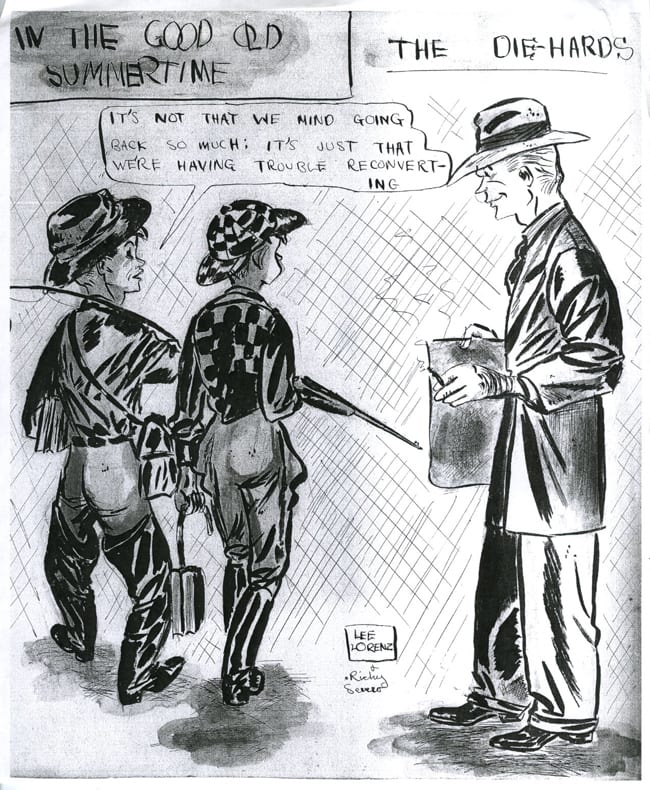

"So much for kinetic art, eh Leo?" asks a classic espresso-sipping bohemian of her wildly spinning friend in a 1965 Lee Lorenz cartoon. Many of Lorenz's best drawings caricature the modern-art world from which one might say he escaped – note the whirling artist's name – to become one of The New Yorker's more prolific artists, the magazine's second second art editor, and the first, and best, historian of its imagery. Born in 1932, Lorenz won a New Yorker contract in 1958, served as the magazine's art editor from 1973 to 1993, and retired as its cartoon editor in 1998. He still contributes to the magazine regularly.

Published in 1995, Lorenz's The Art of The New Yorker: 1925-1995 is a remarkable contribution to the history of both the magazine and the art form it now almost single-handedly nurtures. As an editor, Lorenz often took it upon himself to celebrate the talents of his colleagues in elegant obituaries. "On paper," he wrote upon George Price's passing, "the Pricean line was whiplike and beautifully finished; when lasers came along, they at last provided an image that befitted such exactitude." Lorenz describes the tribulations involved in writing another fascinating book, The World of William Steig, below.

These days, Lorenz's brush strokes provide rich visual contrast to the pen-preferring cartoonists who dominate The New Yorker. Like the abstract expressionists he studied at Carnegie and Pratt, Lee's lines radiate a lively in-the-moment quality. He often captures characters in motion who just happen to make you laugh out loud. And there's an improvised aspect to his work that echoes both his own abstract-expressionist paintings and the jazz he began devoting himself to as a teenager.

In fact, Lorenz has been a professional jazz trumpeter since high school. He currently leads his own Dixieland ensemble – the Creole Cookin' Jazz Band – on cornet every Sunday evening at Arthur's Tavern in Greenwich Village, where he's been playing for three decades. And beginning again in September, you can dig Lorenz with the Gotham Jazzmen every Tuesday at noon at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

I visited Lorenz in his serene Easton, Connecticut, home, which has a rustic, improvised feeling not unlike his cartoons. Wood sculptures that he's constructed, folk art that he's acquired, and found items that split the difference between production and consumption are scattered about. It was a great place to hang out for an afternoon as Lee spilled the behind-the-scenes beans on life at The New Yorker.

RICHARD GEHR: Where did your path to the magical land of cartooning begin?

LEE LORENZ: I was just thinking about the early part of my life, because most of the people I know who've gotten into this field always wanted to be cartoonists. I was thinking particularly of Jules Feiffer’s autobiography, which is very good as you might imagine. It’s interesting how early on he decided this is what he wanted to do, and the thoroughness of his preparation for it. He was drawing comic books when he was a kid. He analyzed the structure of comic books: how long it took to tell the story, how you move from one section of the story to the next. So when he had a chance to work with Will Eisner, he was already very knowledgeable about the whole business. That’s remarkable.

