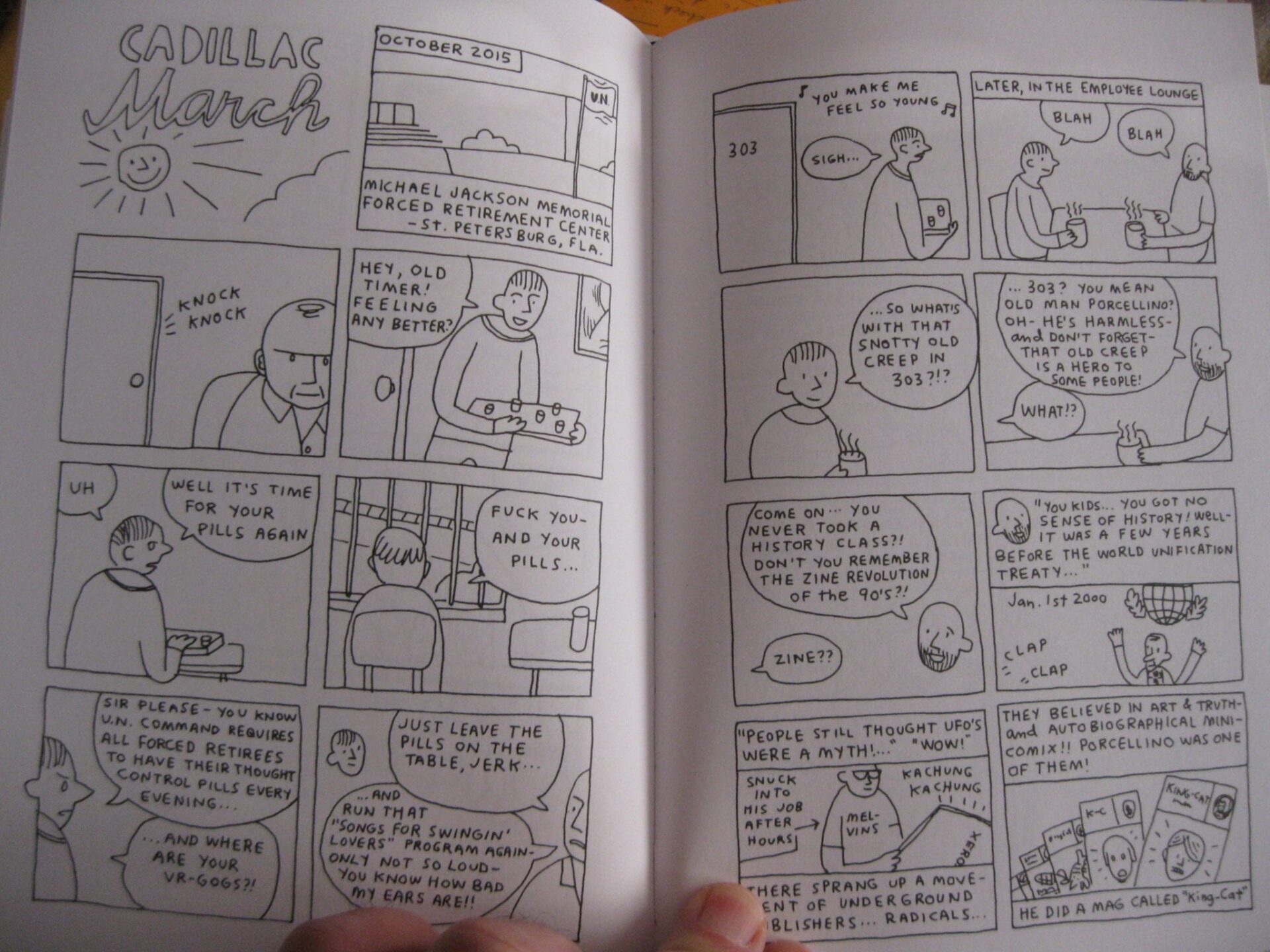

When I first approached John Porcellino to do an interview back in 2012, he said that he really wanted to talk about his work. None of his previous interviews had ever simply zeroed in on the actual content of his long-running King-Cat zine. Now that his latest collection, From Lone Mountain, has been released, I thought it was time to finally conduct that interview. Since releasing the collection Map Of My Heart, Porcellino has been open about the ways in which mental health issues, particularly Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), have impacted his work and his life. This interview covers the entirety of his career, from King-Cat #1 to King Cat #77, assorted side projects, as well as tangents into other areas. Knowing that we had a chance to do something special in this interview, I was grateful for not only John's time, but the thoughtful way he considered each question.

Photo by Phoebe Gloeckner

Early Years

The Comics Journal: How old were you when you started reading comics? What were you reading?

John Porcellino: The first comic book I read was Chamber of Chills #15, which had a cover date of March 1975, so I would have been six years old. This was at a time when people still bought comic books off a newsstand -- in my case, when we’d take the train downtown, my mom would occasionally buy me a comic at the Jefferson Park station. I only had a handful of comics growing up, like six or seven maybe, mostly weird monster comics. I had that issue of Chamber of Chills, a Creepy Things. That’s what I was drawn towards, as a fan of Svengoolie on TV: monster comics, supernatural stories. I had a Flash comic. I had a Superman comic from 1976 where someone punches Superman so hard he goes back in time to 1776 for the Bicentennial. But I had no sense of comics as a thing, as continuing stories with characters etc. I knew who Superman was, but I didn’t know there was a Superman comic that came out every month you could buy. It was just completely random, whatever happened to be on the stand when my mom happened to let me get a comic.

I did however, devour newspaper comics. I devoured the newspaper as a whole. I was a kid who was always reading. My dad brought home the Sun-Times every evening, and I would read it all, from the comics to the editorials, to the amazing advertisements. I loved the movie ads, although we never went to the movies, aside from occasional trips to the Will Rogers theater to see the latest Disney flick.

I did however, devour newspaper comics. I devoured the newspaper as a whole. I was a kid who was always reading. My dad brought home the Sun-Times every evening, and I would read it all, from the comics to the editorials, to the amazing advertisements. I loved the movie ads, although we never went to the movies, aside from occasional trips to the Will Rogers theater to see the latest Disney flick.

In Chicago you had the granddaddy of newspapers, the Tribune, which was around forever and had all the classic comics like Peanuts, Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Li’l Abner. The Sun-Times was younger and consequently ran stuff like Momma, Ziggy, Funky Winkerbean, so that’s the kind of stuff I read.

My grandma got the Trib on Sundays, so we would go over there on the weekends and I would read the color Peanuts and all that. So I only knew Charlie Brown from the Sunday strip and the TV specials. Later, my cousin had a collection of the Peanuts paperbacks, and I would borrow those. None of it was connected though, it was all just random impulses coming at me.

Did you grow up reading comics with others, like friends or your sister? Did you grow up drawing with anyone else?

I had only a couple close friends when I was a kid. The neighborhood crew would be outside every day. We’d play baseball every day in summer and football every day in winter. Then we would go home to our respective houses, and that’s where I read. Again, not many comics. But I always had a huge stack of library books next to my bed. I still do today. I just read voraciously.

My sister and I would sit at the coffee table and draw. I remember we had these early computer printer pages, like these enormous ledger-sized pieces of paper with obscure data printed on the back, folded with perforations along the long edge. My grandma must have brought them home for us -- she worked at a bank. We would draw on the back of those.

The first drawing I can really remember drawing… my family had taken a vacation to St. Louis, and I was in awe of all the bridges where the highway crosses the Mississippi, like a spaghetti noodle bowl full of criss-crossing bridges and overpasses and underpasses. My friend Robert and my sister and I decided to have an art contest, we would each draw a picture and then vote on whose was best. I drew an image of those crazy bridges. I was sure I would win the contest. I must have been drawing for awhile, I was pretty confident! My sister ended up winning the vote. I was crushed and bewildered! Ha ha.

You've written very little about your early childhood. Why is that?

Hmm… I guess I never thought about it. I feel like I’ve done some comics about that time. Maybe they didn’t make it into the collections. In the mid-2000s I drew a long comic called “Last Days at the Old House” that kind of goes into those days growing up in Chicago. I never inked it though. It’s like 75 pages. Eventually I’ll finish it and publish it. I have a book in mind called Exploring that would collect that story and a few others about growing up.

In some ways I look at my childhood as pretty idyllic. I read a lot, played with my friends. There were only a few really traumatic things I can recall, not a lot of drama. I mean, I think there was drama, but maybe I was just too young for it to register consciously.

