The past couple of years have been great ones for readers who enjoy both horror and alternative comics, thanks to the emergence of a powerful hybrid strain thereof. My personal Top 20 Comics of 2011 could well be the staff directory for some alternate-universe EC Comics that was never shut down, and at this point three of this column's five interview subjects work in the genre. But as I've said elsewhere, no one is wedding horror's darkness to an equally black, equally lacerating emotional palette as effectively as Julia Gfrörer. Her two recent single-issue comics Flesh and Bone and Too Dark to See treat mental and emotional agony as the door through which dark forces are permitted access to our world, their intervention coming across less like the traditional monster role of upending the status quo and more like that status quo's embodiment. When coupled with her intimate, delicate linework, the fragile physicality of her characters, and her explicit and non-idealized depictions of sex, the effect is gripping and even in our mundane world, ominously familiar.

Raised an only child in Concord, New Hampshire (she now has a thirteen-year-old sister, as well as a child of her own), the 29-year-old Portland-based artist studied illustration at Seattle's Cornish College of the Arts before graduating with a double major in printmaking and painting. I found her to be an enormously thoughtful interview subject -- days would pass between responses, and inquiries were usually greeted with an apology and the explanation that she was still thinking over the questions and how best to respond to them. It intimidated me into wanting to be a better interviewer, in much the same way that her work itself nearly intimidated me out of interviewing her at all.

Collins: I've spent the last couple of hours doing research, reading older interviews of yours, bouncing around your Flickr and Facebook, browsing the illustrations on your website ... and in all honesty, I think it's avoidance. I find your work very, very, very, very, very, very, very dark. Profoundly dark, I suppose. And this is an intimidating head space to attempt to inhabit for the purposes of an interview. I feel that by titling one of your comics Too Dark to See you may have already answered this question, but I'm wondering if you see your work that way as well -- as dark.

Gfrörer: Yes, I know it's dark. It's on purpose. I'm most interested in making art about feelings and experiences that are hidden or obscure, uncomfortable to talk about, frightening to even think of. It should be challenging for me to create, and for you to consume. I guess that it often comes off as overwrought and melodramatic, but like the song says, I can't come through half-stepping. I can't expect other people to take my work seriously unless I'm willing to take it even more seriously.

But having said that, I want to point out that I'm reading the fourth Song of Ice and Fire book as I write this, and those are mainstream popular and so much more dark than anything I've ever written. I mean, have you heard "Love the Way You Lie"? It was number one on the Billboard chart for seven weeks last year and it's about murdering your battered girlfriend when she tries to leave you. So in that context my work's not really that dark. Maybe I am half-stepping.

Collins: Ha, by bringing up A Song of Ice and Fire you have triggered one of my nerd buttons. I guess I would argue in the case of both George R. R. Martin and Eminem that the mainstream popularity and the darkness are basically separate phenomena -- Eminem was the funny white rapper before he realized that his abusive treatment of his wife was his muse, and the hundreds of thousands of people who flocked to the books after watching Game of Thrones on HBO probably have no idea what's in store for them beyond your basic grim HBO violence. In other words, don't sell yourself short.

Gfrörer: I get what you're saying here -- I definitely dwell on the dark elements in my work in a more personal way, it's more intimate and visceral than the violence in Game of Thrones, and more serious than Eminem, who mostly mines his darkness for humor. But I think people are perceptive of the grim aspects in the above and that's part of the attraction, people have a need for artists to discuss those subjects.

The title of Too Dark to See is from "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" and is not intended as a mission statement.

Collins: I'm actually glad to hear this, because I had the original Dylan version going through my head every time I came across that comic.

I wanted to talk to you in particular about the drawing of Dylan Williams you made after his death. You've surrounded him with the hands of a skeleton. I found this so troubling and so moving. In a show I've been watching recently, a character angrily accused other characters of ignoring the reality of a loved one's death: "He's gone," she said, "He's gone and he's never coming back." I feel like many tributes to Dylan, even my own, kind of shied away from that loss, focusing on his legacy. Which is a good thing, but not the whole story. Why did you choose to depict him this way?