GEHR: So did you always want to be a cartoonist?

LORENZ: No. Even though my parents subscribed to The New Yorker, and I looked at it all the time, I never really got interested in cartooning until I was in high school. I’d already gotten a lot of attention for drawing; I had a gift for it. Saul Steinberg got me interested in that branch of art. His first collection of drawings was published when I was in high school, and it knocked me out. You can also see a very strong Milton Caniff influence in the sketches I did for a friend when I was fifteen. Later, as a senior, I was asked to design and illustrate the yearbook. I'd already written a satirical class history for it and decided to illustrate the yearbook in the same spirit. The drawings were very influenced by Steinberg and Gene Deitch, who was fantastic. Deitch also did animation and a lot of drawing for a magazine I used to get called The Record Changer.

GEHR: Deitch's album art is collected in that terrific book, Cat on a Hot Thin Groove.

LORENZ: Well, back then, I was more interested in music than art, especially early jazz. I put whatever money I earned walking dogs or whatever into buying records. I had my first real art teacher in Greenwich, Connecticut, where we moved from Newburgh, New York, when I was a sophomore. I had a wonderful teacher named Lucia Cumins who introduced me to a whole new world of art. We’d moved around a lot when I was a kid and none of these schools had an art program of any kind.

GEHR: Where were you born?

LORENZ: I was born in Hackensack, New Jersey, on October 17, 1932. We lived in White Plains, New York, until I was about nine or ten.

GEHR: What did your parents do?

LORENZ: My father, Alfred, worked for the YMCA. We started moving around during the war because the YMCA used to administer the USO programs. He was put in charge of the USO program in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, so we moved out to that poor little town. Even though White Plains was small, it had a very nice school system with a little orchestra I joined in fourth or fifth grade. We lived there for a couple of years and then moved up to Newburgh, where the Stewart Air Force Base was located. In 1947, we moved to Greenwich. Greenwich High School was a revelation. They had wonderful teachers and a lot of very talented kids. I was crushed on my first day of school because it seemed as though everybody was able to do anything. The kids in music class could all sight-read.

GEHR: Were your parents artistic?

LORENZ: Martha, my mother, was the reason we had The New Yorker around. She always wanted to be a writer or a poet but never got much further than the greeting-card business. My father wasn’t interested in the arts at all. His passion was cycling. He was into the youth-hostel movement and used to take kids on summer trips. I was the only kid in the neighborhood who had a bicycle with gear shifts and handbrakes. Everyone else was riding a Schwinn.

GEHR: When did you get interested in art?

LORENZ: The Greenwich High School environment really excited me. Lucia Cumins was already into the abstract expressionists in 1949. She was wonderful, a real tough New England type. I’d seen William Steig's work in The New Yorker for years and never paid much attention to him. But she lent me Listen, Little Man, a book he illustrated by the radical psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Steig's illustrations were very powerful. Ms. Cumins taught me to look at things in a different way. It was liberating to move into a community that had access to that kind of teacher. I also had a wonderful English teacher, Catherine Wood, who encouraged me to write.

GEHR: So you weren't seriously into cartooning in high school?

LORENZ: No, but what I did in the yearbook suggested I should try it. So when I was trying to figure out how to make a living several years later, I was encouraged by Jack Morley, the father of a classmate. Jack used to work on "Barnaby" with Crockett Johnson. He'd also worked with Fontaine Fox on "Toonerville Folks." He never did his own strip, but he knew the business. So I gave it a shot, and it happened to be an ideal moment to move into cartooning. There were all kinds of magazines out there, so if you could do anything passable, you could sell it.

GEHR: Were gag cartoons the first comics you loved or were you a comic-book guy like Feiffer?

LORENZ: I was not a comic-book guy. In fact, when I was a kid I don’t think I was allowed to have any action comics. I had Donald Duck, so cartooning to me was Walt Disney. I loved Disney pictures as a kid. I still remember the songs from a lot of the movies – which I thought were really great, like the three crows in Dumbo – and I would draw that kind of stuff. But I wasn’t really interested in comics. The only artist who made an impression on me was Milton Caniff. Long after the fact I realized that what I loved was the rich brush quality of his drawings. As a kid I didn't know you could draw with brush. I drew with a pen I got at the ten-cent store. I loved and responded to the graphic richness of his drawings.

GEHR: That's definitely an aspect of your own work, too.