Were you encouraged to draw or play music as a child or teen?

No, not at all. I mean, when I was a kid, we’d sit around and draw. Now that I think about it… my teacher in 5th grade, Sister Rita Mary, strung an acoustic guitar for me, and I remember bashing on it while sitting on my bed, yelling a song about the Cubs. Till I broke a string, and I don’t remember ever picking it up again. As a teenager I was actively encouraged not to draw. It’s a thing that’s fucked me up to this day. I drew constantly, wrote stories, but that activity was discouraged. It was considered inappropriate. When I was in high school, and it became more serious, where every elective course I could take was an art course, my parents really started to get worried. Art was not something that respectable people did. It’s not like they forbid me, but it was a major source of friction.

There was the usual worry of how would I make a living, how would I take care of myself, support myself, but it also went further than that. I don’t know if it was a midwestern thing, or something more specific to my immediate family. But my whole life I’ve struggled to overcome the voice in my head that tells me what I do is unacceptable.

Has that voice of parental disapproval ever been something that actually spurred you to do art? Like a rebellion thing?

Well, I don’t know. I want to say no, but these things are so complex. I do remember once when I was in college -- I was a painting major. I was doing comics, and playing in a band, and writing poetry, but my “day job” was painting. I had two very influential teachers in college. The first guy, John Rooney, he was very traditional in a lot of ways. He emphasized hard work, observation, refinement -- even if the end product was very rough and raw. I had a lot of psychological problems in college, and a lot of struggle with my notion of wanting to be an artist and what that meant politically, having come out of punk.

Over time my college work became more and more “anti-art.” I was pulling fine art apart by the seams. My work got messier and less art-like, much to Rooney’s chagrin. He hated where I was going with my art. I think he had viewed me a bit as having taken me under his wing, and he saw my new direction as a repudiation of that. It was a very weird parent/child relationship. I remember one day I had a devastating critique with him, he was withering in his criticism, and I had plans that night to drive into Chicago and print the new Cehsoikoe at the Kinko’s where my friend Lainie ran the night shift. And I remember actually thinking, “While you’re in bed, you old man, I’m going to be driving through the city at night to covertly print my zine.” Looking back on it now, what a terrible thing, but the point is I had that kind of thing inside me. I don’t know that I could ever consciously take it out on my parents. Poor old Rooney bore the brunt of it.

When you started drawing as an adult, was there any style in particular you were emulating?

By adult, I would say my high school years, when I started to become very serious about making art… I came across a couple enormous influences. When I was a freshman I had a wonderful, hip young art teacher -- she turned me on to the Hairy Who, the Chicago Imagists. At the same time I started reading the Chicago Reader, which is the local weekly alternative newspaper. My dad would bring them home for me every week, and again I’d read them cover to cover. Everything, the articles, the music and film reviews, I even read the classifieds!

The Hairy Who Slideshow (1967) Chicago: Hyde Park Art Center

The Hairy Who Slideshow (1967) Chicago: Hyde Park Art Center

In the back with the classified ads, they ran a few comics. There was Matt Groening’s Life in Hell, Lynda Barry’s Ernie Pook, and a few others. Those two strips blew my mind open.

Let's unpack that a bit. What was it in particular about those two strips that made them have such an impact? Was it the drawing? The humane and heart-rending stories by Barry that were frequently poetic? The nasty cynicism of Groening?

Yeah, I suppose all that. I mean, I had the good luck that my first two inspirations in comics were these geniuses, right? I loved the scratchiness of Lynda’s work, and her goofy humor that unexpectedly led to real poignance. With Matt Groening, there was that line. Not to mention the punk snottiness, the middle-fingeredness of it all. I mean, I certainly drew from those guys aesthetically. In some ways maybe my comics are some weird amalgamation of their two styles. But I think even more it was, “Oh, comics can do this and this and this.” They can do anything.

I had been drawing comics for a while. My grandma had a fascinating collection of paperback books in her basement that I would take home and read. Kind of the paperback pop culture classics of the time, and earlier. Like I read all the dystopian literature at a real young age -- 1984, Animal Farm, Brave New World. She had all the Ian Fleming James Bond paperbacks with the awesome covers, and I got obsessed. In the late '70s I created a character called James Bombed, and would fill up lined notebooks with comics about his adventures. Later I drew a silly Dungeons & Dragons comic called Tales of Hogarth the Barbarian Pig. This was the first comic or story of mine that I shared with my friends. I drew it on folded typing paper, like a digest-sized zine, and when I was done my dad would take the pages downtown and photocopy them at his office for me. Then I would hand copies out to my friends at school.

So I was making comics a bit here and there -- but when I found Matt and Lynda’s comics, my brain opened to the possibilities. So that’s a long-winded way of saying they were my major influences as an adult, or young adult. I didn’t really try to emulate them so much -- though I did a number of drawings in a hybrid Lynda Barry/Jim Nutt style. More that they showed me a way of making art through comics. Them and the Imagists.

The Distributor

What pushed you to create your distribution service, Spit and a Half?

After college graduation I was working in a warehouse in DeKalb, driving a forklift, running a glass assembly machine, and drawing my comics at night. This was my parents’ goal for me -- work an honest job, earn a respectable living, and if there was time left over, then you could do your drawings. This mentality was so ingrained in me, it was almost like I had unconsciously acquiesced to it. But increasingly I began to realize how much time and emotional energy I was expending trying to fit into a straight world that I had no real place in. I began to wonder what I could accomplish if I found a way to put that energy into something more personally satisfying. One day Henry Rollins came through town to give one of his spoken word things at NIU. I was kind of beyond my Black Flag days, but I thought I’d be remiss not to go see Henry Rollins speak in my town. So I went, and his talk was absolutely inspiring. Not so much what he spoke about, although that was great, too… but that I looked at this dude and was like, “He’s doing exactly what he wants to do, the way he wants to do it.” He’s going around the country talking. It was his independence that inspired me.

Around the same time my good friend Donal had moved to Denver, on a job transfer. He was bugging me to come out and visit with an eye to moving there. He regaled me with stories about how beautiful the city was and most of all, how cheap. In the spring of 1992 I flew out there for a few days, and when I came back I gave notice at my job and made plans to move.

I had been inspired by the movement that was to become “indie rock.” This was a movement of people who came out of punk, but pushed at its boundaries, made it broader, more open and inclusive. Specifically, I found the K Records catalog, and then the Ajax catalog out of Chicago. These were mail-order companies for small label or self-released underground, uncompromising music. It occurred to me that I could do a similar kind of thing with zines and comics. I had enough friends making good comics to pull them all together, put them in one place, and start selling them through the mail. So I moved to Denver, where rent was $175 a month, and put out the first catalog.

Do you get a sense of the influence and importance of Spit and a Half? Rob Kirby noted that you were the first straight person to distribute his comics, for example, creating an important crossover. You've undoubtedly introduced so many readers to comics they might otherwise have never seen; does this give you satisfaction as a distributor?

Absolutely. It’s the reason I do it. I always got a huge kick out of bringing disparate voices together. To me the thrill was finding comics that seemed quite different on the surface maybe, but within them there was this running thread I sensed -- of independence, idiosyncrasy, autonomy. Like punk, these were people doing what they wanted to do, the way they wanted to do it. There was an authenticity to it that inspired me.

I was an oddball, a weirdo, all my life, and it caused me a great deal of pain, but it also brought me the great joy that comes with discovering oneself. I wanted the distro to be a home to other people like that, and I think it happened. Artists found each other through the catalog, became friends, peers. The inclusiveness I mentioned up above that I found in indie rock is what I was after. The Spit and a Half tagline at the time was “Girl, Queer, Freak Friendly -- since 1992.” Together we were trying to create a different, autonomous, inclusive world.

The Publisher

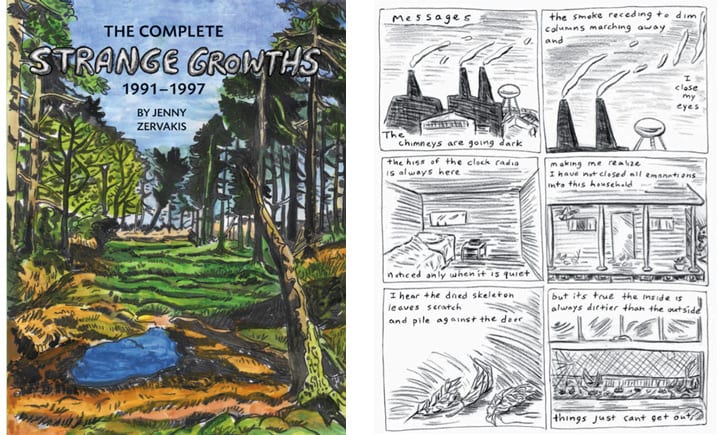

You've noted that you had been planning to publish a collection of Jenny Zervakis's work for years but that those plans were curtailed by illness. Aside from her work being so in sync with yours, was the driving force similar to earlier motives: wanting to get something beautiful but hard to find into the hands of new readers?

