cousins. Which was really weird! But the internet was just omnipresent enough that me and my friends were able to figure it out. The only western series that's coming to mind from that time period for me was [The Circle of Magic] by Tamora Pierce. Everything else is all Sailor Moon, Cardcaptor Sakura, etc.

Melanie Gillman: These examples are also oftentimes escapist fantasies for kids. Could we talk about that? What's the value of work where the main priority is just fun, for queer and trans kids?

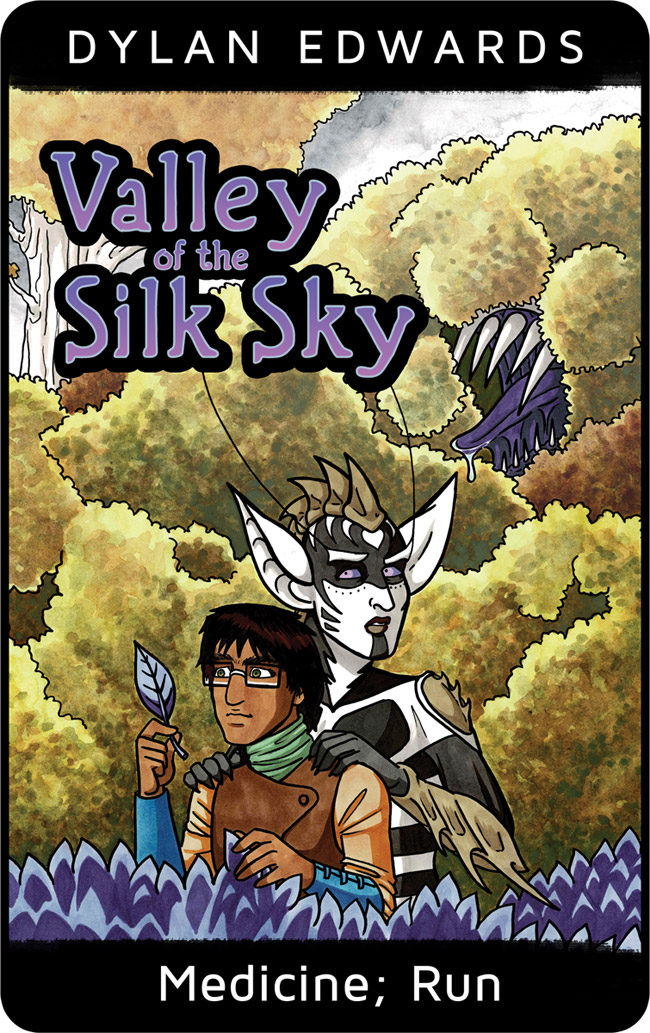

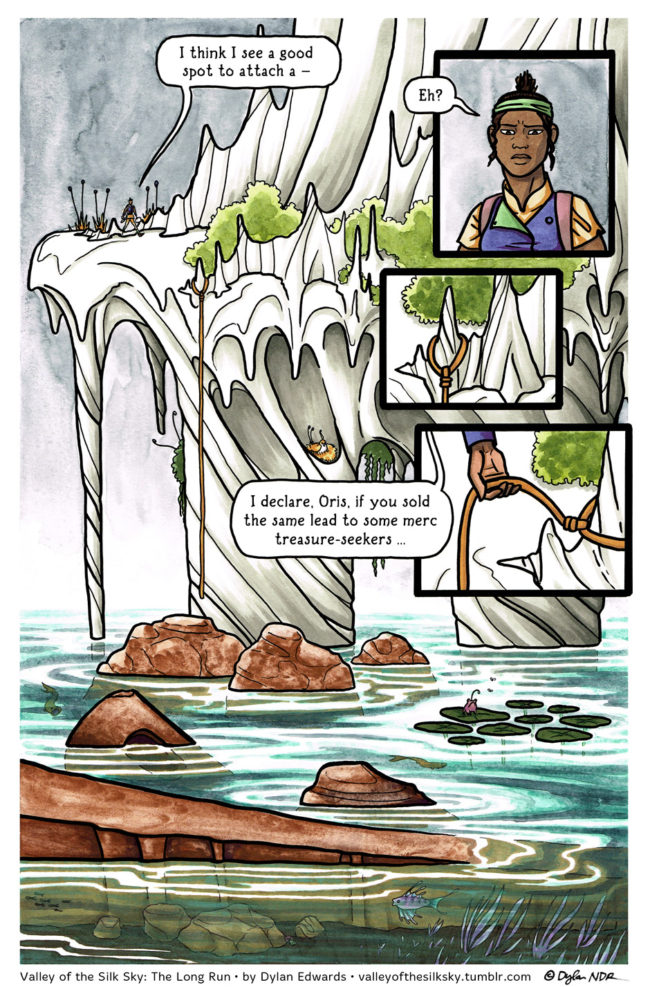

Dylan Edwards: That was the main goal for Valley of the Silk Sky. I've done so much work already that's about complicated identity issues and it's like, for once, can we not?? Can we just go outside and play?? I want queer and trans characters to be centered, but sometimes I as the writer need a break from identity issues. Growing up I read a lot of fantasy and sci fi, because I liked being inside someone else's imagination for a while. When we talk about spec fic, the biggest question is, how do we reimagine society itself? How would other people under other circumstances exist? How do trans people exist within a society built upon different social mores? As an author, I make up those restrictions, but then I ask, how do people move within those spaces?