Gfrörer: I drew that portrait on the morning of Dylan's funeral. I was trying to force myself to understand that he was gone, and the drawing helped, but it wasn't until I saw and touched his coffin that I fully believed it and broke down. I wish I could tell you how important Dylan was to me, the impact of his mentorship on my life, the depth of my sadness at his loss, but it would be crass to talk about that, I don't want to make his death about my feelings. It was nice that so many people wrote beautiful things about him when he died. I wanted to but I felt so inept, and like it wasn't my place. All I could do was this stupid drawing.

Collins: Tom Spurgeon made a similar argument, although in much less emotional terms. He was dismayed at the tendency for remembrances of comics people by comics people to run along the lines of "I had drinks with him one time" rather than talking about their work and impact. But his impact is, essentially, exactly what you're talking about.

I detect a similar refusal to pull punches in your treatment of sexuality. I've found the recent willingness of alternative comics creators to directly, explicitly address sex really bracing and encouraging, but I think you could fit most of them safely under the umbrella of sex-positivity. Those instances you can't are usually addressing something separate from traditional consensual recreational sex or masturbation, like rape or prostitution. But in both Flesh and Bone and Too Dark to See, you've depicted sexuality's potential sadness, destructiveness, and perhaps ironically, isolation. I think these are all qualities that can be present in human sexuality, but it's been a long time since I read a comic that graphically depicted sexual activity in this light. Have you seen any other work you feel goes where you've gone?

Gfrörer: I think I'm completely unqualified to say what other artists treat sexuality in the same way as me, so the answer to that question is probably "no."

Collins: Whether or not you have, I was wondering if you feel depicting sex this way is more or less of a risk than the other approaches that are out there.

Gfrörer: Can you explain what you mean by "risk"? A risk of what?

Collins: You're right, that was a weird way to put it. I think what I meant by "risk" was the risk inherent in all the things one might usually associate with directly addressing sex and sexuality: self-exposure, putting your feelings and fetishes and desires and experiences out there in some way, making the audience uncomfortable, and so on.

Gfrörer: Okay, these are risks that I make a conscious choice not to consider when I write. Maybe the fact that I didn't understand your question at first is a sign that I've managed to convince myself those risks don't exist.

My audience's comfort level is really none of my concern, because I have no context to predict whether comfort or discomfort will occur in my audience as a result of my work. I said above that discomfort is part of my goal in making art, both for myself and for the reader, but I'm not, like, a guy trying to sell you a burger and saying, "Oh, people will relate more to this burger if we display it on a red surface, maybe with the sound of barking dogs in the background, that will help the audience to feel comfortable with the burger." I don't know. It would be a waste of energy to think about this for me.

As for my own vulnerability, I don't know how much you can really infer about me personally based on my comics. Every sex scene I write is based on an erotic spark that's compelling to me, certainly they contain elements of things that have actually happened to me, but there are layers of fiction obscuring them to the point where I'm not sure they're recognizable as descended from the source material. And anyway, I think it's important to have some earnest dialogue about negative emotions and sexuality, and if we're going to do that people are going to have to cop to thinking about it in the first place. So I'll gladly step forward to do that, whether it's risky or no.

Collins: I realized after I asked the question, and again after I explained it, that I was probably overselling the idea that the sex scenes are some kind of peek directly into your libido, and that therein lies the risk. That's not what I meant. I didn't really mean that by depicting this material so frankly that you were revealing personal information -- more that, as you say, these are freighted topics to begin with, and you're going about depicting them in an extra freighted way, and that's sort of a livewire to try to grab ahold of.

Gfrörer: Well, I like your characterization of something I do in my lap, listening to Rachel's, after my kid goes to bed as dangerous and exciting.