Yes. In early ‘97 I’d been running the distro for five years, and there were a few favorite artists whose work I always had a hard time keeping in stock -- specifically, Jenny Z., Tom Hart, and Jeff Zenick. So eventually I just asked them to send me Xerox masters, and I used those to print their zines myself in Denver. I’d print on the back, “Manufactured and Distributed by Spit and a Half.” You know, we were selling these things at the time for a buck. I had the idea of putting together booklets that were a little bit nicer than the average zine, but not really a book -- a bit thicker, better paper, not huge, but like 52 pages -- The Best of Strange Growths, The Collected You Come Too, etc. Maybe two-color covers on a nice quality cover stock. Something that you could honestly put a $3 price tag on and still respect yourself in the morning.

So what happened was, as I made these plans, I ended up getting very sick... for about a decade. Not only were my publishing ideas put on hold, but I even had to close the distro. Then, twenty years later, in regards to Jenny’s book, it occurred to me that the time was right again to do something with it. As for my motivations-- if nothing else, I selfishly just wanted the book to exist, and it seemed like if that was going to happen I would have to be the one to do it. And of course, I love Jenny’s comics. She was such an integral part of our scene in the '90s, and for various reasons I felt like she had become unknown to cartoonists and readers nowadays. My hope for the book was twofold -- to make something for all her longtime fans, from back in the day, but also to make her work available again to the new generations of comics readers. Her work was truly groundbreaking and beautiful, and a lot of that history from the '90s has gone undocumented. I wanted to correct that in some small way.

How many did you publish, and how many have you sold?

I printed 1000 copies and have sold about a third of that in the first six months since it debuted. Which is great. The book has already reached a lot of those people I was hoping it would.

THE WORKS

Perfect Example

After doing King-Cat for nearly a decade, what led you to reprinting the material for Perfect Example? Was this driven by Tom Devlin and Highwater Books, or did you approach him first?

In ‘97, ‘98 I’d published the "Perfect Example" story as two consecutive issues of King-Cat, and about the same time Tom had started up Highwater. People were beginning to bandy about this notion of a “graphic novel,” and making book-form comics. It occurred to me that this story I had just made might work in that format. In one of my very rare moments of gumption, I asked Tom if he would be willing to publish it as a book, and he said yes… He’d been a big supporter of King-Cat through his position at Million Year Picnic. He even brought me out to do my very first signing, at MYP, in 1996, with Sam Henderson and James Kochalka. So it felt natural to work with him.

Did you have a sense that you were part of a wave of creators when you were first published by Highwater? You were obviously trading zines with many other cartoonists at the time, how did you view yourselves differently from past generations of cartoonists?

By the time that things like Highwater, or Black Eye in Montréal, were starting up, it was clear that there was a groundswell of really talented cartoonists coming from the self-publishing movement. Professional comics had mostly ignored us, and large portions of traditional comics readership actively dismissed us (“If something is self-published it’s because it’s not good enough for a ‘real’ publisher to touch it…”), but there came a point where anyone who was really digging into comics as an art form had to start to take us seriously. We were photocopying comics that were as good or better than the comics coming from the publishers. It happened in dribs and drabs. Slave Labor started publishing Jeff Levine’s Destroy All Comics. That was huge. You had a magazine on the stands that not only took self-published comics seriously, but put people like me or Tom Hart on the cover! I remember The Comics Journal published something like a “Young Cartoonists Issue”, with a lot of us self-publishers profiled. That was huge. TCJ reviewed King-Cat 50, a serious, thoughtful review. SPX had started up. Highwater, Black Eye began publishing people like Megan Kelso, James Kochalka, in tasteful, respectful ways. Top Shelf started up.

I can’t speak for everybody, but for me, I think we were the comics equivalent of punk, or indie rock. We were doing things our own way in a completely independent manner. It didn’t matter if a publisher wouldn’t sign you, because we had built a whole network of artists, readers, and distribution that bypassed the traditional comics publishing world. And many of us purposely chose to stay underground, to work within that system we had built, and grow it.

For me, I didn’t think of myself, as a cartoonist, as much different than previous generations, aside from that stuff I just mentioned. It was a natural progression from what people like Clowes and Bagge and Los Bros were doing. Add in that zine aspect, and a willingness to ignore or defy traditional comic book notions of “quality” or “professionalism,” and you have our generation. It was punk. You didn’t have to have traditional comics chops to tell your story, in fact your lack of chops only meant you developed in different, unexpected ways. That’s why that stuff was so fresh. It took a left turn.

All of your themes are front and center in Perfect Example: depression, anxiety, the search for beauty in others and in nature, the difficulty of being present and intentional. Looking back, how do you contextualize this piece in relation to your other comics?

It was important for me. That "Perfect Example" story was one I had worked on for many years, in different ways and formats. The first time I tried to put that story down in tangible form was the fall after it happened, in 1986. I had gone to college to study painting, I was making zines, writing poetry, playing in a band. I started to develop the "Perfect Example" narrative as a series of paintings, but it never went anywhere. I don’t think I had the perspective yet to tell it. It was the kind of thing, I knew it was an important story for me, and every few years I’d pull it back out and work on it a bit more. At one time it was going to be a series of prints, and then a series of magazines. And eventually of course I ended up focusing on comics.

I’d done the “Belmont Harbor” story for King-Cat 47. That was something like eighteen pages. By far the longest story I’d attempted, and it inspired me to try something even bigger, more complex. And that’s when I pulled the "Perfect Example" narrative out again. By this time though I’d figured out a way to tell stories, I’d developed enough as a cartoonist and a writer that I felt maybe I could do it justice at last.

It was a very different process. Most of my comics up to that point were pretty spontaneous, seat of the pants kind of endeavors. For Perfect Example, I wrote out the story once, wrote it out again, a third time, kept refining it. Moving elements around. I interviewed my friends about that time period, really thought about it, kept wrestling with it. It was a challenge.

At the time of publication, the story drew quite a reaction, especially with regard to your honesty about feeling suicidal and your depression as a teen. What did that feedback mean to you at that time?

It just felt good to me that it had touched people. That was our only goal back then: try to make good comics, and then get them into the hands of people who might enjoy them. To be honest, I don’t think I knew much about the reaction to it outside my immediate little circle.

Are you still in touch with any of the people you were friends with at the time who appeared in the story? What was their reaction?

For the most part, yes I’m still in touch with people. There are a few who I’m not really anymore. I think a couple people were hurt by it, or bothered by it. That was something I was sensitive to as I was writing it. In fact, all the interviews I did with people in preparation for the book came about because I wanted to contact everyone and-- not get their permission-- but to let them know I was drawing this story, and give them the option of having a pseudonym. Nobody asked for a pseudonym, and I assumed that meant they were cool with it, and I kind of assumed, “Everybody in the story knows what happened, knows what the truth is, and that’s what I’m going to draw. It will be fine.” The thing I didn't know until later is that everyone has their own individual perspective on what the “truth” is. I kind of started to learn that when I interviewed people and they had completely different recollections of certain events, or different reactions to things than I did. I started to realize that there’s not some kind of objective, perfect “truth” out there when it comes to these kind of things. In a way, it freed me up as an artist. Prior to that I really tried to be more journalistically objective in my storytelling. I took pride in making these things “true stories.” After Perfect Example, my attitude about that changed or my horizons expanded. I allowed myself certain artistic liberties, and instead of striving for some kind of journalistic truth, I began striving more to honor the truth of the story.

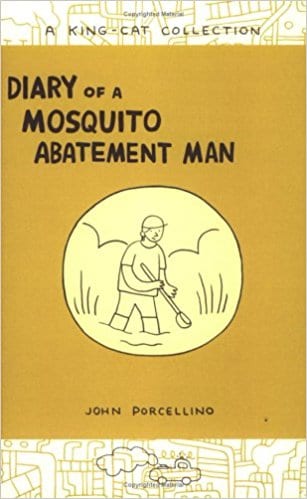

Diary Of A Mosquito Abatement Man

Your style underwent a dramatic change from the beginning of your career to your more mature style. What led you to decide to strip down your individual images?

