“Moving pictures are a ticket of admission to other worlds.” —Richard Temple

Clearly Jack Kirby was a man lost in dreams. Mort Meskin was a man of dreams as well, although by most accounts those of a darker nature. Having just returned from what was euphemistically referred to as a rest home, he was persona non-grata at his former employee National/DC, due to missed deadlines and erratic behavior. In 1949 the Simon and Kirby Studio were going full steam ahead, supplying complete stories to several comic publishers, and in need of someone with Meskin’s artistic abilities and known speed to lend a hand. Kirby and Meskin had worked side by side previously, first at the Eisner/Iger Studio in 1938 and later at National briefly in 1942, before Kirby was drafted into the army. Meskin even lent a brief hand on Captain America #3, providing partial inks for one 1941.

However, up to this point, these early comics masters had never truly collaborated. That was about to change. Simon and Kirby’s most recent success was the invention of Romance comics aimed at teenage girls, a previously untapped market, and they were creating comics across myriad genres: kid gangs (another S&K creation), Westerns, crime, war, horror, occult, and superhero. One prime example of collaboration between Kirby and Meskin was a failed attempt at a current craze: Captain 3D (“Thru Space! Thru Time and into the Third Dimension…!”) Published by Harvey in 1953, issue number one featured pencils by Kirby with inks by Meskin and assistant Steve Ditko. Work had begun on the second issue when word came down that the title was canceled and work was to be ceased. However, one story was completed in pencil by Meskin. What is of particular interest is that the handwriting in the balloons and captions is clearly Kirby’s; the only logical conclusion is that the story was written by Jack, one of the few existing clear examples of Meskin working from a Kirby script. Less certain is whether Meskin was working over loose layouts by Kirby as well, something Kirby did later at Marvel when he was plotting a story for other artists to render.

Another close alliance between these two was Boy’s Ranch, for which Meskin seamlessly took over the penciling chores from Kirby within issue # 3, February 1951, for the 6-page “I'll Fight You For Lucy”, as well as supplying one- and two-page fillers and inks over Kirby throughout the six issue run. But their collaboration would reach a zenith that same year with the studio's oddest title to date, Strange World of Your Dreams. According to both Simon1 and Kirby2, Meskin, who reportedly was in Reichian therapy, would regale the studio with stories of his dreams and suggested the title. Issue number one was published on August 1952, with Meskin listed as associate editor on the opening splash--the only time someone other than Simon or Kirby was granted such a credit on their books.3

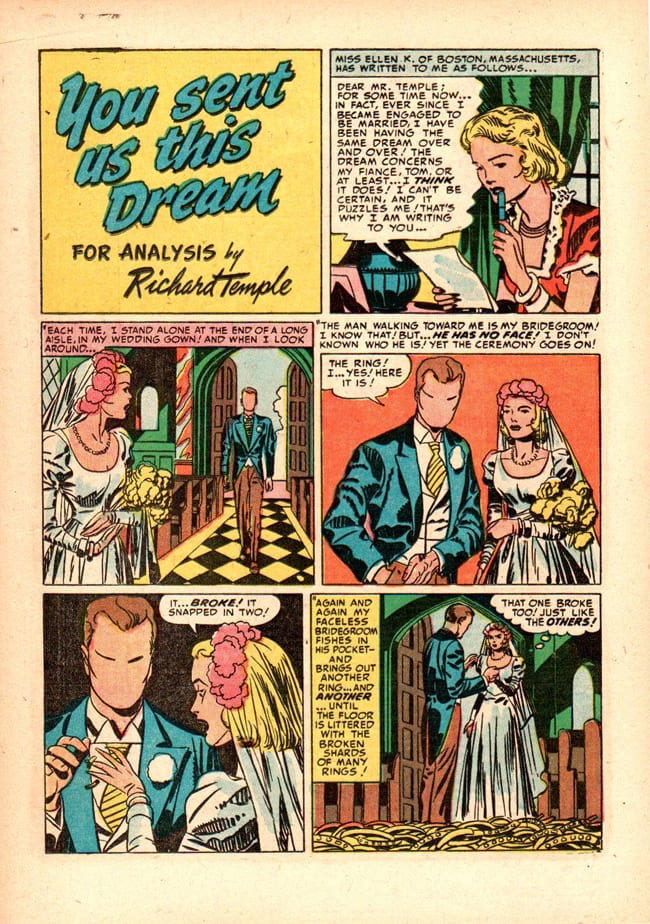

Boldly marked as “True” in the top left panel, it featured some of the same contrivances as the Simon and Kirby romance titles, such as the column “You Sent Us This Dream,” “written” by fictional dream therapist Richard Temple, who interpreted dreams sent in by readers; an unlikely possibility, since no solicitation for such ever appeared anywhere prior to publication. One notice that did appear in this first issue promised $25 for every dream that would be selected for publication. One wonders how many checks were actually written over the four-issue run. Temple also serves as host throughout most of the book, even in the all text single pagers, which guaranteed the title “magazine” status for postal purposes.

The first story in the premier issue “I Talked With My Dead Wife!,” is a tale of an overwrought father of a dying girl who is visited by his deceased wife in his dreams. Laying the foundation for all that is to come, Simon, Kirby and Meskin’s approach to the subconscious is more related to the popular radio show “Inner Sanctum” than Freudian theory. Perhaps this was a missed opportunity, as Kirby and Meskin could have explored new vistas visually had they afforded themselves the freedom to do so. Still, these were comic books intended for a mass audience, and they stuck fairly close to the story telling formula and visuals of their other occult titles, such as Black Magic. However the content is surprisingly adult in nature and they make the most out of the material considering the context.