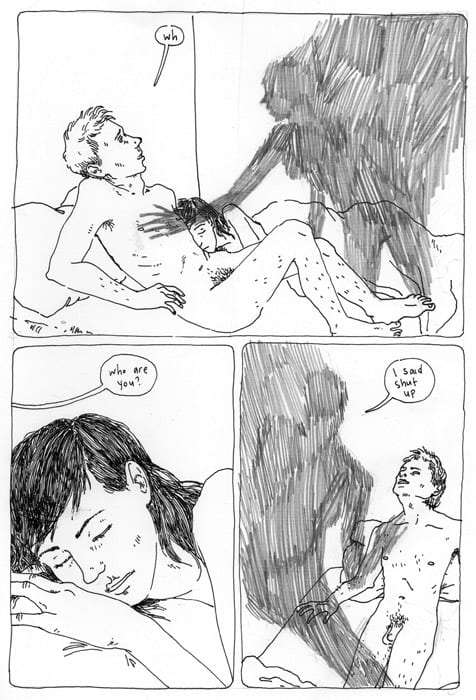

Collins: Glad I could help. I should also note that whatever their unpleasant emotional content, your sex scenes are in fact very sexy. The blunt, transactional nature of the handsome man masturbating on his late beloved's grave, the witch plucking the mandrake from the ground and inserting it into her vagina, and the shadow being telling the half-asleep young man "I just need your cum" all speak to the singlemindedness of the sex drive, a turning off of other concerns in the drive to get off that itself can be quite pleasurable. Maybe this is just gushing, but I was glad to see this kind of desire and arousal portrayed in a comic -- a willingness to acknowledge the separation of sex from external concerns.

Gfrörer: I'm surprised you get that from my work, because I'm often trying to write a freestanding sex scene and it's as if I've set a wet glass down on a piece of paper, and this puddle of context starts spreading out from it on all sides, before I know it the sex scene is padded with all this story that explains why it happened and what the fallout was. But I think maybe what you're responding to is that there's not a lot of guilt or justification around the sex in my books, I try to keep it morally neutral, or even ambivalent if possible. I don't particularly try to make my drawings seductive, except in the sense that something disturbing or repellent can also become alluring. The scene in Flesh and Bone where the man masturbates on the grave demonstrates this principle pretty well, I think. Is it romantic, is it disgusting? Kind of both, I guess? But I don't think he's driven by the simple desire to get off -- that scene is more analogous to the scene where the woman scratches her arm with a safety pin in Too Dark to See than anything. Like their emotions are so overwhelming that the mind dissociates, the physical act that reclaims the body is almost automatic. That moment where the mind and body are peeling apart is pretty compelling to me. Maybe that's what you're referring to.

Collins: It is. I suppose it's also worth bringing up that these sex scenes are taking place in what amount to horror stories. Sex and horror are frequently paired off like that; my favorite approach is probably the young Clive Barker's, because it was so utilitarian -- he needed an excuse to convincingly involve his characters in the "Jesus, what are you, crazy? Get the fuck away from that thing!"-type misadventures his stories required, and the stupid and/or amoral shit super-horny people frequently do fit the bill. You mentioned that frequently your stories evolve out of your sex scenes rather than the other way around, but regardless, do you feel they serve a concrete plot function in that kind of way?

Gfrörer: Well, every story has a thing that it's about (a guy being raped by a succubus, for example), and then a thing that it's really about (the entropy of love). Sexuality is important to show because it's a place where those two worlds, the subconscious and conscious worlds, come close and almost touch. We access normally hidden places within ourselves when we express our sexuality and it helps the story to cohere when we see the characters drift into the realm between light and shadow where sex occurs. I guess that's not so concrete but it is a valuable element of storytelling for me.

Collins: I'm really curious as to why you return to the supernatural as often as you have. It seems to me that you could quite easily strip away many of the supernatural elements from your stories and, after a little reshuffling, have perfectly good literary fiction -- literary fiction as a genre -- on your hands.

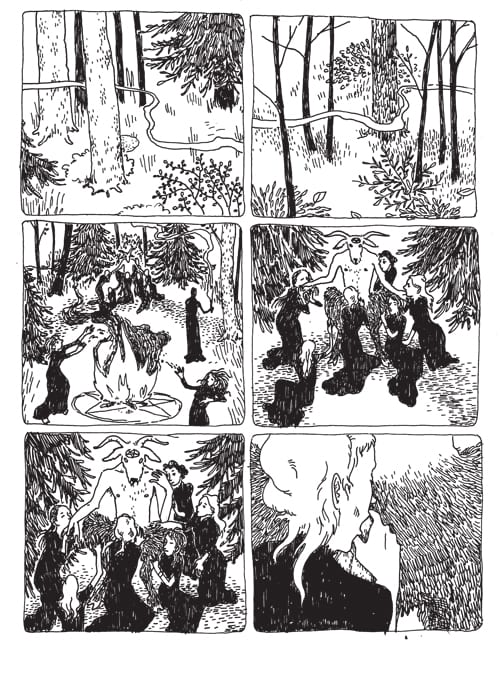

Gfrörer: It's interesting that you say that, because I try to write the supernatural events in my stories in such a way that if you removed them, the story would still make sense and could unfold in the same way. I mean, the mythology I'm drawing on developed to explain things for which there was no known explanation, but which had nonetheless occurred, and often that's the role magic plays in my work, when something inexplicable happens, the supernatural is there to take the credit.