LORENZ: Thank you. Part of the fun when I started out was working in color. Esquire and a lot of the Playboy imitators used color, too. You could do a lot with ink, watercolor, and Pentel. But I didn’t really care about the comic strips. I wasn’t interested in the stories.

GEHR: Did you attend college or art school?

LORENZ: I started at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where I had a scholarship, but I didn’t stick it out, unfortunately. Living in Pittsburgh was tough back then. So I came back to New York and I got a BFA from the Pratt Institute.

GEHR: Did you ever regret giving up painting for cartooning?

LORENZ: My mother considered herself "artistic," and she had a strong musical background. Her sister was a child prodigy and had a successful career as a concert pianist. But I never went to a museum until I was in high school. I was very ignorant. By the time I went to Pratt, I was very influenced by what was going on, particularly abstract expressionism. That’s what I pursued when I got out of art school, but I still needed to make a living. That's how I got into cartooning.

GEHR: Do you still paint?

LORENZ: I do, but I have a chronic problem doing it. Once in a while I paint something, and then I just have trouble doing it. A few years ago, someone asked me to put together pieces for a show. I did all kinds of stuff, paintings and constructions.

GEHR: It sounds as though you treated it as an assignment.

LORENZ: Yeah, I depend on the assignment. There’s a funny disconnect there. It’s hard for me to just sit down and do it. I have a big studio space here, but right now it’s just a mess. You couldn’t work there if you wanted to. It’s full of drawings that haven’t been properly cataloged and art that's still framed from wherever it had been shown.

GEHR: What kind of paintings are you interested in doing?

LORENZ: A couple of months ago there was an article in The New York Times about an animated Woody Woodpecker cartoon in which he explodes. And in the middle of the explosion, the artist included something that looks like an abstract-expressionist painting. That was such a great idea. I thought it would be a nice challenge to take a SpongeBob explosion, for example, and paint one panel mid-explosion using the elements of SpongeBob. You'd never run out of characters, and you could highlight a glove or an eyeball to tell you which one it is. I get ideas like that, but it’s hard for me to follow through.

GEHR: You've also done many cartoons that are about modern art.

LORENZ: Oh yeah. Philip Guston was one of my teachers at Pratt and became a very good friend. He was best man at my wedding. I’m a great admirer of his work, especially after he turned his back on what became "classical" abstract expressionism. He started doing what people would later call "cartoon figures," not really cartoons. I had lunch with him one day when I was feeling down, because I hoped I would make some sort of career as a painter. He said, "Let me see what you’re doing." Well, the cartoons I was doing were certainly not good or very interesting graphically. He told me, "You shouldn’t feel that way. This is a really vital and interesting art form. You should be pleased you can do this." I thought he was pulling my leg, but he utilized a lot of cartoon clichés himself many years later. This was long before he had that epiphany and changed his whole approach to his art.

GEHR: Who else did you study with at Pratt?

LORENZ: James Brooks and George McNeil were there, but I never studied with them. When I got out, I didn’t have the vaguest idea how I was going to make a living. I just fell into cartooning and it turned out I had a real knack for it. Especially the idea part, which I feel was the biggest stumbling block for most people.

GEHR: Did you go into the service?

LORENZ: No, I married a classmate right out of college. I had a deferment. I was never in the service.

GEHR: But you had to bring home the bacon.

LORENZ: I started making the rounds at little magazines. I had a book with a list of cartoon markets. I began selling long before I had a sense of personal style. Gag ideas turned out to be very easy for me. After a few years, everybody in the business said, "If you want to make money you have to go to The New Yorker." So I began submitting there.

GEHR: What other magazines were you selling to?

LORENZ: I was selling to all of them: Post, Look, True, Argosy, Playboy, and all the Playboy imitators. Then there were magazines like 1000 Jokes, where you’d go at the end of the day with whatever you hadn’t sold. The editor was a sympathetic comic-strip artist named Bill Yates, and I'd always sell five or six drawings there for $20 apiece. I was able to make a living out of this early on and did quite well.

GEHR: When did you make your first New Yorker sale?

LORENZ: They began buying my ideas in 1956 and farmed them out to their contract artists. After selling them quite a few ideas, they said yes when I asked if I could try to do my own art. But I couldn’t seem to pull it off. I still wasn’t quite sure what my style was. Frank Modell, an assistant to Jim Geraghty, the cartoons editor, was very helpful to me. He looked at my stuff, made suggestions, and eventually I managed to sell a drawing. It was interesting. I was offered a New Yorker contract before I published a drawing. Geraghty invited me to his office and gave me a bunch of OK'd ideas. Then he took me down to meet William Shawn, who offered me a contract. The first drawings I published were from that group of roughs.