It was never a conscious choice or decision, it was just how things organically developed. That was something that I emphasized to myself from the beginning of King-Cat -- I wanted it to be what it wanted to be. I didn't want to have a preconceived notion of what my comics, my zine, should be. I tried to get out of the way of my creativity, to allow what was inside to come out unobstructed.

Always, I saw the comics in my head and tried to put that down on paper as accurately as I could. Over time, the way I saw them in my head changed. They became pared down, I tried to let go of lines that were inessential. At some point when I was drawing a night scene it became redundant to me to fill in that black night sky with ink. It was already night, night is dark, why do I have to draw it? That black sky was inherent in the act of drawing “night.”

Why do you think the way you saw the comics in your head change? Why did they become pared down?

Why do you think the way you saw the comics in your head change? Why did they become pared down?

Aside from my early and long-lasting interest in the band Yes, I’ve always been attracted to art -- whether it was painting, writing, music, film-- that was spare, that emphasized the gaps in things, the empty spaces. Even like punk rock -- it’s “three chords and the truth,” right? You break things down to their essence, to see what’s really there below all the layers of thinking or artifice, or simply unnecessary stuff. It’s getting to the heart of the matter in an aesthetic way. So I think it’s natural that my own art began to take that route. It wasn't anything I thought about consciously at the time, it was just that was felt “right” to me was evolving.

Was a change of tools involved?

Now that you mention it, there may have been a change of materials involved.

When I started King-Cat, I had a set of Rapidographs I had to buy for my college design course. I used those to draw my comics, on cheap pads of notepaper I took from my dad’s office. They were those pads that he had printed at the top, “From the Desk of Charles Porcellino.” They were exactly 8.5” x 5.5”, the size of a digest zine page. So I took those and drew on the back. The ink bled, blobbed, the metal Rapido nibs caught on the scratchy paper and skipped, dragged. At the same time I was intentionally drawing quick, without thought, no editing. So naturally the comics were rough. Later, those blobs and scratches started bothering me… as the line refined itself, I was looking for something smoother, less drag. I started drawing on laser paper, which was better for those purposes, and then Microns came out and on laser paper they were like butter! That combo allowed me to draw very smoothly, less hiccups in the line. I started to get off on making the most graceful arcs I could with the line. The drawing itself started to become about that line... But again, it wasn’t deliberate in the sense that I chose to change my style. It just naturally evolved, I followed it where it took me.

In many ways, this comic is the introduction to your exploration of Zen Buddhism. How has your connection with Zen evolved since you wrote this book?

Zen is the study and understanding of everyday life. So Zen is happening all the time. It’s a matter of becoming aware of it. The more you practice, the more slippery the line between practice and everyday life becomes. At some point it is just Zen.

There are many ways in which your comic is the work of a nature observer, seeking to gain knowledge out in the field of things that are hidden. What is it about those experiences that leads you to want to record them? The "Asparagus" strip is a good example of this kind of simple beauty and new knowledge.

I can’t really explain why one experience becomes a comic, and another doesn’t. It’s just intuition. Something will happen, and usually I’ll know right away, “That’s a comic.” I think a lot of the time the impulse for my comics comes from a moment of transcendence in life, when borders break down and a kind of unity comes over the scene. That mysterious and beautiful feeling is something I’ve felt on occasion my whole life, from the time I was very little, from the time of my earliest memories -- the feeling that there is something beyond this world of the senses, that can somehow mysteriously and unexpectedly be apprehended, that goes beyond words or description. Those moments, trying to understand them, have been my primary motivation in life. I like sharing them. My hope is that it encourages people to look within themselves.

Your comics do not shy away from despair, disease, depression, and the forces that assail us in life. Yet they also seem deliberately life-affirming much of the time, as you share what it's like to be human, even in the darkest moments. Is there an intentionality in that life-affirming quality, or is it simply a byproduct of your exploration of the world?

In terms of exploration, I do think it’s only natural that the more you look into something, the more it opens itself up to you, maybe you can come to an understanding that wasn't there before. I’m interested in real life -- whatever it is at any given moment. Real life is sometimes blissful, extraordinary, and sometimes it’s brutally painful, or simply boring. My goal as an artist has been to depict that experience, in all its various forms, with open eyes. As for that life-affirming quality -- I do want to have a positive impact on the world. I’m not going to sugarcoat things, or hide reality under a pile of flowers -- but I do want to give hope and comfort to people. Maybe more truthfully, I want to encourage people to find hope and comfort in their own lives.

I remain haunted by the chemical plant chapter. Do you recall how long you were in that complex? Did you ever return?

I remain haunted by the chemical plant chapter. Do you recall how long you were in that complex? Did you ever return?

No, I never did. Usually you return to mosquito sites again and again. That one might have been a special contract job, I don’t remember. But I'll never forget that experience, truly one of the most surreal moments of my life. It was I think a combination of the slowness of the spray rig, where everything already feels slow motion and otherworldly, and the wholly artificial light, illuminating everything with the same dead, inescapable glow, and the dull hum of the equipment, and just the overwhelmingly complicated, absurd hubris of man.

SPORTS

You've written a little about sports as a background element for most of your career. Did you gain your Chicago sports fandom through your dad?

It was through my dad. My dad worked a lot. Oftentimes, I was in bed by the time he got home from the office. So weekends were dad time. And Sundays in Chicago mean Bears. So I would watch the games with him. It was a way of being close to him, to have something to do together.

What did rooting for a team mean to you? Was it personally important to you? What did you get out of the experience?

It was personally important to me because it was personally important to my dad. And with the Bears, aside from the years around the Super Bowl run, they were usually dismal. So you take a kind of hangdog pride in a team like that. There’s always next year. Same with the Cubs.

The Cubs were different. My dad didn't care about baseball. Baseball was something I did with my friends, especially my friend Robert who lived down the block. Every summer day consisted of me going over to his house to watch the game.We’d sit on his back porch with the TV on. We had a bowl of stale popcorn up on the top of the fridge and we’d take it down and watch the game. Every day we’d make a new bowl of popcorn and put it up on the fridge and take the previous day’s one down, because day-old popcorn is better than fresh.

The Cubs — I kind of gave up hope after a while. When they blew the postseason in 2008, that was kind of the final straw. I thought it was going to be this cosmic thing, that they were gonna go to the World Series exactly one hundred years after the last time they won, and win it. So when they totally choked in the first round of the playoffs, I decided I would no longer emotionally invest in this team. Then I moved back here right around the time the club started to get serious about turning things around. I still can’t believe they won the World Series. I never thought I would live to see it. So many Cubs fans didn’t. That’s what got me. The people who lived their entire long lives as Cubs fans and didn’t live to see them do it.

Was it ever uncomfortable writing stories about punks with one eye on what the pro jocks do?

My punk years and years as a sports fan were pretty well separated. Even ‘85, the Super Bowl year, I kind of had one eye on it and the other eye was rolling a bit, like, “Sports, duh.” I was a surly teenager.

For many years after that sports meant nothing to me. It wasn’t till I got to Denver in the early '90s, right about the time [Mike] Shanahan took over as coach, that I got back into it. I started watching the Broncos and got super into it. And of course the Bulls of that era. You had to watch. It was like watching ballet, some kind of pure art. And I’ve followed sports ever since.

Has your sports fandom significantly diminished, especially given the corruption of the NFL?

I absolutely hate the NFL. This year I successfully not-watched most of the Bears games. I watched a few, and I watched a couple playoff games. I hate just about everything about it. The stupid end zone dances, the histrionic poses after a simple tackle, the “what is a catch” bullshit, Deflategate, the absolutely inexcusably bad refereeing, the pass interference-based offense... The military-industrial horseshit. What other game starts off with billion dollar instruments of death flying over the stadium? Not to mention that it seems like half the players are wife beaters, drug dealers, or murderers. It’s a game that’s hard to root for. Nowadays I’m more into hockey.

King-Cat Classix

“Volume 1”, # 1-30

First, a general question about this volume. You had printed minicomics versions of King Cat collections before, but nothing on this scale. Was it important to you as a creator to see your work back in print and remain in print in this form?

First, a general question about this volume. You had printed minicomics versions of King Cat collections before, but nothing on this scale. Was it important to you as a creator to see your work back in print and remain in print in this form?

My idea with the King-Cat Classix zines — there were four of them — is that after every ten issues of the zine I would let those go out of print and collect the “best of” those strips in a volume of KC Classix. So Volume One collected stuff from issues 1 through 10 and so on. There should have been a Volume Five after issue #50, but by that time I was having health problems, my focus was elsewhere. And then I moved back to Chicago and everything became more complicated and expensive, and I lost my trustworthy, affordable printer back in Denver. Everything just became harder.