But it wouldn't make such a good story if the supernatural elements were removed altogether. In Too Dark to See, what makes the argument between Lauren and Jamie so excruciating is that Lauren's fears are completely justified--he has been unfaithful to her, with devastating ramifications for them both, and neither of them knows it, we see them struggle to convince themselves it's not true, but we know it is true.

I think it would be a mistake to aggressively pursue phenomenal realism in fiction at the expense of emotional truth. Besides, it would be very boring for me to draw.

Collins: Hmmm. That's a really interesting way to put it. I'm often surprised by how emotionally natural a sudden burst of unreality can feel in a story otherwise concerned with realistic emotions and events. Without even going any farther afield for examples than comics that involve witchcraft and demons, you don't need to look any further than the witchy stuff that pops up in both Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez's work from time to time. I'm wondering if there's...I don't know, a mystery element to why we feel certain things so strongly that enables an artist to slip the supernatural into a realistic story and get away with it. Actually, bringing up Los Bros' horror stuff makes me wonder: Do you consider yourself a horror cartoonist? I do, although I'll admit to very broad standards for genre inclusion.

Gfrörer: Yes, I would like to be. It's my favorite genre. There are so many valuable intense experiences that only seem to be talked about in the context of horror stories. I try to make my books scary.

Collins: I was surprised to discover that you're a parent. Of course, I'm always surprised when people younger than I am are parents, though I shouldn't be because I know tons of them. But it seems like having a baby would hit you right in your creative wheelhouse, based on the images and ideas present in some of your comics. I know that for me, while I'm endlessly delighted by my baby herself, having her has made me even more pessimistic about living in the world. I look at her and see nothing but a happy little person with endless potential, then look around and am constantly reminded of how human behavior, the realities of illness and mortality, and simple bad luck is ready to crumple her up into a wad and toss her into a corner someplace. You told J.T. Dockery that motherhood made you more empathetic -- has it changed your concerns and goals as an artist in any other way?

Gfrörer: Well, maybe I should clarify that I was referring to the oxytocin high and resulting super-empathy that occurs during childbirth specifically, and it did wear off after awhile, which is how I was eventually able to watch those movies I talked about avoiding when my son was first born. But I've always been a pathetically emotionally sensitive person and that hasn't changed, and yes, it does inform my work. I've had the opportunity to experience a variety of new emotional extremes through parenting and that's all grist for the mill. I will avow that parenthood is functionally identical to having a Harkonnen heart plug installed.

Collins: Does your emotional sensitivity provide an alarm system for you, in the sense that when you hit upon something that upsets you personally, you realize it's worth pursuing artistically?

Gfrörer: That's a very accurate description of my process, yeah. The ideas that make me uncomfortable and upset, but that I keep returning to like I'm picking a scab, are the ideas that I know are worth developing into stories. I recently bookmarked this Metafilter comment on the subject of Piss Christ which gets at something I think about all the time: "With good art, that irritation you feel is the experience of being challenged -- of having a piece of art force you to confront your assumptions about art, or, as with Serrano's piece, puts a finger on societal fracture points -- areas where there is no consensus, and there are strong, unexamined feelings." I mean, I'm positively not capable of making a work of art as brilliant as Piss Christ, but those things to which I have an intense reaction that I can't definitively categorize or name, are the things I want to pursue.

Collins: Though the horror imagery you work with is striking and strong and imaginative -- the lion demon, the bird clawing out the child's eyes, the flayed little boy, the shadow people -- the most chilling elements to me were verbal. The demon telling the witch that love is just a meaningless diversion imposed on humanity by higher beings, that it's holding them back instead of elevating them, knocked me on my ass. So did the succubi not just taking advantage of the young couple, but mocking them, with a really catty and dead-on riff on young people using old-fashioned baby names, "hipster grandpa names." It was almost sickening, the cruelty of it. A lot of contemporary horror is effectively mute -- unstoppable slashers, mindless zombies, cryptic J-horror or Paranormal Activity ghosts and demons, huge semi-insectoid aliens gone amok. Even David Lynch tends to let the image do the talking. An articulate monster that mocks the horror it causes...that's a hard pill to swallow. What did you gain from their verbosity?