Dylan Edwards: That was the main goal for Valley of the Silk Sky. I've done so much work already that's about complicated identity issues and it's like, for once, can we not?? Can we just go outside and play?? I want queer and trans characters to be centered, but sometimes I as the writer need a break from identity issues. Growing up I read a lot of fantasy and sci fi, because I liked being inside someone else's imagination for a while. When we talk about spec fic, the biggest question is, how do we reimagine society itself? How would other people under other circumstances exist? How do trans people exist within a society built upon different social mores? As an author, I make up those restrictions, but then I ask, how do people move within those spaces?

Blue Delliquanti: You don't realize how much RAM in your day-to-day processing system is taken up by just, like, justifying your existence. It's really interesting to see a character like yourself in a speculative world. I like to play in the same playground as Dylan, where I'm really interested in infrastructure.

Dylan Edwards: I think this bounces back to the concept of seeing yourself in media in the first place. If you had told me as a 12 year old that asexual was a thing you could be, that would have changed my life. One of the things that spec fic allows you to do is ask things like, what if society wasn't transphobic to begin with? What if trans people's humanity was just accepted as fact?

Melanie Gillman: I'm glad both of you brought up spec fic as a means to imagine different possible ways to construct societies around queer and trans people. That's a thing we tend to forget about the actual world we live in, that all our social constructions are basically made-up inventions here too. But spec fic can be a way to point the finger at that. These are things that we as a human society have built over time—and how well or poorly queer and trans people can be situated within those constructions is an arbitrary thing we came up with.

Dylan Edwards: We constantly get this lie sold to us, that it's “natural” to be cis and straight, but those concepts were essentially invented in the 1800s. Enough generations have cycled through since then that by now, people have forgotten.

Blue Delliquanti: Even just the idea that the things that queer and trans people ask for are completely out of the question or a huge drain on everyone. When they're not! There are plenty of equivalent resources that straight and cis people access every day with very little fuss. But the idea is that if queer and trans people ask for that same thing, it's a problem.

Melanie Gillman: I think about that every time I pass one of those billboards advertising testosterone supplements to cis men.

One thing both of you have in your work are non-human characters with queer or trans identities. I know this is a complicated issue, because dehumanization is a real-world problem that queer and trans people deal with all the time. And so much media uses non-human monster characters as inserts for “the other”. How do you navigate this in your own work?

One thing both of you have in your work are non-human characters with queer or trans identities. I know this is a complicated issue, because dehumanization is a real-world problem that queer and trans people deal with all the time. And so much media uses non-human monster characters as inserts for “the other”. How do you navigate this in your own work?

Dylan Edwards: This is one of my favorite topics in the whole world. I've talked to quite a few other trans people who had this experience—we didn't have representation growing up, so we instead related to monster characters. Monsters don't have the same societal expectations placed on them as human characters. But you bring up a valid point, that a lot of times these monster characters are stand-ins for the other. One of the things I always wanted to make clear in my stories are that the humans are as diverse as can be, and so are the monsters. The monsters have different races and genders and sexualities, the same way that the humans do. Often in spec fic the monsters are presented as this monolithic species, where every individual monster is exactly the same as all the others—but that's not true even on this planet, in the actual animal kingdom.

Melanie Gillman: Yeah, our own planet already has a fungus species with like, 23,000 sexes.

Dylan Edwards: Yeah, you can't out-weird nature! For every possible facet of the cis-hetero binary, there’s some living thing on this planet that breaks those rules.

Blue Delliquanti: It challenges human imagination, too.

Dylan Edwards: I do a lot of nonfiction around queer and trans issues. One thing that's relaxing and fun for me is asking questions like—how does it work if you're trans in a species that has 5 different body types? What does it mean to be queer within that group?

Melanie Gillman: Monster fiction also has a sort of historical queer precedent to it. If you were an author living in a more homophobic time period, and you wanted to talk about queer issues in your book, you were often given a lot more moral leeway by your readers if you made those queer characters be monsters. Like, “oh these characters might be lesbians, but they're also vampires, so y'know in the grand scheme of things...”