GEHR: Your first cartoon in The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker

shows a American soldier writing "Yankee go home" on a wall in Europe.

LORENZ: Is that in there? I thought I did that for Sports Illustrated. No, that wasn't my first New Yorker cartoon. My first was a nondescript drawing, some gorgeous airhead talking to a sugar daddy. I don’t even remember the caption. They were very indulgent.

GEHR: How much did they pay for a gag for back then?

LORENZ: I think a gag was around $25 and a cartoon paid $150. The New Yorker had amazingly elaborate contracts. Harold Ross thought artists should be paid according to how much space they took up in the magazine. I started long after Ross was gone, but the contract was still for so much per square inch of published drawing. So of course everybody submitted the largest drawings they could. You also got a quarterly increase in your base rate and a bonus at the end of the year. It was very complicated. After a year or two I was selling very well there – so much so that I bought a little house in Connecticut. Then I had a kind of breakdown in the early sixties, and I couldn’t seem to finish a drawing.

GEHR: How did you get over that hump?

LORENZ: The weird thing was that I was still doing drawings for everybody else. I could finish them, but I could not seem to finish drawings for The New Yorker. But Jim Geraghty and William Shawn were extremely generous to me. They OK'd a large batch of ideas and let me draw from that account every month. I finally got past it with some professional help. But it was odd to be able to do one thing and not the other. I guess I thought there was so much more at stake with The New Yorker. Eventually, I went on to sell steadily, forty to fifty drawings a year.

GEHR: How did The New Yorker's art department operate back then?

LORENZ: Geraghty really created the job. They hired him because he'd been a gag writer. They’d never really had an art editor before. Rea Irvin was on staff, but he wasn't a real editor; he never wanted to deal with the artists. Someone from the fiction department – which was run by Katharine White – would act as an intermediary between the art meeting and the artists. I think Peter Arno suggested they ask Geraghty if he’d like to do it, because Geraghty had sold a lot of ideas directly to Arno. Geraghty grabbed it and turned it into the kind of art department the magazine has today.

There's a letter in The Art of The New Yorker in which Harold Ross says, "I think the problem with the art department has been solved." He was talking about Geraghty, who gradually took responsibility for the covers and small spot illustrations. And that’s what the job was when he retired and I took over. It wasn’t just the cartoons: It was all the artwork in the magazine.

GEHR: Gahan Wilson says he was shocked to learn that artists used other people’s gags. How did you feel about it?

LORENZ: If they were my ideas, I thought it was great. The first gag I sold was drawn by Richard Taylor, who was quite a draftsman and also a painter. It was a full-page drawing. I sold several to Charles Addams, and some went to George Price.

GEHR: And Sam Gross was shocked when a gag he sold to Addams fetched tens of thousands of dollars when the Addams estate sold the original art.

LORENZ: Sam is no shrinking violet. He’s got an idea about what his work's worth, and more power to him. It’s been a long time since cartoonists organized themselves. Sam and I worked together in the Cartoonists Guild, which actually got some magazines to raise their rates. I was its first president.

GEHR: What made it so successful?

LORENZ: We had an ambitious agenda and everyone got involved. Sam was very involved, and so was Gahan Wilson. I think most of the younger magazine cartoonists were in it, people like Don Reilly, George Booth, and Charlie Barsotti. In fact, I just came across a booklet Don wrote for us about doing children’s books. Our primary goal was to get artists to work together. It was very much a cooperative in the beginning. Henry Martin edited our monthly newsletter, "News of the Marketplace," and we had two- or three-member teams that would try to negotiate with the magazines. If you want to raise rates for everyone, and some guy goes out and takes whatever they give him, you’ve got a problem. We discovered that Charles Preston, who I think still does "Pepper…and Salt" for The Wall Street Journal, was paying his artist $50 while he was getting $200. Those figures may not be right, but the proportion is correct. We tried to go after him, but so many people were happy with that $50 that we never had any luck. The most successful thing we did was standardize the return of original art. That, and get magazines to pass along requests for reprints. Most magazines didn’t bother to pass reprint requests along.

GEHR: How did the Cartoonists Guild end?

LORENZ: We eventually hired a guy to run the Guild and it began to fall apart. It was successful until these guys tried to turn it into a business. They tried to act as agents for artists and nobody wanted that.

(Continued)