If it hadn’t been for the book, and for my starting to work with D+Q, I’m sure eventually I would have found a way to collect this stuff. All my work is of a whole. The more of it you read, the more you can understand it, the more the stories, characters, small events, patterns, coalesce into the bigger picture, which was always my intention with the work. So yes, it’s important to me to keep these stories in print.

What has the process been like in annotating these comics? I recall that for Map of My Heart, you revealed a lot of personal information that really informed the original comics.

When I first put together the KC Classix book for D+Q, I struggled with whether to include the notes or not. It seemed pretty pretentious. And part of my work with King-Cat is intentionally letting the reader make connections, not necessarily spelling things out directly for them. But ultimately I felt like, if a favorite artist of mine published a book like that, I would love to read those notes, to get a little more insight from the artist themselves. So I bit the bullet and started writing the notes. Once I did, it became enjoyable for me to look back, recall little details, put them down on paper.

With Map of My Heart, which collects work from some of the hardest of my OCD years, it became apparent the notes would be crucial. These were stories where, because of my illness, I was compelled to get vaguer than vague, to navigate this stream of constant negative energy and still find a way to express myself. So many of the stories skirt the details of the events they’re based on, or poetically tiptoe through them. The notes were an opportunity for me to come out and directly address the underlying issues that led to these stories and their creation. It was a huge relief to finally open up about that stuff.

Was this another instance of approaching Tom Devlin to work on a project like this? At the time, I thought your style was a curious fit for the D&Q aesthetic, but it’s clear that Tom Devlin and Peggy Burns had a strong influence then, and clearly have taken D&Q in some different directions.

Well, that was the other instance of gumption in my so-called career. In the early 2000s the Highwater edition of Perfect Example had gone out of print, and I knew Tom didn’t have the resources to reprint it. I was living in San Francisco at the time and at APE a bunch of people encouraged me to talk to some publishers about reprinting the book. That took balls on my part. I’m not one to put myself out there like that, but I told myself it was a growing experience. I approached Chris Oliveros at APE and put the idea of reprinting PE in his head. A few weeks later he wrote to say that they weren’t at the time interested in doing a reprint, because they were in between book distributors, but they would be interested in doing King-Cat as a comic book series -- a comic-sized edition that was half new material and half reprints of older stuff.

I remember the turmoil I felt at the time, because that just wasn’t anything I was interested in. I already self-published K Cat as a series, and wasn’t about to give that up or mess with that. I remember standing in my bathroom in San Francisco at 3 AM, thinking, “Am I really going to say no to D+Q? This is the kind of thing cartoonists dream of all their life.” But I said no.

Later that year D+Q approached me again once they had their distribution problems worked out and agreed to reprint PE. So that was the first book we did together. In the intervening months I had arranged with Zak Sally to reprint the KC stuff in a series of books on La Mano. The first of the books would be Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man, and then the second would be a reprint of Perfect Example. So we were working on Abatement Man at La Mano when the D+Q offer came through. Both Zak and I agreed it would make more sense to let D+Q do Perfect Example and see what happened. So that’s how the ball started rolling.

Shortly after the Drawn and Quarterly edition of PE came out, if my chronology is correct, Tom Devlin officially started working at D+Q. I’m not sure of the behind the scenes workings, but I’m sure that Tom was instrumental in getting me situated with D+Q going forward. He’d been a huge supporter of mine since the early days. That said, I remember when I first spoke to Chris about PE at APE, he said he had considered approaching me about working with them earlier, but figured I was a hardcore self-publisher and I wouldn’t be interested… so there was that support as well, going back awhile.

When you put together King-Cat #1, did you have a particular model you were imitating in terms of pure construction of the zine: size, number of pages, etc?

No, I had nothing specific in mind. Later on, much later, I began to see King-Cat as the classic “comic book” format: a cover, a back cover, a note from the editor (“KC Snornose”), a letters column, 32 pages. But originally I had none of that in mind. I just wanted to make a zine that was all my own work, instead of a multi-artist anthology (like Cehsoikoe, or my high school zine Zo-Zo).

You noted that King-Cat #1-30 represented volume 1 of your series and #31 was the start of volume 2. Has there been a volume 3?

Volume 3 is Map of My Heart, Volume 4 is From Lone Mountain. Volume 5 will be called In Search of the Cuckoo Bird. When Zak and I first began talking about publishing King-Cat Classix on La Mano, my idea was to do a two-volume set. For financial reasons at D+Q we combined the two into the one hardcover. I was dividing the issues up into sets that made sense to me personally and aesthetically. Issue 30 was where the experimentation of the early issues culminated in the story “October”, which was a turning point for me. Then, issue 50, where the collection ends, was another turning point. The comics had become more refined, more poetic, I was shooting for something beyond straightforward storytelling, or rather beginning to develop more of that element of my comics, which had been there from early days (e.g., “Leaves” from issue 36, “October”, etc).

It’s interesting to see the differences and similarities in the two volumes. Right away in #1, you have a dream comic. What’s become different is that fewer of your dream comics later on were so pointedly connected to sex and anxiety regarding same. Did the dreams themselves actually shift later in life, or did you prefer to record different kinds of dreams?

At the time, all my creative work even outside comics was very dream-based. My paintings were based in large part on dreams, my poetry, my writing. I was very interested in the meanings and purpose of dreams. I had this belief that the experiences you had in a dream were, or could be, as profound as experiences you had in waking life. They could change you, they could of course reveal things to you. So that was a big focus of my work in general. I was a horny dude, obsessed with sexuality. Those things came out in my dreams. I’m a good midwestern boy, so in waking life maybe they were repressed a little more. Eventually maybe I learned to integrate those sides of myself and the dreams changed.

Your earlier works, as you note, are much cruder, and not just in terms of the drawing. They are angrier, sillier and more juvenile. There were even a few you chose not to include because they were embarrassing when you looked over them later in terms of the crudeness of some of the jokes. Why did you choose to edit yourself in this way for the collection?

Well, at the time I started King-Cat I was a 20-year-old drunken art student. I was playing in rock bands, staying out all night, doing drugs, drinking, fucking around 24/7. I came from punk rock, where not only is crudity acceptable, it’s encouraged. My creative heroes at the time were the Butthole Surfers and Flipper. It was all about noise, releasing your rage, fucking with people’s sensibilities. Sarcasm, weirdness, unpredictability. Over time, some of us at least, you just get tired of making fun of things all the time.

As for editing KC Classix, a lot of it just comes down to: the book is already 384 pages — you gotta cut some stuff out. At the time I made those comics I was woodshedding. I was throwing ink on paper and seeing what happened, experimenting. Some of it held up, and some of it failed. Not all of it necessarily needed to be preserved for posterity. Maybe someday it will all come out, when I’m older and care even less. But it’s not like every comic was some genius move I was proud of.

In the book I did include certain comics that are not the best, but maybe they were important to me somehow, or they presaged elements of my work that would later become more important or something. I tried to effect a balance, to show the development of things, but it wasn’t intended to be some whole, complete collection.

My favorite early dream comic was “Attack Of the Musk-Ox”. I loved how it encapsulated work anxiety, sex anxiety, a fear of death and aging, and resentment toward authority all in one package—plus it was funny. Your cartooning was light-hearted in this one as well; you note Playboy as an influence here. By that, did you mean the Playboy cartoons as well as the woman of your desire in the strip? How clearly do you remember the details of your dreams when you wake up and how much do you have to embellish them? Do you set out to remember your dreams before you go to sleep?

Over time I remembered my dreams less and less. That’s I think a result of Pyroluria, which is a metabolic disorder I have, and maybe just getting older. For about a decade, when I was really sick, I never dreamt at all, or at least never remembered my dreams. Maybe a couple times a year I’d remember them. So they became less a part of my comics. I suppose too I hedged a bit once autobio comics became a genre unto themselves and “dream comics” became one of the the “self-indulgent” things that people criticized autobio comics for. I can see their point sometimes. With my dream comics, I treated the dream comics the same way I treated the comics about my waking life. Not everything got put down on paper. The dreams I drew were ones that had significant impact or meaning to me, just like my other stories. But for a while they dropped off for me. Nowadays I’ve started to include a few more dream strips on occasion.

I never embellished my dream comics, just as I never embellished my waking comics. And I never messed around with lucid dreaming really. By the time I was aware of that stuff the pyroluria had kicked in. Anyhow, my whole life is lucid dreaming!