Blue Delliquanti: Queer monster stories are also about power fantasy. Like, I may be rejected by society, but at least I can turn into a wolf too! That's something I definitely find appealing about the queer monster narrative. You might face hostility from society at large, but you can give as good as you get. With robot narratives, though, I tend to approach them not as the robots being monsters. In O Human Star, it's more about what happens when your likeness is taken out of your control, and there are different iterations of yourself—but each one of those iterations can go on to live lives of their own. As queer and trans people, often we can look back on our lives and see ourselves as 5 or 6 different people, acting independently. But artifacts from those past selves can be so difficult to expunge from the public record sometimes.

Blue Delliquanti: Queer monster stories are also about power fantasy. Like, I may be rejected by society, but at least I can turn into a wolf too! That's something I definitely find appealing about the queer monster narrative. You might face hostility from society at large, but you can give as good as you get. With robot narratives, though, I tend to approach them not as the robots being monsters. In O Human Star, it's more about what happens when your likeness is taken out of your control, and there are different iterations of yourself—but each one of those iterations can go on to live lives of their own. As queer and trans people, often we can look back on our lives and see ourselves as 5 or 6 different people, acting independently. But artifacts from those past selves can be so difficult to expunge from the public record sometimes.

Melanie Gillman: Yeah, because with the internet, so much of the public record is out of our hands.

Blue Delliquanti: It's a little harder now than just moving to a new town and starting a new life. We don't have that luxury anymore.

Melanie Gillman: That's one of the reasons why you hear historians say things like, “oh, there were no trans people in the past.” Actually, if you were a trans person living in the past, oftentimes what you did was pick up and move to a completely different place, and start a whole new life away from everyone who ever knew you. The historical record had a hard time following those people, by design!

Blue Delliquanti: It's like, if you succeeded in living your life without hostile scrutiny, then the price of that was making yourself invisible in the public record. And so many of the trans historical figures we do know of today are people who were outed after their death.

Something I've also been thinking about with robots is how you can be the kind of entity who's several things all at once. Have you read Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice? I really like the idea of there being a being who can have multiple simultaneous identities, but is also part of a collective entity.

Something I've also been thinking about with robots is how you can be the kind of entity who's several things all at once. Have you read Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice? I really like the idea of there being a being who can have multiple simultaneous identities, but is also part of a collective entity.

Dylan Edwards: With robots too, you're talking about beings that are explicitly manufactured for a purpose. People chose their job for them. The robot is often a great metaphor for queer and trans narratives, because the humans are like “you were made for this purpose and will do this thing”, and maybe the robot's like “okay but what if I don't??” That narrative you've been programed with doesn't always work for you.

Blue Delliquanti: With certain parameters, an artificial being can have a way broader perspective than whatever human society had programmed them for. We think of robots as being very rigid, unadaptable characters, but that doesn't have to be the case.

Melanie Gillman: Another question. One of the things I still sometimes hear when I'm talking to straight cis people is this concern that works that are both LGBTQ and spec fic are not marketable. Like “it's too niche, it's not going to appeal to a wide enough audience,” etc. What do you say to that?

Dylan Edwards: I've been doing conventions for over 15 years. I've gone from having the people who approach my table be exclusively queer adults, to having parents coming up and asking what they can buy for their queer kids, to the kids themselves dashing across the convention hall when they spot the “queer comics” sign. Teens today are unapologetic about themselves. They really love stuff that's just: here's a character who's like you, running around in a fantasy environment and having fun. The idea that there's not a market for this genre baffles me. The kids are demanding it; they're practically ready to beat down the doors. My generation, we grew up being told by society that being straight and cis is a requirement, and we had to figure out our gender and sexuality on our own. But these kids already have friends who are openly queer and trans. They understand gender and sexuality intuitively in a way a lot of adults can't wrap their heads around.

Melanie Gillman: It really is those adult gatekeepers who are the obstacle, yeah.

Blue Delliquanti: I'm currently working on a book for Random House that is super duper queer. The main characters are both nonbinary, and there's a lot of discussion of transmasculinity. I had to check in with my editor like, “is this going to fly?”, but they don't even bat an eyelid at it. Having an overtly trans story, and getting zero editorial pushback for it, is really interesting in comparison to the year I've had with O Human Star. I've always had a pretty substantial readership that's older queer men—like, they come up at conventions and are visibly surprised to see me as the creator of the book. In the last year, there has been a more explicit coverage of transness in the comic—instead of just an allegorical use. Different demographics of my readership have responded very differently. Some readers really clung to the idea that the trans subtext was only an allegory—thinking it's just about this character not being a human anymore, etc. Meanwhile, this whole other subset of my readership was like “I knew it, I clocked this character as trans back in 2013!” Some people are thirsty for that trans content, other readers are more comfortable thinking of it as allegory.