The dream “sent in” by Julie Pendelton, age 18, featured some beautifully clean line-work by Kirby in a style he would continue with going forward, and the writing has many of the hallmarks of his staccato prose as well (“It was strange! Unexpected! Humiliating! I couldn’t understand why my feats of balance and agility did not impress them! The laughter rose to a loud and cruel pitch!”) In the true shared spirit of the endeavor, the portrait of Temple that opens the piece is by Meskin, not Kirby. The precision of the art stands in stark contrast to the one that follows, “The Dreaming Tower” by Meskin.

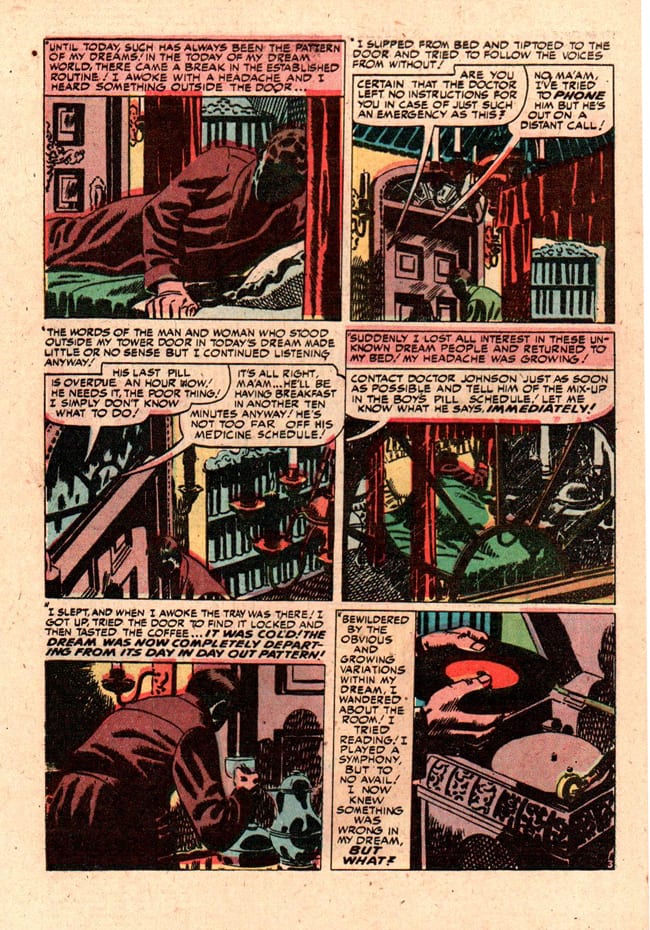

Here we never view the face of the protagonist, steeped in moody shadows and crosshatching, until the great reveal. Meskin’s cruder approach is at once overwrought and evocative. Unfortunately, and this may be a personal bias, when the art chores were turned over to others, including Simon and Kirby regulars Bill Draut and Bill McCarty for more than a quarter of the run, much of the power of the stories was lost.

With the second issue some caution set in in the form of a typeset disclaimer on the splash page, perhaps the result of legal counsel: “The Advice which Mr. Temple offers in this story is intended for the person involved and applies to that individual’s situation—a similar dream could have a completely different interpretation for someone else.” And rather than any implication of medical training, Temple is now referred to as the “Dream Detective.”

One wonders how close at hand Simon, Kirby and Meskin were keeping a standard dream interpretation encyclopedia at hand (a tombstone with one’s name = doubt; candles = key to the solution; water representing the subconscious; etc). And much of the material seems dated. Still, there is a great deal here that is unexpected, and you get the sense all involved enjoyed creating the material. And in contrast to the popular belief of post-war prosperity and ideality, the comics exhibited the very real worries of self-doubt, the threat of war and the atom bomb, even ulcers. By couching their concerns in the dream world, the creators were able to comment on the headlines of the day in an oblique way not afforded them by any other genre. Perhaps the post-war drop off in comic book sales and the burgeoning movement against comics for inducing juvenile delinquency were beginning to hit home. Indeed, with so many stories revolving around job insecurity, one wonders exactly how personal these fears were.

The subject matter also afforded them the opportunity to survey several existing genres within these pages: romance, the battlefield, sci-fi, colonial America (a Meskin trope). Oddly, a horoscope is introduced as a “special featurette (sic)” although the relationship between the world of dreams and astrology is nebulous at best; perhaps it was a subject borrowed from the magazines of the day intended for teenage girls.

Strange World of Your Dreams was indeed a unique book. It wasn't genre, had great potential and afforded Simon, Kirby and Meskin the opportunity to create stories for adults at a time when comics were still viewed as kiddy fare. Strange World of Your Dreams only lasted only four issues. Like many other titles at the time, it simply didn’t have legs. Perhaps it simply was too exoteric for the prevailing market or ahead of its time. However, it stands as one of the more ambitious and adult projects of the early years of comic books.

Footnotes:

- http://simonandkirby.blogspot.com/2006/04/mort-meskin-usual-suspect-2.html (Harry Mendryk)

- Jack Magic Vol. I, The Life and Art of Jack Kirby by Greg Theakston, 2011.

- http://kirbymuseum.org/blogs/simonandkirby/archives/210 (Harry Mendryk)