As for Playboy, I think my dad had one issue that I knew about. It was out in the open in our basement den, where his home office was. It had an article on divorce (he was a family lawyer who did mostly divorces and child custody disputes, extremely depressing stuff). It wasn’t till later when we moved to the suburbs and I started hanging around in the woods that I’d come across porn. Fascinating to me even at that early age, my tweens and early teens, was the simultaneous attraction of sexuality and the shame of it. That we lived in a society where men were inundated with sexual imagery and ideas, but then when you acquiesced to them you had to dispose of your indulgences out in the woods. You had to hide them under boards. You couldn't even throw them in the trash can because someone might see them there and trace them back to you!

As kids, we learned at some point the day every month that the 7-11 threw out their unsold mags. They’d tear them in half and throw them in the dumpster, and we’d dive in. You’d drive in your car and see porno mags disposed of on the side of the road. Eventually you grew to pinpoint the exact ratio of flesh tones to other colors that said “porn.” “That’s porn… that’s just a sales flyer…” It’s a twisted world. But porn wasn’t and isn’t as foundational to me as it is for other people. I was too Catholic or something.

“Art Party” is my favorite of your early autobio pieces. There are so many random, weird details, like walking out part way through Akira, your first reference in a comic to someone reading one of your comics (a reference to striking out with a girl, hilariously), the three testicles bet, and a key panel with a naturalistic drawing of your hand clasping that of one of the women at the party. There’s a warmth to this story, both toward the evening and those you met but also yourself. How were you able to recover story pieces during the periods when you were still drinking regularly/heavily?

I guess I had a pretty good memory, plus I was writing this stuff down, making comics about it immediately. There wasn’t any kind of delay. And despite my binge drinking, I don’t remember (haha) being blackout drunk too much. By the time of that story, "Art Party", I was playing in a popular band in town, I was making good paintings, making my comics. I was starting to develop the shadow of what someone might call self-confidence. I was part of a community. I talk about it a bit in the Root Hog or Die documentary… there was a supportive scene in DeKalb that I became part of. There was creativity all around, openness, acceptance. It didn’t last long before things started to tarnish, but for that brief period, we took the world in hand. I had dropped acid too, and that changed everything for me.

The "Violent Garden" stories were among the highlights of volume 1, because they are so ridiculous. The fact that you had a French subtitle for the story’s title spoke to the sense that you were parodying something that might have cultural cachet elsewhere, like in another country, but also seem completely absurd here. Did you ever want to do more of these strips than you did, or was it clear that this was something with a very short shelf life?

"The Violent Garden" was just a goof, but I remember getting pretty swept up in it. I think there was a foreign film that came out around the time by the same name. I copped it from that. It was a lark. It was exactly the correct number of episodes, it was just absurd. A kind of riff on trashy European art/sex movies or something. The idea was there were these characters you follow, but most of the episodes are missing. Sometimes they’re out of chronological order. It didn’t particularly make any narrative sense when you read it, so much was left out. But then it turns out that there is some kind of goofy story going on the whole time. I remember getting pretty excited as I was drawing the finale. Someone should make a Masterpiece Theatre out of it.

Was #18 the first issue to feature a “Top X” list? There was always a sense of balance in your comics—whenever there was a strip about anxiety or fear, the top 40 or 20 or whatever list was a counterbalance. Same with the strips about animals. This isn’t the work of a punk who is just bitching about everything, it’s about someone trying to enjoy the absurd lives we are given as best we can. Was this the message you were trying to send, even then?

Yes. Especially after I started taking LSD, it changed my whole sense of things, or maybe it brought that sense to the forefront. The sense that we are in an absurd and terrifying but also wonderful, joyous life, that all things are part of the whole. There is nothing to fear. There’s no division between things, between ourselves. That the sense of division is an illusion. Rather than absurdity being a source of anguish or uncertainty, by embracing it, that same absurdity can become a source of joy and cohesion, unity.

Back to your animal strips: there was the all-cat issue and strips like “Cat Rescue”, designed to look like a house as you describe climbing up to rescue a cat. This is a common occurrence to you; what is it about animals that have provided you with such a sense of empathy?

Well, animals are awesome. Maybe growing up feeling isolated and rejected, I turned to animals and their unconditional acceptance and appreciation.

"Captain Leopard, Rival Of The Mouse": provided by John Porcellino

"Captain Leopard, Rival Of The Mouse": provided by John Porcellino

“The Mouse” really does seem to be your alter-ego: constantly angry, belligerent toward others, aggressive, etc. in a way that you never are. In the notes, you talk about how you were surprised that you only ever did one story in King-Cat with this character, even though he was an “integral part of my comics brain.” Why did you do only the one story? What does this character mean to you?

Maybe you’re right, maybe the Mouse™ is my shadow self. He’s those parts of me that I won’t let people see. As for doing only that one story, maybe some things are just too perfect to mess with. Maybe that’s how I felt about the Mouse. He did make one more appearance, in a pin-up that was printed in one of the KC Classix zines, called “Six Pack of Justice”. It depicts him blacked out on the floor in a puddle, bottles and cans strewn around him.

He’s kind of like Racky Raccoon. He came at the perfect time and then went. I’m so different now I can’t go back and touch that place again. It’s gone. It would be a disservice to try to rekindle it. That said, a couple years ago I was doodling and drew a superhero called Captain Leopard, and instantly I was like, “He’s the Mouse’s nemesis. He’s a superhero too, but unlike the Mouse he’s not a fuck-up. He gets the job done, is well liked and respected, and thus the Mouse hates him with a passion.” So I still think about these things. The Mouse is still alive in my head, but he’s untouchable.

With Racky, at times over the years I’ve worked on a long story called “Racky Goes to Hollywood”, which is a satire of the comic book and entertainment industries, but I just don’t have the fangs to do that kind of work justice anymore.

“Well-Drawn Funnies”: it’s interesting to see this manifesto, where you talk about the Hairy Who, punk, ugliness in art, underground comics, etc. The funny thing about this is that your art was about to go through a transformation, staying spare but looking beautiful.

“Well-Drawn Funnies”: it’s interesting to see this manifesto, where you talk about the Hairy Who, punk, ugliness in art, underground comics, etc. The funny thing about this is that your art was about to go through a transformation, staying spare but looking beautiful.

That one comic has caused me more headaches than any other. People still reference it and bring it up to me, but it’s embarrassing. As a point of view it’s not very complex, it doesn’t go very far. Maybe I felt that way for five minutes, or maybe I felt that way, but there were other sides of it I felt that I didn’t express at the time. Clearly there is beauty in the world, and clearly art that depicts that is not in some way fraudulent. But at the time I guess it was my way of saying where I came from. It was true for me at the time, but not true for everybody. And I was about to move on from that point of view pretty rapidly.

“Down The Toilet”: this is the crudest but funniest strip you reprinted in this issue, as you show your degree to be worthwhile only as toilet paper in the nastiest way possible. Do you still think the same way about your degree after all this time? What do you think about the new wave of pedagogy that you’ve been involved with sometimes, like at SAW (The Sequential Artists Workshop)? How do you think that might have affected your career if you had had something similar?

When I look back at my college years… I was an art major, my degree was in painting. I think you can teach people how to build a stretcher, how to mix paint, how to clean and fill a Rapidograph. But do I think you can teach someone how to be an artist? No. You can encourage and help a person to develop their individual artistic talents, but you’re either an artist or you aren’t. I mean you can be a person who is not an artist and then becomes one. Or vice versa. There are many people who were artists at one point in their lives and left it behind. By that I mean the sensibility. Being an artist is learning to look at the world through your own unique, incomparable eyes and then sharing what you find with others.

You don’t have to paint to be an artist. You can be a veterinarian or a plumber. If you bring artistry to that work, you’re an artist. We all know people like that. Some people have that artistic sensibility and bring form to comics, paintings, poems, some cut dogs’ toenails.

In college I felt like I was primarily on my own, and that’s how it should be. I had two teachers, I don’t want to say good teachers... because I had other teachers that were good, but I had two that were good but became something more to me. One was John Rooney, whom I mentioned previously. He helped me develop core skills and attitudes about what it means to work as an artist. Most of all he made me do a shitload of work in a short period of time. When you do a shitload of work in a short period of time you can’t help but learn some things.