Blue Delliquanti: I'm currently working on a book for Random House that is super duper queer. The main characters are both nonbinary, and there's a lot of discussion of transmasculinity. I had to check in with my editor like, “is this going to fly?”, but they don't even bat an eyelid at it. Having an overtly trans story, and getting zero editorial pushback for it, is really interesting in comparison to the year I've had with O Human Star. I've always had a pretty substantial readership that's older queer men—like, they come up at conventions and are visibly surprised to see me as the creator of the book. In the last year, there has been a more explicit coverage of transness in the comic—instead of just an allegorical use. Different demographics of my readership have responded very differently. Some readers really clung to the idea that the trans subtext was only an allegory—thinking it's just about this character not being a human anymore, etc. Meanwhile, this whole other subset of my readership was like “I knew it, I clocked this character as trans back in 2013!” Some people are thirsty for that trans content, other readers are more comfortable thinking of it as allegory.

Dylan Edwards: It's interesting to think about allegory and metaphor, when you're creating something that's explicitly queer and trans. I have allegories in my work, but they're not about queer and trans identity. More like, here's a thing that'll be visible if you want to find it, but not if you don't.

Melanie Gillman: I had kind of a similar experience with As the Crow Flies, with Sydney. For the most part my trans readers knew right away, and everyone else had to catch up. That's the thing about allegory—if someone has personal experience with the subject you're writing about, then the allegory functions as a mirror for them. But other readers won't necessarily see it the same way.

Blue Delliquanti: There's a language of tells, but only if you're in a place to recognize them. With O Human Star, I’ve learned that many female readers are trans women who had gotten into computer programming or IT, a path common enough to develop into a queer archetype. For them, seeing a character like Sulla was very “oh yeah, I recognize that kind of girl.” But that might fly over the head of people who haven't met someone like that.

Melanie Gillman: The last thing I wanted to ask is what's in the future for you? What are you working on?

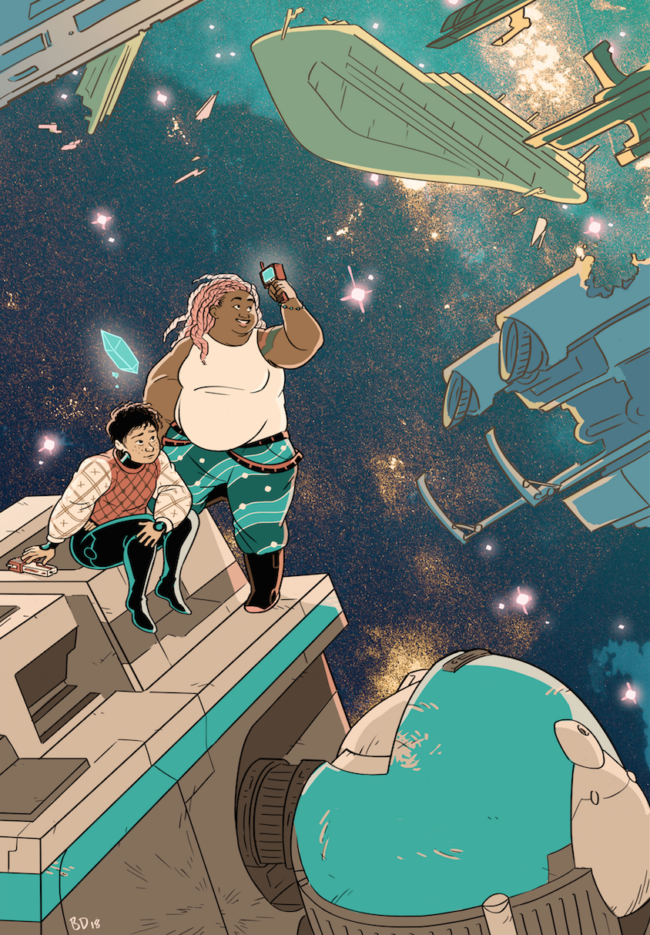

Blue Delliquanti: The book I’m working on for Random House Graphic is currently titled Across a Field of Starlight. I've been describing it glibly to different audiences either as, “two kids from different space societies become pen pals,” or “anarcho-space communism for kids.” Kids today are beyond that initial step of queer acceptance. I'm very interested in talking about creating queer infrastructure in utopian societies. The thing I've learned is that kids are way savvier to queer concepts than a lot of adult gatekeepers give them credit for.

Dylan Edwards: I'm still working on my graphic novel, Valley of the Silk Sky. I have about 60ish pages left to go before I finish the story. I'll be looking for a publisher after that, somewhere with distribution to schools and bookstores and libraries. I want to get the thing thumbnailed, then possibly start pitching it after that. That's the big thing on my plate! It's a book I've been working on for four years, and will hopefully be done with in one more year.