Gfrörer: The supernatural creatures in my stories aren't necessarily monsters. They don't always even function as antagonists. They're more like the Cenobites from Hellraiser than, say, the serial killer from Saw. I think it's essential that the audience has an opportunity to relate to these characters. Do you know the George Macdonald story "The Shadows"? The shadow people in that story consider it their responsibility to frighten people by acting out their sins on the dark walls, nudging them into better behavior. Then the shadows get together at the north pole and compare notes. And they sing a little song that goes, in part,

Dancing now like demons;

Lying like the dead;

Gladly would we stop it,

And go down to bed!

But our work we still must do,

Shadow men, as well as you.

So they're explaining that though they may be ruthless or cruel, they're not malicious, they're just doing their jobs. That's what I'm trying to show when they talk. To paraphrase Ben Bova, there are no villains, only people doing their best to solve their problems.

Collins: Total gearshift: I love the way you draw people. You seem to have honed in on a skinny physicality in your figure work that favors your wiry line, and your body language is as interesting to me in its angularity as Tim Hensley's. As a non-artist I have a hard time articulating a question based on this -- I guess I want to know what appeals to you about these kinds of human forms.

Gfrörer: Honestly, I don't do that on purpose and it's not a conscious formal decision. I can tell you that my very favorite-of-favorite artists are Kathe Kollwitz, Chloe Piene, Alice Neel, and Harry Clarke, and lanky vulnerable figures appear in their work as well, so I guess it must derive from them. I'm not really pleased that my work mostly depicts thin young straight white people, who already unfairly dominate the cultural dialogue, but that's the demographic to which I myself belong, so I have to admit it's my default. I'm working on it.

Collins: What tools do you use?

Gfrörer: I use a Pentel GraphGear 0.9mm mechanical pencil and a 0/.35mm Rapidograph technical pen, which is my magic feather. I also use watercolors, gouache, and Prismacolor pencils occasionally. I used to work at a paper store, so I tried out a lot of different kinds of card stock for drawing on and found that I like the results I get with matte or vellum finish inkjet printer photo card stock, so I buy that by the ream. When I'm working on a story I usually keep the pages in one of those 9"x12" portfolios with the clear sleeves, so I can flip through it and see how it flows.

Collins: I've only seen glimpses of your Ariadne auf Naxos series here and there, but it seems like there was a pretty substantial break between the more lighthearted literary gag strips of those comics and the really personal and unforgiving horror of Flesh and Bone and Too Dark to See. Am I getting that right? What changed? Or are you simply carving out separate outlets for different tones you want to strike?

Gfrörer: Ariadne auf Naxos is pretty dark, actually, but the drawings are simplified and the timing is controlled to emphasize the ridiculous parts, so it is more funny than my longer horror comics. My previous minicomics, The Anthology of Doubt, How Life Became Unbearable, and Venus in Blue Jeans/Venus in Furs, are characterized by the same gallows humor, self-inclusion, and scribbly kamikaze-style drawings. For most of my life I was ashamed that my personality is largely melancholy, masochistic, and severe. People are always telling me to lighten up and get over myself, and I know that sometimes I need to, which is why I do some funny comics. But as I get older I've gained the confidence to tell those jackasses to go fuck themselves when necessary, which is how I've managed to do some more serious work as well. The Ariadne auf Naxos series is still in progress, Tim of Teenage Dinosaur and I are working on publishing volume four within the next month or two.

Sorry about how you keep asking me questions about my work and I keep just talking about my inner life. Maybe later I can tell you about some dreams I had and how I feel about all the things. Oh, too late.

Collins: [Laughs] Oh dear, we certainly wouldn't want an interview about your work to deal with your inner life! I'm actually surprised you'd consider them separate things to begin with.

Gfrörer: Well, you don't really need your taxi driver to be lecturing you about his dreams when he drives his taxi. Maybe you just want to get to the airport or whatever. I mean, I put a lot of myself into my art, but it is a product that I'm producing because I'm a craftsperson, it is a separate entity from my essential self. But you're right that it's not always easy to make that distinction.