When my relationship with Rooney soured, and my approach and attitude toward making art changed, I found my second mentor, Ben Mahmoud. Where Rooney maybe saw my talent and drive, Mahmoud saw my heart and mind. He got it. That second half of my college art career was one of self-destruction. I wanted to annihilate art, myself as a painter, myself as an artist. I had to destroy myself to find out what was left over afterwards. What was left over was my real self.

So when I talk about art school, am I talking about building a portfolio? No. I’m talking about doing seriously hard, deeply personal self-work, breaking down preconceptions, breaking down inherited attitudes, finding out what’s really inside you, and learning to bring that out in a holistic, autonomous, absolutely unique way. That’s the power of art, that’s how it changes lives.

Essentially, in terms of art education, I believe it can give you those three things: It can teach you fundamental, practical essentials, like color theory, design basics, foundational things that will be useful throughout your career. Two, it forces you to make a shitload of work in a short period of time. It prevents you from being lazy, it forces you to make progress. Lastly, if you’re lucky, you’ll meet one or two teachers, and one or or two friends, who will challenge your ways of thinking, whose lessons will stay with you as you move forward through life.

Ultimately, I prefer and endorse the SAW model, the workshop model. Especially for comics. Do you need to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to learn how to make a minicomic? Absolutely not. And the best way to learn comics is to make a minicomic, and then make another minicomic, and another and another and then keep going for decades. Just make comics. SAW and places like that provide a certain expertise, artists from whom you can learn by personal example. They also provide a community, so you’re not working in a vacuum (although working in a vacuum certainly works for plenty of people, too). And they get you working, trying things, failing, picking yourself up and getting going again. By peer pressure if nothing else. Some people can do those things on their own, some people might benefit from having help. But it all comes down to doing work and more work, and being thoughtful, and self-critical.

In #23, Racky Raccoon emerged as a fictional character who was more of a mouthpiece than any other fictional character you had created. This feels the most influenced by underground comics of anything you’ve ever done: angry, funny, punk.

Also, how did it affect your confidence to see this comic sold in a store?

I don’t know that it affected my confidence much, I was already selling King-Cat through the mail, I had my community of zine people, that audience, that was already very satisfying. The comic book store audience was something different. Maybe it felt little irrelevant to me at the time.

I used to stop in at Kurdworks Comics in St. Charles on my way between DeKalb and Hoffman Estates. Frank Kurtz was the manager. I’d buy Lloyd Llewellyn, Neat Stuff, etc there, and rummage through the quarter bins for odd, old comics. On his shelf he also had some self-published comics by Mark Cunningham, who later became Jenny Zervakis’s husband, and some scratchy ninja minicomics by a pre-teen kid. I thought, well I can sell King-Cat here no doubt. Frank was very supportive. Dan interviewed him for the movie. He got my foot into the door of the comic book store world. It was, and remains, a very odd world. I’m a lifelong cartoonist with multiple books out under my name, foreign language editions, TCJ interviews, and yet walking into the average comic book shop makes me feel like less than nothing. It’s that oppressive. The superhero crowd had and still has to a large extent not only a dismissive attitude to my kind of comics, but an open revulsion. So with Frank, it was a breath of fresh air.

Shortly thereafter you had the zine explosion happen, and shops were more open to stocking this kind of work. By that I mean mostly record shops, cool book shops. Quimby’s opened in Chicago. But even some comics shops were more open to it. If nothing else they’d sigh and say “sure,” and then stick your minicomic in a plastic bag behind the counter with the Cherry Poptarts.

Issue #25, the all-cats issue, had an especially upbeat feel to it. Did it make you happy to just tell stories about cats you had known? Was this an issue that came about relatively quickly?

I had probably dropped acid by that point, so yeah it was happier! You know, much of my work has been oppositional. That was part of what I got out of punk. It wasn’t as much the part about having a mohawk and slam dancing as it was the part about being yourself no matter what, defying expectations, “no rules.” So I was happy to be a punk that drew comics about loving cats, because that’s who I was.

Those early issues, they all came about quickly. I was just piling those finished pages up one after the other. I wasn’t hung up on what made a good story or not, or what made a good drawing or not. I learned as I went. And I was young, full of energy, and maybe enthusiasm is the wrong word, but definitely energy. I was creating from morning till night, and through the night -- paintings, poetry, playing in bands, making comics. It was very spontaneous. Knock something out and go on to the next thing without looking back too much.

“Another War Dream” in #26 hit close. You really captured what a lot of us around that age were feeling regarding the first Gulf War: confusion, fear, anger. America hadn’t been at war for fifteen years, which is hard to think about now. While this was a dream, how much were you worried about this on a day to day basis at the time?

I think about it sometimes. I grew up during the age of Nukes and AIDS. Life was threatening on a day to day basis. I was pretty young, in high school it was like, “Fuck it, I could be incinerated in the next second.” I was maybe too young to fully fathom what that meant, but there was an underlying existential angst or maybe meaningless to the world that we felt. You couldn’t get too excited about things, because you were always on the verge of atomic annihilation. This is where that “Well Drawn Funnies” attitude came from.

Then, with the Gulf War, memories of Vietnam were still pretty fresh. There was GOP horseshit like Grenada and that, but when Bush sent troops to Kuwait, it was like "fuck." This was fighter jets, tanks on the ground. It didn’t seem real, that the country that had learned the lessons of Vietnam was doing this?

Now of course you have a generation of Americans who have never known anything but perpetual warfare. I suppose it’s something that will continue at this point until the American Empire collapses. The military-industrial complex isn’t giving up those blood-soaked dollars anytime soon, and our politicians are either helpless to stop it or actively profiting from it.

“Today” in #26 almost feels like a response to diary comics where nothing happens; you just went about your boring work day in great detail. Were you demonstrating why you almost never did comics like this?

Ha ha, no, that’s a great comic! It’s funny. “Maybe I’ll draw some more fucking comics.” I think that strip captured some of the daily depression and boredom with life that I was feeling at the time. The day to day grind of working in a warehouse was beginning to wear me down. As a genre, diary comics didn’t exist yet. James Kochalka invented them in the '90s, or Delaine?

Anyhow I was always interested in comics where nothing happens. That’s was a big part of it for me. I wanted to not only show the exciting, emotional, thrilling, life changing moments, but the deadly dull, repetitive ones. Those are the moments that make a life. Putting on your shoes, eating oatmeal for breakfast every day for years on end.

What kind of reaction did the Racky story in #27 receive, the one where he becomes a Kirby monster and destroys the city? It was hilarious when he stopped and realized that he couldn’t beat the forces of capitalism simply by smashing them and he started ruminating on the culture at large.

What kind of reaction did the Racky story in #27 receive, the one where he becomes a Kirby monster and destroys the city? It was hilarious when he stopped and realized that he couldn’t beat the forces of capitalism simply by smashing them and he started ruminating on the culture at large.

It got a pretty good reaction from me! I liked it. But at the time, I’m not sure of the exact numbers, probably my print run was like thirty copies? So if there was a reaction at all it was a pretty modest one.

That was my homage to the comics I mentioned earlier, that I was picking up in the quarter bins at Kurdworks… the 1970s Marvel monster reprints, like Monsters on the Prowl, Where Monsters Dwell, etc. I’d find them in the bins and they were electric to me. Those beautiful covers leaped out at me. And the stories fulfilled every one of my ironic, ridiculous dreams of the time. They were all the same -- repetition! Misunderstood scientist is scorned by the woman he loves, monster appears, scientist saves the day, and finally receives the love and admiration of the woman that he deserved all along. That was very appealing to me. And funny, and goofy. Those comics are nuts. You could tell they were made up as they went along, in the best way. That’s what “comic books” are to me. Corny, beautiful, nutty, American. It was only later that I realized these were stories by the comic book greats, Kirby, Ditko, Don Heck, Bill Everett. It’s no wonder they were instantly appealing to me. They were by master cartoonists at the height of their powers.

Issues #29 and #30 feel like the big transition issues. You had the first King-Cat Snornose (an introductory section) to further draw in readers and share your life with them. You wrapped up "Violent Garden" and had an increasingly rare sex dream in #29, and a long essay about the cover which was quite moving.

“October” is the first story where I could really start the see the influence of Zen in your life, even before you started studying it. It’s a carefully considered piece of a normal day that is capped by that astonishing page where it’s just the night sky, and you are awed in the face of eternity. It’s a fitting end to the first volume, a kind of paradigm shift. When you wrote that story, did you have a sense that you were about to go in a different direction, or was it just natural for that moment for some reason?

“October” is the first story where I could really start the see the influence of Zen in your life, even before you started studying it. It’s a carefully considered piece of a normal day that is capped by that astonishing page where it’s just the night sky, and you are awed in the face of eternity. It’s a fitting end to the first volume, a kind of paradigm shift. When you wrote that story, did you have a sense that you were about to go in a different direction, or was it just natural for that moment for some reason?

Yeah, I knew right away I was onto something different. There were tidbits, hints of that feeling in earlier stories, but “October” was the first one where it came to full fruition. I remember as I drew it, the feelings in me rose, until that last panel felt like such a release. I didn’t really write out my comics beforehand at the time, like I do now. I just had a kernel of an idea, or a bit of dialogue or line of text, that I knew I’d wrap the story around, and I’d kind of jump into the page without really knowing where I was going to end up. With October I ended up someplace that felt very special to me. It was an artistic feeling I knew instantly I wanted to pursue further. I don’t want to take the magic away from it, but it’s pretty obvious. It’s that moment where the massive inexpressible overarching perfection and mystery of the universe breaks through into apprehension in our everyday, mundane lives. Right away I knew this was it -- this is what I was looking for, what I had been pursuing my whole life. I couldn’t put it into words like that at the time, it was too new. But it was a moment of self-understanding for me. It gave me a new direction and a bit of a new focus.

"Volume 2”: 31-50

In issue #31, “Ed” is a classic work story, but it’s almost as much in the style as Harvey Pekar as it is yours. Was American Splendor a comic you had seen at this point?

Right when I started King-Cat a number of people told me, “Wow, you have to read American Splendor!” And because of that I intentionally stayed away from reading Pekar’s stuff. I didn’t want what he was doing to “taint” my work. Was there any Pekar stuff in Weirdo? If so I probably read some there, but no actual issues of American Splendor. It wasn’t till after my surgery in ‘97 -- on the way home from the hospital we stopped at All in a Dream on Colfax and I bought a stack of comics -- like $75 worth! To give you an idea of how things have changed, $75 worth of comics and trade paperbacks back then was like a stack two feet high. In that stack was Our Cancer Year. I read it on our couch and I already knew I would write the Hospital Suite book someday and I was like, “Damn! Pekar beat me to it!”

“Madonna and Me” in #32 seems a perfect blend of Volume 1 silliness and Volume 2 craft. Had you read any old-style romance comics for inspiration?

Yes, well it was those quarter bins! I dug through them for anything weird looking or absurd or ridiculous. Of which in the world of comics, there is plenty. So I had read some romance comics by that time. During my early high school years I didn’t really read comic books. But my friend Fred got into Marvel comics, and I would go with him to Moondog’s on New Comics Day. There was a period of maybe six months or a year where I read superhero comics. Even then I knew they were corny. Me reading them it was somewhat of an ironic act. To me superhero comics were like something -- like Joey Ramone might have a copy of a Spider-Man comic rolled up in his back pocket. It was low class and corny and dumb. But I got into them for a bit. This was when like Web of Spider-Man came out, Secret Wars II. I read Fantastic Four, The Punisher, Daredevil -- "Born Again" was during this time. At some point, it was an FF comic I remember and I was like “This is a soap opera. They just hook you in and make you feel like you have to read the next one.” And they were dumb. Like the Fantastic Four goes out and has this big dangerous adventure and when all seems to be lost, Reed makes some dumb machine in five minutes that doesn’t make any sense but saves the day… I just stopped buying them.

Luckily this was the golden age of comic book shops, so when I quit reading superhero stuff there were a couple dozen other options for me on the shelves -- and I started reading Neil the Horse, Lloyd Llewellyn, anything oddball that was coming out instead. Right away I knew this was the stuff I was really into. And so that’s about when I started digging in bins for older comics that gave me the same mad rush… Night Nurse, Brother Voodoo, Kirby monster comics, old romance comics, Hot Stuff. Five for a dollar, my friend!

I should say, the stupidity of superhero comics I mentioned above -- to me, now, in 2018, that’s what I love about them. Especially the classic stuff. I can read Kirby FFs from the '60s and I absolutely love them. They’re just anything goes, and the art is great, and it’s kind of campy but also kind of really awesome. When it comes to superhero comics, I realized I’m into the artist more than I am the character. If it’s by Kirby, bring it on, I want to read it. Or Bill Everett, or Ditko up to a point. But I couldn’t care less about Batman as a person.

In issues #33 and 34, respectively, “Freaks” and “Muskrat Love” seem like quintessential John P stories that I could easily see appearing in a contemporary issue. As a cartoonist, how do you work on conveying empathy for the subjects of your strips? You have a knack for showing the humanity of everyone involved in a situation and understanding their reactions to things. Same goes for “Moon River” in #36.

I just try to depict people in a straightforward way. People are human. Just show them as people, and that humanity comes through. Maybe there’s a touch of a smile to it, sometimes a wry smile, but a smile nonetheless. The master of this is Kelly Froh. She can write about the most monstrous people, doing the worst stuff, and yet you come away with a sort of affection for them, for their humanity. I don’t know if there’s a way to bottle that. It maybe comes out of the artist’s own soul. I have affection for people. It’s that absurdity that unites us. We’re a bunch of desperate sentient animals spinning on a rock in space. It’s ridiculous. Fundamentally, we’re all in the same boat.

In #36, “Leaves” is an all-time favorite of mine and one of your best nature poem-comics. Have you ever considered doing a collection of just your nature comics and/or just your poetry comics?

I think when I first started working with D+Q there was discussion about doing something like that, or maybe it was even in the Highwater days. Like doing a book of music stories, a book of nature stories, family stories. I don’t know. That starts to get into the gift book mentality. “My grandma likes dogs, so I’ll buy this King-Cat Dog Book for her…” It’s just not my scene. Plus, to me, a big part of what I’m aiming for with King-Cat is all these stories are thrown into the same big stew with each other. There’s an angry punk comic, a comic about cats, about how I love my ma, about Herb Alpert. It’s all part of the same thing. Then again, we did it with the Mosquito book and it was fine. But that’s almost something else too, that’s a distinct category of work within King-Cat… almost a narrative in itself. Like maybe you could print a book of all the "Violent Gardens", or all the "Trail Watch" strips, and that would hold together. But I’m happy with how we’re doing things now.

I usually show “Leaves” in my workshops, and talk about it. I didn’t realize it at the time, but looking back I saw -- this was one of my first comics where not only was it about nothing happening, it was about even less than nothing happening... it was instead about the feeling of nothing happening. It was about a frame of mind within which life is transpiring before us. That was a turning point for me, too, a new direction to go in. Paring things down to essentials, and what is more essential than mind, consciousness?

In #37's “October Part 2”, I was always surprised that you didn’t do more comics about being in a band, since it seems like such a natural story-generator. Was there a reason why you stayed away from doing that?

I had this weird thing where I kept my band life and my comics life separate. I mean, people who knew I was in a band probably knew I was making comics, but for some reason I kept them separate. “October Pt 2” is drawn years after the fact, so it’s less about writing “I’m in a band” than it is “I was in a band once, here are some memories of that.”

One of my big projects I’m working on now, that I pulled out after like a decade of gestation, is a history of one of my bands, Smile, who were around from like ‘89-’91. It was my first band that like started touring, and it was at the dawn of the grunge phenomenon, when underground music changed, seemingly overnight. So besides having like tons of funny tour stories, it’s got this undercurrent of here’s this remarkable scene, and here’s how fast things went bad once ego and money and competitiveness crept into it and replaced community. So there’s a couple conceptual strands running through it. I kinda kept waiting to pull it out again until Raina [Telgemeier]’s Smile dropped off the New York Times bestseller lists, but that’s probably going to never happen, so I’m just gonna do it. I’ve just started interviewing people for it again. I’m looking forward to making that book.

“Sam” in #38 is another personal favorite and the spiritual ancestor of the all-Maisie issue in #75. This was also one of your longer narratives. Did you have a sense in putting it together that you had done something special? The way you tie Sam into various stages of your life was especially affecting, in particular the teenage years.

As for being special, I mean I knew it was affecting -- drawing it was affecting to me. Something like that, it almost can’t help but move people to tears. It’s a boy and his dog, growing up, losing his innocence, drifting apart, coming back together.

The "All Sam Issue" was a milestone for me too, in terms of expanding my readership. Adrian Tomine had made a huge splash with his Optic Nerve zine, and he threw a plug in there for me, for the "All Sam Issue." I got a boatload of orders and subscriptions from that one plug. It was a noticeable difference. That’s how things worked in the '90s.

It’s funny that your first Maisie comic (in #39) was a dream comic. Had Maisie become that big a part of your life that quickly?